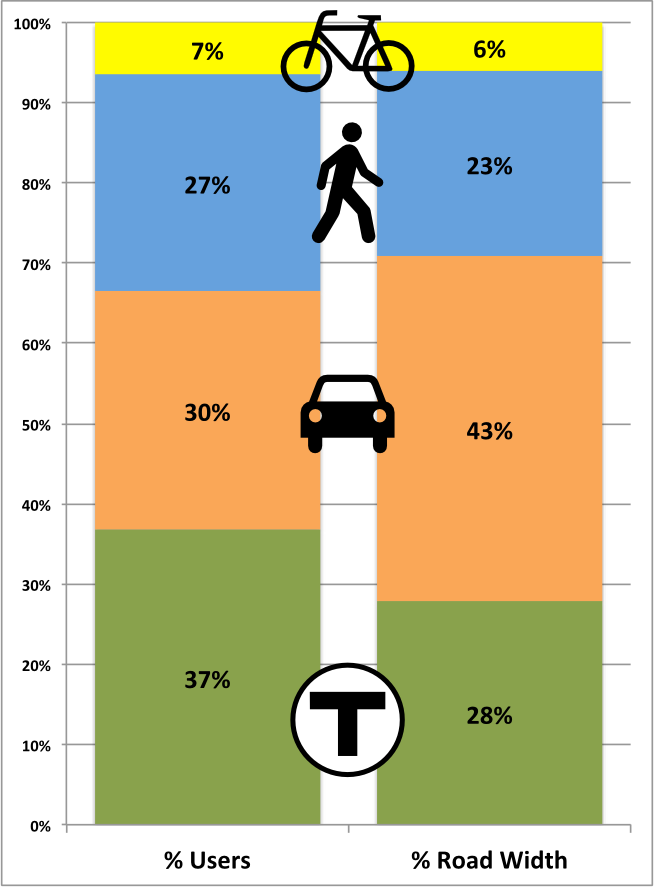

We’ve been covering Commonwealth Avenue a lot recently on this page, and here’s another post (likely not the last). In the last couple of days we’ve seen the Boston Globe editorialize that the current design is subpar, which, despite the supposed end of print media, is a decently big deal. This post will be somewhat short on words, but I think get across an important point: the current design gives drivers more room than they deserve, and gives the short shrift to everyone else: transit users, bicyclists and pedestrians. Many thanks to TransitMatters for digging through the BU transportation plan (several hundred pages, including the entire MBTA Blue Book appended to the end) and finding their peak hour traffic counts. He presented it as a table, I simplified it a bit (grouping all transit riders) and show it to the right.

Tag Archives: bike

The next step on the BU Bridge area for bikes

The City of Boston recently made somewhat dramatic improvements to the bicycle facilities along Commonwealth Avenue. The formerly orphaned bike lane has been restriped through the intersection, and the new paint is all bright green. In addition, there are reflectors in the road to the right of the lane which I can attest are very visible from a vehicle at night. It’s a good start.

Meanwhile, Brookline has installed contraflow bike lanes on Essex Street to allow cyclists to go from Essex to Ivy to Carlton and allow a low-traffic alternative to get from the BU Bridge to the Longwood area. (And for those of us headed to Coolidge Corner, another block before we take a right.) Going towards the bridge, the town has striped in a bike lane. And, more importantly, they’ve cut a “bicycle crosswalk” across the BU Bridge loop (Mountfort Street) to allow cyclists to get from the Brookline streets to the BU Bridge without having to cross medians, loop around through the intersection of death, or ride the sidewalk to the light. It also allows cyclists coming from Brookline to skip Commonwealth altogether, a great boon to cyclists who don’t want to ride one of Boston’s widest and busiest streets. So, what was once a death trap for cyclists—and is still rather cumbersome—is getting better. (The picture at right shows the bike lane in the foreground and the crossover in the background.) There is some background information in this document.

The next step, I think, is to better allow cyclists coming from the west on Commonwealth and headed towards Cambridge, would be a two-stage bike turn box. This is not a new concept—it even exists in Boston—and goes as follows:

- An eastbound cyclist on Commonwealth approaches the BU Bridge.

- The cyclists, upon a green light, goes through the light, then pulls in to a separate line to the right of the bike lane and turns their bike towards the bridge.

- Once the light changes, the cyclist pedals straight across and in to the bike lane on the bridge.

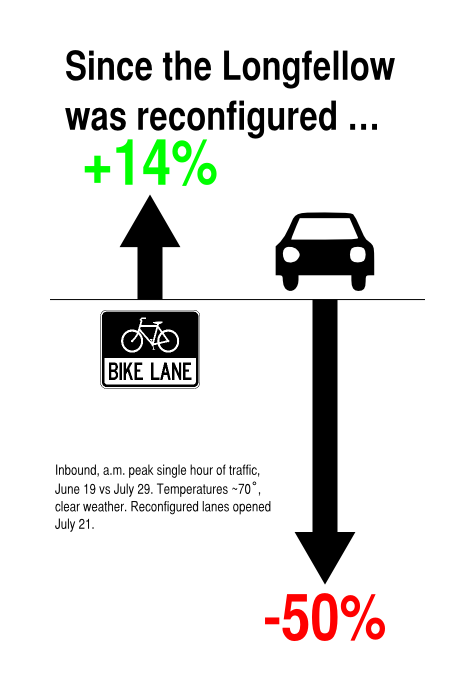

One chart shows the change in Longfellow traffic

Boston’s massive reconstruction of the Longfellow Bridge

began this month. Over the next three years, traffic will be severely

restricted, bicyclists mostly accommodated, and rail traffic mostly maintained

across a major link in the transportation system which carries 100,000 transit

riders as well as several thousand bicyclists and pedestrians across the

Charles River (and some vehicular traffic, too).

morning, inbound traffic across the bridge. With the new traffic configuration

in place (an inbound bike lane, a travel lane, a pylon-lined buffer and an

outbound bike lane, plus the sidewalk) I decided to take a new snapshot of the

bridge traffic. Had traffic declined with fewer lanes available? Are cyclists

shying away from the new configuration?

overall, and the peak hour saw 308 cyclists, an increase 14%). Vehicle counts, however, showed a dramatic drop, declining by 50% from 840 to 400 during the peak hour of use! It’s interesting that this is

not due, necessarily, to restricted capacity (the one lane of traffic didn’t

back up beyond the midpoint of the bridge at any time when I was counting,

although the afternoon is a different story) but perhaps the perception of

traffic, and the fact that the single lane reduces traffic speed quite a bit.

iteration of the Longfellow traffic pattern. The bicycle facilities are, if

anything, improved over the bridge before, especially considering the much lower vehicular traffic speeds and

volume. And there is no lack of cyclists—even on one of the quietest weeks for

traffic midsummer, there were more bikes than a day with similar weather in

June.

- Bicyclists and Pedestrians accounted for 60% of the traffic on the bridge. Cars transported fewer people than human power. (See diagram below.)

- Between 8:30 and 8:45, there were actually more bicyclists

crossing the bridge than vehicles. - Pedestrians of all types outnumber cyclists (although this

includes both joggers and “commuters”—as defined by me—in both directions). - The flow of “commuting” pedestrians is a mirror image of

bicyclists. There are four times as many Boston-bound cyclists as

Cambridge-bound, but more than twice as many Cambridge-bound Pedestrians as

Boston-bound. (There are fewer joggers, but they exhibit a preference towards

running eastbound across the bridge, differing from the other foot traffic.) Overall there are more bicyclists going towards Boston and more pedestrians towards Cambridge. - While 24 Hubway shared bikes accounted for only 5% of

inbound bicycle trips, the 20 outbound Hubways made up 18% of the

Cambridge-bound bicyclists. - Only four cyclists used the sidewalk, and only one rode the wrong way in the contraflow lane. (I yelled at him.)

Personal data collection: Hubway

Back in 2011, as part of a convoluted New Year’s resolution, I started tracking my personal travel daily. Each day, I record how many miles I travel, by what mode, and whether I am traveling for transportation or exercise/pleasure. Why did I start collecting these data? Because I figured that there was the chance that some day it would be useful.

And that day is … today!

I realized recently that I had a pretty good comparative data set between the April to July portion of 2012 and 2013. Not too much in my life changed in that time frame. Most days I woke up, went to work, came home and went for a run. Probably the biggest difference, transportation-wise, was that in 2012 there were no Hubway stations in Cambridge, and in 2013 there were. In addition, since Hubway keeps track of every trip, I can pretty easily see how many trips I take, and how many days I use each mode.

To the spreadsheets!

The question I want to test is, essentially, does the presence of bike sharing cause me to walk and bike more frequently, less frequently or about the same? Also, do I travel more miles, fewer or about the same? A few notes on the data. First, I am using April 6 (my first Hubway ride in 2012) to July 9 (in 2012 I had a bike accident on the 10th and my travel habits changed; Hubway launched in Cambridge at the end of the month, anyway). Second, I collect these data in 0.5 mile increments, and I don’t log each and every trip (maybe next year) but it’s a pretty good snapshot.

The results? With Hubway available, I ride somewhat more mileage, but bicycle significantly more often. In addition, my transit use has declined (but I generally use transit at peak times, so it takes strain off the system) and I walk about the same amount.

Here are the data in a bit more detail for the 95 days between April 6 and July 9, inclusive:

Foot travel. In 2012 I walked 84 days in the period a total of 190.5 miles. In 2013, the numbers 83/180. (Note that I do not tally very short distances in these data.)

Bicycle travel. In 2012, I biked 66 and, believe it or not, in 2013 I actually biked fewer days, only 64. As for the distance traveled, I biked 466.5 miles in 2012, and 544.5 miles in 2013. So despite riding slightly fewer, I biked nearly 20% more distance. This can be partially explained by my participation in 30 Days of Biking in 2012, when I took many short trips in April.

In addition, in 2013 I began keeping track of my non bike-share cycling trips. I only rode my own bike 14 days during the period, tallying 44 trips on those days. But there were many days where I rode my own bike and a Hubway; I took 29 Hubway trips on days I rode my own bike; on 8 of the days I rode my own bike, I rode a Hubway as well.

Bike share trips. In 2012 I rode Hubway on 39 days, totaling 71 rides, an average of 1.8 Hubway rides per day riding Hubway. In 2013, I rode Hubway on 58 days, but tallied 185 rides, an average of 3.2! So having Hubway nearby means that I ride it more days, and more often on the days I ride.

Transit. In 2012, I took transit almost as frequently as bicycling, 61 days. I frequently rode the Red Line to Charles Circle and rode Hubway from there to my office. In 2013, my transit use dropped by nearly half, to just 31 days, as I could make the commute by Hubway the whole way without having to worry about evening showers or carrying a lock.

We might look for the mode shift here. My walking mode shift has not changed dramatically. My bicycling mode shift hasn’t appreciably increased, although the number of total rides likely has. My transit mode shift has decreased, as I shift shorter transit rides to Hubway.

Now, if they ever put a station near my house, I’ll get to see how those data would stack up. My hypothesis: I’d never walk anywhere, ever.

Longfellow Bike Count

One of the issues I’ve touched on in the Longfellow Bridge series is the fact that there as no bicycle count done at peak use times—inbound in the morning. The state’s report from 2011 (PDF) counted bicyclists in the evening, and shows only about 100 cyclists crossing the bridge in two hours. Anecdotally, I know it’s way more than that. At peak times, when 10 to 20 cyclists jam up the bike lane at each light cycle, it means that 250 to 500 or more cyclists are crossing the bridge each hour. So these numbers, and bridge plans based on them, make me angry.

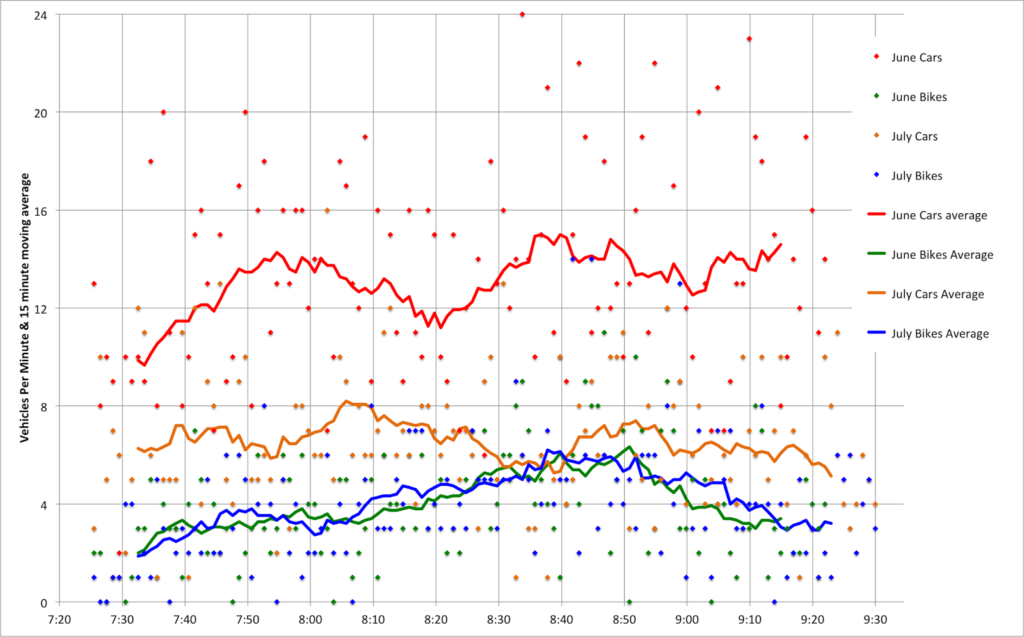

But instead of getting mad, I got even. I did my own guerrilla traffic count. On Wednesday morning, when it was about 60 degrees and sunny, I went out with a computer, six hours of battery life and an Excel spreadsheet and started entering data. For every vehicle or person—bike, train, pedestrian and car—I typed a key, created a timestamp, and got 2250 data points from 7:20 to 9:20 a.m. Why 7:20 to 9:20? Because I got there at 7:20 and wanted two hours of data. Pay me to do this and you’ll get less arbitrary times.

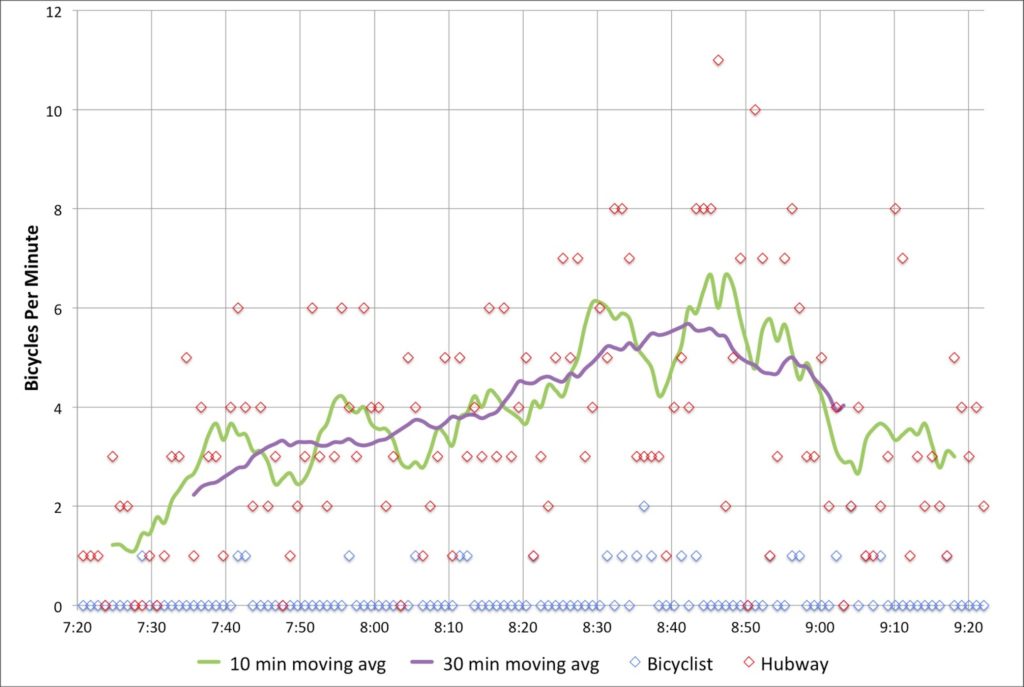

But I think it’s good data! First of all, the bikes. In two hours of counting, I counted 463 bicyclists crossing the Longfellow Bridge. That’s right, counting just inbound bicyclists, I saw more cyclists cross the Longfellow in one direction than any MassDOT survey saw in both directions. The peak single hour for cyclists was from 8:12 to 9:12, during which time 267 cyclists crossed the bridge—an average of one every 13.4 seconds. So, yes, cyclists have been undercounted in official counts.

Are we Market Street in San Francisco? Not yet. Of course, Market Street—also with transit in the center—is closed to cars. [Edit: Market Street is partially closed to private vehicles, with plans being discussed for further closures.] And at the bottom of a hill, it’s a catchment zone for pretty much everyone coming out of the heights. They measured 1000 bikes in an hour (with a digital sensor, wow!), but that was on Bike to Work Day; recent data show somewhat fewer cyclists (but still a lot).

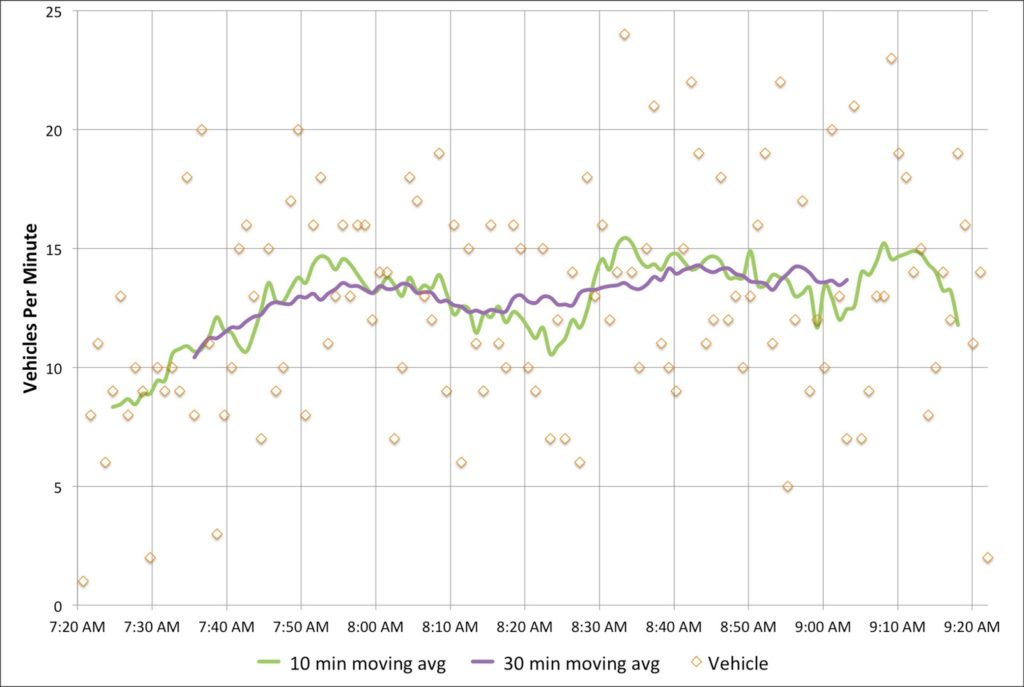

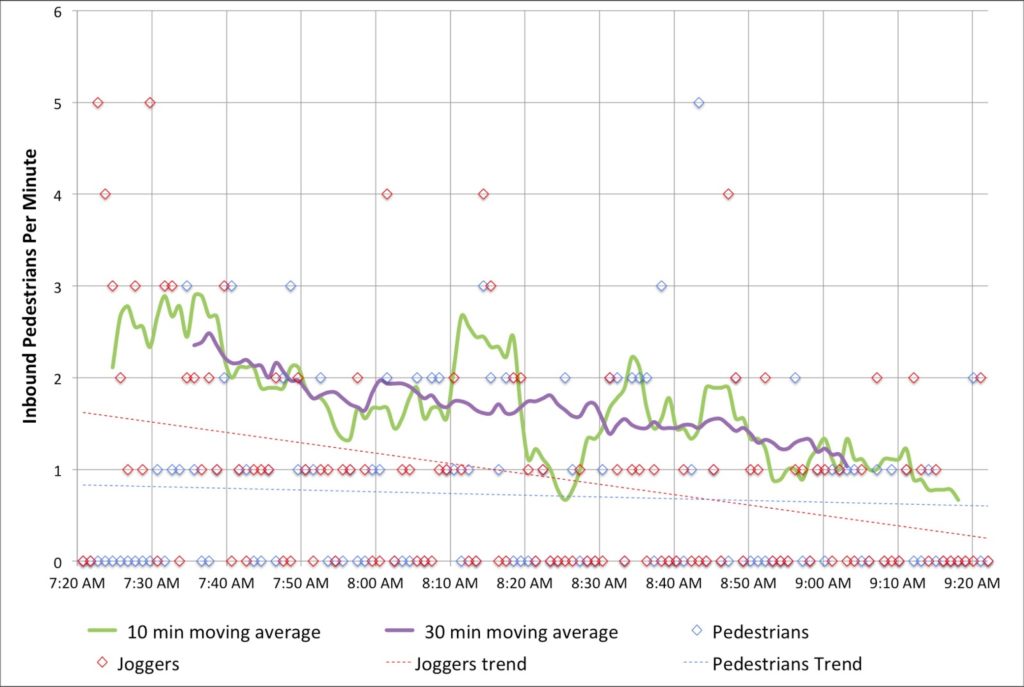

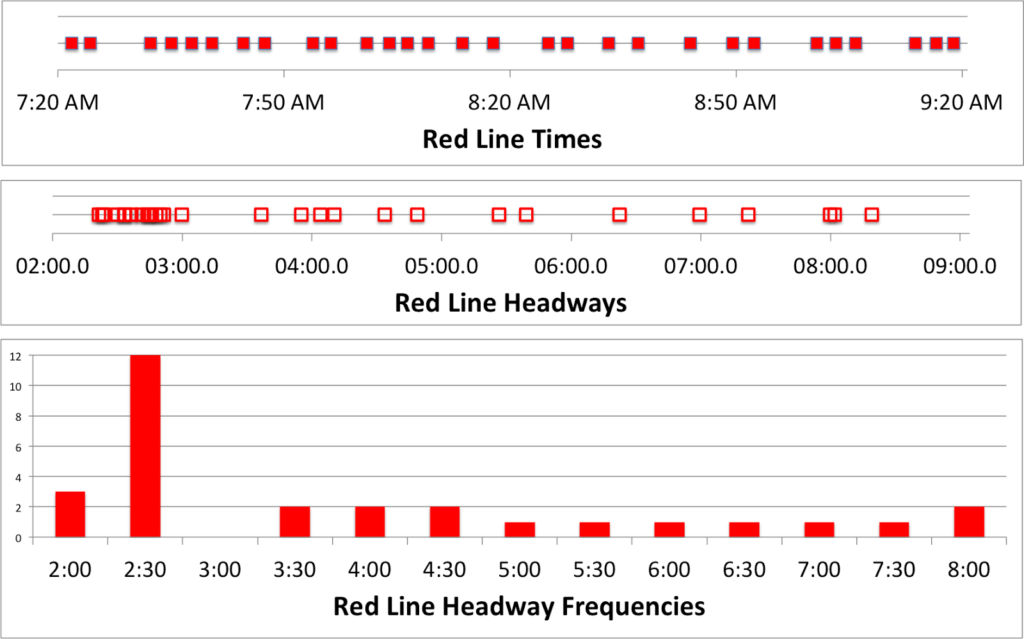

I also counted vehicles (1555 over two hours; 700 to 800 per hour, including three State Troopers and one VW with ribbons attached that passed by twice), inbound pedestrians (about 100, evenly split between joggers and walkers, although there were more joggers early on; I guess people had to get home, shower and go to work) and even inbound Red Line trains (30, with an average headway of 4:10 and a standard deviation of 1:50). I didn’t count outbound pedestrians, or the exact number of people I saw stopping to take pictures (at least three on my little nook of the bridge).

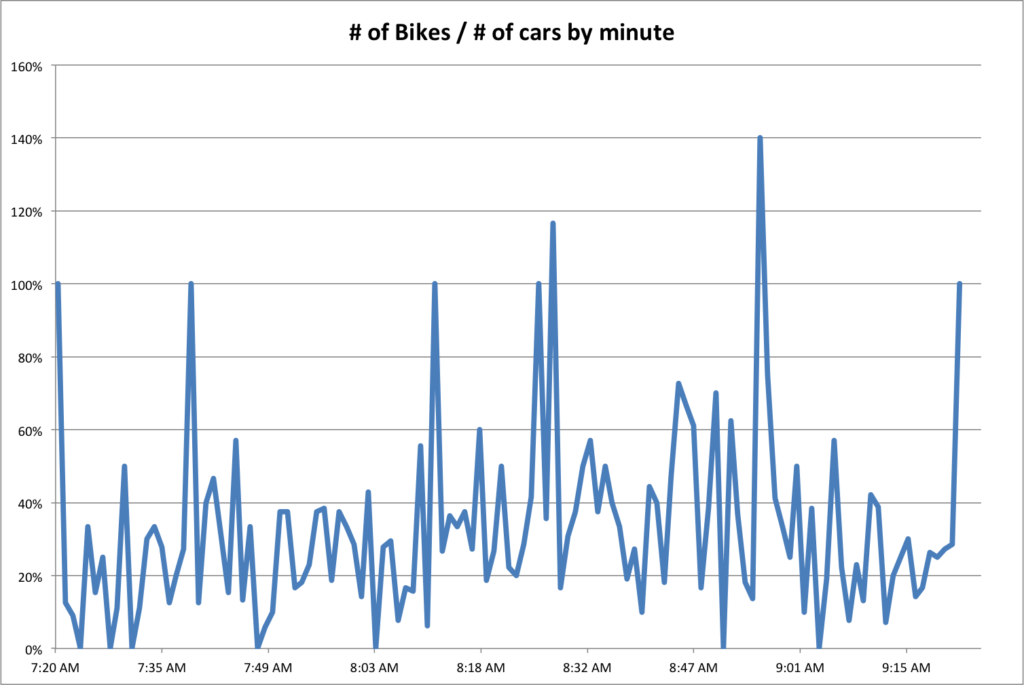

But did you come here for boring paragraphs? No, you came for charts! Yay charts! (Also, yay blogging at 11:20 p.m. when I should be fast asleep. Click to enlarge.)

First, bikes. Cyclists crossing the bridge started out somewhat slow—the moving average for the first 20 minutes was only one or two per minute. But the number of cyclists peaks around 8:40—people going in to the city for a 9:00 start—before tapering off after 9. I’ve written before about seeing up to 18 people in line at Charles Circle which is backed up by these data; the highest single minute saw 11 cyclists, and there were four consecutive minutes during which 36 bikes passed. At nearly 6 bikes per minute for the highest half hour, it equates to nearly 360 bikes per hour—or 10 per 100 second light cycle. Too bad we’re all squeezed in to that one little lane. (Oh, here’s a proposal to fix that.) If anything, these numbers might be low—the roads were still damp from the overnight rain early this morning.

What was interesting is how few Hubway bikes made it across the bridge—only 25, or about 6% of the total. With stations in Cambridge and Somerville, it seems like there is a large untapped market for Hubway commuters to come across the bridge. There are certainly enough bikes in Kendall for a small army to take in to town.

Next, cars. The official Longfellow traffic counts show about 700 cars per hour, which is right about what my data show. What’s interesting is that there are two peaks. One is right around 8:00, and a second is between 8:30 and 9:00. I wonder if this would smooth out over time, or if there is a pronounced difference in the vehicular use of the bridge during these times. In any case, 700 vehicles per minute is not enough that it would fill two lanes even to the top of the bridge, so the second lane—at this time of day, anyway—is not necessary on the Cambridge side.

I also tracked foot traffic. I did my best to discern joggers and runners from commuters. Joggers started out strong early, but dwindled in number, while commuters—in ties and with backpacks and briefcases—came by about once every minute. I was only counting inbound pedestrians, and there were assuredly more going out to Kendall. Additionally, I was on the subpar, very-narrow sidewalked side; the downstream sidewalk is twice the width (although both will be widened as part of the bridge reconstruction).

And I counted when the trains came by. In the time that 2500 bikes, pedestrians and cars crossed the bridge, 30 trains also did. Of course, these were each carrying 500 to 1200 people, so they probably accounted for 25,000 people across the bridge, ten times what the rest of the bridge carried. Efficiency! The train times are interesting. The average headway is 4:10, with a standard deviation of 1:58. However, about half of the headways are clustered between 2 and 3 minutes. That’s good! The problem is that the rest are spread out, anywhere from 3:30 to 8:30! Sixteen trains came between 7:20 and 8:20, but only 14 during the busier 8:20 to 9:20 timeframe. I wonder if this is due to crowding, or just due to poor dispatch—or a combination of both.

In any case, what Red Line commuter hasn’t inexplicably sat on a stationary train climbing the Longfellow out of Kendall? Well, after watching for two hours, I have an answer for why this happens! It is—uh—I was lying. I have no idea. But I say no fewer than a half dozen trains sit at that signal—and not only when there was a train just ahead—for a few seconds or even a couple infuriating minutes. I was glad I wasn’t aboard.

Finally, we can compare the number of bikes as a percentage of the number of cars crossing the bridge each minute. Overall, there were 30% as many bikes as cars. But seven minutes out of the two hours, there were more bikes across the bridge than vehicles. Cars—due to the traffic lights—tend to come in waves, so there’s more volatility. Although bikes travel in packs, too. Anyway, this doesn’t tell us much, it’s just a bunch of lines. But it’s fun.

Is a part-time bike lane appropriate for the Longfellow?

So far in our irregular series on the Longfellow Bridge we’ve looked at the difficulty accessing the bridge from the south, the usage of the bridge compared to the real estate for each use and how many bikes are actually using the bridge at morning rush. While my next step is to actually go out and count bikes (maybe this Thursday!), I’ve been thinking about what sort of better inbound bicycle infrastructure could be implemented for the bridge.

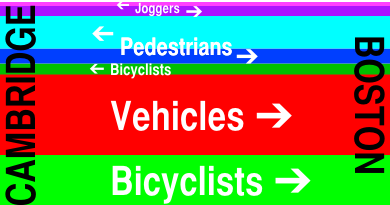

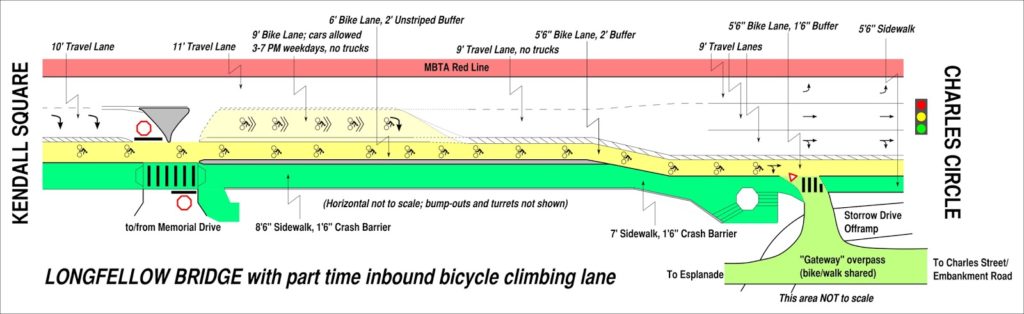

Here’s a graphic. I’ll make more sense of it below (Click to enlarge):

Here are the issues at hand:

- Peak bicycling occurs between 7:30 and 9:00 a.m., when bicyclists traveling from Cambridge, Somerville, Arlington and beyond converge on the Longfellow to commute to work in downtown Boston. For nearly any destination in Back Bay and Downtown, it is by far the easiest access.

- There is much less cycling outbound at rush hour because of mazes of one-way streets combined with heavy vehicular traffic on the other access roads (i.e. Cambridge Street).

- Thus, the highest bicycle use at any time on the bridge is during the morning rush hour inbound, but while plans indicate a wide, buffered bike lane going outbound, the inbound lane will barely be widened.

- Since the bridge has a noticeable incline from the Cambridge side, there is a wide spread of cyclist speeds, and it is reasonable to expect cyclists to want to overtake during heavier use times.

- With improvements to Beacon Street in Somerville as well as the access through Kendall Square, even more cyclists will crowd the bridge in the morning.

- With the expansion of Kendall Square and its reliance—to a degree—on bus shuttles, it can not be allowed to gridlock over the bridge during peak periods (generally evening rush hour).

Between Kendall Square and Memorial Drive, Main Street will merge from two lanes to one, to the left. The right lane will be for turns on to Memorial Drive only, and will be set off from straight-ahead traffic with bollards or a median.

Past the Memorial drive ramps:

The left inbound lane is kept at 11 feet and all non-Memorial traffic merges in to it before the bridge. The constriction for the Longfellow traffic is throughput at Charles Circle, so this shouldn’t dramatically affect traffic, especially since Memorial Drive traffic would exit in a dedicated lane. This will allow traffic to comfortably travel in it at all times. The lane would be signed as Vehicle Traffic, All Times. It would be separated from the right lane by an unusual marking such as a double broken white line.

The right inbound lane should be narrowed to 9 feet in width. Height restrictions (chains hanging from an overhead support) could be hung at intervals to discourage trucks and buses but signage would likely suffice. It would be signed as Bikes Only Except Weekdays 3 PM to 7 PM. No Trucks or Buses. It would be marked with diamonds or some other similar feature as well as “Sharrows” and separated from the bike lane by two solid white lines with no painted buffer in between, potentially with infrequent breaks.

The bike lane would be 6 feet wide and the two lines would serve as a 2 foot buffer at evening peak. It would be signed as a regular bike lane.

This will extend to the top of the bridge where the grade evens. Beyond that point, there is less need for a “climbing lane” for cyclists, and the bike lane will taper to one, buffered lane. The left lane stay 11 feet, and the right lane 9, but it will be open to cars at all times, with a continued buffered bike lane. Having the right lane closed to trucks and buses will dramatically increase the comfort level for bicyclists who are often squeezed by large vehicles, who will have no business in the right lane.

At the Cambridge End of the bridge, the merge to one lane before the Memorial Drive will funnel all Cambridge-origin traffic in to the left lane (this is the only origin for trucks and buses which can not fit under the Memorial Drive bridges). During non-peak afternoon hours, the Memorial Drive intersection would then join this traffic in a short merge lane after crossing the bicycle facility. At peak hours, it would continue in the right lane. This means that for a truck or bus to use the right lane, it would have to actively change lanes, meaning that even during rush hour, bicyclists would not be pinched by frequent tall tour buses and delivery vehicles. And at other times, most of the origin traffic from Cambridge would already be in the left lane, and only the Memorial Drive traffic—which already stops at a stop sign—would have to be signed in to the lane based on the time of day. The irregular lane markings will clue most drivers in to the fact that there is something different about the bridge, as will signage placed on the bridge approaches.

At the Boston end of the bridge, just before “salt/pepper shaker” the bridge could be widened (for instance, see this older image) to allow bicyclists to stay in a buffered bike lane and cars to sort in to three full (if narrow) lanes. However, two lanes might be preferable to allow trucks and buses to get from the left lane on to Charles Street (or such vehicles could be forbidden from this maneuver and forced straight on to Cambridge or left on to Embankment Road). In this case, enough room for side-by-side cycling in a bike lane—at least 7 or 8 feet—should be allowed (this is not showin the above schematic).

The potential for a flyover bike ramp to the unused portion of Embankment Road should not be discounted, either, as it would siphon much of the bicycle traffic away from the congested Charles Circle area. I called this the “Gateway Overpass” as a lower, gentler and wider bridge could span from the Embankment Road area across Storrow Drive to the Esplanade and allow easy egress to Charles Street across the Storrow offramp. The current bridge is narrow, steep and congested, and provides far more clearance over Storrow Drive than necessary. A new bridge is proposed (see page 10 of this PDF) but I think a level bicycle facility would be very helpful to help bikes avoid the congestion at Charles Circle.

If this project were found to be either dangerous for cyclists or a major impediment to traffic in Cambridge, it could be changed simply by restriping existing lanes, so there would be no major cost involved. If it constricted traffic enough, the lanes could be restriped with a buffer to allow a wider cycling facility inbound at all times.

I think it’s worth study, if not a try.

6000 Bikes Per Hour

A few weeks ago, a sea of cyclists pedaled (slowly) through Cambridge. The city has two annual recreational rides, complete with police escorts, where hundreds of bicyclists take to the streets. I took a video of the procession through Inman Square and it got lost in my phone for a while, but recently resurfaced and made it to Youtube.

It’s not that much to watch, unless you really like watching chatty cyclists at low speed, but it is illustrative how space-efficient cyclists are. The video lasts a bit shy of three minutes, and for about 2:30 of that (give or take) the swarm of cyclists passes by. I happen to know that there were about 250 (actually 258, according to the website). But let’s use round numbers—even at low speed there were 100 cyclists passing by per minute.

Which is extremely efficient.

On a freeway, a lane of traffic can only carry at most 2000 vehicles per hour—beyond that the roadway devolves quickly in to gridlock (and the number of vehicles drops). Yet one lane of bicyclists can accommodate three times as many people—you’d have to have three or four people in every car on a freeway to have the same level of service. Want to fill buses? Fine, but you better be able to get a full bus through every 30 seconds to match a lane of cyclists. Rail can surpass this capacity—at rush hour the Red Line in Cambridge peaks over 10,000 people per hour, and some lines in New York go past 20,000—but you need a bit more infrastructure to run such rail routes.

Since bicycles take up far less space than vehicles, they use road space much more efficiently than vehicles. Even if a rate of 6000 per hour necessitates a police escort, it’s still a testament to the efficiency of the bicycle.

Longfellow Bike Traffic update

I came in this morning across the Longfellow. As I jockeyed for position through Kendall, I knew it was going to be busy on the bridge. I’ve seen ten bicycles per light cycle on the bridge, but today the lane was chock-a-block with bikes all the way across the bridge. With minimal auto traffic, faster cyclists were swinging in to the right lane and passing slower cyclists. And when we got to the bottom, well, it was quite a sight.

I came in this morning across the Longfellow. As I jockeyed for position through Kendall, I knew it was going to be busy on the bridge. I’ve seen ten bicycles per light cycle on the bridge, but today the lane was chock-a-block with bikes all the way across the bridge. With minimal auto traffic, faster cyclists were swinging in to the right lane and passing slower cyclists. And when we got to the bottom, well, it was quite a sight.

I quickly hopped the sidewalk to take a picture. By my quick count, there were 18 cyclists in line waiting for the light to change at the bottom of the bridge. Last month, I’d assumed 10 bicyclists per light cycle, which would equate to 360 per hour. At 18 bicyclists, this is an astounding 648 bicycles per hour, or one every six seconds. That’s nearly as many vehicles as use the entire bridge in the AM peak (707). And this is despite the fact that the Longfellow is a narrow and bumpy bicycle facility.

So it is a shame that the current plan for the bridge allocates just as much space to vehicles, and does not appreciably expand the inbound bicycle facility. As we crossed today there were few vehicles, but bicycles could barely fit in the lane. Since the bridge hasn’t been rebuilt yet, there is still time to advocate for fewer vehicle lanes (one lane expanding to two would be mostly adequate) and a much wider bike lane allowing for passing and a buffer.

The current bicycle counts are only for the evening commute where, as I’ve pointed out before, it’s much harder to get to the Longfellow due to traffic, topography and one-way streets. I think it’s high time for a peak morning bike count on the Longfellow. And time to suggest to MassDOT they reexamine the user base for the roadway before it gets reconstructed and restriped.

Plus, if we have 650 bikes per hour using the current, subpar facility, imagine the bike traffic once the lane is wider and well-paved. To infinity and beyond! Or, at least, to 1000.

Moving Bicycles, part deux

Update: the train sold out in 12 hours.

A few weeks ago, I wrote about trainloads of bicycles. The Boston Globe has an article about the bike train, and it’s trending in their most viewed list. It should be exciting; I’m hoping the line for tickets isn’t too long over at South Station (I’m headed over there later to buy my ticket).

Now, it’s entirely possible that fewer than 700 bicyclists will buy tickets, and there will be no mad rush or secondary market. It’s also possible the train will sell out. (I’m only buying one ticket, buying extras to make a profit seems a bit uncouth.) In that case, here is Ari’s Unofficial Guide (I’ve written other unofficial guides in the past) To Getting To Southborough If You Can’t Get On The Train. In order of feasibility:

- Take the 8:30 and bike out to Hopkinton from Framingham. It’s 7 miles from Framingham to Hopkinton, which is only 4 miles further than the ride from Southborough. The train gets in at 9:20, which gives you a good hour and a half to bike up the hill to the start. If you were really keen, you could bike out to Southborough (6.5 miles) and join the ride there. One caveat is that they may be somewhat reticent to put a bunch of bikes on this train, but since Framingham is the final stop getting all the bikes off won’t delay any other passengers. Just make sure to leave room for the “normals” on the train. Need to kill an hour? There’s a bar in Ashland right on the course. Hopkinton isn’t dry, but there don’t seem to be many bars there. Update: The MBCR tweeted that it is a “regular train with room for only a few bikes.” So if you take it, arrive early, board early, and then get ready to get off quickly in Framingham. This train turns and is the 9:45 back to Boston, so it can’t stand to get delayed by an hour. Make sure to leave a couple of cars bike-free for non-cyclists. And consider buying a higher-zone pass to give the T some extra dollar bills.

- Take the 9:20 to Franklin. At 13.1 miles, this is a longer ride than the Framingham option, but it does leave a bit later. The train gets in to Franklin at 10:12, more than half an hour before the extra train gets to Southborough. From there it’s a ride mostly along back roads with one big hill at the end in to Hopkinton (the ride from Norfolk, the stop before Franklin, is not much longer, and you get an extra 7 minutes to ride). It’s probably a very nice ride, but you should be able to ride it in an hour to meet the rest of the gang from the Extra. Assuming a 45 minute run time, the Extra will arrive at 10:45 and should be done unloading by 11:15, and it’s a 15 minute-or-so ride to the start from there. If you can ride 12 m.p.h. you should be able to get to the start around the same time. (i.e. don’t try to do this on a Hubway, but if you’re a roadie, you should be fine.) See the suggestions above to keep the train, and yourself, on schedule.

- Just get on your bike and ride! Who’s not up for a metric century in the dark, anyway? You could trace Paul Revere’s footsteps (that’s what the holiday is all about—it’s not just a random day off for government workers) and ride up the Minuteman to Lexington and on to Concord. (This is more like 70 miles, and more if you follow Paul Revere’s route through Charlestown and Medford.) Then drop south to Cortaville/Southborough, meet the train, and ride on.

- Play coy, catch the 11:00 to Framingham and ride from there. For this option, get on the 11:00 train and buy a ticket to Framingham. Tell the conductor that you live there and are riding home, and that is within the bike regulations of the T. The train gets in to Framingham at 11:50, so you would have plenty of time to detrain and bike backwards on the course to go and meet the rest of the ride (or just hang out in Framingham; the first riders will shoot down the early hills in 15 minutes easily). You wouldn’t get the full experience, but it would work, in a pinch. Major caveat: even if you cite policy, they might not let you on this train.

- Play coy and try to catch the 11:00 to Southborough. (Not Suggested) Word on the street is that bikes won’t be allowed on the late train. There’s a canard that it will be full from Red Sox traffic from the game which starts at 1:00; I don’t believe this. But they don’t want a ton of bikes clogging the train and slowing it down; that’s why they’re running the extra. Still, it might work as an option, but I wouldn’t suggest it. If you were to take it, you’d arrive at midnight, and have a tough time getting to Hopkinton by the start, although you could probably catch some stragglers. If you are going to do this, I’d suggest buying a ticket to Worcester, claiming that’s your final destination, and getting off at Southborough. Unless there’s no one else getting off there. Have fun biking home from Worcester. (Actually, this train turns in Worcester and runs back to South Station, so you’d get a nice, dark train ride. Fun!) Anyway, don’t do this.

How do you move 1000 bicyclists by train?

This seems like it should be a rhetorical question. It’s not.

In 2010, about 70 bicyclists got onboard the late train to Worcester at 11:00, biked to the start of the Boston Marathon at midnight, and rode back in to the city. In 2011, 250 bikers showed up. Last year, by most estimations, 750 bicyclists made the trip, 150 on an early twilight ride and 600 on the traditional midnight ride.

If history is any guide—if the event triples again in size—2000 bicyclists will attempt to cram aboard the train and get 25 miles west to Hopkinton. Even if the growth of the event slows, a good 1000 bicyclists will likely show up to the event. (It is being advertised as “limited space” right now—we’ll see what happens.) The issue here is that with 600 bicyclists last year, the MBTA (well, really the MBCR, which operates commuter rail service) had to couple two trains together with 14 cars in order to accommodate these travelers. Any significant increase will have to have advanced planning, or some riders will get left behind.

While no one will lose their job if they can’t fit on the train (i.e. no one is missing work due to an overcrowded train), it would be lost revenue for the T, and bad publicity. The event garners some news coverage and probably will continue to do so, and if these cyclists are unable to cram aboard the Midnight Marathon train they’re less likely to take their bikes aboard trains the rest of the summer, and genrally at off-peak times. This is discretionary ridership which adds revenue without adding operating costs (or crowding rush hour trains). It’s in the T’s best interest to make sure everyone gets onboard and happy.

The problem is that unless changes are made, the train is nearly maxed out. So, there need to be some strategies to maximize the number of cyclists per train, streamline boarding and detraining, and have enough room to get everyone to Southborough, and staging them not in an intersection. Oh, and garner enough revenue for the MBTA that it is worthwhile to run extra trains to accommodate these passengers.

Maximizing cyclists on each train. Last year, when lines of cyclists snaked through South Station and on to the platforms, there were few guidelines to maximizing the number of bikes on board. The T ran single-level coaches (so cyclists didn’t have to haul bikes up and down stairs—this is probably for the best) with, for the most part 2-3 seating. For the most part, bikes were set in to the three-seat side of the car, and people sat in the couplets. This meant that, for all intents and purposes, 40% of the seats on the train were occupied.

This can be improved. With a minimal bit of cajoling, three bikes can be fit in each row. This means that every six rows of seats can see 15 bikes and 15 passengers. How? The first row has three bikes and two seats, so there’s a leftover passenger. The second row has three bikes and two seats, so there are now two leftover passengers. This goes on until you get to the sixth row which has five extra passengers and, very conveniently, five seats. Fill those up and start from scratch. You’ve raised capacity from 40% to 50%. With a seven car train and 120 seats per car, you can now accommodate 420 passengers.

How do you assure that there are three bikes per seat? Get volunteer riders-turned-ushers to enforce these rules. Have them walk down the cars from either end and assure there are three bikes to a seat and nothing goes empty. This doesn’t have to fall on T employees (who were mostly amazed at the turnout last year); I’m sure a couple dozen volunteers could be marshalled in to showing up at 8 to make sure everyone gets on the train. I’d probably be one.

Streamline boarding and detraining. Boarding is relatively simple at South Station. It’s time consuming, but with wide, level platforms it is relatively easy. The goal should be to get people on the train early, and board multiple cars at once. Last year people seemed to board one car until it was full and then move to the next. If we know how many bikes can fit in each car (and we should, see above) we can shepherd carloads of cyclists down the platform to the further-down cars and have everyone board at the same time.

Last year was that the extra train called in didn’t arrive until after 10, and people spent a while waiting (although the service did leave on time). If there are multiple trains, when a train is full, it should go. Last year the train had to be staged—detrained in sections—which more than doubled the time it sat at the station. In fact, here’s an idea. The 11:00 train makes all stops to Southborough. It should be boarded full except for one car, which can be reserved for “normal” passengers, and leave at 11:00 and make all stops. A second special train could begin boarding a bit later—say, at 11:00—and make an express run to Southborough (in about 35 minutes). It could cross over at some point and detrain on the inbound track (since it would then turn back to Boston) at the same time as the first train, doubling the speed people can get off. If there was a need for three trains, an early express could make a run out to Southborough and clear the tracks before the later trains arrived. It’s not like there is a lot of traffic on the line on Sunday evenings, so all of this would be possible.

In fact, there is a large parking lot on the inbound side, which would be a better place to assemble than last year when cyclists took over the streets (not that there was much traffic).

Sell and collect tickets. This worked well last year, for the most part. One change is that this year many participants may use smart phones to buy their tickets, and a question is whether there would be an issue with checking these tickets en masse. A certain suggestion would be to cordon off the platform at boarding time, and check tickets before boarding, so conductors wouldn’t have to ply the coaches en route.

Finally, it might be advisable to suggest that Midnight Marathoners buy a higher-zoned ticket to help the T cover the costs of this train. If the ride organizers told everyone to buy a Zone 8 one-way ticket, it would only be a dollar or two more for each rider, but it would be a few thousand extra for the cash-strapped T. Furthermore, requesting that riders buy a specific ticket ahead of time (Zone 9, for instance, which otherwise serves only the TF Green airport) could give a pretty good read on expected turnout. They are doing a tremendous service to the community by running extra-long trains, or extra sections, and putting a little extra money—which most anyone riding their bike at midnight on Marathon Monday can afford—in their coffers is good for all.