Everything is interconnected.

That should be the lesson of any transportation infrastructure project. Everything moves together. One part is always related to another. A change to one piece of infrastructure may have effects—positive or negative—across modes, across time, and across a region. In some cases, a project in one area can have a major impact on a seemingly disparate project somewhere else. We can’t think of transportation projects in a silo; instead, we must think of everything is interrelated.

South Station Expansion: Supply vs Demand

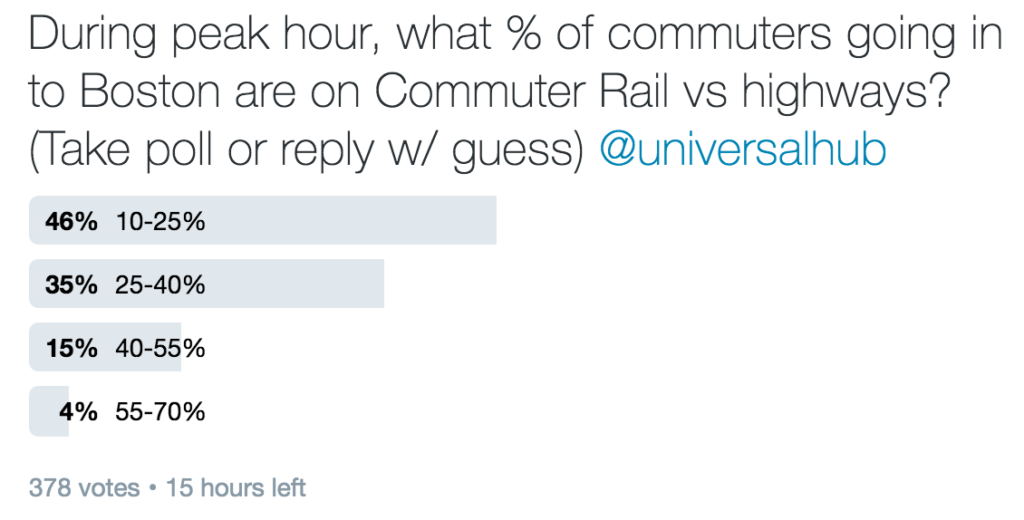

Which brings me to the South Station Expansion (SSX) project. This behemoth is a decade-long (or more) project of dubious value. Of most value is rebuilding the Tower 1 interlocking, which, when it fails, has huge service impacts for the entirety of the south side Commuter Rail network, impacting tens of thousands of commuters. Of more cost, and less apparent benefit, are plans to buy the post office building and build more tracks at South Station. SSX poses the current capacity issues at South Station as a supply problem, and therefore sees the solution to build more supply. But what if, instead, we addressed the demand?

There are two ways to think of the demand at South Station, and how to mitigate it. One is to look at the time which it takes each train to platform, let passengers off the train, have the crew change from one end of the train to another and perform a brake test, and board passengers for the destination (the passenger movements and crew end change can happen simultaneously). Right now, at rush hour, there is a maximum of 20 Commuter Rail trains per hour at South Station, spread across 11 tracks used for Commuter Rail (the other two are used for Amtrak). This means that the average occupancy time of a track at South Station is 33 minutes.

This is not exactly good. At outlying terminals, trains frequently turn in as little as fifteen minutes; most Worcester Line trains, for example, spend 20 minutes or less from the time they arrive at an outlying terminal to the time they leave. Even taking into account higher passenger loads at the terminal station and the need to empty the train before refilling it (given the width of the platforms), as well as extra time to traverse Tower 1, something less than 33 minutes should be possible. Let’s assume that an average turn time of 25 minutes were feasible at South Station. This would allow 26 trains per hour to use the terminal’s 11 Commuter Rail tracks, a 30% increase over the current “capacity” without building a single new track.

There’s another way to look at SSX as a demand issue rather than a supply one: run fewer trains into the station. In most cases, this is a non-starter: the trains which run into the station are near or at capacity, so running fewer would cause more crowding and provide less service; even if longer trains were run where possible, they would be even more infrequent than the service provided today. There is an exception: the Needham Line could be replaced with rapid transit service and removed from South Station entirely, freeing up 10% of the capacity there without lifting a finger, at least on the Commuter Rail side. Reducing demand to preclude building more supply could save billions of dollars, and while converting the Needham Line to rapid transit wouldn’t be cheap, it might be significantly less expensive than South Station Expansion.

Needham Line Replacement

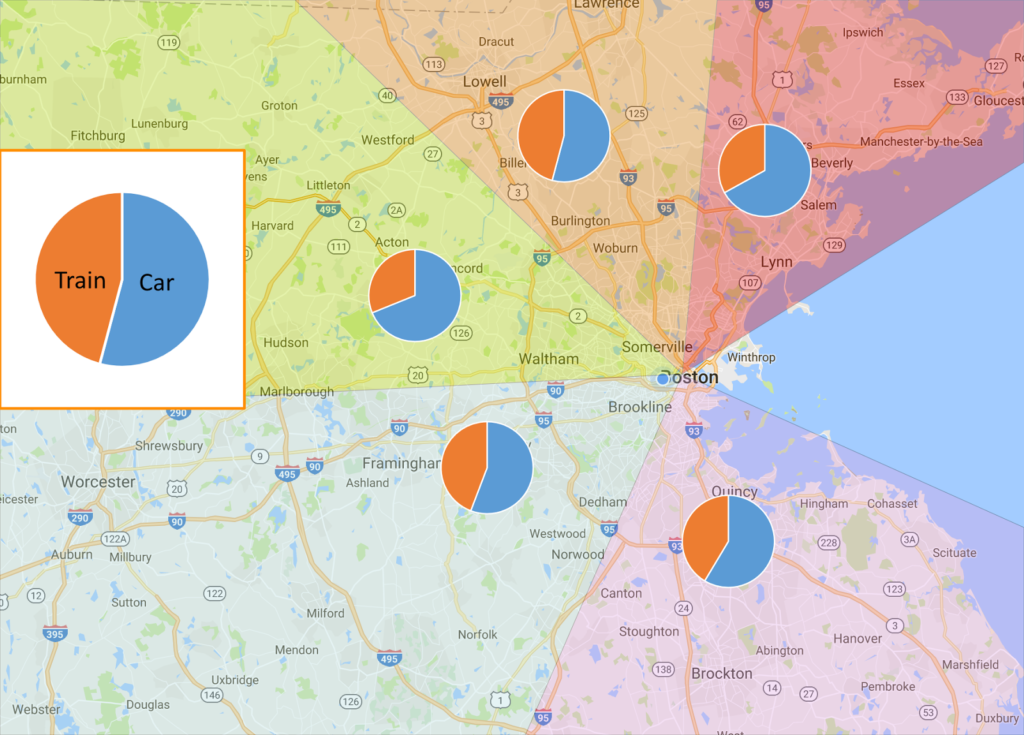

Other than the Fairmount Line, the Needham Line is Commuter Rail’s shortest. It runs less than 14 miles, splitting off of the Northeast Corridor at Forest Hills, running through Roslindale and West Roxbury to Needham Junction, and then curving back northeast to Needham Heights. (The track beyond there originally connected to what is now the Riverside Line.) The end of the line at Needham Heights is less than 10 miles, as the crow flies, from Downtown, closer, in fact, than the Green Line terminus at Riverside. Yet a train to South Station takes 46 minutes to complete the journey, making frequent stops between Needham and Forest Hills. Service is infrequent—about every 40 minutes—yet the line is still so crowded that it sometimes leaves passengers behind. This is probably because a typical rush hour commute time is even longer: the trip from Needham to Boston by car can take well over an hour.

This page recently detailed how a mile-long extension of the Orange Line to Melrose could, for a small investment, dramatically improve the service. Replacing the Needham Line would be a similar endeavor, albeit one at a larger scale. It would involve two line extensions, extending the Green Line south from Newton Highlands to Needham, and the Orange Line west from Forest Hills to West Roxbury. Most Needham Line riders would see slightly longer trip times to downtown Boston, but this would be made up for by dramatically-increase capacity, significantly shorter waiting times and much more frequent off-peak and weekend service (the Needham Line doesn’t operate on Sundays). It would also have cascading benefits throughout the regional transportation network.

Orange Line Extension to West Roxbury

Extending the Orange Line to West Roxbury would be a relatively simple project, as far as rail extensions go. Southwest of Forest Hills, the Orange Line terminates in a small, four-track yard, where trains can be stored temporarily at the end of the line. This yard happens to be adjacent to the Needham Line tracks, which extend to Roslindale and beyond. While it was originally a two-track right-of-way, the current Needham Line operates with a combination of single track and dual track, with most stations on the single track portion. Any conversion to rapid transit would require double-tracking of the line, which is generally easy in the existing right-of-way, except for two bridges in Robert and LaGrange streets, which have wide bridge abutments, but only a single trackway.

A trip to Back Bay station would take two or three minutes longer on the Orange Line than it does today on Commuter Rail, but rather than a train once every 40 minutes at rush hour and every two hours midday and Saturdays (and no service on Sundays), trains would come every few minutes, all day long. Given the current fare structure and the infrequency of service, many passengers would shift from taking a bus to Forest Hills and changing to the train there to a direct train trip, freeing up buses to be used on other routes in the region.

The largest cost in converting the line to rapid transit would be from the development of stations, which would generally have to be rebuilt with new platforms and vertical circulation, as few are ADA-compliant and some rely on pedestrian grade crossings, which are not feasible with third-rail power systems. The four new stations would replace the existing Commuter Rail stations, although it may be possible to consolidate the West Roxbury, Highland and Bellevue stations, which are less than half a mile from each other. The line may benefit from having a new station to the west near the VFW parkway. This would provide access to new housing developments there, the potential for a park-and-ride facility, and a station within walking distance of the VA medical center there, which is currently difficult to reach by transit and surrounded by a sea of parking. There are also several parcels of low-density strip malls which could be redeveloped as transit-oriented development (like this one), increasing ridership at the station as well as providing much-needed housing for the region. (There’s also a major electrical substation there, which would provide power to the line.)

West of there, there may be need for a small storage yard along the current right-of-way, especially if additional vehicles were needed to provide service (the Orange Line fleet as constructed today can barely keep up with current demand, but the new expanded fleet will allow more frequent service). The right-of-way across the river could be converted into a multi-use path, extending west across the Charles, through Cutler Park to Needham Junction, the Green Line extension, and the path southwest to Dover and beyond.

Why not extend the Orange Line further west? One is technology and the line’s profile: it would only be able to run as far as Needham Junction, north of which there are grade crossings incompatible with third rail electrification. It would require rebuilding three long bridges across the Charles, a drainage in Cutler Park and 128, which are currently single-tracked, and dealing with the current grade crossing in the golf course west of Hersey. But mostly, it’s because the population profile. The stations in Needham serve a much less dense population than those in Boston, and extending the Orange Line two miles across a park to serve Hersey and Needham Junction would be far more expensive than using the Green Line, which is needed in Needham because of the grade crossings there.

Green Line Extension to Needham

The outer portion of the Needham Line, from Needham Junction to Newton, looks very little like the line in West Roxbury. Today’s Needham Line is made up of three different railroads, a branch of the Boston and Providence to Dedham built in the 1840s, the Charles River Railroad built in the 1850s, and the portion between West Roxbury and Needham Junction, built in the early 1900s. While the B&P was grade-separated, the Charles River Railroad was not, and there are eight grade crossings between Needham Junction and Newton Highlands. This lends itself far more to a light-rail operation, with overhead power and smaller stations. Luckily, the Charles River Railroad split off the Boston and Albany’s Highland Branch at Newton Highlands, and the Highland Branch is today’s D Line.

Extending the D Line the first mile to Oak Street would be simple. The right-of-way is 85 feet wide, plenty wide enough for two Green Line tracks and the parallel Upper Falls Greenway (a 2017 document suggests there might be some areas which would require additional retaining walls, although the width of the corridor can easily accommodate two tracks). There are no grade crossings, existing mixed-use areas, and significant opportunities for further development in the corridor. The costliest item may be building a junction between the lines past Newton Highlands.

West of Oak Street is trickier, as bridges over both the Charles River and Route 128 would have to be widened and replaced. The bridge over the Charles is a single track, while the bridge over 128 was removed during the wildly expensive “add-a-lane” project (originally, the scope included rebuilding the bridge, but it was deleted out as a cost-saving move; although MassDOT would be responsible for restoring the bridge if the MBTA requested it, theoretically using highway funding; abutments are built to accommodate two tracks). From there, the right-of-way extends in to Needham, where it eventually joins up with the existing Commuter Rail line. Grade crossings would have to be added and power run (there is an existing substation adjacent to the line at the junction with the current D Line, as well as high voltage power at Needham Junction) and stations built, although grade-level, Green Line stations would be far less costly than those on the Orange Line, since they would consist of little more than concrete platforms and shelters. If retaining service to Hersey was desired, it could be served by a single-track extension from a terminal at Needham Junction (and theoretically, a single track Green Line would make more sense for a line from Needham to West Roxbury than Orange Line service, if service were desired along this leg).

The trip from Needham to Downtown Boston would be five to ten minutes longer than the Commuter Rail trip (more of an impact from Needham Junction and a minimal change from Needham Highlands), although improved Green Line fare payment and boarding may help speed trips on the line. There would be a major advantage for trips to the Longwood Medical Area, however, since the Longwood Green Line station would be just 25 to 30 minutes from Needham, and it is located significantly closer to the major employment center there than the Ruggles stop on the Commuter Rail is today. And, of course, trains would run every eight or ten minutes, as compared to the less-frequent Commuter Rail service today.

Since everything is interrelated, the biggest obstacle to this project may actually be the core capacity of the Green Line subway in Back Bay. From Copley to Park, there is a train every 90 seconds, which is close to the capacity of the line. While the MBTA has proposed adding longer vehicles to the line to increase capacity, adding a branch to Needham might overload the central subway system, even if service to each of the sub-branches (Needham and Riverside) were cut to every 8 to 10 minutes at rush hour, it would put more pressure on the line. There is, however, an escape valve. The design of the Kenmore station would allow some trains to terminate there, loop over the main trunk of the subway, and turn back outbound, without impact the Copley-Park segment. While this would incur a transfer for some passengers, they could board any other train in the station and continue their trip (and any passenger going to a destination west of Kenmore, like the LMA, would have no impact). This would allow service on the Riverside and Needham branches to maintain high frequencies without adding congestion downtown. (There are other solutions as well, but may be significantly more capital intensive than this, which would be free.)

Green Line Storage Capacity

A major benefit, however, would be the ability of the Needham extension to provide additional rail car storage for the Green Line. Once the Somverille Green Line extension opens, the line will need additional cars, and if the fleet is upgraded from 75-foot cars to 100-foot cars, as is proposed, the current storage facilities will be unable to cope with the number of cars on the line. (Of course, if service were run 24 hours each day, enough cars would be operating on the line as to reduce the need for more storage.) Cars are currently stored at Riverside, Reservoir, Lake Street (at the end of the B Line) and at Lechmere. The Lechmere yard will be replaced with a new facility as part of the Green Line extension project, but there are otherwise few areas to expand train storage, and the Needham Branch would require more cars, and more storage.

Needham Junction, however, provides that room. The current Riverside yard provides storage for 6000 linear feet of railcars, which accounts for about half of the space in the yard (the rest is the T’s heavy maintenance facility for the Green Line). Needham Junction could easily accommodate that size of facility (see a comparison here) and, if expanded to fill out the wye there and the adjacent power line right of way could store triple the amount, enough to store the entire current fleet (including the forthcoming Type 9s), so certainly enough to provide additional capacity for future fleet needs. Part of the site could also be used as a park-and-ride lot or for transit-oriented development (the portion not already owned by the T is owned by a landscaping company).

Overall Benefits

Extending the Green and Orange lines to Needham and West Roxbury would be a major undertaking: a multi-year project which would cost hundreds of millions of dollars. And yet, its effects would be felt far outside of Needham and West Roxbury. It would provide:

- Much more frequent service for Needham, West Roxbury and Roslindale commuters

- More capacity at an unexpanded South Station, to add service to other Commuter Rail lines, and the ability to push back the huge expenditure required to add capacity to South Station

- Additional “slots” on the Northeast Corridor, to allow more service on this particularly-constrained portion of the Commuter Rail.

- Additional storage for Green Line trains

- More bus service in the entire region, since many of the bus routes currently serving Forest Hills could be reduced in frequency (given the Orange Line in West Roxbury) and cut back from Forest Hills to Roslindale or other Orange Line stations. The buses saved could be reallocated to other parts of the system. In addition, the 59 bus in Newton and Needham could be truncated and replaced with the Green Line.

- The reallocation of the three Needham Line Commuter Rail train sets, which would add capacity to the rest of the system and/or allow some of the most antiquated trains to be retired.

- A new greenway path connecting the ends of the Orange and Green line extensions to Cutler and Millennium Parks, across the Charles River, and south and west to Needham Town Forest and parks and conservation areas beyond.

Thus, extending the Green and Orange lines will not just benefit those along the Green and Orange extension routes, but also people riding buses, people riding the rest of the Green Line, and people riding Commuter Rail, as well as allowing the state to push back the need to build out the South Station expansion, and potentially explore opportunities to further address the demand side (by reducing turn times further or building a North South Rail Link) instead.