Sometimes I take some issue with CW’s headlines, but I like this piece overall. (I wrote it. Suggested headline was “to build SCR, look to the roads.”)

A few in-the-weeds notes:

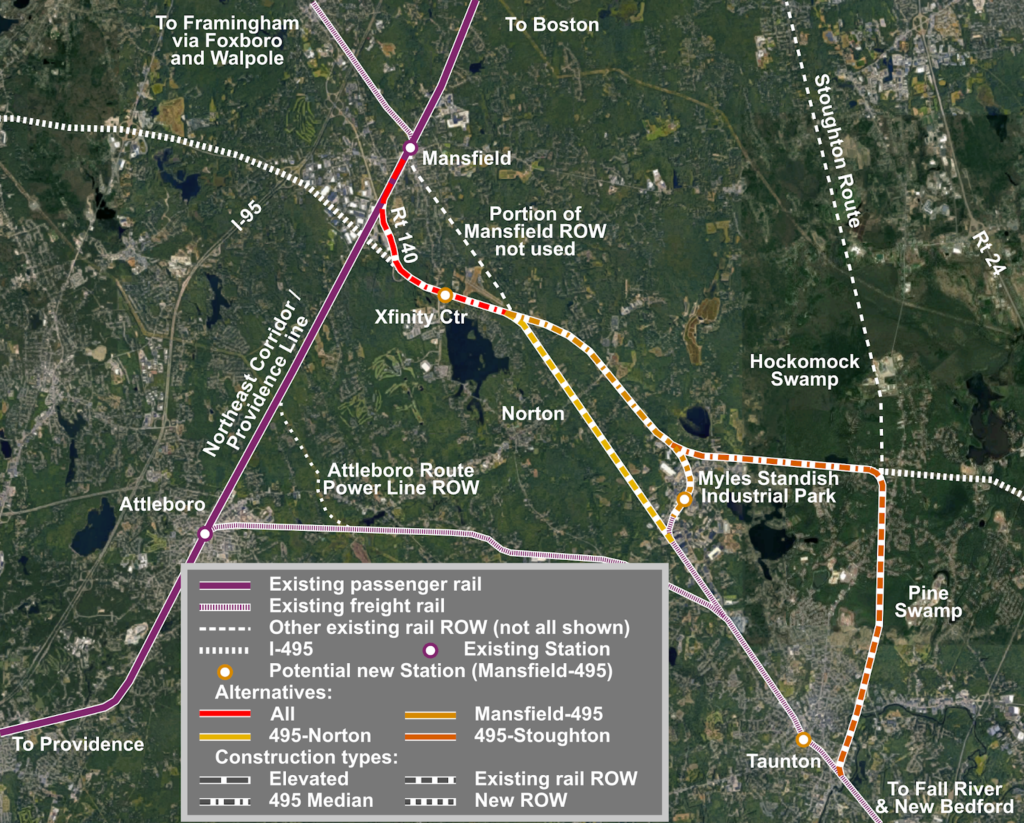

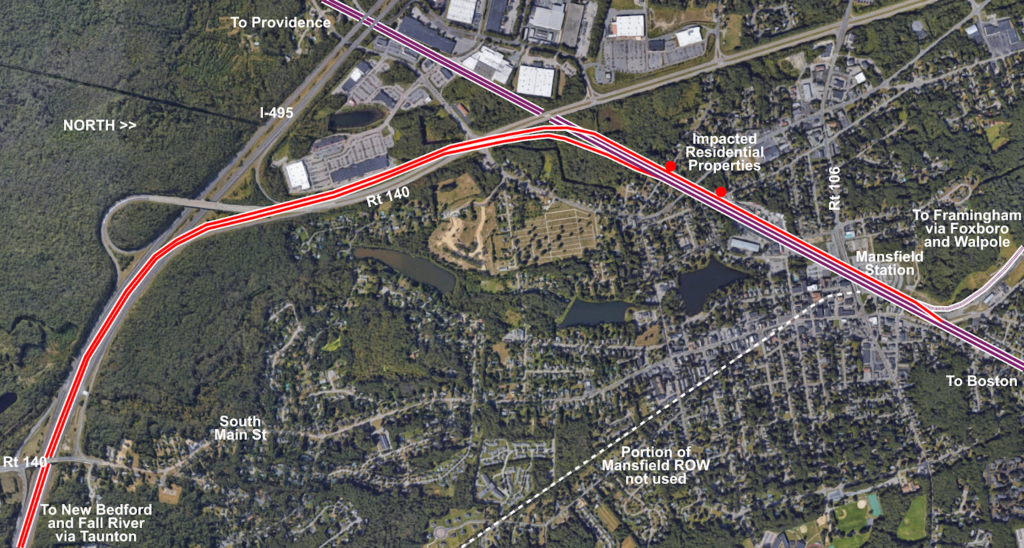

The route straight along the right-of way in Norton looks nice, but it has a few issues. It passes quite near to several homes, and would probably raise NIMBY issues. It is mostly owned by the town of Mansfield, which has a sewage treatment facility in Norton near the Taunton Line, and uses the ROW for a sewer pipe, which might have to be relocated within the right-of-way. There are some very low-angle grade crossings which would require extensive roadwork to make safe (or require grade separation). Extending down the 495 median to bypass this makes a lot of sense.

This post assumes electrification, although the original reason for the army corps to demand electrification was something about crossing the Hockomock Swamp. Still, electrification is the only way to allow high speed operations from Boston to Taunton, and between Taunton and Fall River and New Bedford. The maximum curvature on this portion of 495 is less than 1˚, which would allow 110 mph operation. Amtrak Regional trains reach Mansfield in 25 minutes from South Station, so even making stops at Mansfield and Myles Standish, an electrified Commuter Rail train could make Taunton in under 40 minutes.

Not only is the Taunton Station located closer to downtown using this route, it is also located adjacent to the main GATRA transfer point. Of course, fixing GATRA would help; Miles is not particularly enamored with their service. It would also be adjacent to some land which would be primed for TOD, and would likely increase in value if it were 40 minutes from Downtown Boston.

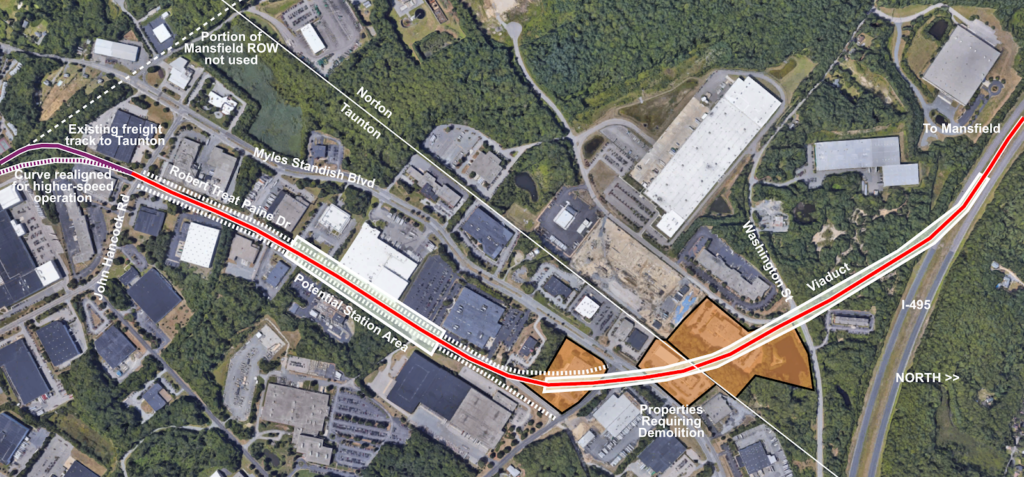

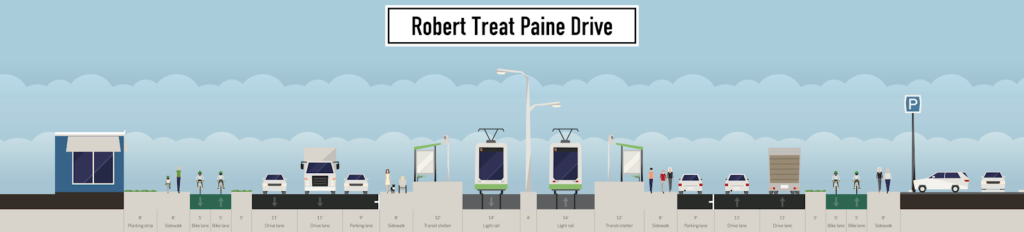

Myles Standish Industrial Park is sort of the wild card here. I am considering that having passenger rail access would be a net benefit, and that providing a right-of-way would not be particularly costly. The three buildings which would require takings would cost about $10 million; the additional land taking would add a bit more. I’d propose a viaduct to access the industrial park and cross the main roadway (Myles Standish Blvd)—which the current ground profile makes relatively easy—before running in the middle of Robert Treat Paine Drive, which could be relocated on to either side of the new rail right-of-way. It is at least 240 feet between any buildings in this corridor, the western portion of which has an overgrown and disused freight spur. A two-lane roadway could be built on either side with room to spare. The crossing of John Hancock would require an engineering decision of whether to build it at-grade or on a short overpass.

The “station area” would allow access to most of the industrial park (although better bicycle/pedestrian access would help) and may allow zoning changes and higher density. There is no housing in the park itself, but some nearby. Here’s what a profile of the roadway might look like, and there is plenty of room for all of this. (And, no, I’m not sure you need an eight-foot-sidewalk plus a two-way cycletrack on each side of the roadway, nor two lanes of traffic and parking for a road which currently carries 1500 vehicles per day, but the room is there. Also, imagine the streetlights in the middle are catenary poles and wire.)

There are two potential issues building in the 495 corridor. The first is environmental. 495 crosses through the Canoe River Area of Critical Environmental Concern (ACEC), a good map of which can be found here. This would raise some permitting issues, particularly since 495 crosses the Canoe River twice, to assure that steps were taken to mitigate any impact to the surrounding environment. The ACEC was designated in 1991, long after 495 had been laid out and built; it’s safe to say that if the highway were built today, it would be built with a smaller footprint which would preclude its easy use as a railroad right-of-way.

The second issue is that 495 has sloping concrete bridge abutments. This would require some construction to demolish portions of the concrete, shore up the remaining concrete, and provide a trackway for rail service. An example is here on the corridor, here is a situation in Maine where a slope was changed to a retaining wall to allow a highway widening. This would be a minor issue, although the rail bed might have to be undercut slightly lower than the highway to provide clearance for any freight and electrification. There are a total of five over grade bridges along the highway; the only new rail bridges required would be the two aforementioned crossings of the Canoe River.

Next, a proposal for the Mansfield Station. Mansfield is one of the busiest Commuter Rail stations, with more than 2000 daily passengers and some trains picking up or dropping off as many as 400 passengers. By boarding at fewer doors and forcing passengers to climb stairs, this adds several minutes to each train passing Mansfield Station, potentially adding 10 minutes to the run time from Providence to Boston for busy trains. The station is on the STRACNET—the military rail network—route to Otis AFB (or whatever it’s called now) and requires wider freight clearances at stations (you can find a map of STRACNET toggling around here) and that is cited as a reason high-level platforms can’t be provided.

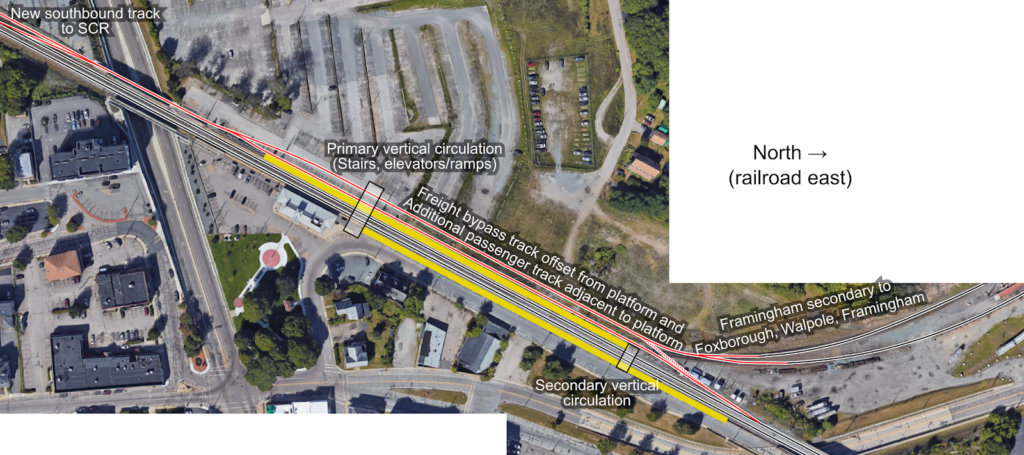

The idea would be to rebuild Mansfield Station as a three-track, two-platform station. The existing eastbound track (the number 2 track, “inbound” towards Boston) would remain in place, and a high-level platform would be built just east of the station house. The existing westbound track (the number 1 track, “outbound” towards Providence) would also remain in place, with a high-level platform built where the platform exits today. Two additional tracks would be added. The first would be a passenger track adjacent to the platform, branching off of the NEC east of the station. This would continue on as the southbound SCR track, eventually rising up and over the NEC to access 140 and then 495. (The northbound track would not have to cross the NEC and would merge in to the existing eastbound NEC track near West Street.) The second track would be a realignment of the Framingham Secondary, which would parallel the platform before merging in to the SCR and NEC west of the station, providing a wide freight route. An additional connection could be built between the NEC and the Framingham Secondary east of Mansfield if a wide route was needed there.

The original map (see the top of the page) proposes a station near the Xfinity Center. The concert venue is less-used than it once was (apparently at its peak, it hosted 80 shows annually, today it is more like 36) but it still causes traffic and today can only be reached by car (or, I guess, a cab or TNC from Mansfield). A park-and-ride station at Route 140 in Norton would provide a good park-and-ride location for people on 495 or who live in Norton and currently use the Mansfield P&R (with the additional benefit of reducing the number of people driving to downtown Mansfield just to park). The site there formerly contained an indoor soccer facility and has been vacant for years; there’s a plan to build a hotel there. MassDOT owns the three acres closest to the highway which could be used as a park-and-ride. As for the Xfinity Center, a train station would be about a 15 minute walk from the venue, mostly through the existing parking lots. Given the time to walk to a far-away car and get out is often longer than that, taking the train might be a good option for concert-goers.

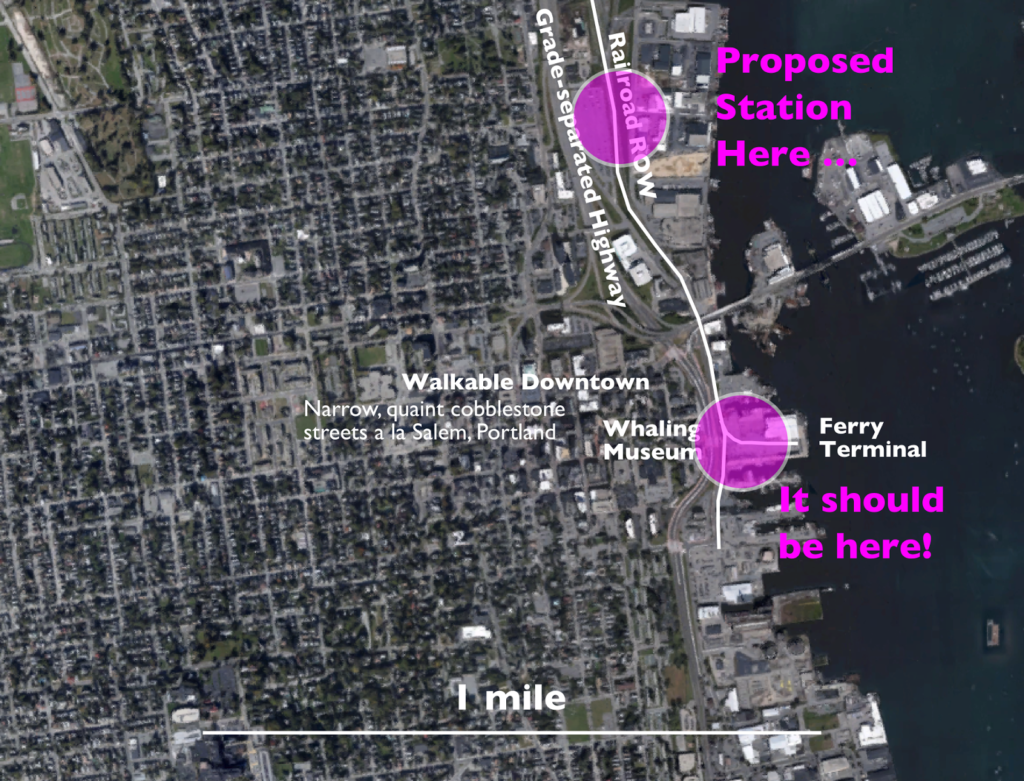

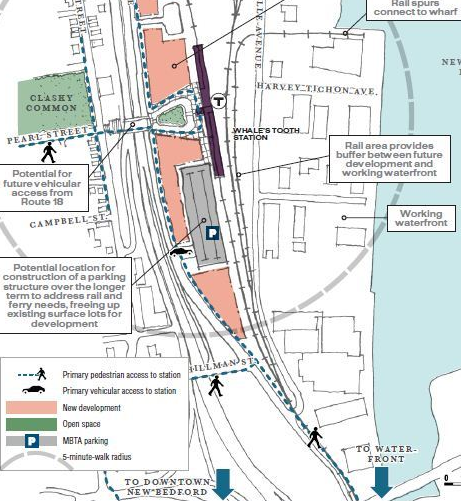

Finally, another plug for a direct ferry connection in New Bedford with a station adjacent to downtown. Getting to the Vineyard today requires a drive to Woods Hole (or in some cases, New Bedford, Providence or elsewhere) but since the majority of travel is via Woods Hole, it requires crossing the Cape Cod Canal, in traffic, a two-hour drive from Boston or more at peak times. With parking, taking a shuttle to the ferry terminal and the ferry itself, travelers need to budget four hours to get to the Vineyard. With a 51 minute travel time to New Bedford from Boston and an hour-long ferry ride this trip could be turned on its head, with two-hour travel times from Downtown Boston. Considering that there are millions of ferry trips made each year, and that the majority of visitors to the islands don’t bring a car, this would provide a much more convenient trip to the island and would probably garner high ridership, while removing vehicles from the Cape Cod bridges at peak times.