If you start walking or bicycling east in Cambridge from Mass Ave in Cambridge, you can go for six miles clockwise around the Charles River basin before you have to stop for traffic at the BU Bridge. Then the final mile back to where you started at Mass Ave requires crossing both the BU Bridge adjacent to the rotary and then Mass Ave at the foot of the Harvard Bridge. Yet if you were driving along Memorial Drive, you’d be able to proceed barrier-free: there’s grade-separation for cars, but not for people.

I’ve written before about how Memorial Drive can and should be reduced to two lanes, which would allow the parkland along the river to be widened significantly and given the traffic volumes—which match Nonantum Road in Newton, which was narrowed from four lanes to two—would not have a significant detrimental effect on traffic capacity. In fact, Memorial Drive has less than half the volume of Storrow Drive, across the river. So why shouldn’t it have half as many lanes? Indeed, the roadway was narrowed to a single lane during a sewer outfall project with no perceivable loss to traffic capacity.

The question then becomes how to handle intersections, where the current roadway crosses over or ducks under the main crossroads, with turning traffic crossing the bikeways and pedways, poorly-timed light cycles, and a number of dangerous facilities for people not driving cars. These roadways are optimized for the movement of cars, not for the safe and efficient passage of people using more space-efficient modes. However, it would be possible to move vehicles to the existing eastbound lanes and, with a few new signals to allow necessary traffic movement on and off of Memorial Drive, create a corridor which would allow the uninterrupted flow of people walking and biking from Western Ave to the Museum of Science, and allow people to make a 7-mile loop around the Charles River Basin without a single traffic light in their way.

The new signals would operate much like the signal at Charlesbank Road and Nonantum Road in Newton. They would only have a single turning movement, and would generally allow traffic movement in the through direction. Ample storage would be allowed for turning movements as required. And much of the existing ramp space would be changed from impervious land to parkland, for the use of people passing through or, given the larger parkland dimensions, spending time near the river.

Here are some detailed sketches of how each intersection could be rebuilt.

The BU Bridge

The BU Bridge rotary is crossed by the Reid Overpass, a 1930s structure which carries four lanes across the rotary. The rotary itself is poorly-designed for pedestrians and people riding bikes. The pathway is narrow, and requires crossing two separate portions of the BU Bridge roadway on walk signals, which sometimes requires a two-stage crossing. East of the rotary, the pathway is squeezed onto a narrow sidewalk along the roadway, and while a buffered bikeway has been painted to allow bicycles to more easily use the roadway, the facility is unfriendly for people. Meanwhile, through cars have a traffic-free trip across the overpass.

This plan proposes converting the Reid Overpass to a two-lane roadway and a bike path on the southern side. The existing ramps between the BU Bridge Rotary and Memorial Drive would be closed, with the northern ramps converted to two-way traffic. At the ends of each of these ramps, signals would allow traffic to move safely cross where necessary, with turning lanes provided to minimize any delays four through traffic. Westbound through traffic would encounter a single signal at the east end of the bridge, where there is not room for a merge. Eastbound traffic would encounter two signals, one at each end of the overpass. Given relatively low west-to-south and south-to-east movements, these lights would primarily allow through traffic.

This would dramatically simplify the bridge rotary, which could eliminate the traffic light allowing traffic from the rotary to enter Memorial Drive east. A traffic light may be retained for bicycles and pedestrians crossing the southern end of the rotary, but the overpass would significantly reduce this volume and it’s possible that, if it were safely redesigned, this signal could be eliminated as well. This would result in some tighter turn radii on and off of the BU Bridge rotary, but only for traffic going to and from Memorial Drive, which is a route which does not allow truck traffic outside of specific cases. Buses using the roadway (the CT2) would likely continue to be able to use the new alignment, or could be rerouted to use Waverly and Albany streets to get to Kendall Square, moving a stop a few hundred feet across the Grand Junction to do so. It’s also possible that the rotary could be reimagined as a single crossing, although the position of the bridge may make this difficult.

This plan would eliminate the right-on-red movement from the BU Bridge to Memorial Drive eastbound, which often crosses conflicting pedestrian movements (but is still better than the pre-2009 slip lane). The tighter turn radii would require slower traffic for cars entering and exiting the rotary. It would also allow a redesign of the rotary to provide safer bicycle movement and a bus priority lane, as well as significant new green space.

The Harvard Bridge

A mile to the east, Memorial Drive was routed under Mass Ave, also in the 1930s, with two lanes in each direction. Traffic from Mass Ave can turn in three of four movements; there is no provision for south-to-east turns other than a downstream U-turn, which would be eliminated if the roadway were narrowed (there are other routes to reach Memorial Drive on nearby streets). This intersection has a complex series of traffic lights and phases, and busy pedestrian movements in all directions, especially parallel to the river on the busy side path system.

This intersection would behave similarly to the BU Bridge. The riverside roadway and ramp system would be closed, with two new signals to allow traffic to move between Memorial Drive and Mass Ave as necessary. The signal at Mass Ave would be relocated to a single signal closer to MIT with, perhaps, a pedestrian phase for users who do not wish to use the underpass. Since the bridge over Memorial Drive is significantly wider than the Harvard Bridge, this would allow safe bicycle movement as well as turning lanes and queue jumps for transit vehicles in an area where these facilities are lacking today. With more room east and west of the underpass, there would be ample room for turning and merging lanes, so that while westbound traffic would have to pass through two traffic lights, eastbound traffic would be able to proceed unimpeded.

Bicycles and pedestrians would utilize a new facility on the existing eastbound lanes, which would provide a safe crossing of Mass Ave. Additional pathways could be incorporated to allow bicycle and pedestrian traffic to easily move between Mass Ave and the Memorial Drive underpass. By removing the onramps, there would be significant new green space added to the area, which would result in a 120-foot-wide Esplanade along the river by freeing up the green “island” in the middle which, today, is barely accessible because of the roadway. Some parking would be lost along Memorial Drive, but this could be compensated by adding parking spaces in the existing green space south of the two-lane roadway, and by widening the roadway slightly to allow vehicles to be parked more safely. Of course, parking should be a decision made after other users, especially bicycles and pedestrians, have been accommodated.

The Longfellow Bridge

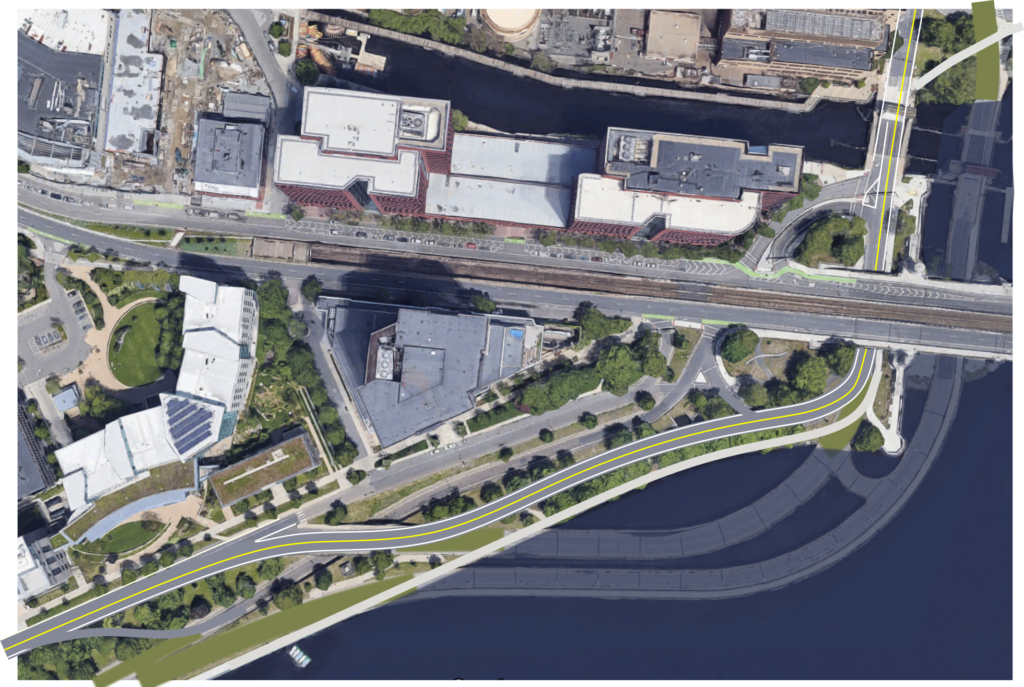

The Longfellow Bridge does not today require pedestrians to cross a roadway (or the Red Line) at grade, but there are two major issues with the roadway and parkland at this cross-section. The path along the river is very narrow on the draw span east of the bridge, and the “HAWK” signal west of there is poorly sited (also, HAWK signals are uniformly awful). The path itself lies alongside a four-lane highway which was built on stilts in the Charles River water sheet itself, so that a high-speed roadway could funnel traffic over the river and under the Longfellow Bridge, which benefits the driver at the expense of people walking, biking, and the health of the river itself.

Unlike at the BU Bridge and Mass Ave, this design would simply narrow the existing roadway to two lanes without adding any additional traffic lights (there is an existing pedestrian crossing which might be appropriate to retain along this portion of roadway, although pedestrian crossings could be handled at the existing crosswalks at either end). The existing underpass for traffic going from Memorial Drive to the Longfellow eastbound would be retained to allow traffic to pass there without requiring the use of a signal, although this could alternatively be used for bicycle and pedestrian traffic if a signal were added in front of Sloan. The roadway would be realigned on the original riverbank with a new pathway alongside, and the existing, highway-style bridges over the river would be removed, with the river restored, and potentially with a more active riverbank installed. The image above shows the extent of the existing bridges which would be restored to open river with this plan. This would allow the pre-1950s roadway plan to be restored, albeit with a wider green space along the river itself for people walking, biking, and utilizing the park as a park, not a highway.

Some Precedent

The DCR has begun a planning process for the western portion of Memorial Drive, from the BU Bridge past Harvard Square, but it has been widely panned as car-centric as it does not reduce the lane width or dramatically improve the pathway system, and does nothing about the BU Bridge intersection. However, there is some precedent for realigning roadways along the Charles River to benefit users, particularly those not using cars. In addition to the aforementioned Nonantum Road redesign from four lanes to two, Memorial Drive itself was relocated away from the river.

Well, not Memorial Drive exactly, but the eastern extension along Cambridge Parkway. The initial roadway followed Commercial Street, now Land Boulevard, inland from the river, with the area between the river wall and Commercial called “The Front.” In 1930, one of the earlier roadways was built on The Front and was labeled as the Northern Artery on some maps, which carried two lanes in each direction (albeit with bottlenecks at both ends). This was renamed Cambridge Parkway and became the main artery, with local traffic on Commercial Street. With the opening of the new roadways under the Longfellow in the late 1950s, the configuration was changed once again: Cambridge Parkway became the route for eastbound traffic, with westbound traffic moved back to Commercial Street. This configuration lasted until the late 1980s, when the industrial buildings were removed, the Cambridgeside Galleria built, and all traffic relocated onto a widened Commercial Street (which became Land Boulevard), with Cambridge Parkway reduced to a single lane westbound with a lane of parking. Thus, over the course of half a century, Cambridge Parkway changed its configuration nearly half a dozen times.

The rest of Memorial Drive has also been reconfigured. Until the late 1990s, the roadway was three lanes wide in each direction (imagine that!) and parking was allowed on both the inbound and outbound sides. The ramp from Mass Ave was two lanes, which merged with two other lanes, to create three lanes, plus a parking lane, which didn’t make sense except that DCR (well, at the time, MDC) seems to think that more lanes are always better. Parking was restricted and the park slightly widened at some point on the inbound side, but two lanes were retained, because gosh there have always been lots of cars here, right?

There’s no law that says that roadways must remain the same forever. In the case of Memorial Drive, what was intended to be a “pleasure drive” has become a riverside highway, with dangerous pedestrian crossings and high-speed traffic even if it doesn’t serve that many people in cars. With some common-sense, low-cost changes (except for some new roadway near the Longfellow, few of these changes would require more significant changes to roadways) could be made in a matter of months on a trial basis. Finally, with lower traffic and greater need for people to be outside, right now is the best time in the past 90 years to reclaim some of this road space for people.