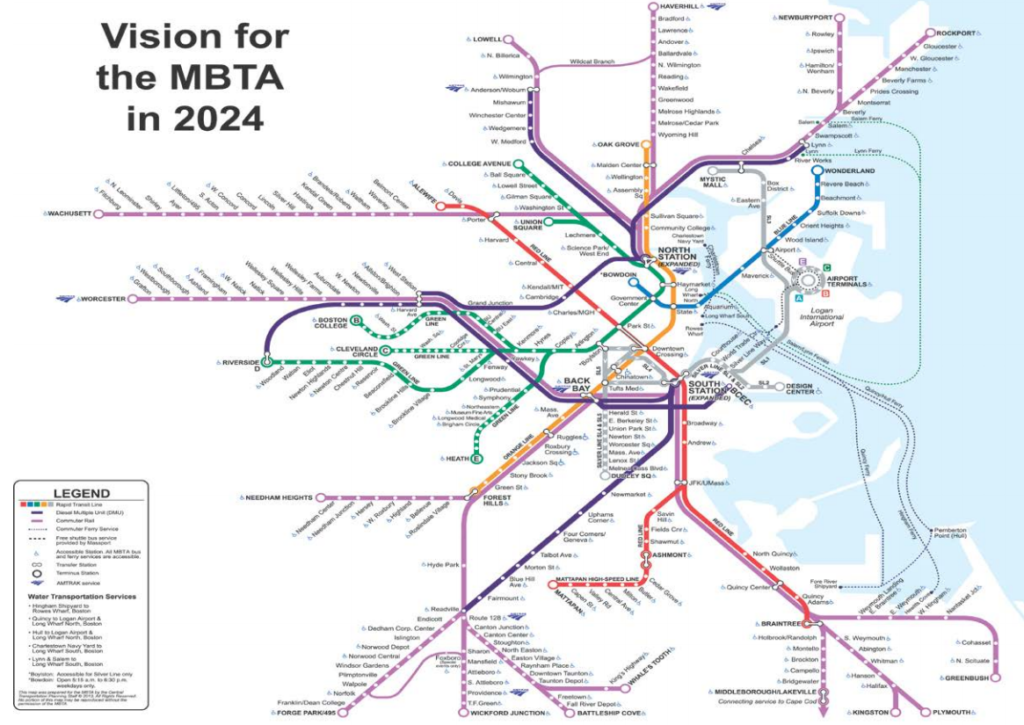

One of the many issues with the Allston project that I have been way too involved with is that the State maintains that they need a midday layover yard for Commuter Rail equipment. Why? Because they plan to add capacity to South Station and, since they can’t stack out-of-service trains in the terminal, need somewhere to store them when they’re not in use in the middle of the day. (Off-topic but relevant: the need for and cost of which could be obviated completely simply by building the North-South Rail Link; thru-running is so much more efficient that in Philadelphia SEPTA runs 44 trains per hour through its four track tunnel at rush hour while the MBTA peaks at 32 trains combined on 22 tracks at North and South stations.)

The relevant issue, however, is how silly it is to build large rail yards on prime real estate in order to not run service!

The supposed “need” for this whole facility could be obviated simply by running more trains in service in the midday. (Some layover space could be built between Cambridge and Everett streets in Allston without impacting transit operations and development of the Beacon Park Yards.) If you have more trains in service, you don’t need storage for them. Considering that 75% of the costs of running Commuter Rail in Massachusetts are fixed, much of the marginal cost of providing increased service would be made up for by the opportunity cost of not building such an unnecessary facility. Most every other major Commuter Rail line runs more frequent midday service than the MBTA, even on lines to major anchor cities like Worcester, Providence and Brockton. In English: you have the trains, and the track, and the stations. Just run more darned trains already!

With that said, you still need to figure out where to run these darned trains. Obviously, increasing service on current lines to large cities and “Gateway Cities” makes sense. But there’s actually a way to increase service to Western Massachusetts without any major investment in track, stations or additional equipment. Right now, several train sets begin and end their day in Worcester. These trains could, instead, begin their trips further west, providing service to Springfield the Pioneer Valley.

The Commonwealth and Feds recently spent $83 million to upgrade the Connecticut River Line for passenger service, and the Boston and Albany main line already hosts Amtrak trains (albeit at a pitiful top speed of 59 mph). So you might as well get some use out of it! There is a vague plan to provide commuter service in the Pioneer Valley soon linking Greenfield, Northampton, Holyoke and Springfield, and connecting with upgraded Springfield-Hartford-New Haven “Knowledge Corridor” service. Service couldn’t start overnight, steps would include working out a track use agreement with CSX and qualifying crews west of Worcester. But the track (with the exception of layover facilities in Greenfield; I assume trains could be stored overnight on tracks in Springfield’s station), stations (with the exception of Palmer where you might want to build a new station) and trains are in place. It’s not a big leap to running service.

Here’s what a schedule would look like for the trips serving Boston, Springfield and Greenfield. Train numbers are shown for current Amtrak or MBTA Commuter Rail service, and use current travel times, although the Boston and Albany ran two-hour Springfield-to-Boston schedules in 1950 with stops in Palmer, Worcester, Framingham and Newtonville. (Amtrak 448/449 is the Lake Shore Limited to and from Chicago via Albany, 55/56 is the Vermonter from Saint Albans to Washington D.C.)

| Eastbound | |||||

| Train # → | MBTA 508 | MBTA 552 | NEW | AMTK 56 | AMTK 449 |

| Dep Greenfield | — | 5:45 | — | 13:36 | — |

| Dep Springfield | 5:45 | 6:45 | 13:00 | 14:35 | 17:33 |

| Arr Boston | 8:20 | 9:07 | 15:20 | — | 20:01 |

| Westbound | |||||

| Train # → | NEW | AMTK 448 | AMTK 55 | MBTA 521 | MBTA 551 |

| Dep Boston | 9:38 | 12:50 | — | 17:05 | 19:35 |

| Arr Springfield | 12:00 | 15:18 | 15:15 | 19:35 | 22:00 |

| Arr Greenfield | — | — | 16:15 | — | 23:00 |

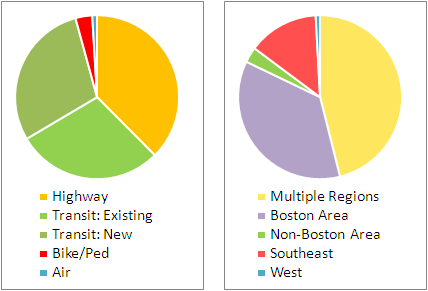

Rightly or not, Western Mass often feels like it gets the short end of the bargain when it comes to transportation funding. There has been hundreds of millions of dollars spent on infrastructure (most notably the Knowledge Corridor and Springfield Union Station), yet very little service to show for it. This mistake would be compounded by overbuilding layover facilities in Boston and siloing operations in Eastern and Western Massachusetts. Any passenger movements would need to accommodate CSX freight traffic between Worcester and Springfield, and in the long term, much more increased service may require a larger investment to re-double track the B&A line to Springfield (and to increase line speed where possible as well).

In any case, rail service in Massachusetts has long been focused on Boston, with a minimal statewide transportation plan (well, beyond taking donations from Peter Pan, buying them buses and having them get stuck in traffic on the Pike). The state has taken hundreds of millions of Federal dollars (and local match) to upgrade the line in the Pioneer Valley, but it barely runs any service. It would be a politically wise move to better serve Western Mass and, given traffic and tolls, would probably attract significant ridership, too.