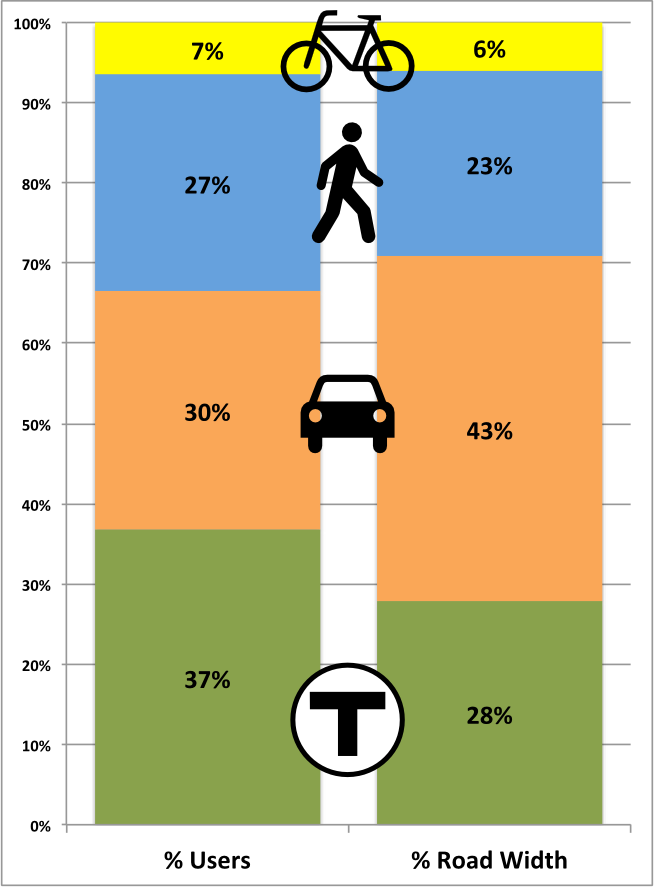

We’ve been covering Commonwealth Avenue a lot recently on this page, and here’s another post (likely not the last). In the last couple of days we’ve seen the Boston Globe editorialize that the current design is subpar, which, despite the supposed end of print media, is a decently big deal. This post will be somewhat short on words, but I think get across an important point: the current design gives drivers more room than they deserve, and gives the short shrift to everyone else: transit users, bicyclists and pedestrians. Many thanks to TransitMatters for digging through the BU transportation plan (several hundred pages, including the entire MBTA Blue Book appended to the end) and finding their peak hour traffic counts. He presented it as a table, I simplified it a bit (grouping all transit riders) and show it to the right.

Tag Archives: bike lanes

The next step on the BU Bridge area for bikes

The City of Boston recently made somewhat dramatic improvements to the bicycle facilities along Commonwealth Avenue. The formerly orphaned bike lane has been restriped through the intersection, and the new paint is all bright green. In addition, there are reflectors in the road to the right of the lane which I can attest are very visible from a vehicle at night. It’s a good start.

Meanwhile, Brookline has installed contraflow bike lanes on Essex Street to allow cyclists to go from Essex to Ivy to Carlton and allow a low-traffic alternative to get from the BU Bridge to the Longwood area. (And for those of us headed to Coolidge Corner, another block before we take a right.) Going towards the bridge, the town has striped in a bike lane. And, more importantly, they’ve cut a “bicycle crosswalk” across the BU Bridge loop (Mountfort Street) to allow cyclists to get from the Brookline streets to the BU Bridge without having to cross medians, loop around through the intersection of death, or ride the sidewalk to the light. It also allows cyclists coming from Brookline to skip Commonwealth altogether, a great boon to cyclists who don’t want to ride one of Boston’s widest and busiest streets. So, what was once a death trap for cyclists—and is still rather cumbersome—is getting better. (The picture at right shows the bike lane in the foreground and the crossover in the background.) There is some background information in this document.

The next step, I think, is to better allow cyclists coming from the west on Commonwealth and headed towards Cambridge, would be a two-stage bike turn box. This is not a new concept—it even exists in Boston—and goes as follows:

- An eastbound cyclist on Commonwealth approaches the BU Bridge.

- The cyclists, upon a green light, goes through the light, then pulls in to a separate line to the right of the bike lane and turns their bike towards the bridge.

- Once the light changes, the cyclist pedals straight across and in to the bike lane on the bridge.

Longfellow Bike Count

One of the issues I’ve touched on in the Longfellow Bridge series is the fact that there as no bicycle count done at peak use times—inbound in the morning. The state’s report from 2011 (PDF) counted bicyclists in the evening, and shows only about 100 cyclists crossing the bridge in two hours. Anecdotally, I know it’s way more than that. At peak times, when 10 to 20 cyclists jam up the bike lane at each light cycle, it means that 250 to 500 or more cyclists are crossing the bridge each hour. So these numbers, and bridge plans based on them, make me angry.

But instead of getting mad, I got even. I did my own guerrilla traffic count. On Wednesday morning, when it was about 60 degrees and sunny, I went out with a computer, six hours of battery life and an Excel spreadsheet and started entering data. For every vehicle or person—bike, train, pedestrian and car—I typed a key, created a timestamp, and got 2250 data points from 7:20 to 9:20 a.m. Why 7:20 to 9:20? Because I got there at 7:20 and wanted two hours of data. Pay me to do this and you’ll get less arbitrary times.

But I think it’s good data! First of all, the bikes. In two hours of counting, I counted 463 bicyclists crossing the Longfellow Bridge. That’s right, counting just inbound bicyclists, I saw more cyclists cross the Longfellow in one direction than any MassDOT survey saw in both directions. The peak single hour for cyclists was from 8:12 to 9:12, during which time 267 cyclists crossed the bridge—an average of one every 13.4 seconds. So, yes, cyclists have been undercounted in official counts.

Are we Market Street in San Francisco? Not yet. Of course, Market Street—also with transit in the center—is closed to cars. [Edit: Market Street is partially closed to private vehicles, with plans being discussed for further closures.] And at the bottom of a hill, it’s a catchment zone for pretty much everyone coming out of the heights. They measured 1000 bikes in an hour (with a digital sensor, wow!), but that was on Bike to Work Day; recent data show somewhat fewer cyclists (but still a lot).

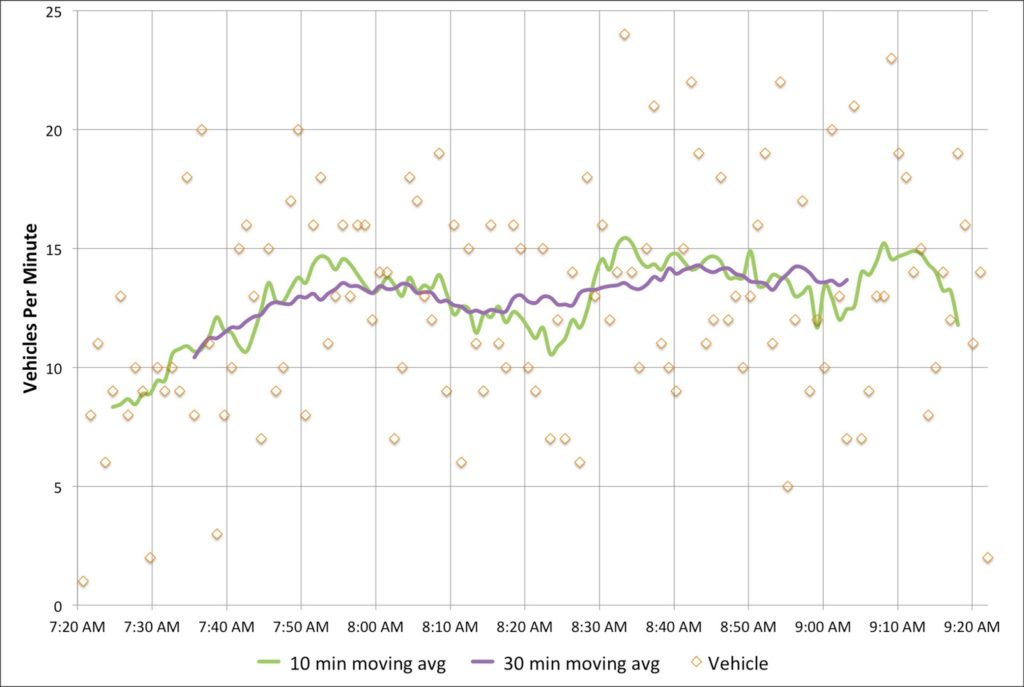

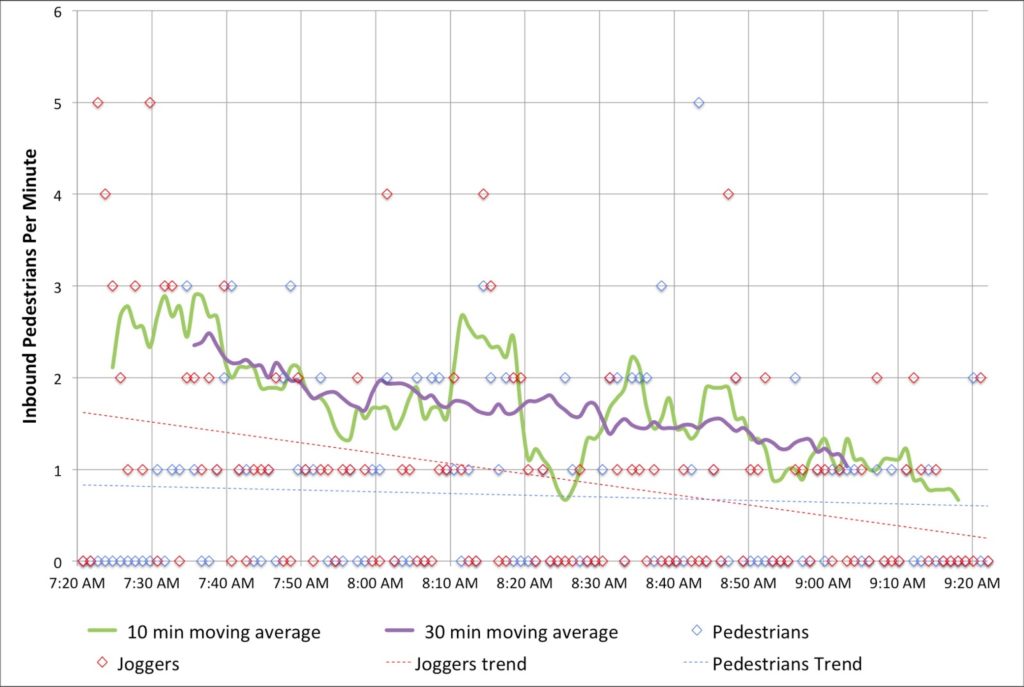

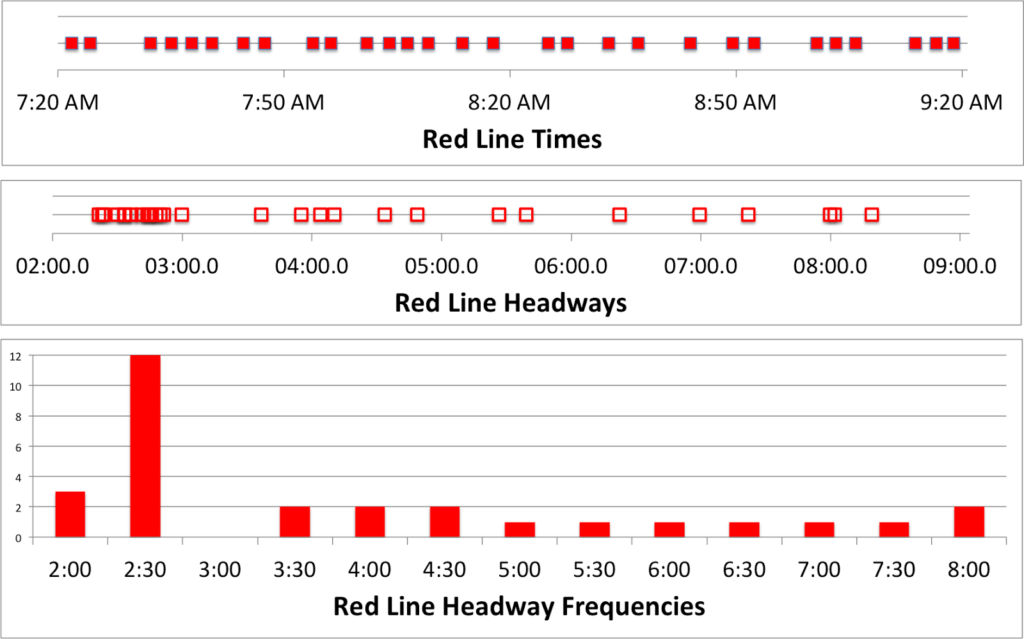

I also counted vehicles (1555 over two hours; 700 to 800 per hour, including three State Troopers and one VW with ribbons attached that passed by twice), inbound pedestrians (about 100, evenly split between joggers and walkers, although there were more joggers early on; I guess people had to get home, shower and go to work) and even inbound Red Line trains (30, with an average headway of 4:10 and a standard deviation of 1:50). I didn’t count outbound pedestrians, or the exact number of people I saw stopping to take pictures (at least three on my little nook of the bridge).

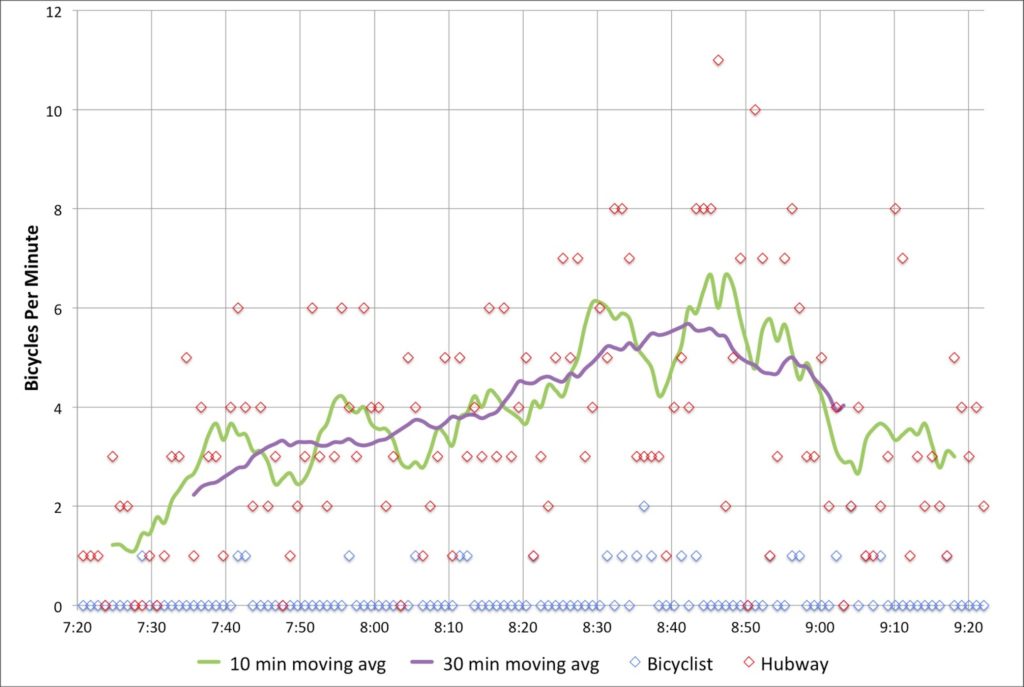

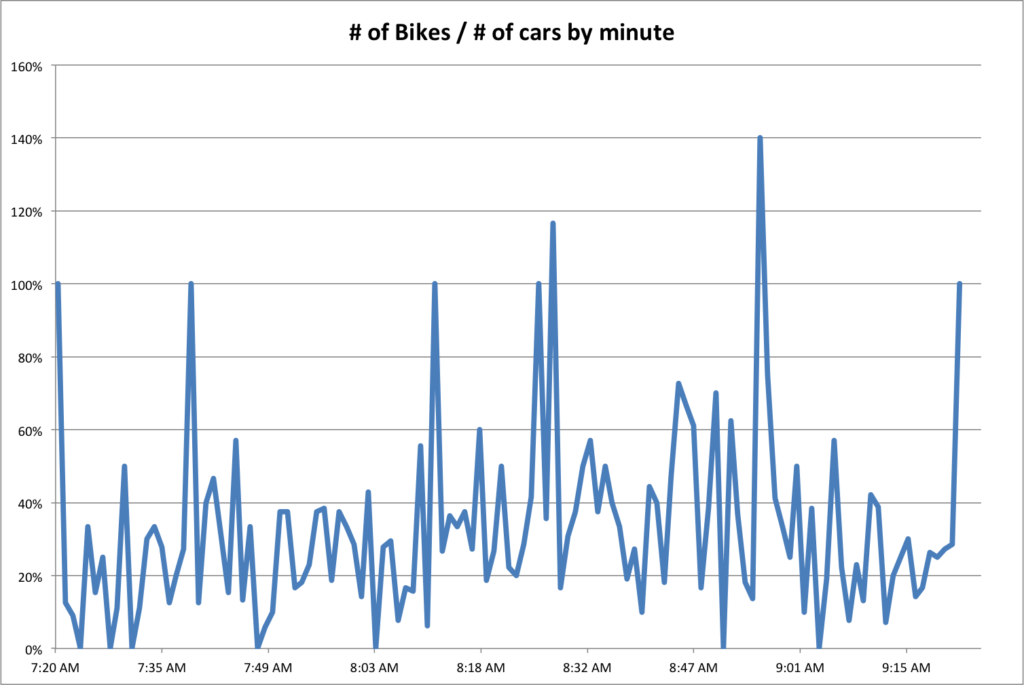

But did you come here for boring paragraphs? No, you came for charts! Yay charts! (Also, yay blogging at 11:20 p.m. when I should be fast asleep. Click to enlarge.)

First, bikes. Cyclists crossing the bridge started out somewhat slow—the moving average for the first 20 minutes was only one or two per minute. But the number of cyclists peaks around 8:40—people going in to the city for a 9:00 start—before tapering off after 9. I’ve written before about seeing up to 18 people in line at Charles Circle which is backed up by these data; the highest single minute saw 11 cyclists, and there were four consecutive minutes during which 36 bikes passed. At nearly 6 bikes per minute for the highest half hour, it equates to nearly 360 bikes per hour—or 10 per 100 second light cycle. Too bad we’re all squeezed in to that one little lane. (Oh, here’s a proposal to fix that.) If anything, these numbers might be low—the roads were still damp from the overnight rain early this morning.

What was interesting is how few Hubway bikes made it across the bridge—only 25, or about 6% of the total. With stations in Cambridge and Somerville, it seems like there is a large untapped market for Hubway commuters to come across the bridge. There are certainly enough bikes in Kendall for a small army to take in to town.

Next, cars. The official Longfellow traffic counts show about 700 cars per hour, which is right about what my data show. What’s interesting is that there are two peaks. One is right around 8:00, and a second is between 8:30 and 9:00. I wonder if this would smooth out over time, or if there is a pronounced difference in the vehicular use of the bridge during these times. In any case, 700 vehicles per minute is not enough that it would fill two lanes even to the top of the bridge, so the second lane—at this time of day, anyway—is not necessary on the Cambridge side.

I also tracked foot traffic. I did my best to discern joggers and runners from commuters. Joggers started out strong early, but dwindled in number, while commuters—in ties and with backpacks and briefcases—came by about once every minute. I was only counting inbound pedestrians, and there were assuredly more going out to Kendall. Additionally, I was on the subpar, very-narrow sidewalked side; the downstream sidewalk is twice the width (although both will be widened as part of the bridge reconstruction).

And I counted when the trains came by. In the time that 2500 bikes, pedestrians and cars crossed the bridge, 30 trains also did. Of course, these were each carrying 500 to 1200 people, so they probably accounted for 25,000 people across the bridge, ten times what the rest of the bridge carried. Efficiency! The train times are interesting. The average headway is 4:10, with a standard deviation of 1:58. However, about half of the headways are clustered between 2 and 3 minutes. That’s good! The problem is that the rest are spread out, anywhere from 3:30 to 8:30! Sixteen trains came between 7:20 and 8:20, but only 14 during the busier 8:20 to 9:20 timeframe. I wonder if this is due to crowding, or just due to poor dispatch—or a combination of both.

In any case, what Red Line commuter hasn’t inexplicably sat on a stationary train climbing the Longfellow out of Kendall? Well, after watching for two hours, I have an answer for why this happens! It is—uh—I was lying. I have no idea. But I say no fewer than a half dozen trains sit at that signal—and not only when there was a train just ahead—for a few seconds or even a couple infuriating minutes. I was glad I wasn’t aboard.

Finally, we can compare the number of bikes as a percentage of the number of cars crossing the bridge each minute. Overall, there were 30% as many bikes as cars. But seven minutes out of the two hours, there were more bikes across the bridge than vehicles. Cars—due to the traffic lights—tend to come in waves, so there’s more volatility. Although bikes travel in packs, too. Anyway, this doesn’t tell us much, it’s just a bunch of lines. But it’s fun.

Is a part-time bike lane appropriate for the Longfellow?

So far in our irregular series on the Longfellow Bridge we’ve looked at the difficulty accessing the bridge from the south, the usage of the bridge compared to the real estate for each use and how many bikes are actually using the bridge at morning rush. While my next step is to actually go out and count bikes (maybe this Thursday!), I’ve been thinking about what sort of better inbound bicycle infrastructure could be implemented for the bridge.

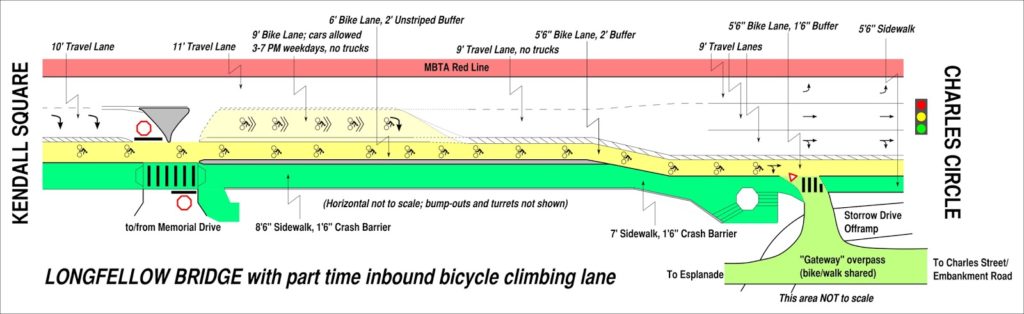

Here’s a graphic. I’ll make more sense of it below (Click to enlarge):

Here are the issues at hand:

- Peak bicycling occurs between 7:30 and 9:00 a.m., when bicyclists traveling from Cambridge, Somerville, Arlington and beyond converge on the Longfellow to commute to work in downtown Boston. For nearly any destination in Back Bay and Downtown, it is by far the easiest access.

- There is much less cycling outbound at rush hour because of mazes of one-way streets combined with heavy vehicular traffic on the other access roads (i.e. Cambridge Street).

- Thus, the highest bicycle use at any time on the bridge is during the morning rush hour inbound, but while plans indicate a wide, buffered bike lane going outbound, the inbound lane will barely be widened.

- Since the bridge has a noticeable incline from the Cambridge side, there is a wide spread of cyclist speeds, and it is reasonable to expect cyclists to want to overtake during heavier use times.

- With improvements to Beacon Street in Somerville as well as the access through Kendall Square, even more cyclists will crowd the bridge in the morning.

- With the expansion of Kendall Square and its reliance—to a degree—on bus shuttles, it can not be allowed to gridlock over the bridge during peak periods (generally evening rush hour).

Between Kendall Square and Memorial Drive, Main Street will merge from two lanes to one, to the left. The right lane will be for turns on to Memorial Drive only, and will be set off from straight-ahead traffic with bollards or a median.

Past the Memorial drive ramps:

The left inbound lane is kept at 11 feet and all non-Memorial traffic merges in to it before the bridge. The constriction for the Longfellow traffic is throughput at Charles Circle, so this shouldn’t dramatically affect traffic, especially since Memorial Drive traffic would exit in a dedicated lane. This will allow traffic to comfortably travel in it at all times. The lane would be signed as Vehicle Traffic, All Times. It would be separated from the right lane by an unusual marking such as a double broken white line.

The right inbound lane should be narrowed to 9 feet in width. Height restrictions (chains hanging from an overhead support) could be hung at intervals to discourage trucks and buses but signage would likely suffice. It would be signed as Bikes Only Except Weekdays 3 PM to 7 PM. No Trucks or Buses. It would be marked with diamonds or some other similar feature as well as “Sharrows” and separated from the bike lane by two solid white lines with no painted buffer in between, potentially with infrequent breaks.

The bike lane would be 6 feet wide and the two lines would serve as a 2 foot buffer at evening peak. It would be signed as a regular bike lane.

This will extend to the top of the bridge where the grade evens. Beyond that point, there is less need for a “climbing lane” for cyclists, and the bike lane will taper to one, buffered lane. The left lane stay 11 feet, and the right lane 9, but it will be open to cars at all times, with a continued buffered bike lane. Having the right lane closed to trucks and buses will dramatically increase the comfort level for bicyclists who are often squeezed by large vehicles, who will have no business in the right lane.

At the Cambridge End of the bridge, the merge to one lane before the Memorial Drive will funnel all Cambridge-origin traffic in to the left lane (this is the only origin for trucks and buses which can not fit under the Memorial Drive bridges). During non-peak afternoon hours, the Memorial Drive intersection would then join this traffic in a short merge lane after crossing the bicycle facility. At peak hours, it would continue in the right lane. This means that for a truck or bus to use the right lane, it would have to actively change lanes, meaning that even during rush hour, bicyclists would not be pinched by frequent tall tour buses and delivery vehicles. And at other times, most of the origin traffic from Cambridge would already be in the left lane, and only the Memorial Drive traffic—which already stops at a stop sign—would have to be signed in to the lane based on the time of day. The irregular lane markings will clue most drivers in to the fact that there is something different about the bridge, as will signage placed on the bridge approaches.

At the Boston end of the bridge, just before “salt/pepper shaker” the bridge could be widened (for instance, see this older image) to allow bicyclists to stay in a buffered bike lane and cars to sort in to three full (if narrow) lanes. However, two lanes might be preferable to allow trucks and buses to get from the left lane on to Charles Street (or such vehicles could be forbidden from this maneuver and forced straight on to Cambridge or left on to Embankment Road). In this case, enough room for side-by-side cycling in a bike lane—at least 7 or 8 feet—should be allowed (this is not showin the above schematic).

The potential for a flyover bike ramp to the unused portion of Embankment Road should not be discounted, either, as it would siphon much of the bicycle traffic away from the congested Charles Circle area. I called this the “Gateway Overpass” as a lower, gentler and wider bridge could span from the Embankment Road area across Storrow Drive to the Esplanade and allow easy egress to Charles Street across the Storrow offramp. The current bridge is narrow, steep and congested, and provides far more clearance over Storrow Drive than necessary. A new bridge is proposed (see page 10 of this PDF) but I think a level bicycle facility would be very helpful to help bikes avoid the congestion at Charles Circle.

If this project were found to be either dangerous for cyclists or a major impediment to traffic in Cambridge, it could be changed simply by restriping existing lanes, so there would be no major cost involved. If it constricted traffic enough, the lanes could be restriped with a buffer to allow a wider cycling facility inbound at all times.

I think it’s worth study, if not a try.

Longfellow Bike Traffic update

I came in this morning across the Longfellow. As I jockeyed for position through Kendall, I knew it was going to be busy on the bridge. I’ve seen ten bicycles per light cycle on the bridge, but today the lane was chock-a-block with bikes all the way across the bridge. With minimal auto traffic, faster cyclists were swinging in to the right lane and passing slower cyclists. And when we got to the bottom, well, it was quite a sight.

I came in this morning across the Longfellow. As I jockeyed for position through Kendall, I knew it was going to be busy on the bridge. I’ve seen ten bicycles per light cycle on the bridge, but today the lane was chock-a-block with bikes all the way across the bridge. With minimal auto traffic, faster cyclists were swinging in to the right lane and passing slower cyclists. And when we got to the bottom, well, it was quite a sight.

I quickly hopped the sidewalk to take a picture. By my quick count, there were 18 cyclists in line waiting for the light to change at the bottom of the bridge. Last month, I’d assumed 10 bicyclists per light cycle, which would equate to 360 per hour. At 18 bicyclists, this is an astounding 648 bicycles per hour, or one every six seconds. That’s nearly as many vehicles as use the entire bridge in the AM peak (707). And this is despite the fact that the Longfellow is a narrow and bumpy bicycle facility.

So it is a shame that the current plan for the bridge allocates just as much space to vehicles, and does not appreciably expand the inbound bicycle facility. As we crossed today there were few vehicles, but bicycles could barely fit in the lane. Since the bridge hasn’t been rebuilt yet, there is still time to advocate for fewer vehicle lanes (one lane expanding to two would be mostly adequate) and a much wider bike lane allowing for passing and a buffer.

The current bicycle counts are only for the evening commute where, as I’ve pointed out before, it’s much harder to get to the Longfellow due to traffic, topography and one-way streets. I think it’s high time for a peak morning bike count on the Longfellow. And time to suggest to MassDOT they reexamine the user base for the roadway before it gets reconstructed and restriped.

Plus, if we have 650 bikes per hour using the current, subpar facility, imagine the bike traffic once the lane is wider and well-paved. To infinity and beyond! Or, at least, to 1000.

A word on road salt

|

| That’s not snow. (Boylston Street south of Boston Common) |

There’s been some grief on the Internet and the Twitterverse about the heaps of road salt thrown about the roads in Boston in the last couple of days. What happened—I think—is that several inches of snow were predicted (albeit with a lot of doubt if you actually read the forecast discussion) and the city preemptively salted the roads. No snow fell, the salt got ground up, and high winds wafted it in to the air. It’s pretty gross. And it’s really bad for your bike.

Yes, Massachusetts oversalts and overplows. A moderate snowstorm on a Sunday morning will see thousands of plows fanned out across the state. I’ve driven during a storm and seen phalanxes of 10 plows stretched across three lanes, scraping the road clean from side to side, even though there wasn’t that much to push off. Cities take a bit longer, but they generally get the roads clean. And they salt the hell out of the roads, apparently. Every guy with a landscaping truck has a state plow contract, and by golly they’ll get them roads down to pavement. Even if they already are.

But then there’s Minnesota. Unless there is heavy snow, they don’t touch the roads. A few inches? It will get blown off after a while. If it’s cold, that’s the case, and salt won’t do much good. But when there’s more snow, and it’s warmer, it gets compressed and if temperatures then fall it freezes solid. If there is heavy snow, there are not enough plows to go around, and roads don’t get cleared as quickly as they should. And in the cities? They plow the day after the storm, and don’t even bother to push the snow off of corners, so what they’re really doing is plowing powder off the previously compressed snow leaving ridges of ice all winter on every side street. You have to move your car so they can plow to the curb on all streets, but by the time everyone has moved their cars there’s compressed snow all over the place. If it’s -5 by the time the plows come around, they don’t do too much good.

They also don’t salt pretty much ever. Sometimes it’s too cold, but sometimes a couple inches of snow falls, melts a little, turns to a sheet of ice and then freezes, at which point the streets are skating rinks. There is an issue of lakes becoming saltier—which is less of an issue in Boston where most runoff finds its way in to the already-salty ocean—but judicious use of road salt when it’s needed would be nice.

I’m sure there’s a happy medium between these approaches. If anything, maybe in Boston we can get them to not salt the roads until it actually snows. And, good golly, the sidewalks.

Chinatown to Charles: the Bermuda Triangle for bikes in Boston

When I bike to work, my route is simple. I head down Main Street in Cambridge, cross the Longfellow Bridge, and take a right on to Charles Street. I go diagonally across Beacon Street on to the Common, bike down the wide bike path there, and then bike half a block (or, if I’m on a Hubway, a whole block), slowly, down a sidewalk to the office. It’s simple, relatively safe and even pretty fast.

On the way home, I don’t even bother to try the reverse. It is damn near impossible to get from the Chinatown/Theater District/Park Square area to the Longfellow Bridge, and the options are dangerous and annoying enough that I wind up on the Commonwealth Avenue bike lanes to the Harvard Bridge to Cambridge, a less direct, but much safer route. As such the inbound and outbound portions of my ride are, except for half a block of Mass Ave in Cambridge, completely different.

But what about when I have to go to Kendall? There are several options for getting to the Longfellow, each of which has some major bikeability issue. The main issue is that Charles Street is one way, with no provision for cyclists going northbound. It’s sidewalks are narrow and riding contraflow is a death wish (oh, and it’s illegal). Beacon Hill—the neighborhood it traverses—is comprised of one-lane, one-way roads, and they have been signed in such a way as to prohibit through traffic, which is sensible since it was laid out way, way before cars were invented. This would be fine, but there is no parallel to Charles Street. To the east is Storrow Drive. To the west is Beacon Hill. There’s no good way to get the third of a mile from the Common to Charles Circle.

I’ve gone through the options (none of them good) and rated each from 1-5 for three categories: bike-car safety (how safe is it in spaces shared with cars?), bike-ped safety (how safe is it on spaces shared with pedestrians?) and bikeability (is it really annoying to bike?):

The Storrow double-cross is what you get if you ask Google Maps. It’s a pretty bad suggestion. The two crossings are coded as bike lanes, and while they do provide traffic-free crossings of Storrow Drive, neither is bike friendly, at all. To get to the bridges, you first have to cross four lanes of traffic on Charles Street, without the benefit of lights, unless you dismount and use crosswalks at the corner of Charles and Beacon. The path on the north side of the Public Garden is not bikeable. I call this the Beacon Weave. It’s not much fun on a bike.

And all that does is get you to the bridges. The first crossing (1) is the Fiedler Bridge near the Hatch Shell. To gain altitude, it has two hairpin turns on each approach, the bottom of which is completely blind. Biking at a walking pace, or walking altogether, is necessary going up and down this bridge, which often has heavy foot traffic. Assuming you navigate that bridge, you get a couple hundred yards of easy riding before you have to navigate another double-hairpin bridge (2) to get back across Storrow. This one is less blind than the Fiedler, but it’s narrower and just as trafficked. Even then, that only gets you to the far side of Charles Circle, where you have to jockey in traffic turning off of the Longfellow and on to Storrow before you can get to the bike-laned regions on the bridge itself. This require four separate crosswalks or some creative light-running.

This route would be a bit more doable if there were a path from the river bike path to the Longfellow. But there’s not. It’s pretty nasty.

Verdict:

Bike-car safety: 3

Bike-ped safety: 1

Bikeability: 0

Grand total: 4

The Beacon Hill Stumble-Bumble is probably the most direct route, but it fails for a variety of reasons. Mainly, it involves going down several one-way streets the wrong way, which causes Google Maps to say things like “walk your bike” in the directions more than once. Plus, these streets are steep, narrow and have blind corners. It might be fun if you are a bike messenger, but if you value your life, it’s a pretty bad option. If a car comes the other direction, there is not enough room to pass with any degree of comfort and safety. And the streets are designed to not let you through, so if you don’t know your way, you’ll wind up lost and spit out on to Charles, Beacon or Cambridge Street anyway.

Verdict:

Bike-car safety: 1

Bike-ped safety: 2

Bikeability: 0

Grand Total: 4

The Beacon Hill Crossover is another Google Maps suggestion, and it’s slightly better than the first. It has you cut across the Common (or you can go around on Beacon), climb Beacon Hill, and descend on Bowdoin Street. That part of the route, aside from the hill climb, is not too bad. Then you hit Cambridge Street. Outside of rush hour, this isn’t that bad. During rush hour, this backs up off of Storrow Drive, and to get to the Longfellow you have to slalom slow-moving cars, and then get through the intersection at Storrow. There, it behooves you to find the left-most lane, because most of the traffic is turning right on to Storrow with no idea that a bicyclist might be going straight. Charles Circle is bike no-man’s-land (no-bike’s-land?) and it is several heartbeats before you are in the relative safety of the bike lane on the bridge. Oh, and there are always hordes of pedestrians running across Charles Circle to get to the T stop. A variant of this route via the less-hilly but longer and more-pedestrian-mall Downtown Crossing, which scores similarly, is shown as well.

Verdict:

Bike-car safety: 1

Bike-ped safety: 1

Bikeability: 3

Grand Total: 5

The Storrow Shortcut is the route I actually use. It isn’t pretty, but it certainly gets the job done. The main issue is that it requires either biking a narrow, decaying sidewalk along Storrow Drive or, more comfortably, actually biking down Storrow Drive itself! Google doesn’t realize that Storrow is not officially closed to bikes, and that there is a sidewalk along that route, so I can only show this route in driving directions. And, no, it’s not as crazy as it sounds.

On the few hundred yards of Storrow I bike, the road is three lanes wide and it has a narrow-but-painted shoulder line. It’s definitely better than the rutted-and-cracked sidewalk. Traffic is usually very slow there in the afternoon, and I can usually glide past the gridlock for the couple of blocks up towards the T stop. Once there, I hop on to the sidewalk and the unused part of Embankment Road and then under the bridge before hooking a left towards Cambridge. It avoids one-ways the wrong way, it misses the thick of the pedestrians, and it requires a minimum amount of weaving through traffic (but doesn’t miss the Beacon Street Weave). It’s ugly, but it works.

Verdict:

Bike-car safety: 1

Bike-ped safety: 4

Bikeability: 2

Grand Total: 7

All of this, of course, could be solved with a two-way cycle track on Charles. This has been proposed, but has not seen any steps taken towards actual construction. Charles is three lanes of traffic and parking on both sides. Its shops are mostly pedestrian-oriented, and it probably doesn’t need this parking, but taking it out would cause an uproar. However, the street would, and should, function perfectly well with two lanes. And such a lane would funnel Cambridge-bound traffic from the Back Bay across the Theater District and Chinatown to the Financial District and even the Seaport. It would be well used.

Poor sharrow/pothole placement

I was biking up to Arlinton to check out the black raspberries along the Minuteman Rail Trail (sadly, there are many fewer than a few years ago when I cleared several pints) and was biking up North Harvard Street in Allston towards Harvard Square. I’ve biked this route frequently in recent months, and it’s a very convenient way to get from Brookline to Cambridge. It’s always faster than the 66 bus (I love the 66, but … walking is often faster than the 66) and usually faster than driving since there are delightful bike lanes to slide by traffic in several locations of Harvard Street. And there’s always traffic on Harvard Street.

Anyhow, I was approaching Western Avenue and there was a truck straddling both lanes, so I cut him a wide berth and aimed over the “sharrow” (the road marking of a bicycle and double-chevron) as I slowed towards the intersection. Since I was braking, my weight shifted forwards, and I kept my eye on the truck to my left. All of the sudden, I was looking at the sky, and a second later, I was lying on the ground. In aiming at the sharrow I had inadvertently aimed directly into the six inch deep pothole it pointed directly at (see picture below), and since my weight was already shifted forwards I managed a full-on endo.

I realized I’d hit my head and would need a new helmet, and got up, shaken, but otherwise mostly unscathed. (My most recent bicycle acrobatics involved a swerve around a car pulling out of a parking space on Chestnut Hill Aveune—and in to the streetcar tracks. I came out of that one completely unscathed since I somehow stuck the landing and wound up running down the street as my bike skidded away.) I was shaking too much to ride my bike, but there was a bike shop a couple of blocks away and I went there to buy a new helmet (my current one was only five or six years old).

I settled down and managed to get back on my bike and return to the scene of the crime. Here’s a picture of the offending pothole:

The high sun angle doesn’t attest to its depth. It’s about six or eight inches deep and the perfect size to catch a bicycle wheel and flip a decelerating rider. Like me.

Just as impressive is the fate of my iPhone. I had it in my pocket—and thank goodness the back was facing out. It took a lot of the force, it seems:

The amazing thing is that it works perfectly! I put some packing tape over the shattered glass—which I’m sure absorbed a lot of energy—and it’s good as new. And a new back costs $12 and is pretty easy to replace, so I’ll get around to that. Until then, I have one badass iPhone.

So, I took a picture with it of my old helmet in the trash and the above pothole picture which I sent off to Boston’s bike czar (I have her email in my gmail) and she suggested I contact the mayor’s 24 hour hotline, which I did. We’ll see if the hole is patched; I’m biking that route at least weekly for the next month or so. I’ll be interested to see if there’s much response—it’s definitely a hazard to cyclists.

I am going to take off my amateur planner hat and put on my bicyclist hat (helmet?) to take away a couple of lessons from this adventure:

1. WEAR A HELMET. I am flabbergasted by the number of cyclists I see biking around the city without helmets. I know all the excuses, generally in the form of “I don’t need a helmet because …”

- I’m a good cyclist, I don’t need to worry. This is the stupidest one of all—most likely you are not going to be at fault for an accident. I can’t even begin to explain the inanity of this notion. I am a pretty good cyclist—I have thousands of miles of city riding under my belt—and I still have my share of mishaps.

- I’m not biking at night. This accident occurred around noon; the pothole would have been even more invisible filled with water.

- I don’t bike in bad weather. It was 85 and sunny.

- I don’t bike in heavy traffic. There was almost no traffic when I was out midday the week of July 4.

- I don’t ride fast. I was going about 8 mph when I hit this pothole.

- I don’t take chances or run red lights/stop signs. I was slowing down to stop at a red light and giving a wide berth to a truck.

- I don’t bike drunk. I was quite sober when I had my little flight here. As a matter of fact, I’ve never crashed drunk.

3. Watch the pavement. Even in the summer. Potholes happen.

(On a very slightly related note: the fact that, nearly 20 (!) years after it opened, there is no safe route through Arlington Center on the rail trail that doesn’t involve bricks and curb cuts is a travesty. How hard would it be to link the two sides of the bike path?)

In lane markings, paint does matter

I had a bit of a treat riding to work today: new paint for the bike lanes on Summit Avenue. Summit is the main east-west bike route west of downtown Saint Paul, extending from the top of the hill near the cathedral to the Mississippi. It is quite well-used, both by recreational cyclists and commuters, and is straight, relatively flat and in decent shape.

The lane markings weren’t disappearing completely (although notice the rather invisible bike stencil, which has not been repainted), but they were getting dull. I wish I had had my camera when they had painted only one of the lines anew; still, the new markings are very noticeable. And I believe it makes a difference. Drivers are more likely to notice the bike lanes, and more likely to look for cyclists; thus, cyclists are more likely to feel safe as they bike. And since a local cyclist was hit—and I saw him down moments later and am still surprised he was not badly hurt—when riding in one of these lanes by a turning vehicle, the more visibility, the better. In other words, well-painted lines will help drivers to look twice for bikes.

The lane markings weren’t disappearing completely (although notice the rather invisible bike stencil, which has not been repainted), but they were getting dull. I wish I had had my camera when they had painted only one of the lines anew; still, the new markings are very noticeable. And I believe it makes a difference. Drivers are more likely to notice the bike lanes, and more likely to look for cyclists; thus, cyclists are more likely to feel safe as they bike. And since a local cyclist was hit—and I saw him down moments later and am still surprised he was not badly hurt—when riding in one of these lanes by a turning vehicle, the more visibility, the better. In other words, well-painted lines will help drivers to look twice for bikes.

Now if they would only plow the lanes properly in the winter, and not let them become an icy mess.

[We’ll have a long post regarding segregated bike lanes soon]