Minneapolis and Saint Paul do not necessarily lend themselves to being a transit paradise. The core of the region is not particularly dense, and wide roads and a mostly-built freeway system make driving too easy. The tree-lined avenues of Minneapolis and Saint Paul are mostly lined by single-family homes and duplexes with sizable yards and alleyways, meaning that population densities are far less than the three-deckers of Boston, side-by-side bungalows of Chicago and row houses of DC, so there are fewer people to provide the necessary patronage for a dense network of frequent transit lines. The factors that push people to transit that define the urban experience in a Boston, New York or DC—heavy congestion and high parking costs—are, if not completely absent, less of an issue. And without many grade-separated lines, there are few cases where transit has a distinct time advantage over rush hour traffic.

Additionally, much of the area is pockmarked by both active and abandoned industry and transportation networks, further diluting the population (while, at the same time, providing significant potential for brownfield redevelopment). Most in-city residents live within a short walk of a bus line (the suburbs, for the most part, are less dense and even more car-dependent), but frequencies are often only every 20 or 30 minutes. Since the demise of the streetcar network (most car lines ran every 10 or 12 minutes or better, and streetcar ridership peaked at 238 million per year, triple transit ridership today) and the rise of the highways in the 1950s and 1960s, driving has just been to easy to compete with transit. Even at its peak, Minneapolis had just under 10,000 people per square mile, Saint Paul only 6,000; neither reached the peak density of large rust belt cities further east. (Both cities saw their populations bottom out in 1990 and have gained about 10% since.)

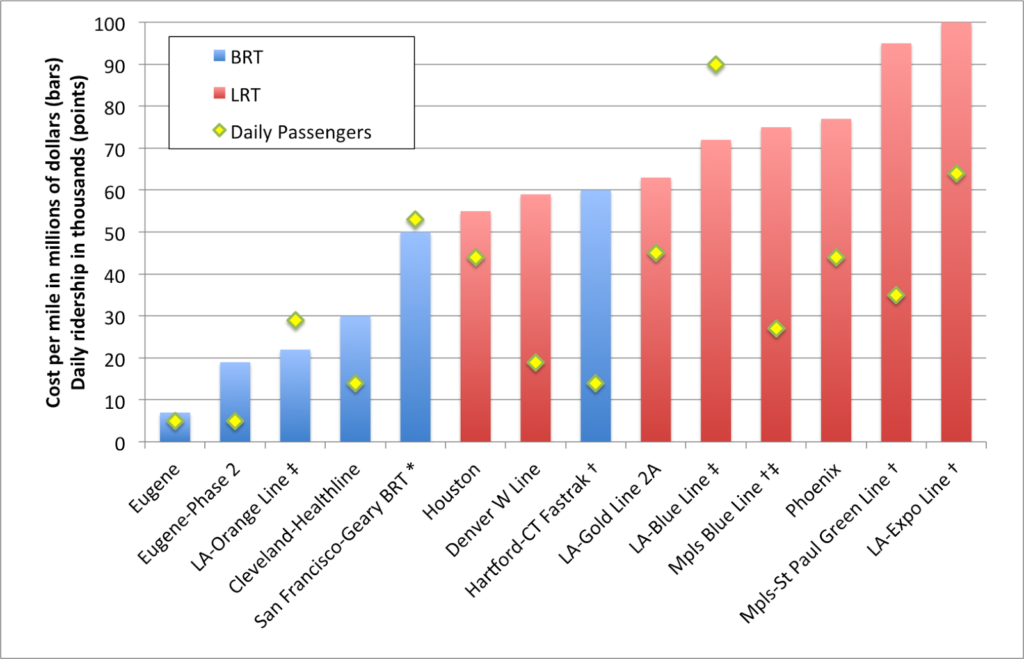

Minneapolis-Saint Paul was one of the largest cities without rail transit until its first line opened in 2004—a 12 mile line for a cost, in current dollars, $905 million (including two major elevated overpasses and a mile-long tunnel under the airport, despite exceeding initial estimates it is, in retrospect, quite cheap.)—and the second corridor, linking Minneapolis and Saint Paul, came online in 2014. These two corridors have, in their own right, made Minneapolis’s “Metro” the most heavily-used rail system to have been inaugurated since 2000 (since surpassed by Seattle’s Link, which is experiencing overcrowding with its recent extension), with more than 60,000 passengers per day. But there are two new smaller-scale developments which show that the Twin Cities are more forward-thinking in providing transit, and may well entice passengers out of cars while providing transit along corridors with high potential for redevelopment.

The first is the speeding up of the Green Line (formerly the Central Corridor) between Minneapolis and Saint Paul. When it first opened, the signal system of the line was not optimized for transit: trains often waited at cross streets for vehicular traffic despite the promise of transit signal priority. While the line is not perfected in the way that the Blue Line, which has gated, at-speed grade crossings, operates (and, running in the center of a city street, it likely never will be) the kinks are being worked out, and the promise of a 39-minute downtown-to-downtown ride is coming to fruition (the downtown sections are still quite slow and trains have minimal signal priority there). Speeds have also been improved, to 40 mph between most stations and 50 where there are no cross streets for long distances. (Note that this center-running light rail line runs faster than any MBTA subway or light rail service.) Further progress may be made, but the cities have not kowtowed to a few delayed drivers, and reaped both the operational efficiencies of running trains faster, as well as the potential for higher ridership. Trains run just every ten minutes, but with three 100-foot-long railcars, they have a capacity of more than 500 passengers each.

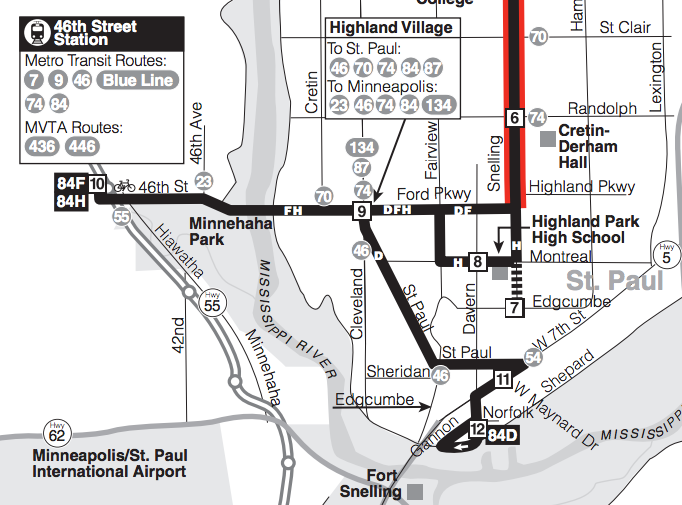

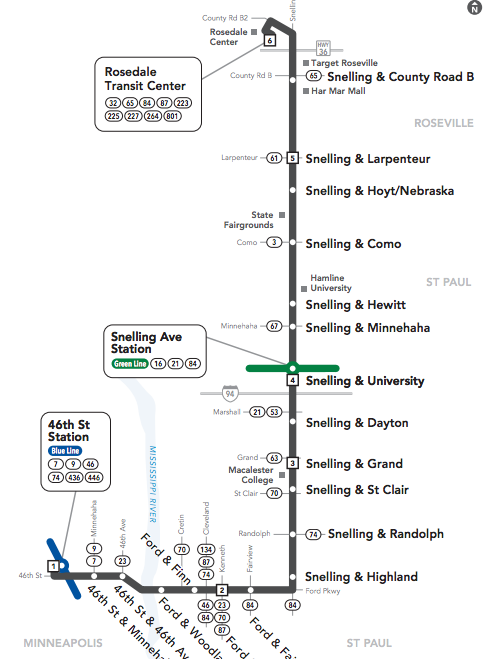

The second is the upcoming A Line bus rapid transit route in (mostly) Saint Paul. While not true BRT—there are few, if any, protected lanes, and the efficacy of transit signal priority will have to be tested—it’s the right steps towards getting more riders on to buses, and then on to trains beyond. The 84 has long been an important crosstown route running north-south between Minneapolis and Saint Paul. It connects the Green Line at Snelling Avenue with the Blue Line at 46th Street in Minneapolis, and with the rail lines has acted as a major feeder route to the two lines, albeit an urban bus route with frequent stops, often picking up just one or two passengers at each due to the density of the area, slowing down the route.

|

| The new A Line will eliminate the Montreal joggle, a vestige from the pre-light rail routing of the line. |

Beyond this, it has had its share of issues. It has long been a frequent route—every fifteen minutes for the trunk service—but service was downgraded in 2004 when the direct trip to the airport and Mall of America was severed and required a transfer to the Blue Line. Additionally, until recently, only every other trip made the airport run, meaning service to the rail line was only available every 30 minutes, a major transfer penalty, especially changing from rail to bus. The other branch of the route dead-ended at the 54 bus, which also ran to the airport, but with less frequency (every 15 minutes) and without the passenger amenities at the transfer point. Furthermore, the line had several twists and turns. Before 2004, it made several jogs through Saint Paul en route to the airport. In the past decade, most buses serving the light rail have detoured half a mile south of the straight east-west route to the rail transfer station, providing some additional coverage but adding several minutes of extra travel time to each trip. When there are few advantages to bus travel in the first place, once a route goes out of its way in this manner, driving becomes even more logical.

|

| No joggles! The new A Line will follow the city street grid: the most direct route. |

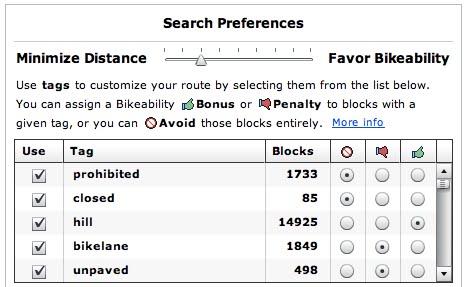

The new A Line BRT route will eliminate many of the factors which make driving more desirable in this corridor. First, stops will be consolidated, from eight or ten per mile to two or three, mostly at major nodes, bus transfers and “100% corners” which developed around these streetcar transfer points in the first half of the 20th century (the term has since been applied to highway interchanges in suburbia and transit transfer stations downtown). Each stop will be more developed, with heftier shelters with heating elements (important in Minnesota winters) and real-time departure information (important for everyone, but especially choice riders). Each station will have a fare machine and provide off-board fare collection, distinct vehicles with wider doors, and all-door, level boarding to minimize dwell times. Furthermore, buses will stop in the right travel lane, at a curb bump-out, so buses will not waste time pulling in and out of travel lanes. This will all enhance the speed of the route and the customer experience, and an analysis shows that it will bring many jobs closer to residents of the corridor.

Frequency will increase as well, with 10 minute headways matching headways of the light rail lines (frequency had been increased in 2014 to this level when the Blue Line opened, but not all buses ran to the Blue Line in Minneapolis), so transfers between the two lines will be minimal. Very importantly, these won’t just be rush-hour frequencies, but for midday service seven days per week (shoulder periods—before 6 a.m. weekdays, slightly later on weekends, and after 7:30 p.m. on weekdays and slightly later on weekends—will be somewhat less frequent, but still generally every 15 or 20 minutes). And the hodgepodge of coverage-based joggles will be eliminated: an every-half-hour 84 route will provide this coverage service, but the every-ten-minutes A Line will follow the grid to a T—or, as it happens, a backwards “L”—taking the most direct route possible. (The 84 will also provide service every block along Snelling Avenue, continuing a fallacy among many transit agencies that stops can not be consolidated at any cost. Thus some operational efficiencies will be lost by having empty buses running along the route, as nearly all passengers will opt for the faster and more frequent A Line. Even with stations every half mile along the Blue Line, MetroTransit still runs the 16 bus along the route, making these frequent stops. Based on limited observations, there are few, if any, riders, and it may behoove the agency to take whatever constituent hits are involved in putting this type of service out of its misery.)

|

| New stations feature curb bump-outs so buses board in regular traffic lanes. |

Is it perfect? Certainly not. Buses will still be susceptible to congestion, especially in the crowded Midway area, where exclusive bus lanes may be a future improvement. But it’s a major improvement, and for (relatively) minor dollars. Rather than a showy BRT or rail system (the corridor is probably not dense enough for rail, and doesn’t have the traffic issues that would require a full-on, expensive BRT system) the new A Line seems to address the most salient issues with a cost-benefit analysis, with low-cost, high-impact solutions (what they call Arterial BRT). It can also be incremental; if it’s successful, it will give the political capital to make further improvements, which may mean taking car travel lanes or parking spaces for queue jump lanes of exclusive bus facilities. It will leverage the much-improved Green Line light rail connecting to the downtowns with a better connection from the Snelling corridor, and the Blue Line at the other end. This system did not have free-falling ridership that would require a Houston-level redesign (bus ridership has grown in recent years, even as a major corridor—University Avenue—was replaced by light rail), but certain corridors—like the 84—did need improvement (others still do). This is a model which should be used for other high-use corridors in the Twin Cities (which is planned), and other systems in the US as well.

I started riding the 84 in 2002 (it still carried a note that it had been renamed from the Saint Paul 4—until 2000 Minneapolis and Saint Paul parochially had duplicate route numbers in different cities, like boroughs in New York) as a first year student at Macalester College, frequently to and from the airport. It ran every half hour, but with direct service it made the terminal impressively close: even with the joggles in the route, it was less than a 20 minute ride, door-to-door. The actually service degraded in 2004 with the rail transfer: it usually took about 30 or even 35 minutes, especially with the extra trip down to Montreal Avenue, and still only every half hour.

It took ten years, but a sensible route has finally been worked out. While the new service won’t match the speed of the pre-2004 service, with a more direct route, fewer stops and 10 minute headways for both the bus and the light rail, the trip, even with a transfer, should take about 25 minutes (with a perfect transfer at non-peak times, it may actually beat the circa-2004 20-minute mark), with the bus running up to 25% faster. Considering it will come three times as often, it will (finally) take full advantage of the light rail, and provide better service to the Snelling corridor in Saint Paul. Hopefully residents will notice the improvements and avail themselves of better transit options, even if it’s never perfectly competitive with an automobile.

Update: so far people are mostly happy with it, with one curmudgeon who won’t walk the extra block to a stop in the winter, supposedly. Update 2: Ridership on the corridor is up 25%.