A lot of hay is made about the “last mile” in public transport. Unless you live right at a bus stop or train station, your walk to the bus is going to be further than your walk to your car. (The term last mile derives from many other applications, such as communications and logistics, where the connections from end users to the main network are the least efficient, and thus most costly, to build and keep up. In transportation it relates to moving users from their origins and destinations to the nearest transit infrastructure.)

It’s an issue for car sharing, too. Even in the densest car sharing cities, many users live a few blocks away from the nearest shared car. (In these cities, of course, owning a car is generally very expensive and inconvenient, so the marginal gains from having a car right out your door are offset by the cost of a reserved spot or the time cost of circling the block looking for an unreserved one.) A car sharing network can be seen as similar to a transport network, with various access points spread across a region. With transport, the last mile is actually on both ends—getting from your origin to the network, and from the network to your destination—while with car sharing there is only an issue getting from your origin to the network as you then drive to your destination, so perhaps it’s more of a first mile issue. Still, it’s very similar—while there’s no hard research that I know of, anecdotal evidence is such that most car sharing users are willing to walk a quarter mile to a shared car, tolerant of maybe up to a half mile, but not very interested in going much further than that (similar to transit users).

Bike sharing may help to change that, by lengthening the distance people can travel to other modes. It fits in to a rather specific niche of the transportation network, for trips of between about 0.5 and 1.5 miles—trips that would be too short to bother with transit but too far to walk quickly. If bike share access is seamless and dependable—as is its goal—it can rather well fill this piece of the transport network. So before we look at how bike sharing and car sharing may interact, we should try to imagine where, exactly, bike sharing fits in.

In Europe, bike sharing has started up in the densest of cities—Paris (which is nearly as dense as Manhattan), Barcelona, Copenhagen—as well as many others. In North America, the first cities planning bike sharing systems are not necessarily the densest. Montreal, which is home to the successful Bixi system, is about as dense (11,000 persons per square mile) as Philly, although less-so than San Francisco (17,000) or Boston-Cambridge-Somerville (14,000). Boston is planning a system this year, as are considerably less-dense Minneapolis (7000) and Denver (4000), although, of course, the networks there will focus only on the densest portions of these cities. In a Paris, or even a Montreal or Boston, bike sharing will probably replace some trips made by transit or walking (or even short bike trips), but may not be as much of a driver of providing links to different modes, as transit is generally readily available. In the other cities, however, this may not hold true.

So there are basically two levels of cities implementing bike sharing. One is the dense city (>10,000 with a major fixed-guideway transit system and a large existing car sharing network: Boston, Montreal, Washington D.C., Paris, San Francisco …). The other is a less-dense city with a small fixed-guideway system and a fledgling car sharing system (Denver and Minneapolis, so far). Portland, which will likely join the bike sharing fray in the next couple of years, would fall in between, with its maturing transit system and a rather large car sharing market.

What bike sharing is best for are trips of a relatively finite distance, and it seems to vary based on the type of city (and which other transit modes are available). For trips significantly less than half a mile, you’d walk. The extra time it takes to get a bike and return it, even if there is a station right each end of a trip, is made up by the fact that by the time you got the bike, you’d be well on your way by foot. For trips longer than two miles, you’d likely want to ride your own bike (faster and more comfortable, but with a bit more overhead of storing a bike, carrying a lock and locking the bike) or ride transit (ditto, depending on the route), or use a shared vehicle. So bike sharing’s market is between about a third of a mile and a mile and a quarter (if you don’t mind locking your own bike) or a mile and a half (if you do)—perhaps a tad longer in cities without dense transit networks. Beyond that, biking, transit, a taxi or a car make sense.

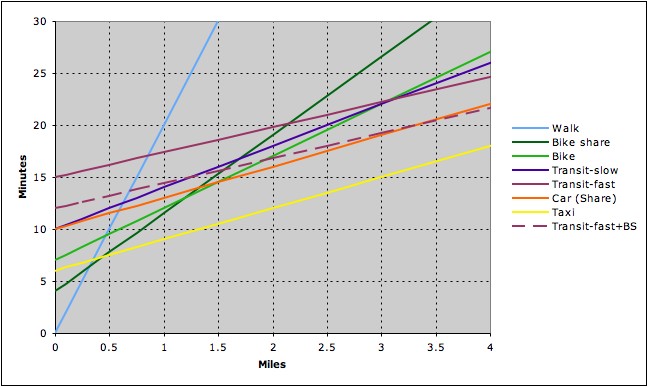

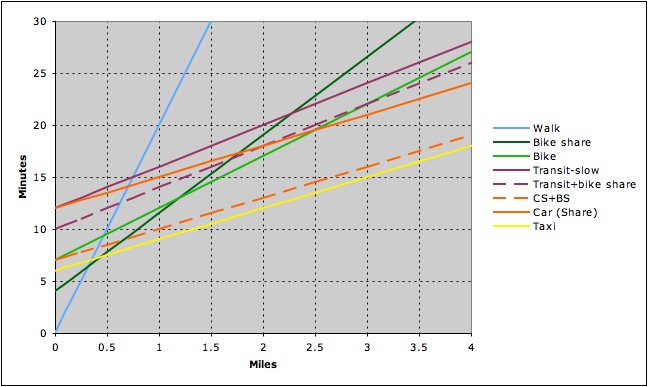

So, how does it break down. Well, I made the following assumptions:

| Denser city |

|

Less dense city |

| Mode |

MPH |

Overhead |

|

Mode |

MPH |

Overhead |

| Walk |

3 |

0 |

|

Walk |

3 |

0 |

| Bike share |

8 |

4 |

|

Bike share |

8 |

4 |

| Bike |

12 |

7 |

|

Bike |

12 |

7 |

| Transit-slow |

15 |

10 |

|

Transit-slow |

15 |

12 |

| Transit-fast |

25 |

15 |

|

Car share+BS |

20 |

7 |

| Car (Share) |

20 |

10 |

|

Car (Share) |

20 |

12 |

| Taxi |

20 |

6 |

|

Taxi |

20 |

6 |

| Trans-fast+BS |

25 |

12 |

|

Transit+BS |

15 |

10 |

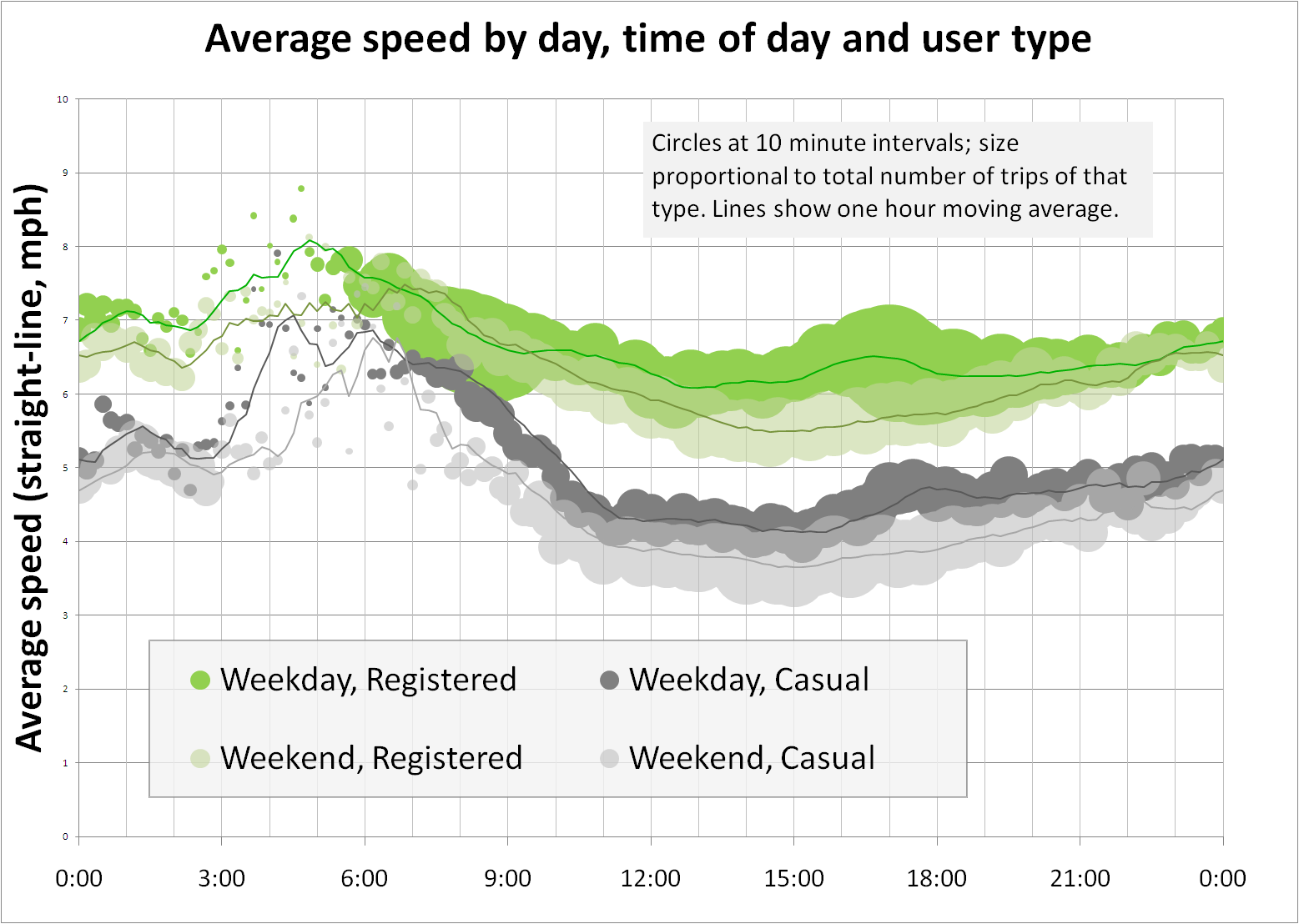

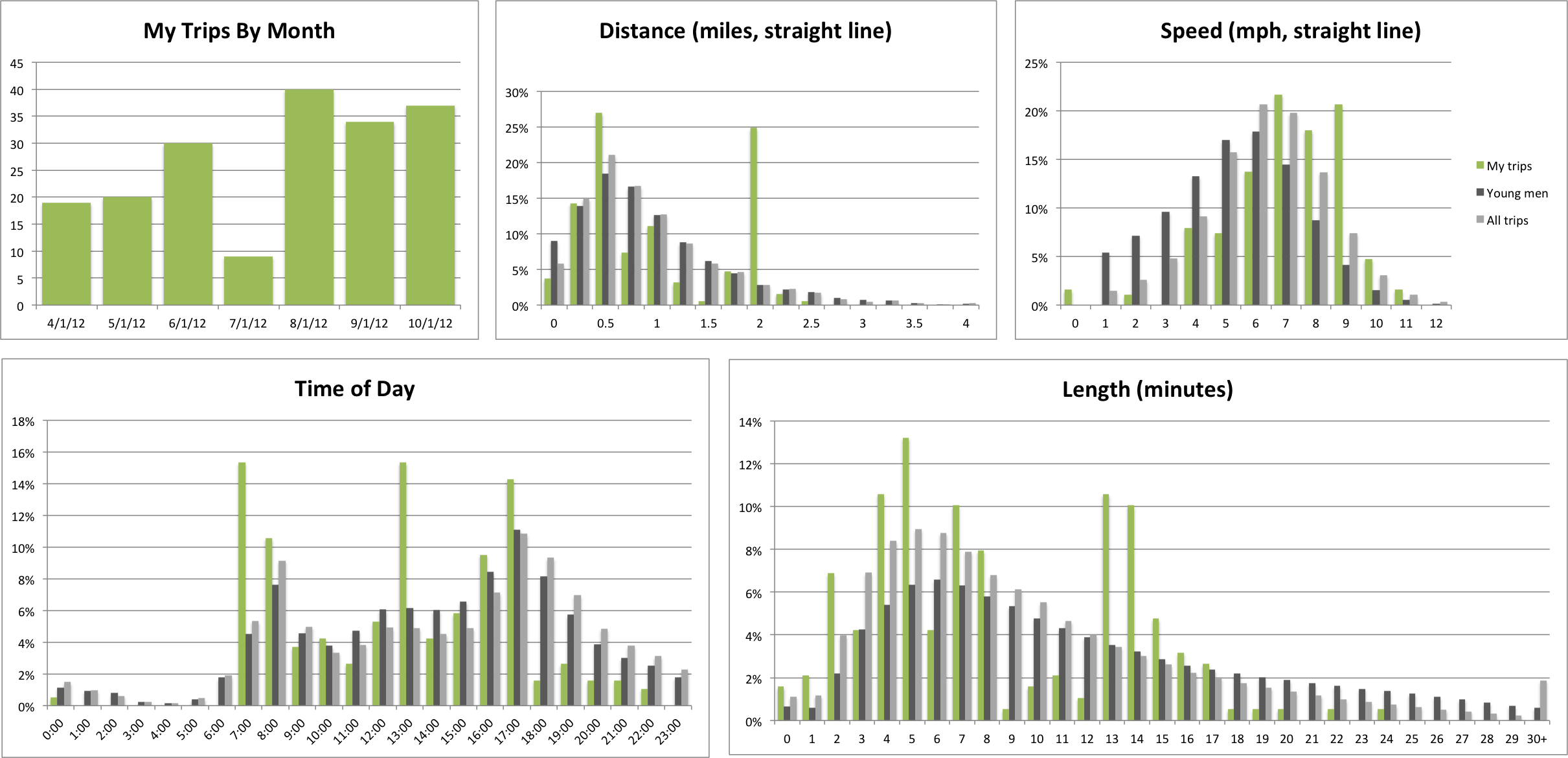

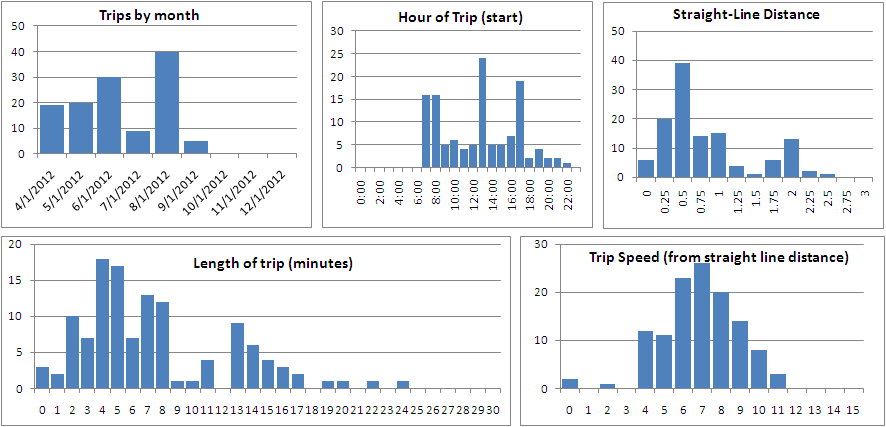

MPH is, of course, miles per hour once using that mode. Overhead is the amount of time it takes at the beginning and end of the trip to get to the mode from the origin and from the mode to the destination. Walking has zero overhead. Bike share was estimated to have four minutes (a minute to the kiosk and a minute getting the bike on either end; this is probably a lowball estimate). Biking seven minutes: three minutes to get your bike out of storage, two minutes to lock it at the end, and two for incidentals (shoes, helmet). Transit-slow is for local routes, which are probably a shorter walk, transit-fast for faster routes (such as a subway) which are generally further away. Car share overhead is to walk to the car and unlock it, and adding Bike share (BS) to a mode can cut down on the walking time.

Bike share only makes sense in multi-modal situations in a few scenarios:

- In denser cities, to access faster transit. For longer trips, riding a shared bike a mile to a faster transit mode (say, a subway instead of a bus line) can allow most of the trip to be at a faster speed, and make the overall trip faster. Since most, if not all, transit stations served by bike sharing will have kiosks, this makes sense. In addition, it may allow users to travel to another transit line of the same level of service and eliminate a transfer, but, to keep things simple, these models don’t really look at transfers.

- In less dense cities, car sharing, which is quite dense in large cities, is a bit more diffuse. Thus, many potential car sharers might live more than half a mile from the nearest shared car. In Minneapolis, every HOURCAR in the initial service area will be within about 100 feet of a bike sharing kiosk, so dropping off the car is easy, and it may allow people a bit further away to access the vehicles. And bike sharing is much easier, here, than riding your own bike because you don’t have to bring a lock and lock it up (and worry about it)

- In less dense cities with less dense transit networks, it may make sense for some people to use bike share to access slower transit routes, especially if they live far from a route with frequent service, although in areas served by bike sharing, route networks are rather well established.

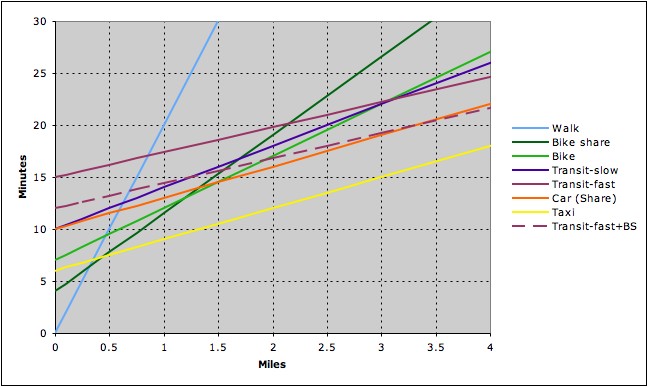

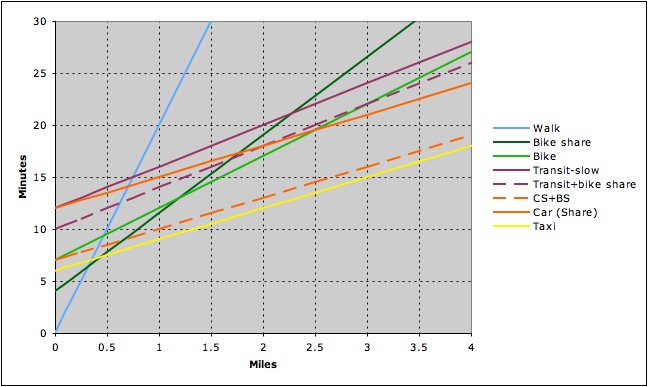

This perhaps, is best visualized by charts showing the time various trips take, based on the speed and overhead in the tables above.

The first chart is for denser cities, the second for less dense ones. For a given distance, the line nearest the bottom is the fastest mode. Cost is not taken in to account, but any orange or yellow line is a pay-per-use mode (taxi, car sharing) while any other line is a mode which is unlimited use, assuming most frequent transit and bike share users will have a monthly or yearly pass, so the marginal cost of each trip is zero. Dashed lines are variants of a mode with bike share added to the start or end of the trip to reduce overhead.

So in a dense city, where does bike sharing fit in to the picture? Well, assuming, for a minute, that we discount taxis (fast but expensive) and car sharing (expensive, fast, and not for short trips unless there is parking at the other end), bike sharing makes the most sense between about 1/3 miles and 1 mile if you have a bike of your own (or don’t mind locking said bike) and 1.5 miles if you would otherwise rely on transit. Considering that nearly half of trips are less than two miles from home, that’s a pretty big range—more tan a tad under half a mile and you’d walk, beyond two you’d take transit. However, bike sharing is generally only marginally faster than other options. Walking takes over for transit for trips much longer than 3/4 of a mile, so bike sharing will generally only ever save three to five minutes. So it better work well.

The other factor here is bike sharing and the faster transit network. What I mean by faster transit are generally grade-separated fixed-guideway modes (subway, proper light rail) but could also be express buses on highways. These lines are generally further apart than slower bus lines, so fewer people live within easy walking distance. In the chart above, for trips under three miles, it makes sense to take the bus (assuming it’s five minutes closer than the train), but if bike sharing can shave just a few minutes off the walk to the station, the train—which is more energy efficient and can more easily accommodate higher passenger loads—becomes a better option at distances of just over a mile—right about where bike sharing leaves off.

(Yes, it appears that bike sharing will actually make transit faster than driving at one point, but for very long distances, at least outside of rush hour, car sharing’s speed would be higher as drivers would access faster roads. This line should probably be curved (as should others) but that’s not really necessary for these simple simulations.)

In other words, imagine the following scenario: You live a block from a bus line, and the corner with the bus stop has a bike sharing kiosk. The bus line runs three miles to your office, or a store, or some such destination. You also live near a train station which has a line running to the same destination, but it’s a half mile walk from your house. Let’s assume that the bus and train have the same headways, that the bus runs at an average of 12 mph and the train at 25. Right now, your options are to walk to the corner, catch the bus, and ride 15 minutes to your destination; or walk ten minutes to the train, catch it and ride 7.2 minutes to your destination (17.2 total). With bike sharing, you can now ride at 8 mph 0.5 miles to the train (3.75 minutes), spend a minute at each end retrieving and returning the bike, and ride the 7.2 minutes, for a total of 12.95 minutes. So you save 2:03 versus the previous fastest mode time. It’s not a lot, but it’s a small advantage.

Of course, no transportation network is this cut and dry—but this is at least a way to imagine where bike sharing fits in. This summer, for instance, I wandered through Paris for a day with my family. We had two choices: the Metro or walking. Bike sharing was out because we didn’t have the proper credit card and my mother was scared of cycling through traffic without a helmet, and we didn’t know enough about the bus system to use it. (Taxis would have been an option, but they are expensive, slow—buses often have reserved lanes—and my family is cheap.) Had we had access to bike sharing, trips between half a mile and a mile and a half would have been easier and faster by Velib.

Now on to less dense cities. Here, the niche for bike sharing is similar, and maybe even larger, as we can assume that bus and transit service is a bit harder to come by. Bike sharing makes sense from about a third of a mile, but this time is only exceeded by transit for trips greater than two miles. (This is due to the assumption that frequent bus routes are a bit less prevalent in these cities; living right near a good bus route would obviously change this equation.)

But it also shows the other advantages of bike sharing in these cities. First, bike sharing increases the utility of transit. It’s not a big difference, but with a more dispersed route network, we can assume that bike sharing allows a few more residents to live within “easy travel distance” of said routes. (Although this may be confounded by most bike sharing locations being near bus lines.) If this is the case, it makes transit faster than bike sharing around 1.5 miles—if a shared bike is used to access the bus.

Then there’s car sharing. While cities like Boston and Montreal have robust car sharing networks, Minneapolis and Denver don’t. In Boston, for example, there are entire neighborhoods where every resident is within a half mile—or often less—of not one but many shared cars. This just isn’t the case with Minneapolis and Denver. If bike sharing can be utilized heavily in these cities—and without as much competing transit there is a bit more of a market to seize—it could be the missing link to shared cars. These data assume that the time needed to access a shared car would drop from twelve minutes (±1/2 mile walking at 3 mph plus a minute to access the car) to seven (±1/2 mile biking at 8 mph, plus two minutes to get and return the bike, a minute to walk to the bike and a minute to access the car).

If there are bike share locations in locations other than car sharing locations (as is the plan, at least, in Minneapolis), they will allow people who may live a mile from a shared car to get to the car in eight or ten minutes (biking) instead of 20 or 25. This is the proverbial “last mile.” In less dense cities with higher car ownership, it is not always possible to support a shared car on every block. We’ll see if this becomes the case, but it is possible that a symbiosis will develop between the two shared transportation modes where bike sharing will allow a substantial increase in the reach of the car sharing networks in Denver and Minneapolis.