Kendall Square is growing, but the road network around it is not, and traffic has mostly flat-lined (probably because, without a good highway network, only so many vehicles can enter the area). But as the planet burns and the region chokes on congestion, we ought to talk about how we can improve the area with less pavement and fewer cars. At the main transit node of Kendall Square, which has tens of thousands of transit riders and other pedestrians a day, the streetscape is mostly given over to automobiles, to the detriment of the vast majority of users. What could be a great, welcoming public space is instead a wide road with plenty of street parking, for no other reason than it’s always been that way. Its time for that to change: Kendall Square should be car-free.

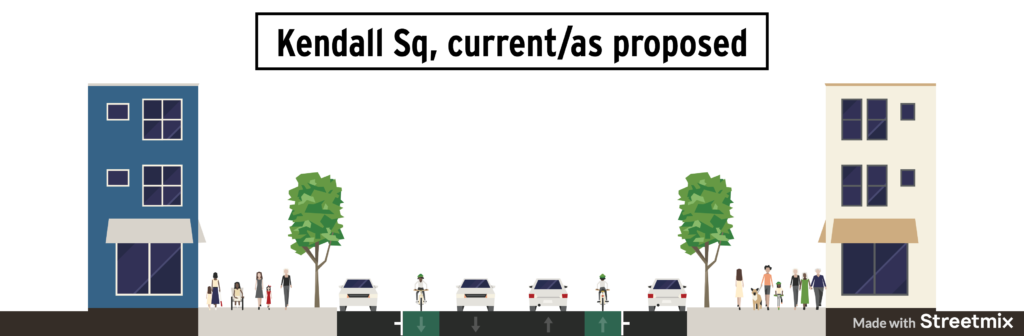

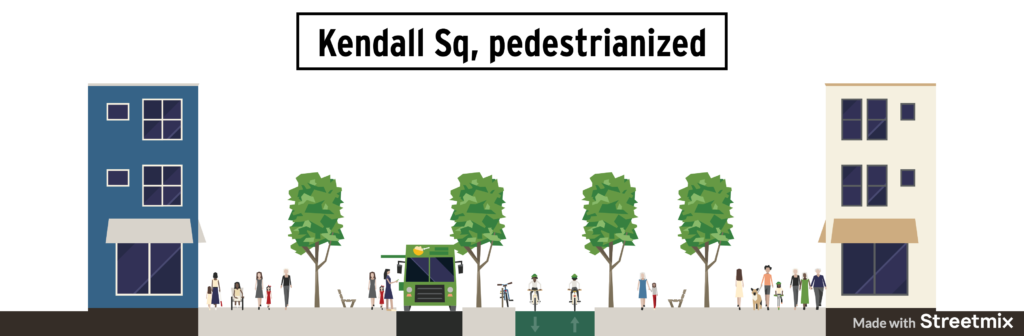

Which of these would you prefer to spend time in?

Unlike the Seaport, Kendall Square has been successful because of its access to transit, not in spite of it. There are no highways in to Kendall, so it has had to develop around transit access, while the Seaport has developed around the Turnpike extension, with the Silver Line mostly as an afterthought. As Kendall has grown it has become less of a desert than it was, especially as surface parking lots have been replaced by buildings or open space, and as more businesses have arrived, with a new grocery store opening recently.

Development has accelerated since 2016, especially along Main Street in the heart of the square, adjacent to the MBTA station. Until quite recently, this street epitomized the “suburban office park” feel of Kendall. Low-slung office buildings with ribbon windows wouldn’t be out of place in Bedford, Burlington or Billerica. The new MIT buildings add some spice to the square, casting off red brick for more modern designs. (In my opinion, they do this quite well, say what you will about the huge underground parking garage, the buildings, at least, are attractive. I only wish they were taller.) The four-story Coop building on top of the T, which was lifted straight from Waltham (it’s hard to cast too much blame, of course, because in the ’80s, everything was still moving out of the city, and it probably seemed deft to bring the suburbs to the city), has been torn down, and a taller, denser, and more-attractive building will take it’s place.

The road design 10 years ago was even worse. The median invited vehicle drivers to speed through the Square, and pedestrians were supposed to wait for a walk light at the T station to proceed across the intersection (although few waited, leading to conflicts with these speeding cars). This was replaced with a new design, but one which kept the street parking and travel lanes because even in Cambridge, we think about cars first (this came before protected bike lanes were prioritized, so the many bicyclists through the Square have to contend with pick ups, drop offs and cars darting in and out of the curb). The current design gives somewhat more priority to pedestrians, and the raised crossing significantly slows down vehicles, but even still, of the 90 feet between buildings on Main Street, the majority—50 feet—is handed over to those on four wheels.

So, Kendall has made progress, but not enough. We’ve taken the worst of the 1980s superimposition of the suburbs onto the city and begun to build out more of a viable urban space. For the past few years, and for the foreseeable future, Main Street has been home mostly to barricades, scaffolding and construction equipment. But once this disappears, Main Street in Kendall Square will still be far from what is desired: it’s a place to pass through, but not a place to linger. Mostly because when the new buildings go up, the road will return to its early-2010s design: through lanes for cars, unprotected bicycle lanes for drivers to open doors into and metered street parking.

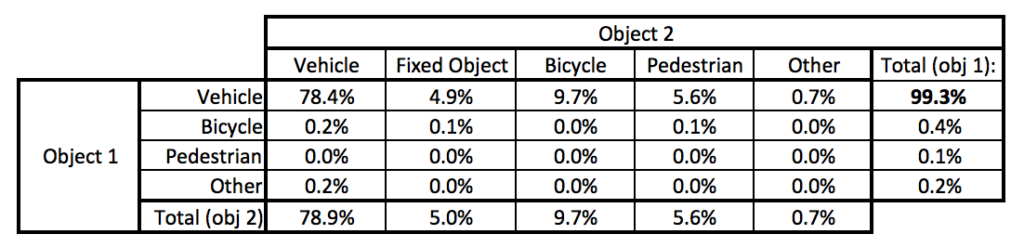

Cars are in the distinct minority in Kendall Square. Traffic counts show only about 5000 eastbound vehicles, and far fewer westbound since westbound traffic comes only from Third Street, not the Longfellow Bridge itself. Compare that to the Kendall Station, which has more than 15,000 boardings per day, meaning more than 30,000 people going in and out of the station. Add to that non-transit pedestrian trips and bicyclists and cars may only account for one tenth of the traffic in Kendall Square, especially once MIT’s SOMA project extends the campus into the square. Yet even after the current spate of construction, the plan for the road remains unchanged.

It’s time we change that.

There is no need for through traffic in Kendall Square. So we should get rid of through traffic in Kendall Square. Imagine if Kendall Square was a 500′-by-100′ pedestrian plaza. With benches, and trees. Maybe a water feature. Bike lanes? Yes. Bus lanes? Maybe. Car lanes? No.

Pedestrian malls have a somewhat fraught history, but recent examples in already-high pedestrian areas have been successful. As a means to revitalize an area, they have a mixed record, but in a vital area marred by traffic, (see much of Broadway in New York City), they can be quite successful. Thus, the failures often occur when there isn’t enough foot traffic to fill the space, but this is certainly not the case in Kendall. The new construction both in the Square and nearby development sites will add to the already tens of thousands of pedestrians using the space each day. MIT’s project will turn the square from a backwater of the campus lined with parking lots (some of them gravel!) to an entryway. There will be no shortage of pedestrians.

“But we can’t just take away travel lanes in Kendall Square!”

Nonsense. We already have. Broadway has gone from two lanes to one. So have both sides of the Longfellow Bridge (only partially thanks to yours truly), and a portion of Binney Street between Third and Land Blvd. So any traffic can easily be absorbed elsewhere. Binney Street, Broadway and Ames Street can distribute these vehicles to other paths of travel. As we saw with the Longfellow shutdown, any initial traffic tie-ups will dissipate as drivers choose other routes and, with safer infrastructure, other modes. And given the climate crisis globally and congestion crisis locally, making driving in Cambridge a bit more cumbersome is good: it makes people consider their many other options, and in Kendall, we have many.

Bikes would still be able to proceed through Kendall, with a two-way bicycle facility offset from the rest of the square. This could be designed with some sort of chicane system and speed calming, encouraging through cyclists to pedal at a reasonable speed for the environment and not treat it as the Tour de Kendall. Of course, ample bicycle parking would be provided. Coming west, cyclists would share a roadway with MIT delivery vehicles from Third Street; this roadway would act as a shared street or a woonerf, where any vehicles would be encouraged by the street’s design to proceed at a human pace, and couldn’t go much faster, since their only destination would be the MIT loading dock.

There is the question of what to do with the buses. Kendall is not a major transfer point, and the busiest route through the square, the CT2, has already been routed off of Main Street to a new stop on Ames. Three other routes—the 64, 68 and 85—terminate at Kendall, and more may be added as routes are realigned with the opening of the Green Line extension. One option would be to keep a single-lane busway through the square where the buses run today, allowing buses to serve the train station head house and layover, but this would eat into the potential gains in open space and walkability. A second, and I think preferable, option would be to have all buses terminate at the bus stop on Ames Street.

The parking on Ames Street adjacent to the new bike lane could be turned over to bus layover (because, again, why do need street parking everywhere in Kendall?). This would require somewhat longer transfers, up to 800 feet of walking from the inbound head house, but given that the CT2 and EZRide buses have moved out of the square with no ill effects, this may be a reasonable option, especially since most of it is through an covered concourse, and the rest would be through a pedestrian plaza. A new drop-off stop would be placed near Main Street, where arriving buses would drop passengers. There would then be space between this stop and the existing stop for buses to layover before their next trip, where they would pull forward to serve the stop.

A wide-enough corridor would be left along the southern side of the plaza for intermittent vehicular use. This would include things like major deliveries to buildings which could not be accommodated elsewhere and access for food trucks and farmers market vendors. It would also give the MBTA a path for buses during Red Line shutdowns, so that buses could still replace the Red Line when absolutely necessary between Boston and Kendall. But 99% of the time, Kendall would be car-free.

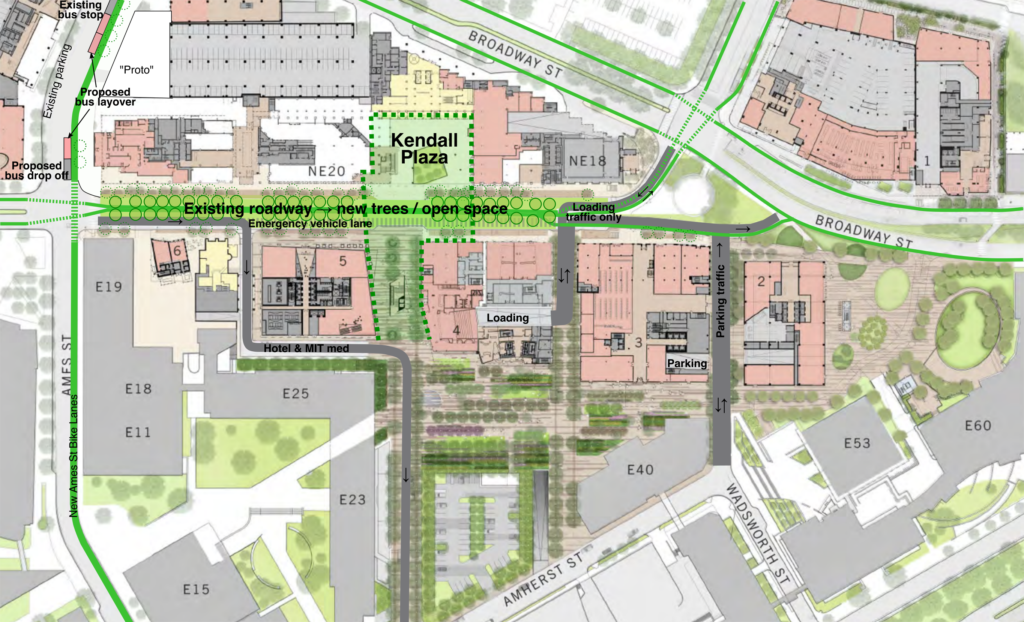

I’ve taken a plan drawing from MIT’s SOMA project and overlaid new open space as described. I’d suggest adding rows of trees to create an urban forest along the street itself, with an opening at the current crosswalk, creating a sight corridor and plaza feel through the square itself. I included a bicycle corridor (and other existing bicycle lanes), which would run between the trees, but would still leave most of the space in the square for pedestrians. I also show an emergency vehicle “lane” which would generally be a walking area, and assume there would be plenty of benches and tables in amongst the trees. I also show the bus terminal at the upper left. Gray areas show vehicular roadways on Main Street and in the rest of the SOMA area (other roadways are shown on the original plan). This is all a sketch, of course.

There would still be some asphalt in the square. From the west, a roadway would lead from Main Street to Dock Street, accessing the Kendall Hotel and continuing to MIT Medical. From the east, the planned loading dock in the SOMA project would be accessed from Third Street or Broadway, but this would be a shared street with limited, slow traffic. The parking entrance on Wadsworth Street would exit onto Broadway via Main Street, but the only entrance would be from Wadsworth and Amherst Streets (which would allow exiting traffic as well). Would this make driving somewhat less convenient for some drivers? Sure: someone headed to MIT’s SOMA parking would have to take a right on Ames, a left on Amherst and a left on Wadsworth instead of driving straight through Kendall Square.

This is a small price to pay for the tens of thousands of pedestrians would no longer have to avoid cars in Kendall. Maybe some drivers would take the train instead of driving. In the language of Kendall, this is a feature, not a bug.