In the fall of 2016, I took a course at MIT with Fred Salvucci (who also happens to be my research advisor here) called Urban Transportation Planning. Without knowing about my previous work on Central Square, the assignment arc for that semester was to critically analyze Mass Ave in Cambridge between Central Square and the Charles River and present findings to the City of Cambridge. When I emailed Fred and said “uh, just so you know, I sort of did this assignment already for my blog a few weeks ago” is response was something along the lines of “great, do more.”

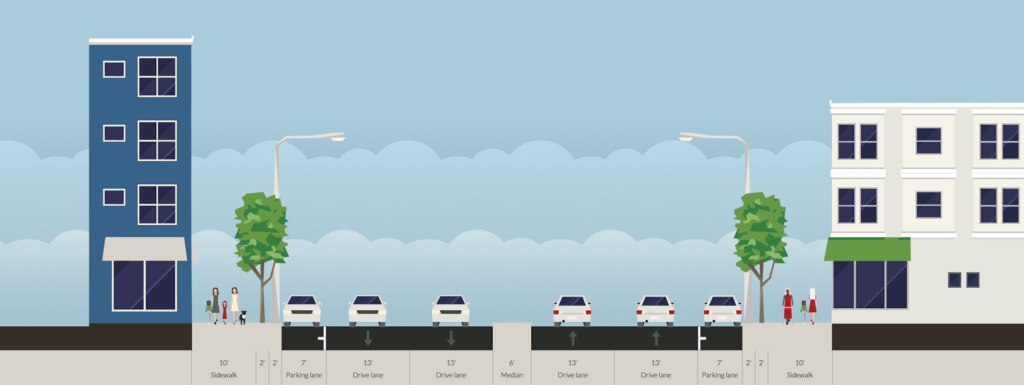

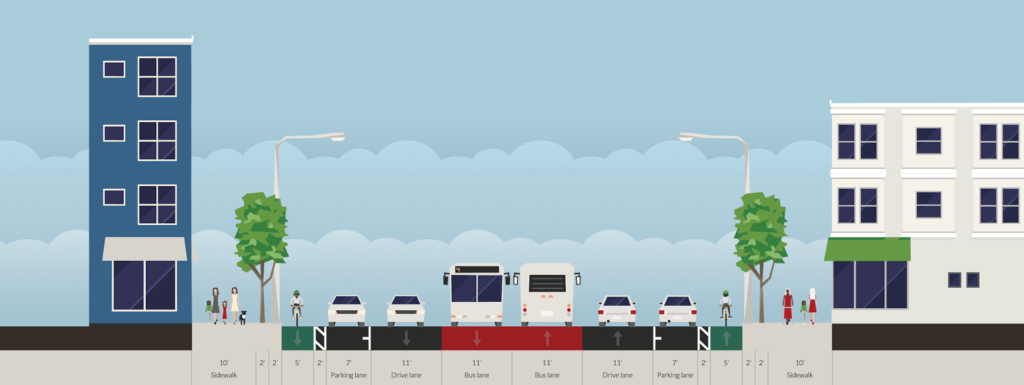

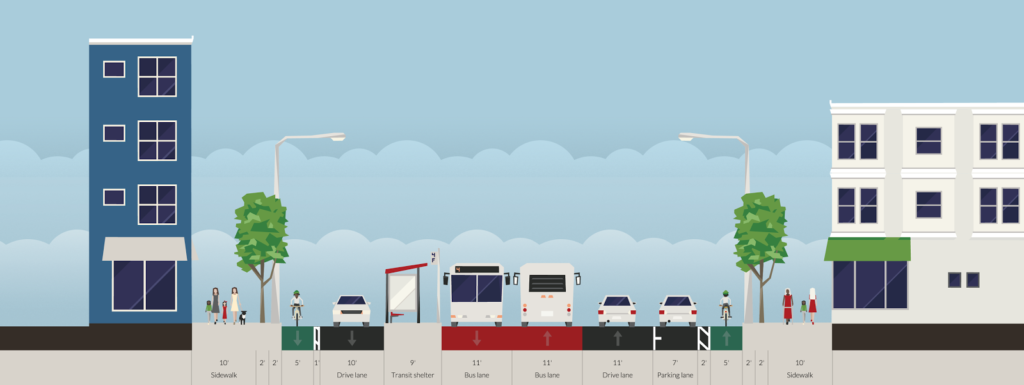

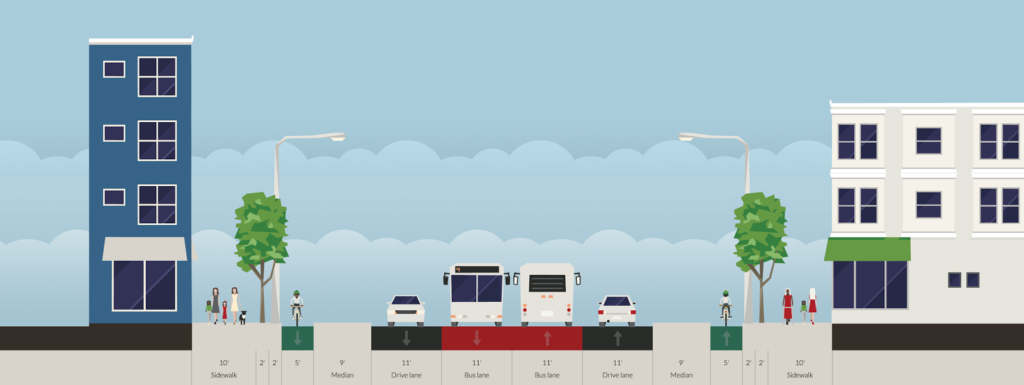

So I did more. I expanded the scope of the project to the entirety of the corridor, created GIS maps of the corridor with current and future street layouts, analyzed traffic counts and population, and created cross-sections in Streetmix between Central Square and the river. I then put these in to a Word Doc, with text and images separately, turned it in, and thought “I should rewrite this for my blog.”

That was more than a year ago.

It turns out that taking a 10,000-word document and getting it in to a web-ready, blog-ready format is a bit harder than meets the eye. But after watching bus upon bus get stuck on Green Street, and the bike lanes in Central Square constantly choked with livery and delivery vehicles, it’s time to get it on the web: a vision of a people-first Mass Ave in Cambridge. This post may depart a bit from the usual (poor excuse for) prose on this site with a bit less sarcasm than usual, but hopefully will be as informative as posts have been in the past.

Oh, and it’s long. Real long. Happy (?) reading.

Massachusetts Avenue has not always been Cambridge’s thoroughfare; in fact, it has not always been called Massachusetts Avenue. Until the Harvard Bridge provided the newest connection between Boston and Cambridge in 1891 (the only newer bridge between the cities is the Eliot Bridge far upstream) traffic between the two cities passed mainly across the West Boston or Cambridge (now Longfellow) Bridge downstream or the Cottage Farm (now Boston University) Bridge upstream. Mass Ave wasn’t even called such; Main Street stretched from the Longfellow to Harvard Square, beyond that was North Avenue.

In the past 125 years, Massachusetts Avenue has become the iconic street of Cambridge and, it could be argued, one of the most recognizable streets in the world, if not for the street itself but what lies along it. In a barely four mile stretch are Harvard and MIT, two of the world’s leading universities, three world-renowned music institutions (Symphony Hall, the New England Conservatory and Berklee College of Music), and Boston Medical Center. In Cambridge the street hosts the national or global headquarters of several major pharmaceutical corporations, and Boston University and Northeastern University lie just off the corridor as well. The Harvard Bridge has even spawned its own unit of measurement; the bridge spans 364.4 Smoots ±1 ear from Boston to Cambridge, something which can’t be said of 5th Avenue, Michigan Avenue, Sunset Boulevard or the Champs Elysees.

History: Mass Ave and Pattern Breaks

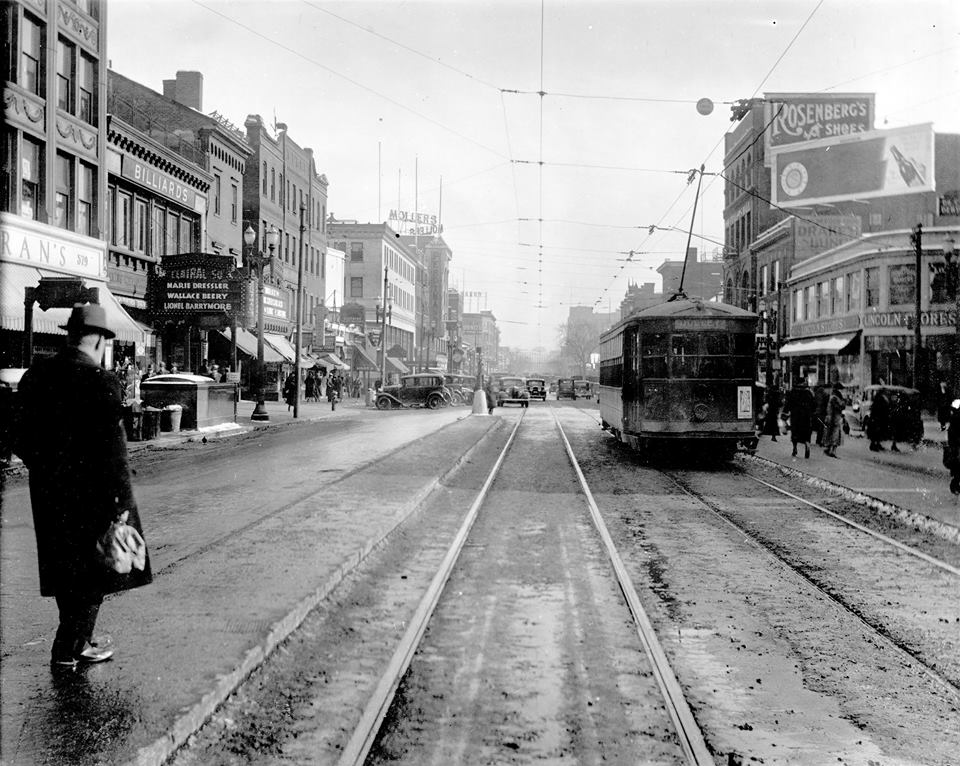

During this century and a quarter, Mass Ave has had three distinct “pattern breaks” when the use of the corridor has shifted. When the Harvard Bridge was built in 1891, the first electric streetcars had only rolled down the streets of Boston three years prior and it would be another decade until the first automobiles appeared. For the first 20 years of its life, Mass Ave was dominated by foot traffic and streetcars. (In fact, the first streetcar to use the Tremont Street Subway originated in Allston and rolled through Central Square early on the morning of September 1, 1897.)

The first pattern break occurred in the early 1910s, when the street was torn up for the construction of the Cambridge-Dorchester subway (now the Red Line). This dramatically changed the travel patterns through Central Square: no longer did streetcars run through the square; most now terminated in Central for a transfer downtown. Central Square became a major subway-surface transfer point between surface cars and subway trains. (The Boston Elevated Railway generally built complex subway-surface transfer stations like the Streetcar tunnel at Harvard or facilities in Sullivan and Dudley Squares. Central was the only major transfer point built with no separate infrastructure for streetcars, likely because the square had already developed and there was no room to do so. Even Kendall, which served only a couple of streetcar routes, had a streetcar loop-turned-busway until it was rebuilt in the 1980s.)

The next pattern break occurred more slowly in the 1950s and 1960s. The last streetcars rolled through Central Square in the early 1950s and the center-of-street-boarding streetcars and safety zone platforms were replaced with side-of-street bus stops as Central slowly went from being a transit node to a vehicular intersection. While the northern portion of Mass Ave was rebuilt with a median (and without streetcar stops) in the 1950s, Mass Ave wasn’t appreciably widened in Central Square, although it likely would have changed dramatically had the Inner Belt highway been built as planned, this delay and eventual cancellation may have saved the street from 1960s-era urban renewal. Still, the removal of the streetcar facilities led to an auto-dominated square, with wide expanses of pavement at the Prospect-Mass and Mass-Main intersections and a reduction in the mass of many of the buildings (so the owners could save property taxes) resulting in many of the single story buildings and parking lots today.

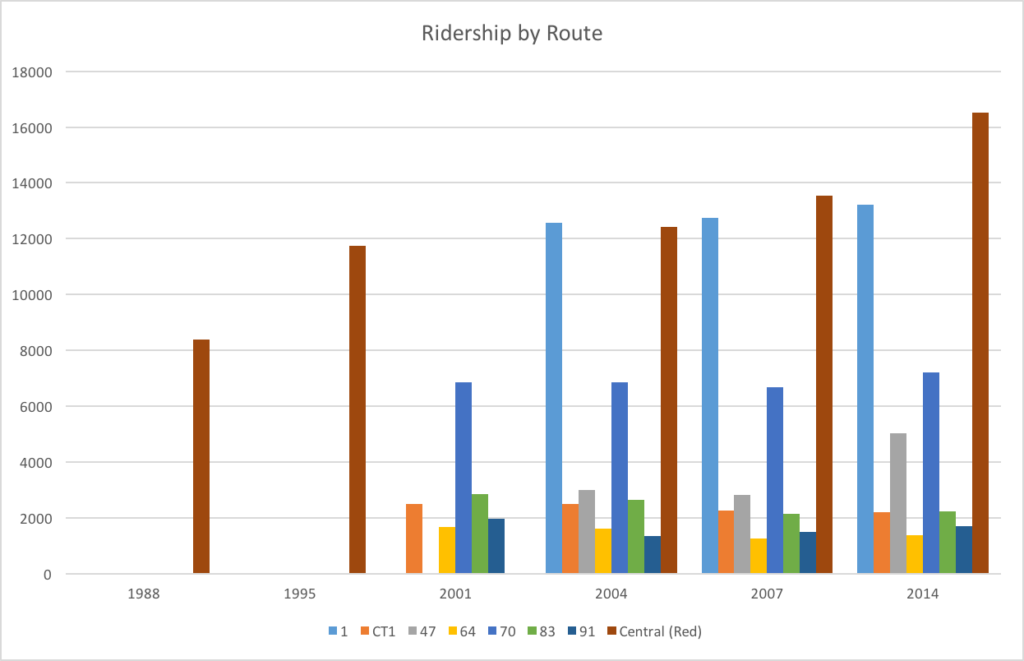

In the past decade, vehicle traffic volumes on Mass Ave have decreased while at the same time transit use and cycling has increased: bike counts have more than doubled in the past decade and Red Line ridership in Central has doubled since 1988. Unfortunately, the allocation of road space has not kept up with these changes. It’s time to design a new pattern break for Mass Ave’s infrastructure to catch up with the behavioral pattern break of its users.

The Context of Massachusetts Avenue

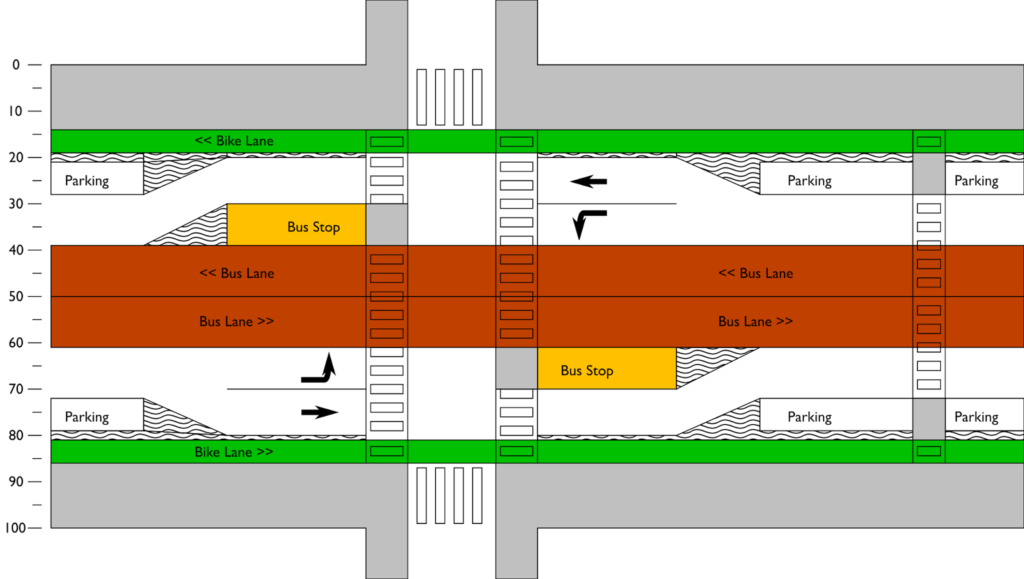

Massachusetts Avenue is home to some of the richest human capital in the world, yet it is congested at best and dangerous at worst. The street hosts several MBTA bus routes and the MASCO shuttle, but the passengers on these buses are regularly subjected to congestion delays despite, at rush hour especially, outnumbering people in cars. Several cyclists have died on the street in recent years, and the bike lanes installed in the past two decades are inadequate and outdated; they provide little protection from car doors and passing or turning vehicles and are frequently used by drivers as convenient double parking spaces. Parts of the street, when not congested, are straight and wide, encouraging motorists to travel at high rates of speed, which is not conducive to a safe environment for other users.

Cambridge has made improvements to the avenue between Central Square and Memorial Drive in recent years. It’s hard to believe that a decade ago Lafayette Square was a sea of pavement (now a park) and bicycle lanes were not yet installed. This roadway was narrowed in many places from four lanes to three. While it was an improvement, it was also a missed opportunity: the street still prioritizes cars over other users. No provisions were made for transit users, and the roadway is still focused mostly on providing throughput and parking for automobiles, with transit users and cyclists a decided afterthought.

Cambridge is growing—the population is up 15% from 1990 to levels not seen since the 1950s, and Kendall Square is continuing its transformation from a collection of parking lots in to one of the major high tech centers of the world—but traffic is not. On Mass Ave at Sidney Street, it has declined 30%, from 19,400 in 1999 to 13,600 in 2013. While demand may have required four lanes in the 1950s before the regional highway system was built, it does not today: the worst congestion in Cambridge is due mainly to downstream effects (throughput issues in Boston often back Mass Ave across the Harvard Bridge). Over this same time period, transit ridership is up, and the proportion of Cambridge residents and workers commuting by car is down: the majority now walk, bike and take transit to work.

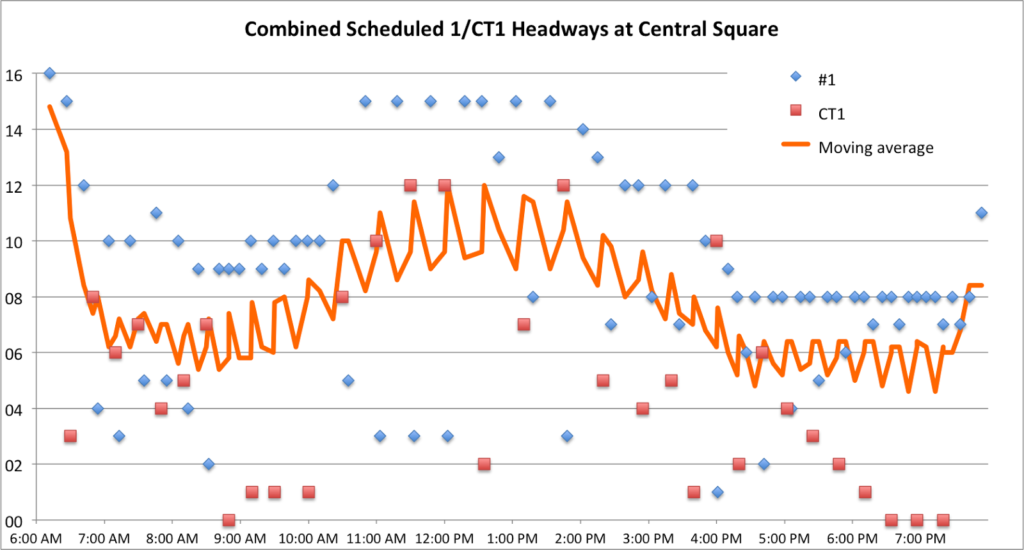

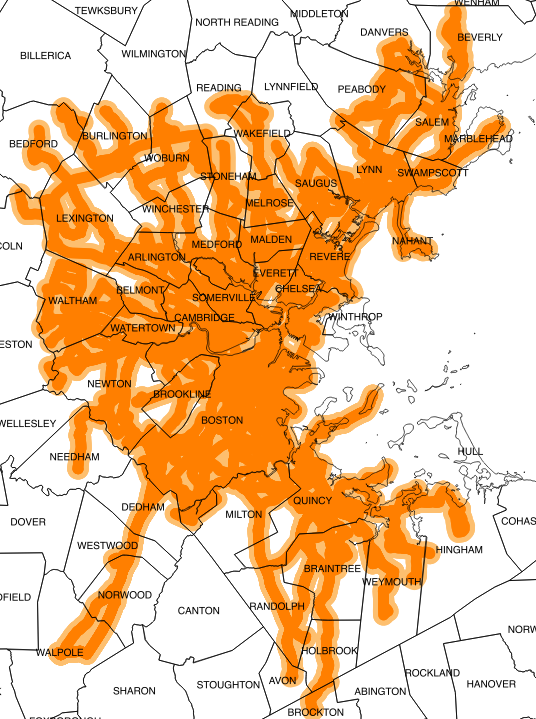

|

| Ridership on most transit serving Central Square is growing. Data from MBTA Blue Books. |

How to Analyze Mass Ave

So the question must be asked: if the majority of the users of Massachusetts Avenue (and Cambridge in general) do not travel in cars, why is most of the roadway given over to traffic and parking? The right-of-way should be reapportioned based on the current use of the roadway and future trends. The City has laudable mode shift goals and has made progress towards attaining them. However, it is important that the design of the city’s streets is commensurate with these goals: empty roadways will lead to induced demand as more people rely on single occupancy vehicles, while slow transit and dangerous cycling facilities will provide a disincentive towards non-auto modes. This creates a vicious cycle as more vehicles cause more danger for pedestrians and cyclists and more congestion for transit users. (Providing faster and more reliable transit provides a virtuous cycle: more passengers require more frequent service, which reduces wait times and increases demand further.) Vehicle throughput on Mass Ave is important, but it has been the singular top priority for far too long. This must change.

The long term goals for Mass Ave need to be about prioritizing the safety and throughput of all users, in four major groups: pedestrians, cyclists, transit users and motorists. It is hard to argue that safety of all users should come before throughput in any design (within reason) and the safety of users can be relatively easily ordered as follows by vulnerability:

- Pedestrians

- Cyclists

- Transit users

- Motorists

Note that this is not a linear scale: safety for pedestrians and bicyclists is much more important than for other users, since they are far more vulnerable users. Safety between different groups is very much correlated: a road which is safe for pedestrians and cyclists is almost always safer for motorists as well.

Once you solve for safety, the next step is to solve for throughput. Ordering users here is a bit more complex. It may be best to order modes by the current number of users on the roadway, as well as the potential. For instance, if transit was faster and more frequent, the roadway could accommodate many more transit users, and there are already more transit users on Mass Ave than people in cars at rush hour. (The 1 bus, which is an important crosstown route between the Red Line and Orange and Green Lines, is often slower than making a connection downtown due to congestion on Mass Ave. If it were reconfigured as a bus rapid transit line through Cambridge and Boston, it could reduce the strain on the overburdened Red Line.) The MASCO shuttle runs at or above capacity on Mass Ave as well, and providing it bus lanes would make its trip significantly faster than it does today. The City and MBTA could work with MASCO to provide easier access to the service for the general public (it is currently open to the public, but requires a separate fare paid with a Harvard ID, a high barrier to entry for casual users) in exchange for the use of transit lanes.

Likewise, a safer road for cyclists may attract many more cyclists (as Cambridge has provided safer cycling infrastructure in recent years, bicycle counts have more than doubled). Cambridge has a bicycle network plan to add separated bicycle facilities to most major roadways, including all of Mass Ave. This post will attempt to do just that.

On the other hand, the number of motorists on the roadway is constrained both by the roadway width and layout as well as upstream and downstream bottlenecks: it would be difficult to add many users to Mass Ave without widening other roads far afield from the corridor. Pedestrians are numerous along the avenue, but are far more able to withstand bottlenecks within reason, although by no means should be plan to narrow sidewalks in the middle of Central Square and other high-pedestrian areas.

With this in mind, throughput goals should be ordered as follows:

- Transit users

- Bicyclists

- Pedestrians

- Motorists

This is not to say that we should kick motorists to the curb (so to speak). But when looking at various segments of the roadway, it is a good guideline to see if our priorities are askew. For instance, are we arguing against separated bicycle facilities (or protected bike lanes or “PBLs”) to maintain parking on both sides of the street? Are we forcing hundreds of bus passengers to narrow, crowded stops to facilitate a left turn used by only a few motorists an hour? Are we creating space for vehicle queues where we could instead have a transit lane to allow bus passengers to pass slow-moving traffic?

This post will use this approach to consider the stretch of Mass Ave between Memorial Drive and Central Square. West of Central Square, Mass Ave is quite narrow: the street is only 44 feet wide. This section has the least traffic and is rarely congested, and while a complete streets treatment may be warranted, it would not be possible to provide transit lanes and PBLs even with all parking eliminated. (North of Harvard Square is beyond the scope of this post, but that section of street was redesigned in the 1950s to eliminate safety island streetcar stops and build a wide highway-like road, a design which begs to be rethought. In fact, the city actively campaigned against the safety islands for the streetcar, which may have helped lead to its demise. The cars operating from the North Cambridge carhouse to Arlington Heights, Waverley and Watertown were the last cars operated by the MTA which didn’t feed the Central Subway in Boston. Whether streetcar service would have survived with the city’s support is an open question. This page has some opinions on that.) It will break the Avenue in to two parts: one stretching from Memorial Drive to Sidney Street, and a second from there through Central Square past City Hall. It will then discuss strategies to implement best implement this plan in the short and longer term. For the most part, it will attempt to rebuild the roadway within the current curbs and right-of-way, although in several areas will propose shifting curbs and, in a few, widening the right of way in to currently-unused space.

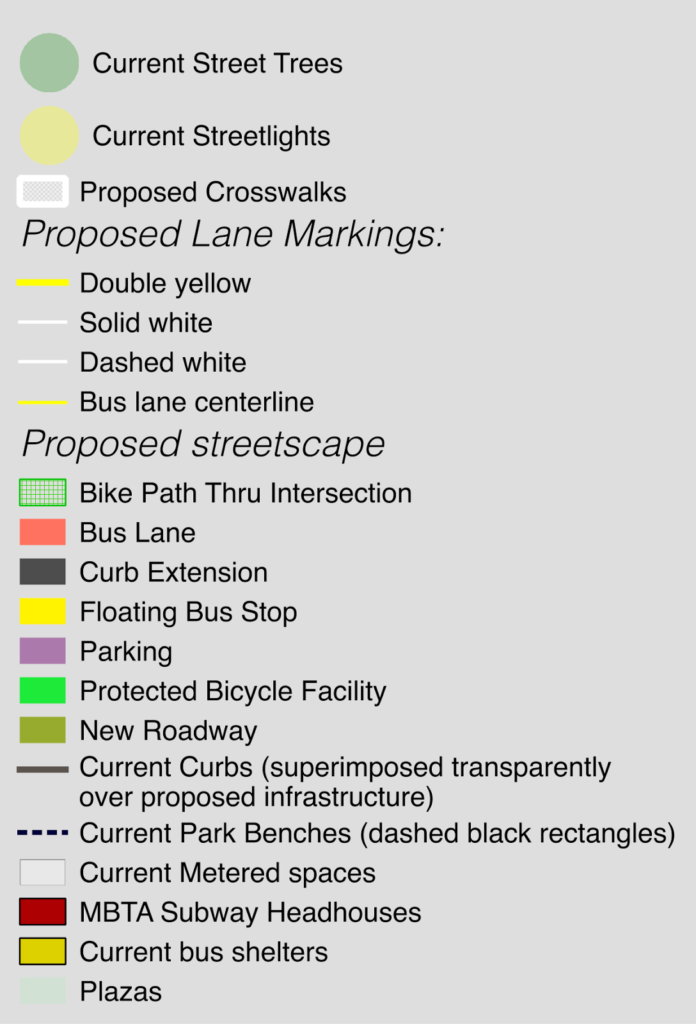

|

| Legend for maps. Data generally from City of Cambridge. |

A few notes on syntax:

- Mass Ave will be referred to as westbound towards Harvard Square and eastbound towards Boston. Cross streets will be referred to as northbound and southbound.

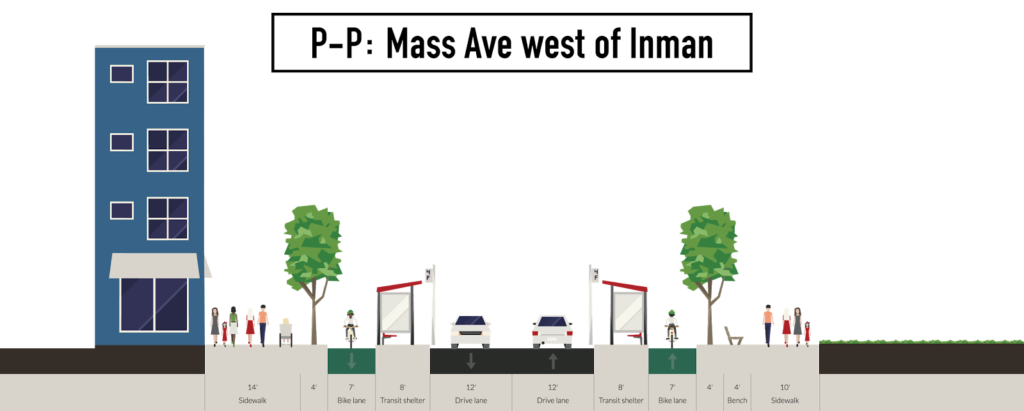

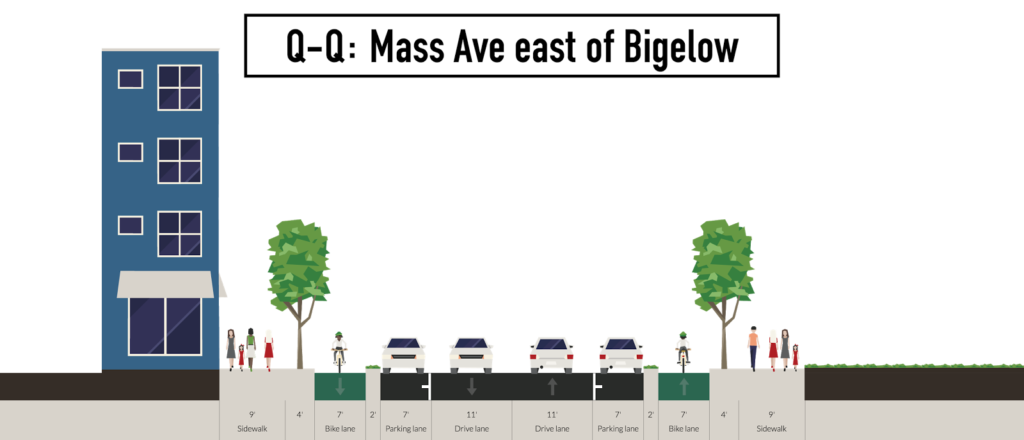

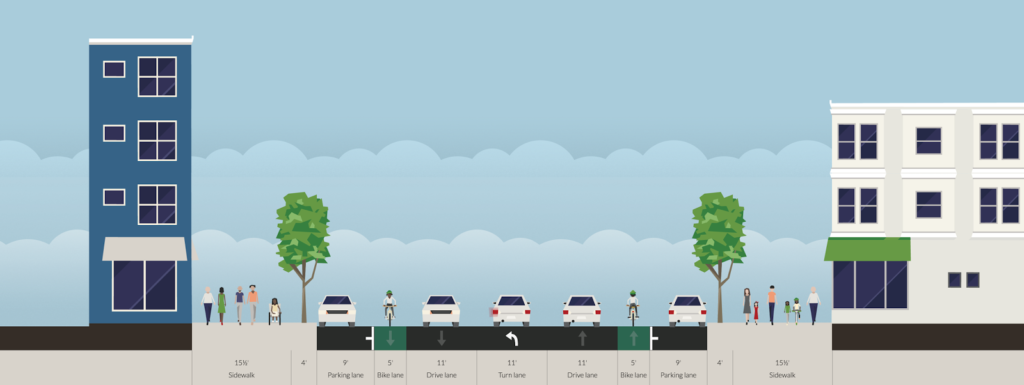

- All cross sections will be looking west, with the Cambridgeport side on the left and the Area 4 side on the right.

- PBL = Protected Bike Lane, also known as a separated bicycle facility or a cycletrack. PBLs can either be sidewalk level or at street level, and can be set off by curbing, bollards or parked cars and a painted median. Sidewalk level PBLs are generally preferred.

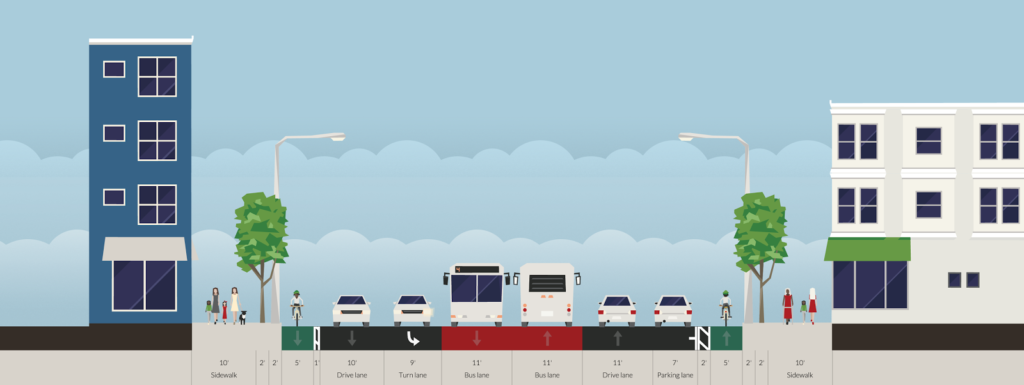

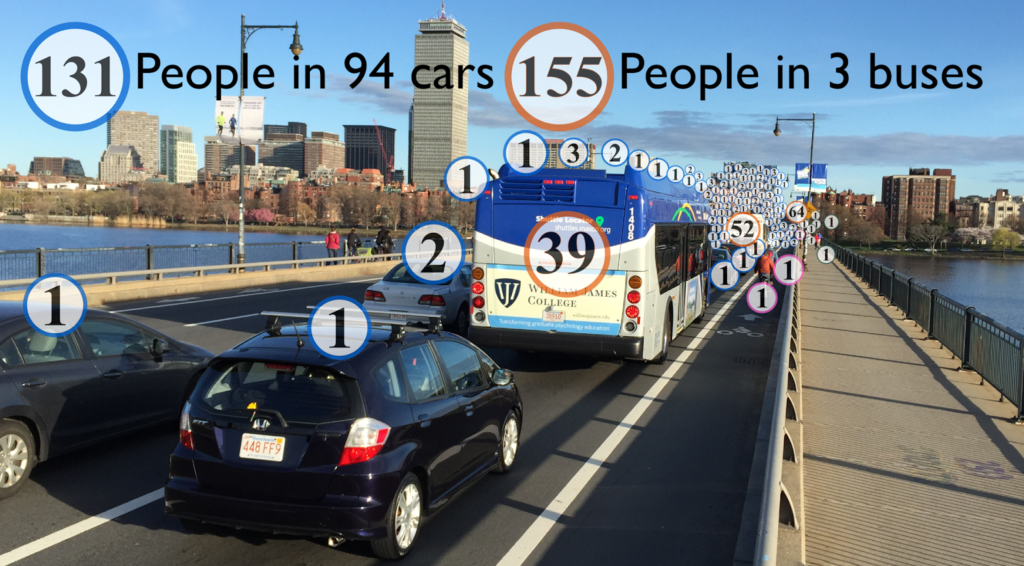

- Bus stops are generally shown as “floating bus stops” which allow some traffic (bikes, or bikes and cars) to pass to the right. Bus lanes are generally best located in the middle of the street, especially since curbside lanes preclude any other curbside use.

- All street cross-sections are from the Streetmix.net website.

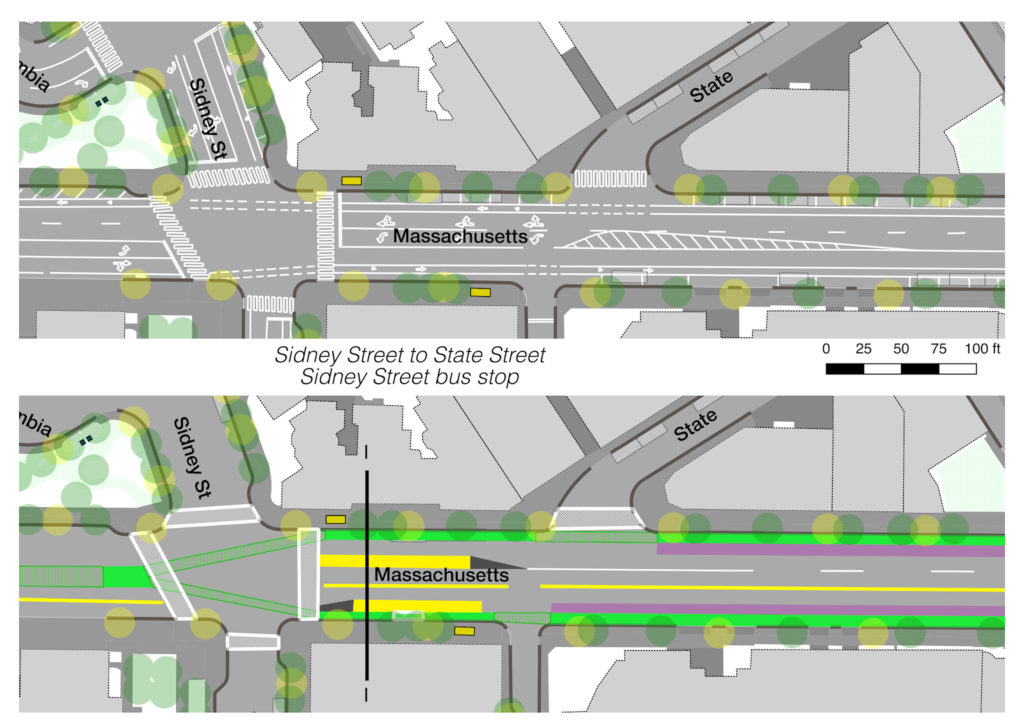

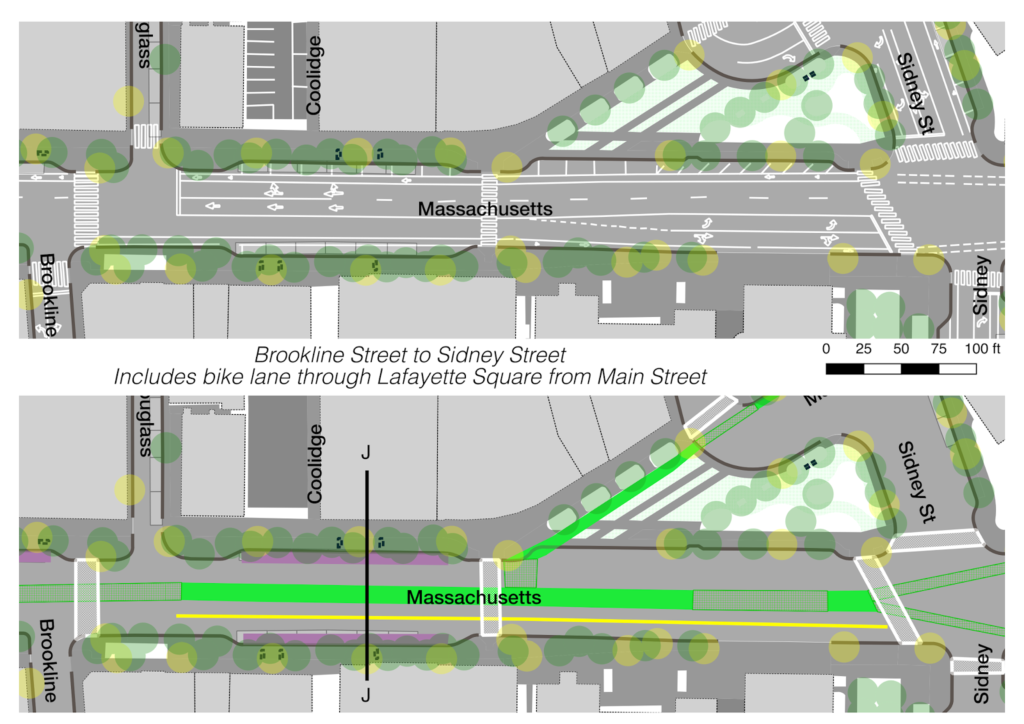

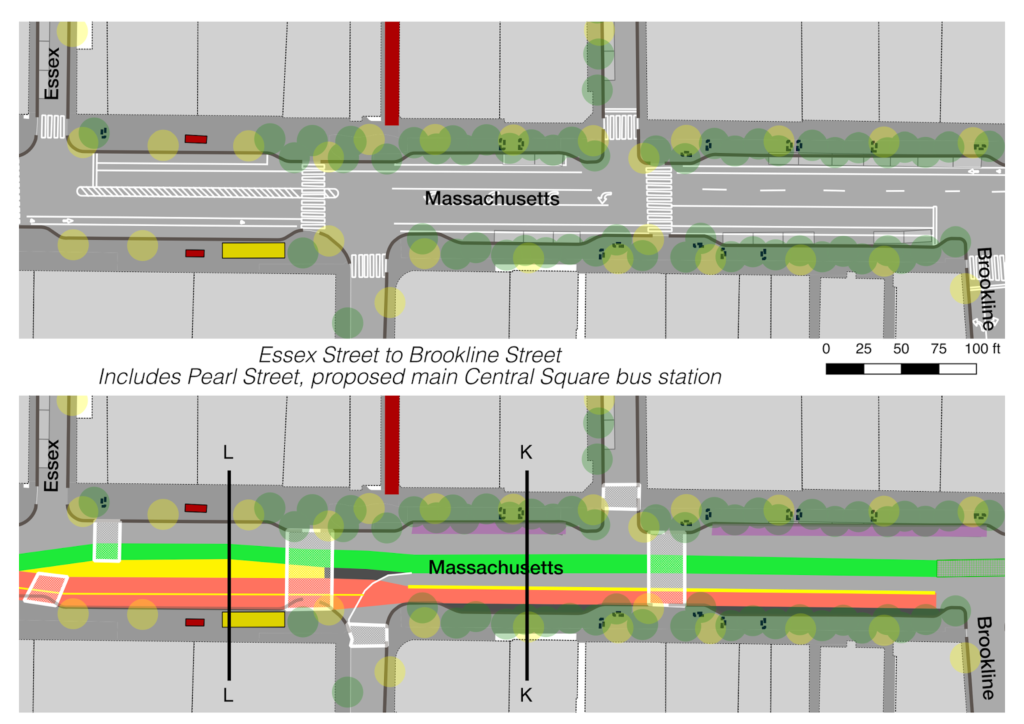

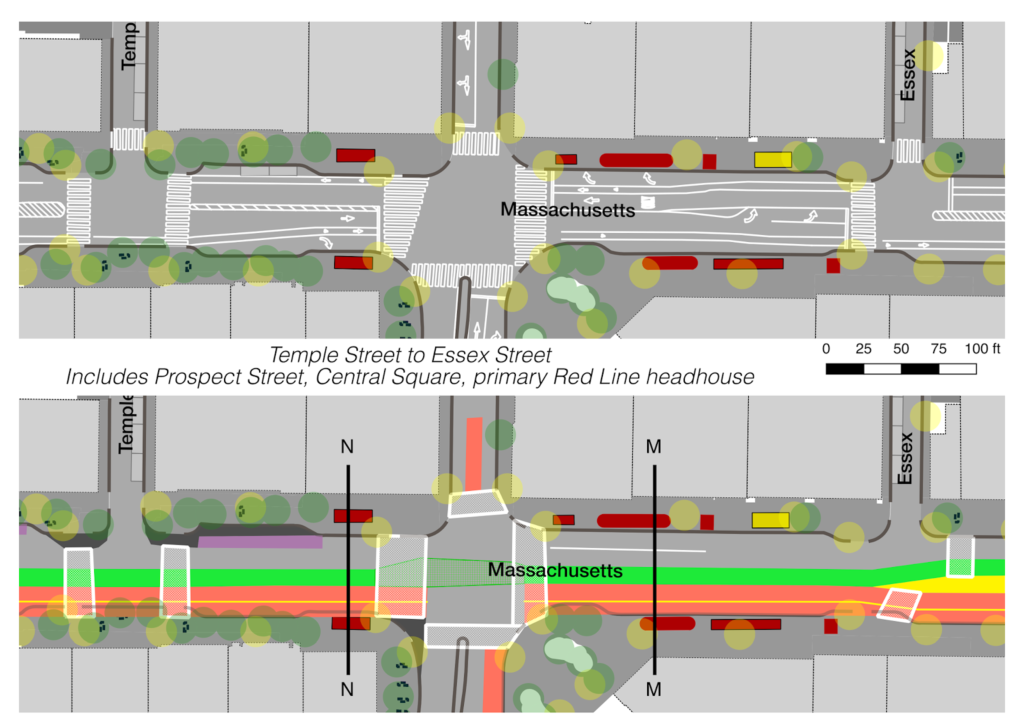

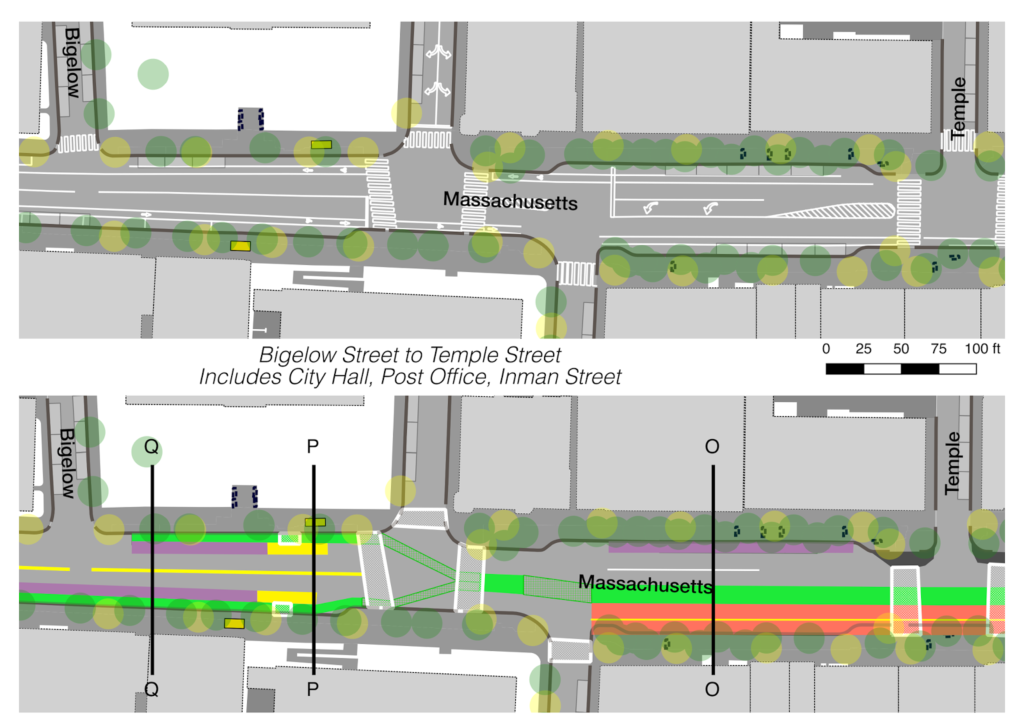

- Each map shows the current condition of the street on top, an the proposed layout below.

MIT: Memorial Drive to Sidney Street

Memorial Drive and the Harvard Bridge

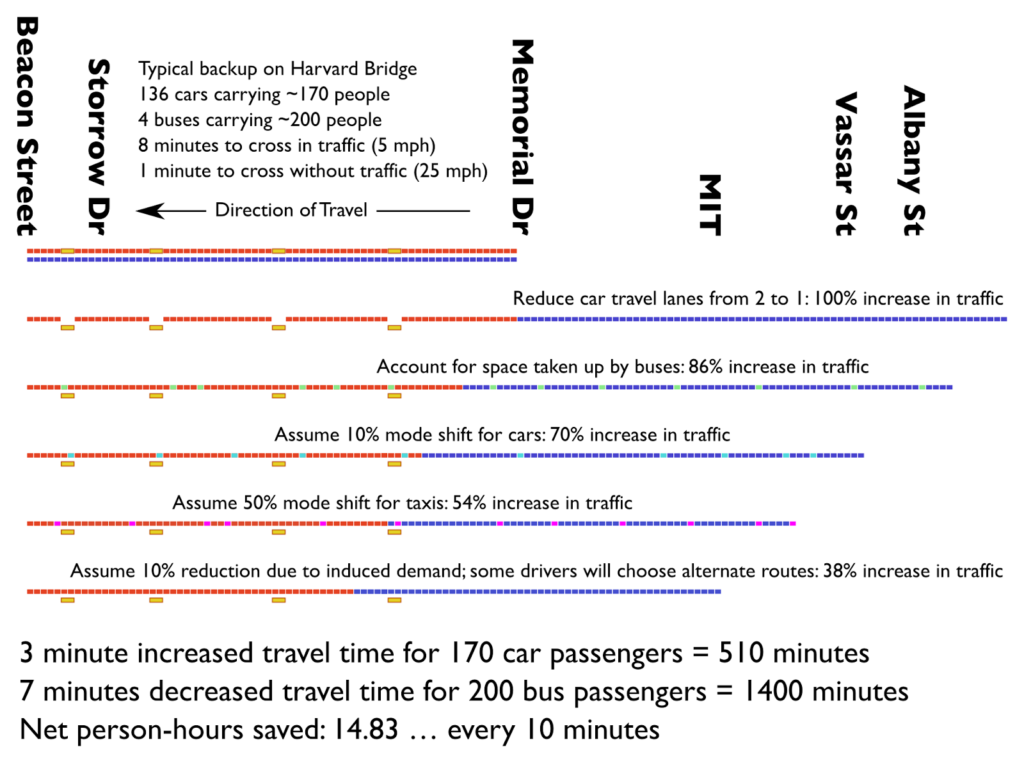

Before focusing on the Cambridge portion of Mass Ave, a note should be made about the Harvard Bridge. The bridge carries tens of thousands of bus passengers, motorists and cyclists daily between Boston and Cambridge, but is too often choked with traffic, especially eastbound in the evening, when queues often back up across the bridge and in to Cambridge. Bicycle lanes were only recently extended all the way across the bridge (previously, merge zones at the end were quite dangerous for cyclists) but are still suboptimal for bicycle safety, with storm drains on the right and fast-moving traffic on the left. When not queued, vehicles drive quite fast—especially motorists exiting Storrow Drive who are used to highway speeds (it is possible to drive directly from I-93 to Mass Ave without encountering a traffic light or pedestrian until exiting Storrow)—on the straight, wide roadway.

For traffic traveling westbound, there are neither concurrent walk signals with a green phase nor a “no turn on red” sign, so pedestrians either have to wait for a walk signal which is still often crossed by traffic or walk against the signal, despite through traffic having a green light. (This is an extremely busy pedestrian area.) Without any commercial traffic, this right turn could easily be made more severe with more restrictions (or even rebuilt as a raised crossing to further slow traffic) and priority could be given to pedestrians instead of cars. As for transit, it receives no priority, and there are frequently three or four buses stuck in a queue on the bridge. When this is the case, however, these buses carry more passengers than every other car on the bridge.

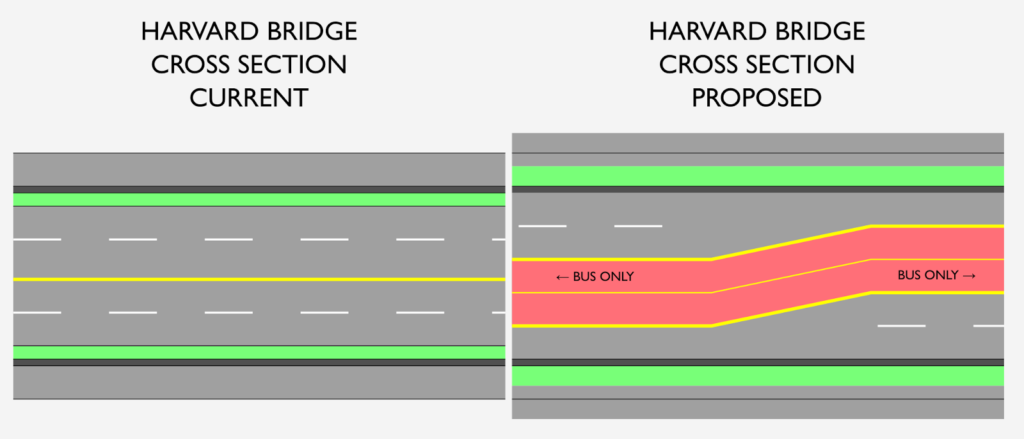

The bridge is maintained by MassDOT, with the cities maintaining the approaches at either end. The bridge environment could certainly be improved with better separation for bike lanes, narrower travel lanes to curb speeds, and bus lanes to prioritize transit users crossing the bridge. A more outside-the-box idea would be to cantilever an additional six feet of sidewalk on either side of the span and move the bike lanes to the right side (in both senses) of the crash barrier, allowing five lanes of traffic: through bus lanes and queue space at either end of the bridge. Extending bus lanes in to Boston would be necessary as well. This would require cooperation of both cities and multiple state agencies: certainly a high bar to clear but by no means an impossibility. This post will assume that this is indeed possible.

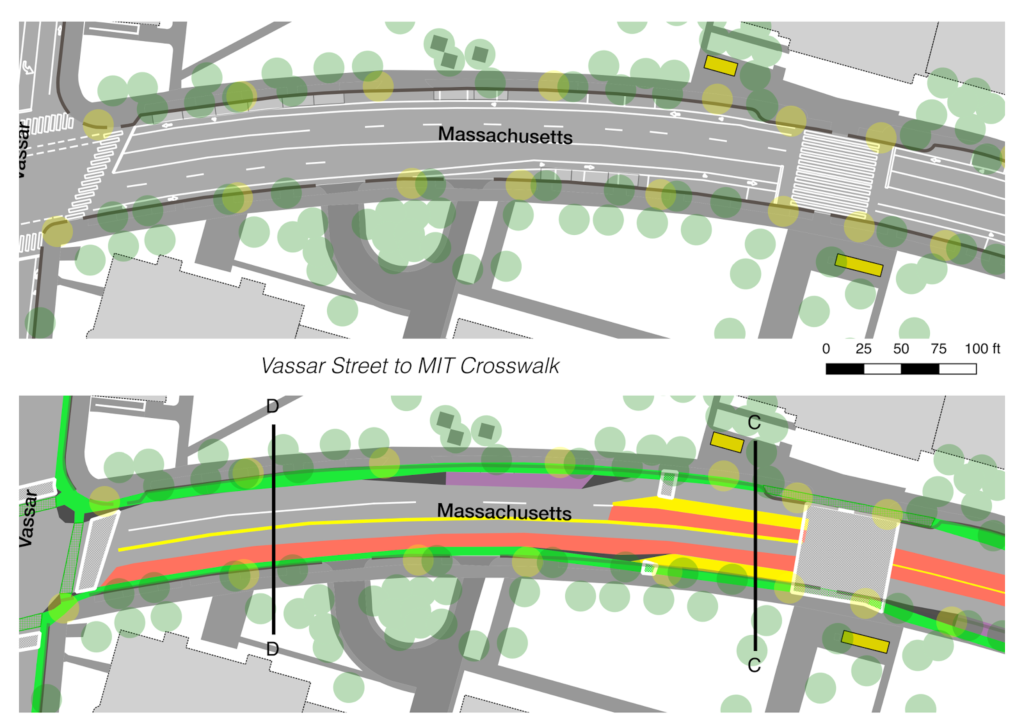

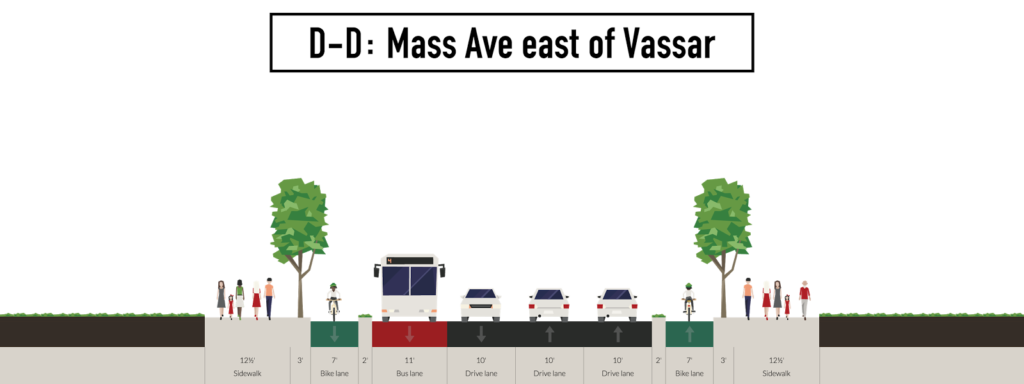

Memorial Drive to Vassar Street

Crossing the bridge, Mass Ave bisects the campus of MIT. The roadway varies in width but the right-of-way is generally 90 feet, while there are two westbound lanes from Memorial Drive past Albany Street, the eastbound roadway narrows from two lanes to one lane in front of MIT. There are small street trees planted along the curb, but they are overshadowed by the stately oaks on MIT’s campus.

The main actor against a more balanced street here is parking. While there is the need for some short-term parking (or perhaps just pick-up/drop-off space) in this corridor, two-hour parking is by no means the best use of this space. If the average space is used by 15 vehicles per day, the 28 spaces between Memorial Drive and Vassar provide parking for 420 users per day, which is barely 1% of the total throughput of the street, yet it accounts for 16% of the right-of-way. Parking at MIT, while somewhat constrained, is still ample: the institute has parking available on Amherst Street (which it controls), along Vassar Street and in many lots and garages.

The usual fallacy that removing street parking will harm small business doesn’t even ring true unless we consider MIT and it’s $14 billion endowment as a small business. The city would have to work with MIT to reallocate parking, but this should not be a particularly heavy lift, especially since charging for parking on Memorial Drive could allow better turnover and availability in the area. One other displaced user would be the tour buses which park along Mass Ave in front of MIT. These users should not be prioritized but still accommodated, and MIT and the city should work to find off-street parking for these buses (perhaps in the lot adjacent to Mass Ave and Vassar Streets or on Amherst Street) where they will be out of harm’s way.

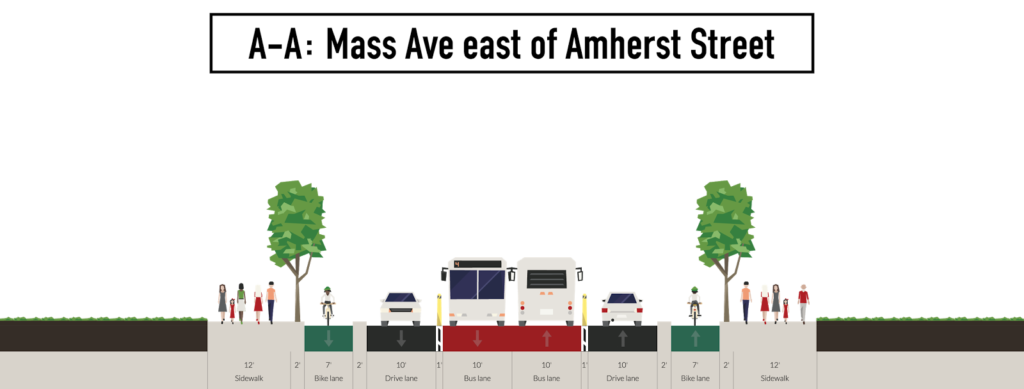

For westbound traffic coming off of the bridge, the left turn to Memorial Drive could be eliminated, and bus lanes extended across the bridge. Traffic wishing to access Memorial Drive westbound can take a right on to Memorial Drive and use the U-turn to the east to go westbound, a move often called the “Michigan Left” because of the preponderance of its use in the Great Lakes State. The right turn from the bridge to Memorial Drive could be sharpened and perhaps raised to slow vehicles in this high-pedestrian area. Rather than two lanes through campus, through traffic would be funneled in to a single lane, with the left lane reserved solely for buses. The bike lane would be moved to a sidewalk-level lane, which would move cyclists from the “door zone” of parked cars to a safer facility (as is planned for the entire corridor to Central Square). Westbound cyclists would have a specific bike light at the Amherst Street T intersection, which could be set to flashing red during the Amherst portion of the cycle to allow bikes to proceed after yielding to pedestrians since there are no vehicular conflicts.

The large MIT crosswalk could be rebuilt as a raised cross similar to the crosswalk in Kendall Square to slow traffic, although it likely needs to retain a signal due to the higher volumes of vehicle and pedestrian traffic. The bicycle facilities would create a slightly wider roadway and may require a slightly longer light cycle for pedestrians than exists today. Floating bus stops—not a new concept, but rather a direct descendant of streetcar safety islands which were first used in Cambridge in 1922—would be placed to the west of the crosswalk and accessed during the pedestrian phase. Past the bus stop, the left lane’s exclusive use for buses would end and allow left turns to Vassar Street. Approximately four parking/loading spots would be provided on the north side of the roadway.

The Vassar Street intersection will be changed dramatically and discussed in detail below.

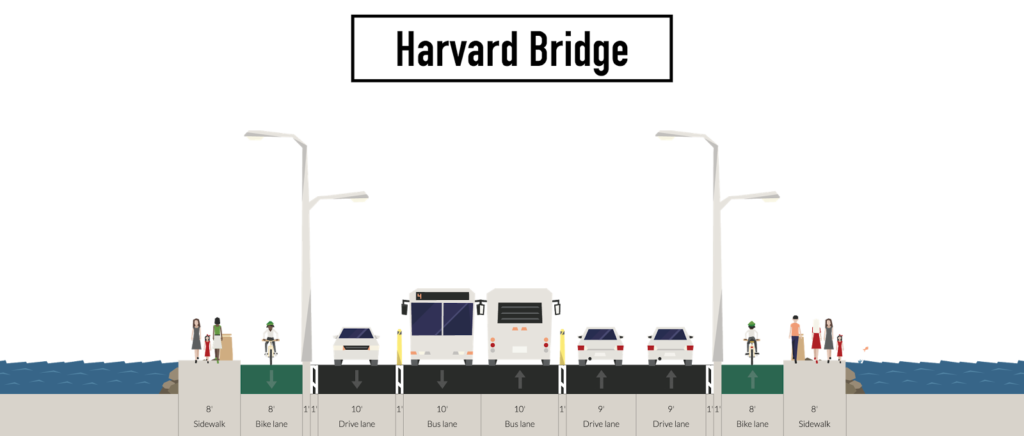

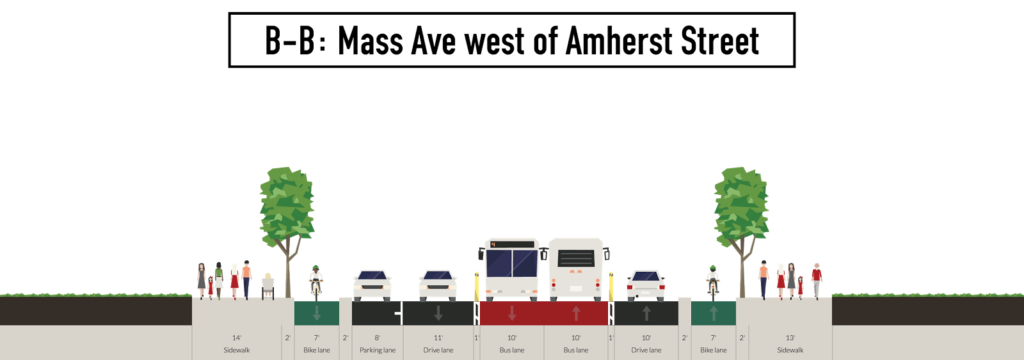

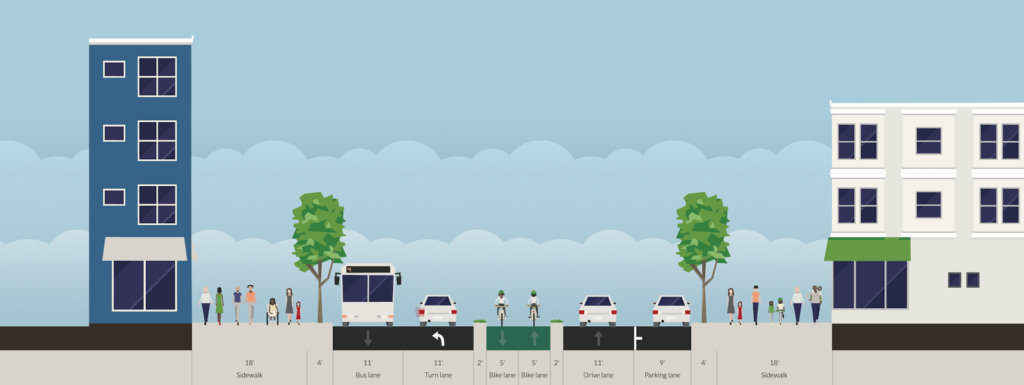

Coming east from Vassar Street, a single through vehicle lane will be provided to the left with buses and turns into and out of the MIT bus loop on the right. The separated bicycle facility will run to the right of the bus lane, moving in to the current sidewalk right-of-way before the bus stop. (the right-of-way may need to be widened slightly here with MIT’s cooperation). Coming east crosswalk will serve two purposes, both to allow the passage of pedestrians and to allow the swapping of the bus and general purpose travel lanes. When the bus stop is occupied by a bus, the next cycle will have a transit only phase for eastbound traffic, allowing the bus to proceed diagonally to the left-side bus lane before a green light appears for general purpose traffic (a right-side bus lane could be retained across the bridge, but might not be preferable). Making this switch allows vehicles to move to the right side of the roadway, where several parking or loading spaces are provided, and for the transit vehicles to move to the center lanes for a speedy trip across the bridge. These spaces require some extra road width, but can be attained by moving the cycle track on to the sidewalk, which is quite wide between the crosswalk and Amherst Street; some cooperation between MIT and the City would likely be necessary. (See cross-section B-B.) Between there and the river, three exclusive lanes would be provided for cyclists, motorists and transit. (See cross-section A-A.) Since the bridge is controlled by a separate entity from the rest of the street, side transit lanes could be retained until bus lanes were installed on the bridge of the agencies’ schedules didn’t match.

Mass Ave and Vassar Street

|

| The acute angle from Mass Ave to Vassar Street requires trucks to roll up on to the sidewalk—which is often filled with pedestrians—to make a right turn. |

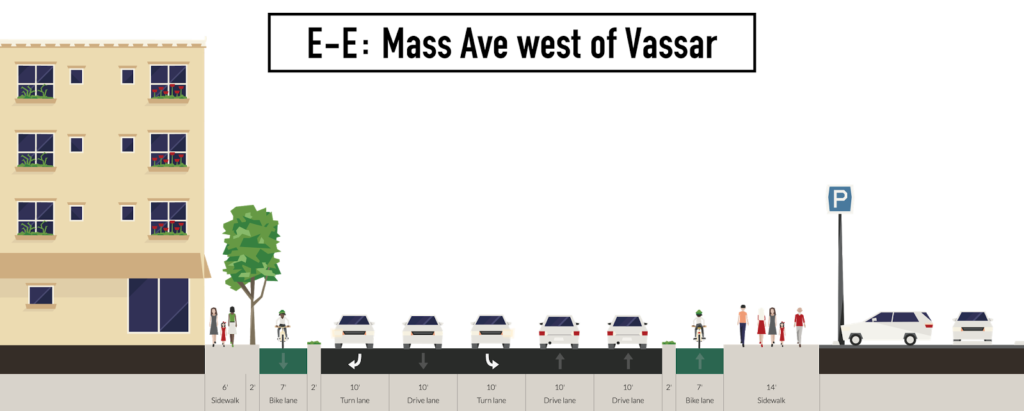

Vassar Street is one of the most complex and quite possibly the most dangerous intersection in the Mass Ave corridor. It has been the location of the death of a cyclist in 2011, and many more close calls. The roads do not cross at a right angle, and there is significant turning traffic. The crosswalks are long and askew, and turning vehicles often block the bike lane only to wait for pedestrians to cross before they are able to make their turn (if they don’t “take initiative” and attempt to weave through the crowds). A short term fix would be to make the right lane of Mass Ave westbound right-turn only, and have a red turn light for most of the signal’s cycle, but a green arrow during the exclusive left turn phase on Vassar Street. This would be similar to the setup where at the corner of Granite, Waverly and Brookline streets north of the BU Bridge, and the new phased right turn light on Comm Ave immediately south of the bridge. This would allow safe passage by cyclists and pedestrians during the Mass Ave phase, and an exclusive turn for cars when the street is already blocked. This would require that the eastbound side of Mass Ave become a single through lane (with the left lane for left turns only; this is already the de facto use of that lane) and might require three westbound lanes: a left turn lane, the current through lane, and a right lane for queuing cars waiting for the light. This, however, would preclude the start of the bus lane on the eastbound side of the street, so the tradeoffs would have to be examined.

In the longer run, since Vassar Street is home to Cambridge’s first cycletrack and, if it intersects with a protected bicycle facility on Mass Ave will require a different treatment. (As an earlier iteration of a PBL—in fact, one of the first in the nation—the facility is somewhat substandard, and separation must be extended on Vassar through the Mass Ave intersection. If built today, it would likely look much more like the Western Avenue facility.) This intersection begs for a better a better design. Luckily, there is one: a protected intersection.

Protected intersections are used commonly in Europe (especially in the Netherlands) and the first have recently been installed in the United States. The City of Boston is planning one along Commonwealth Avenue in the area of Boston University. A protected intersection moves cyclists adjacent to crosswalks and creates sharper turns for drivers, decreasing speeds and allowing for better sightlines. In addition, it allows left-turning cyclists to cross the intersection and then take a left, rather than having to merge in and out of traffic. With intersecting PBLs, such a treatment is often required.

This intersection is generally large enough for a PBL, but some modifications to the intersection would need to take place. The east and west corners would have to be extended to provide better bicycle crossings and queueing space. This would require a sharper turn for traffic turning from Mass Ave east to Vassar south, although this is a relatively rare movement. The eastern corner would need to be rebuilt as well, since the current shallow curve does not serve the purposes of a protected intersection to calm traffic and allow better sight lines. This is a more frequently-used movement, and congestion may be exacerbated by this change.

This could be mitigated by eliminating the right turn there altogether and providing more queue space for right turns on to Albany further west, as this post proposes. This intersection is frequently choked by cars attempting to turn from both lanes, with left-turning cars stymied by eastbound traffic and right-turning cars waiting for a constant stream of cyclists and pedestrians. Removing this turn would allow better throughput towards Albany Street, mitigating backups towards Memorial Drive. For most motorists, the extra one or two minutes to access Kendall Square is negligible, and Vassar is a narrow, often congested street. As discussed later in this post, the Albany Street intersection could be reconfigured to better accommodate this traffic.

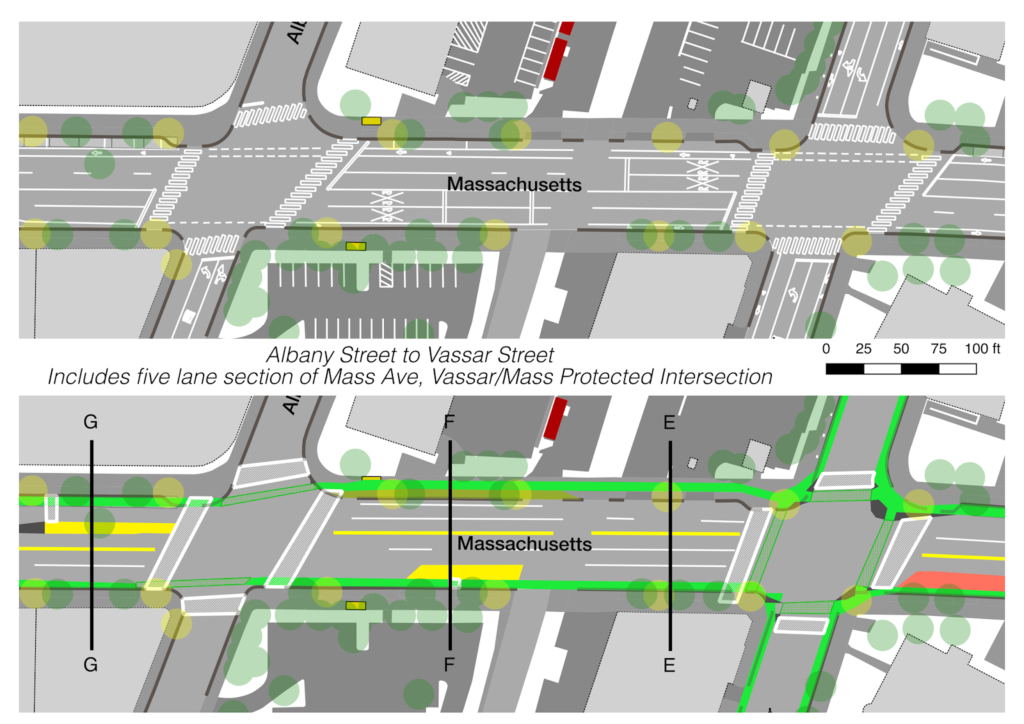

Vassar Street to Albany Street

The section between Vassar and Albany Streets is unlike any other in the corridor: it has a mid-block railroad crossing of the Grand Junction line. There is minimal queue space between the two streets, and the area is often congested, causing backups through the intersections at peak hour. Other than parking lots and MIT deliveries, there are no abutters requiring access to the street which is bounded by two parking lots, the blank brick wall of a warehouse and a small laboratory which faces on to Albany Street. Even if redeveloped, it will likely never be an opportunity for placemaking with the rail line and delivery corridor running through the center. While this post generally calls for the downsizing of the streetscape, in this case, it calls for additional traffic lanes. By providing a wide roadway in this section, queues would be minimized in adjacent segments and the potential lights at Vassar and Albany to impact each other would be minimized.

This additional space is not free, of course, but the right-of-way here can be widened: the 90-foot right-of-way could easily be widened by ten feet or more on the north side. This assumes that PBLs would be located to the right of the travel lanes. Most likely, this would require a new PBL on the south side of the current roadway to account for two mature trees abutting the road, and moving the northernmost PBL in to the area occupied by the sidewalk and the sidewalk in to unused space and a parking lot owned by MIT. Obviously, MIT’s cooperation here would be required.

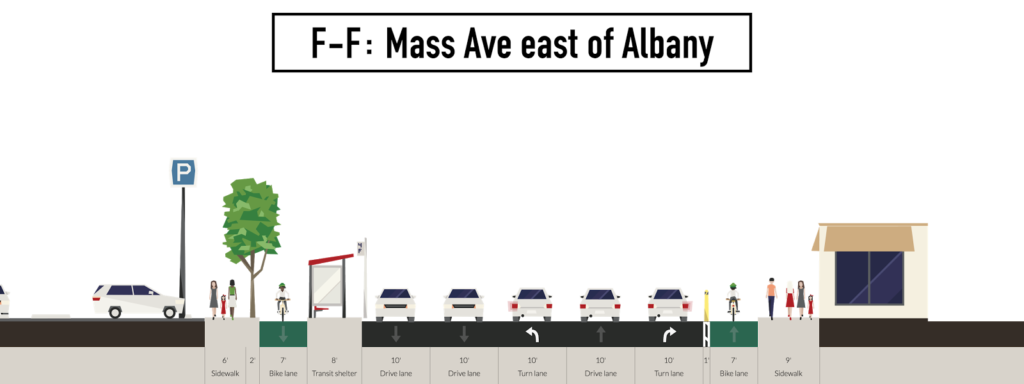

For westbound traffic, this would allow two lanes of traffic east of the Grand Junction widening to three beyond. These three lanes would allow an exclusive lane for each turning movement at Albany Street, the busiest single junction east of Central Square during the morning peak hour (and the busiest cross street by total vehicles). Going eastbound, Albany Street splits in to Albany and Portland with no stop sign or other traffic control device, so queuing space is not an issue, traffic entering Albany is unlikely to back up across Mass Ave (in fact, Mass Ave is often the bottleneck itself, and Albany backs up from Mass Ave south towards the BU bridge). The three lanes could be used exclusively for left, straight and right movements to clear traffic out of the short queue from Vassar Street, with the bus stop relocated west across Albany (far-side bus stops are generally preferred). With the right turn at Vassar disallowed, a number of steps could be taken to ease the right at Albany. First, the bike lane would be curved slightly and curb extended to allow for better sightlines between through cyclists and turning vehicles. Second, two lanes could be provided on Albany eastbound towards Portland (at the expense of a few parking spots) to mitigate any queueing issues. (See cross-section F-F.)

Coming eastbound, two lanes would be provided approaching Albany, with the potential for the left lane to be a turn lane with an exclusive phase. These two lanes would continue past a floating bus stop (the bus would stop in the right travel lane, with the cycle facility running to the right of the boarding platform) widening to three past the Grand Junction. This would allow the right lane to serve buses and right turns exclusively (there are only about 15 right turns per hour, or one every three light cycles, so this movement is minimal) with the middle lane for straight traffic and the left lane a queue for left turns, which often have to wait for opposing traffic to clear. With such a lane, an exclusive left turn phase could be provided, as this is an important movement for traffic and for the EZRide shuttle. (See cross-section E-E.)

Albany Street to Sidney Street

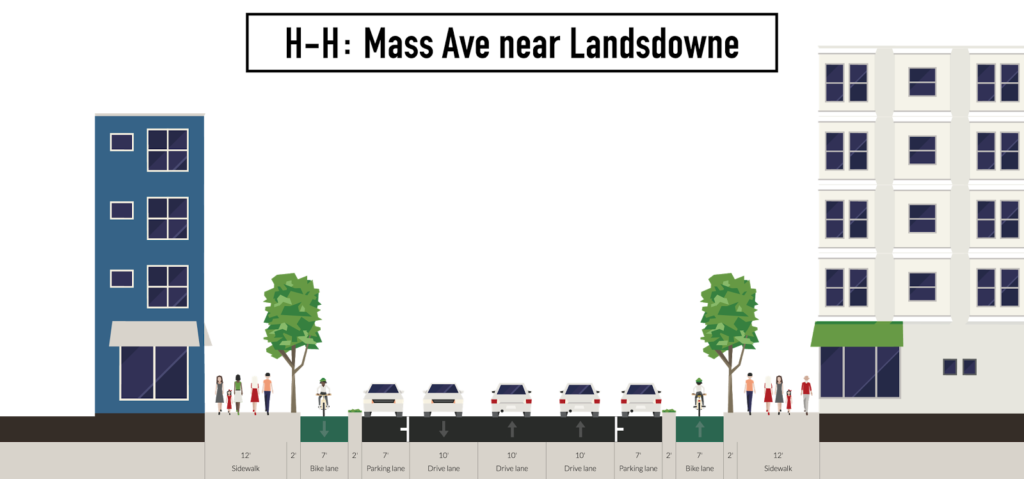

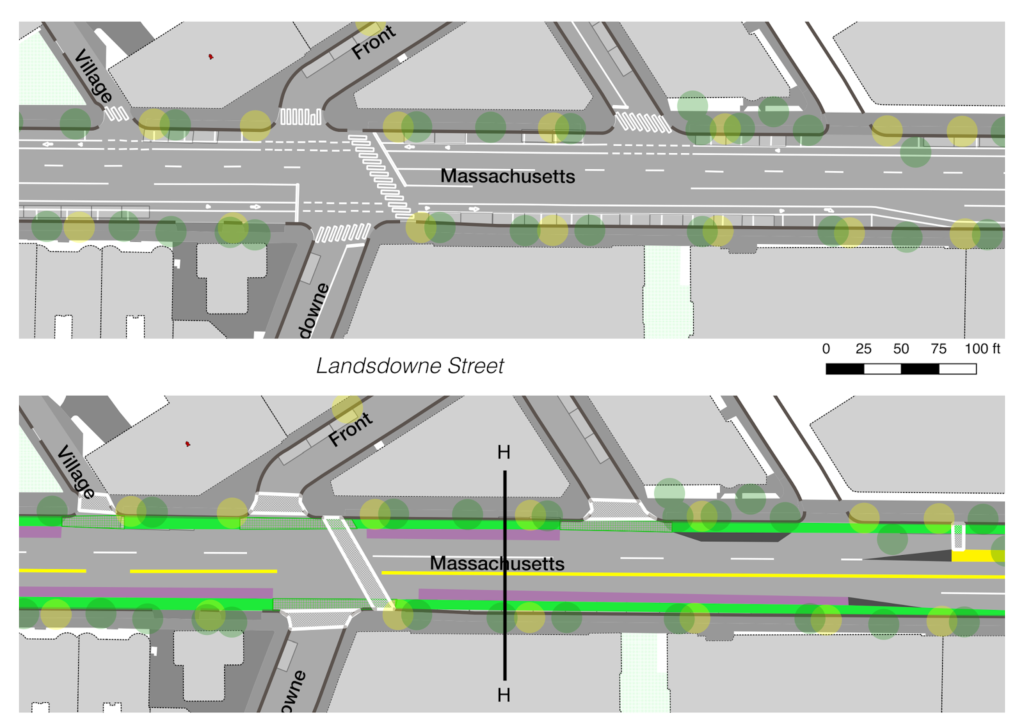

West of Albany Street, the corridor becomes much less complex, at least until Lafayette Square. Side streets are narrow and have little traffic, and there are few driveways to preclude the use of a protected bicycle facility on both sides. By moving the bike lanes to the right of the parking, the current layout of the roadway would be largely unchanged with two lanes westbound (where there are sometimes queues which form from Central Square) and one eastbound. Little parking would be lost. (See cross-section H-H.) This would be one of the easiest portions of the roadway to rebuild since few changes would take place other than protected cycling facilities, and could be done quite quickly to improve conditions for cyclists without major impacts to other users. One change that could be made would be to cut back the corner at Landsdowne and Mass Ave for right-turning traffic. This is the turn made by buses laying over on Franklin Street (and in this plan, more buses would use this layover) and it is a tight, acute turn for buses. If the gas station were bought or taken by the city (a similar gas station taking allowed the repurposing of Lafayette Square), it could be used as a pocket park in addition to providing a better turn radius.

Central Square:

Sidney Street to Inman Street

[If you’ve read my original post on Central Square, this uses a lot of it as its basis. There’s some new thinking here and updated graphics, but if you’re familiar with that post, you can probably skim over a bit of it.]

Central Square is complex. I often cite it as an example of the difficulties autonomous vehicles will have operating in urban environments; the number of human cues and interactions between the tens of thousands of users of Central Square—most of them not driving—is intense (this is the topic of another post entirely). The complexity and confusion of Central Square is its saving grace: traffic rarely moves fast enough to do much harm. Still, the roadway is often congested, it is no place for a beginner cyclist, vehicles frequently pull across the bike lane or make illegal U-turns, and that doesn’t even get in to the transit users.

|

| Transit on Green Street is frequently blocked by delivery vehicles. It shouldn’t be there in the first place. |

Central Square is, at its heart, a transit node. The Red Line below carries more passengers through the Square than all other modes combined, and as many passengers board and alight from the Red Line as vehicles pass through the streets above. It also serves half a dozen MBTA bus routes, and the MASCO shuttle, which collectively carry more than 30,000 passengers per day, with the bus stop on Mass Ave processing dozens of buses per hour. Most other such bus nodes and transfer points in Boston were built with some sort of separated subway-surface transfer facility like Harvard, Lechmere, Ashmont, Kenmore, Ruggles or Forest Hills, and former such facilities at Massachusetts (now Hynes) and the former Egleston station on the Washington Street Elevated. Not Central. Not only are bus passengers served by curbside stops, but some of these stops are along Green Street, a narrow street a block away. A new bus user would have trouble simply finding the bus stop, to say nothing of the luck needed to get a seat on a 70 bus at rush hour. (The geometry of these streets is not conducive to bus operations, notable are the poor “one way” sign at Pearl Street and Green Street, encased in a tube of concrete after too many chance encounters with the CT1 bus making a turn, and the 47 bus, which swings practically in to the opposing traffic lane to make the right turn from Mass Ave to Pearl Street.)

Yet if you look at a cross section of Central Square, it’s mostly used for cars and parking. Despite ample and inexpensive space available in nearby lots and garages, street parking is provided on both sides of the street. (This is the case despite the fact that the majority of users of Central Square likely arrive by foot, bicycle and transit.) The only exception to this is between Pearl Street and Prospect Street, where the curb plays host to a major bus-subway transfer point (and the City still finds curb space for loading zones and taxicabs). But Central Square will not be solved merely by trying to shove more uses through this already congested area unless we take a step back and look beyond Mass Ave, at which point there are some intriguing options.

For most of the length of Mass Ave, there is no useful parallel street. Unlike the grids of many cities, Cambridge’s streets, while mostly straight, run in any number of directions, rarely running parallel for more than a few hundred yards. Many gridded cities—most cities in the United States are built on some sort of grid—use “one way pairs” to better manage traffic (although sometimes to the detriment of the urban form) but the layout of Boston means such a scheme is basically unheard of. Yet, in a small sense, Central may be the exception, and this may provide an interesting solution.

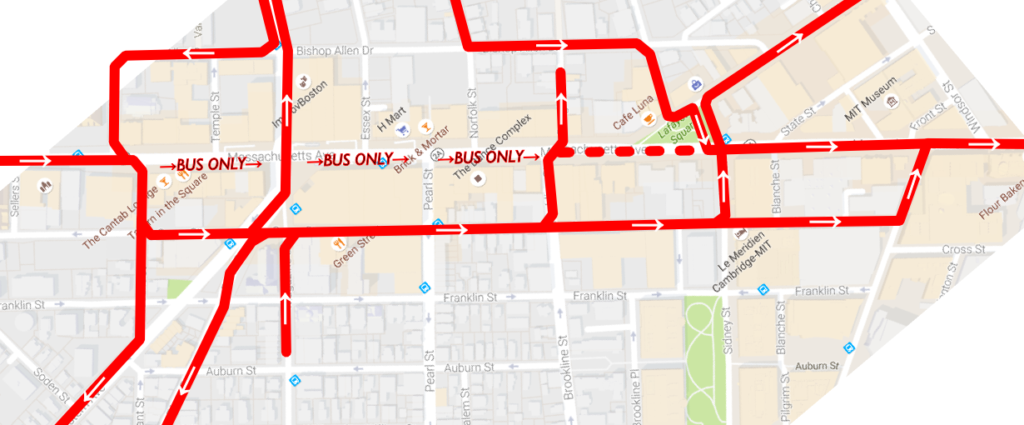

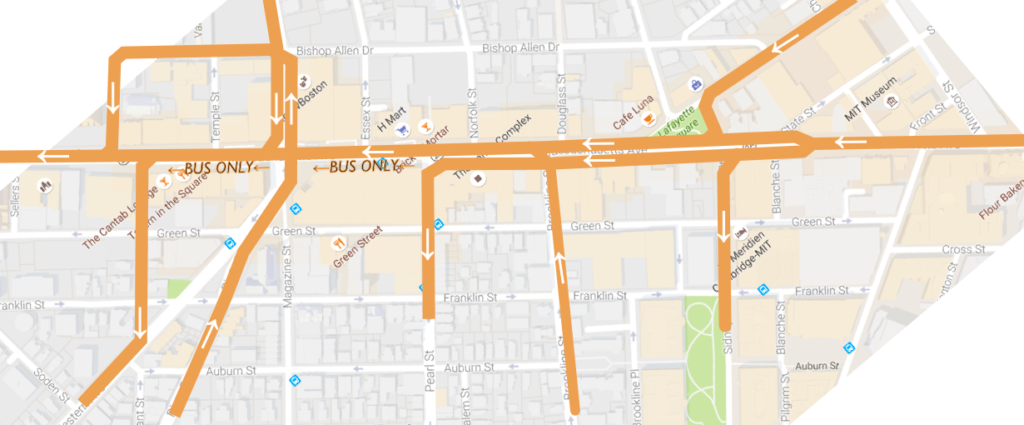

Between Landsdowne Street and Putnam Avenue, Green Street parallels Massachusetts Avenue for just shy of a mile. This distance may not seem particularly impressive, yet it is twice the length of any other street paralleling Mass Ave anywhere along its 16-mile route from Boston to Lexington. The section of Green Street west of Central Square is narrow and residential in character and adding significant traffic there would be difficult politically. However, from Pleasant Street east, there are only a few residences, and the street serves mostly commercial properties, as well as several bus routes. This post will argue that these bus routes should be relocated to Mass Ave to provide better connections and amenities, and that general eastbound traffic on Mass Ave should be relocated to Green Street, which will be reconfigured to run eastbound. While the number of vehicles will increase, hundreds of buses will be removed from the street daily, a sensible tradeoff for the abutters of the street.

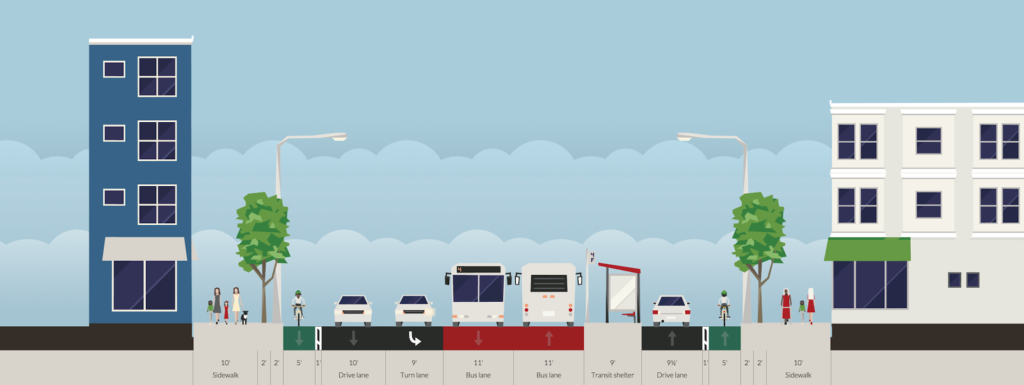

This, in a sense, would spread the users of Mass Ave across 140 feet of right-of-way (Green Street and Mass Ave combined), making Green Street an extension of Mass Ave. Westbound traffic would remain as is, and buses would use an exclusive busway through the center of the square, mitigating congestion and allowing passengers to transfer to and from the Red Line adjacent to the bus stops rather than forcing many to use inadequate stops on a side street. Eastbound traffic would be relocated to Green Street, allowing the two streets to serve, for a short distance, as a one-way pair, with the goal not to improve and increase traffic throughput, but to improve transit flows and safety for cyclists and pedestrians.

This can be imagined in several steps. Rather than moving intersection-by-intersection, I’ll detail the entire corridor, since it is being proposed as a major rethinking.

1. Green Street is rerouted to run eastbound. This allows all of the traffic from Mass Ave to be shunted south on Pleasant Street by the Post Office and then left on to Green. (Franklin would probably also be flipped from east to west, which would have the added benefit of eliminating the Franklin/River intersection, which has very poor sight lines.) Green would be two lanes wide, with one lane for through traffic and the other for deliveries and drop-offs and potentially parking between Magazine and Brookline, and turn lanes where necessary. The street is 24 feet wide, which is wide enough for two 12-foot travel lanes. The sidewalks would remain as is, with significantly less use since they would no longer be used for bus stops (the bus stops are frequently so crowded that pedestrians are forced to walk in the street).

Once past Pearl Street, traffic would be able to filter back to Mass Ave. Some traffic would take Brookline Street, mostly to zigzag across to Douglass Street and Bishop Allen. Some traffic destined to Main Street could turn here but most would continue east to Sidney or Landsdowne. At Sidney, signals would be changed to allow a straight-through move on Sidney Extension to Columbia and Main, and there would no longer be a left turn allowed from Mass Ave to Sidney Extension. (This would be the new hazardous materials detour for traffic unable to pass through the downtown tunnels.) Traffic going towards Boston could continue on Green Street as far as Landsdowne, where the diagonal street allows for less severe turns.

Eastbound traffic on Green Street is preferable to rerouting westbound traffic via Bishop Allen, for several reasons. First, it’s probably good from a political and practical sense to have some vehicular access to Mass Ave, so only one direction of traffic should be rerouted. Otherwise you wind up with some dead-ended narrow streets abutting the square. Complete streets include cars. They just don’t make them the priority. Second, the right turn for through traffic from Mass Ave to Bishop Allen would be very hard to figure out; the Sidney Extension-Main-Columbia turn would be implausible with increased traffic. Douglas Street is only 20 feet wide and is probably too narrow for trucks. Norfolk is 24 feet wide, but then you’re creating a busy turn right in the middle of the square.

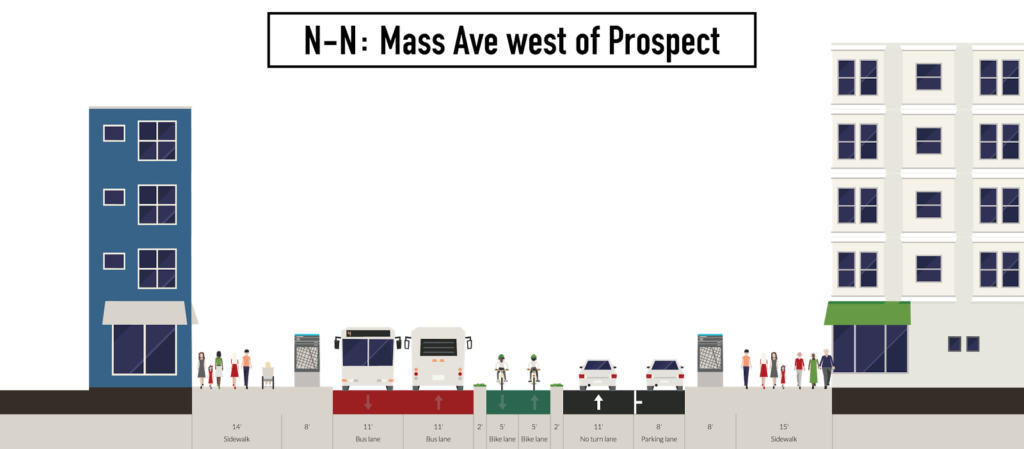

2. Mass Ave eastbound is rerouted to Green Street. As described above, all traffic from Mass Ave eastbound would be diverted to Green Street at Pleasant. Traffic wishing to turn left on to Prospect would take a right on Pleasant, and a left at Western, which is the current traffic pattern. Light timings would be changed at Western to allow for additional traffic, although they are already optimized for north-south traffic, which is significantly higher than east-west traffic on Mass Ave. The current right-turn lane from Prospect to Mass Ave would be repurposed as a bus-only lane. Mass Ave westbound would remain mostly is.

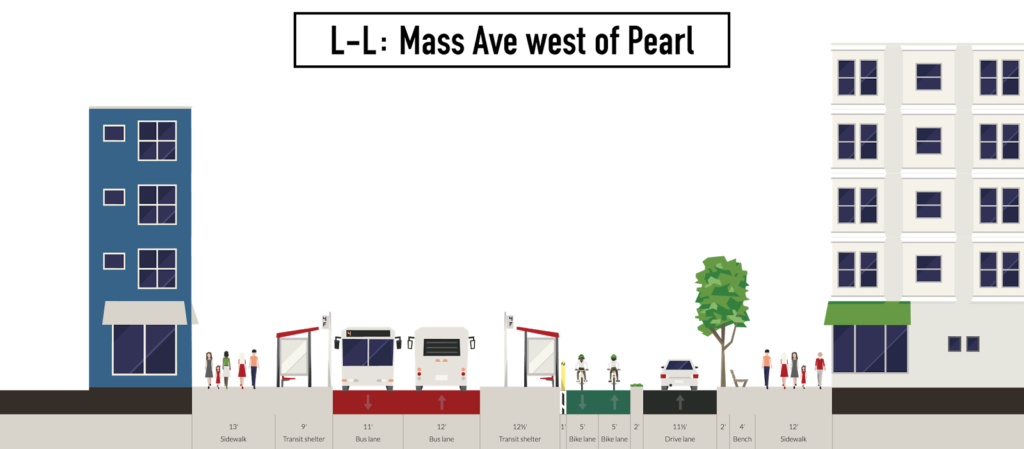

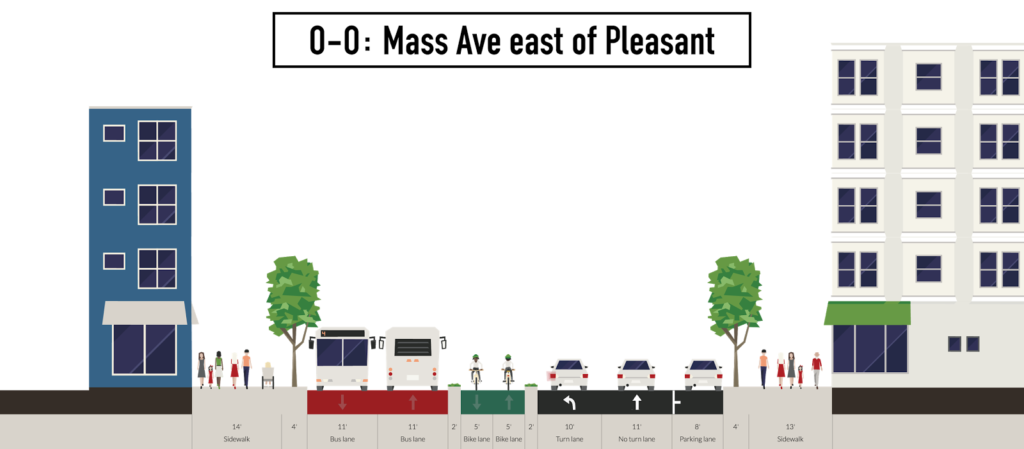

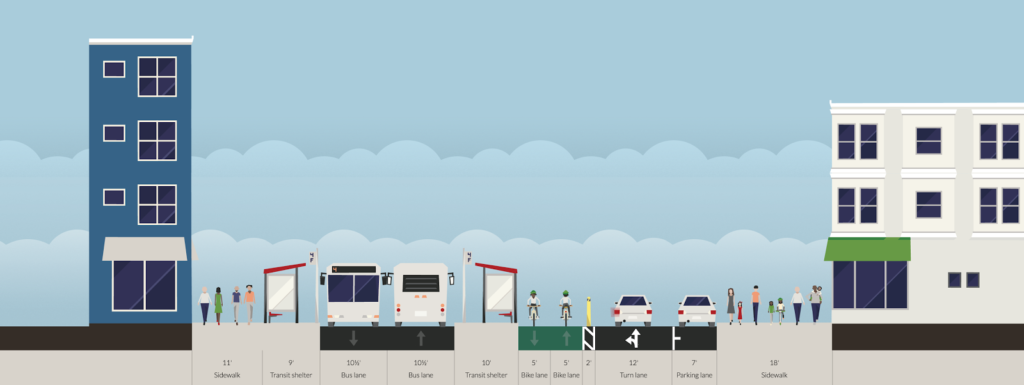

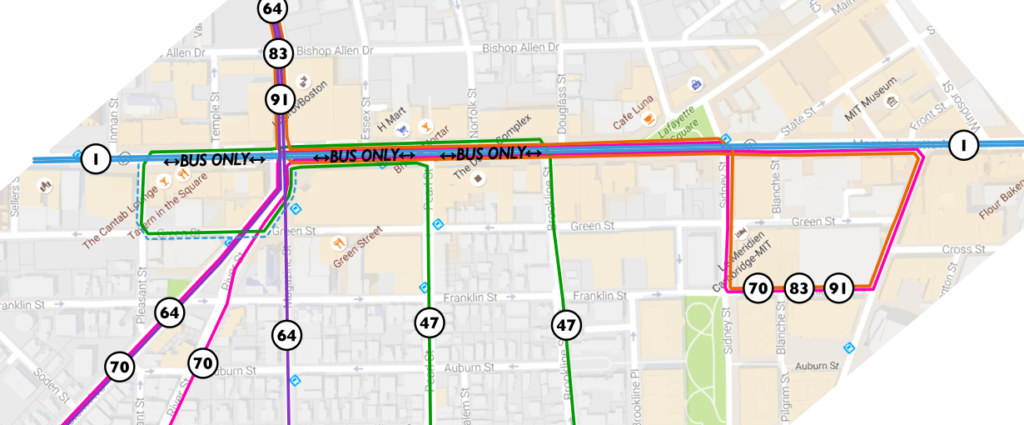

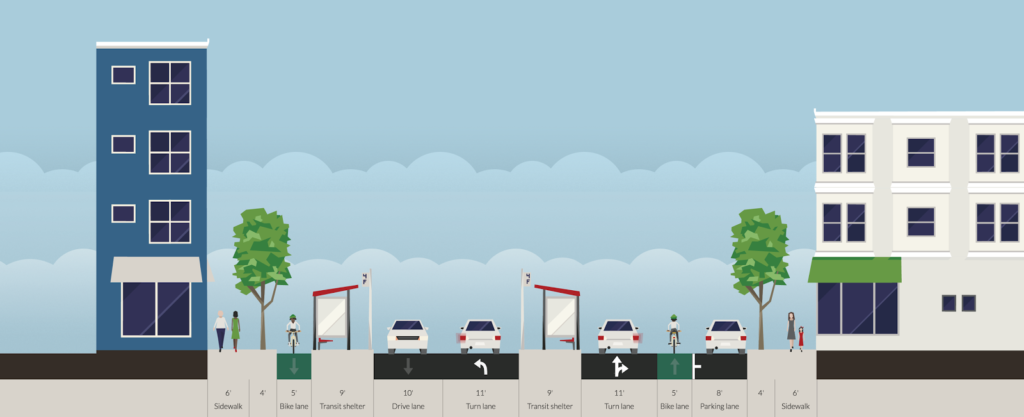

3. A two-way busway would be built on the south side of Central Square from Pleasant to Sidney. Eastbound buses would be exempt from the turn to at Pleasant to access Green Street and instead proceed directly down Mass Ave. East of Pearl Street, this busway would allow for some general traffic: right turns from Brookline Street to Mass Ave and left turns from Mass Ave to Pearl. (See cross-section K-K.) The busway would also allow emergency vehicles (including from the nearby firehouse) to bypass gridlock in Central Square, creating BRT elements in one of the most congested areas of the 1 bus route (as opposed to, say, the Silver Line in Roxbury, which has bus lanes on the least congested part of the route but in mixed traffic in the most congested areas). Bus stops would be consolidated between Pearl and Essex for both better access to the Red Line and to ease confusion about which buses stop in which stops: with the exception of the rush-hour 64 bus extension to Kendall, all buses would stop in the same location. This 160-foot long section could accommodate four 40-foot buses at the same time. (See cross-section L-L.)

Since Central is a terminal for most routes, buses are required to turn around, and would be able to loop as follows:

- 1 is a through route. The CT1, which should be consolidated in to the 1 bus since recent stop elimination have made the routes mostly redundant, could loop via Pleasant-Green-Western.

- 47 would go left from Brookline to the busway. Its loop and layover would be made via Pleasant-Green-Western. A single-bus layover would be retained at the end of Magazine Street. This would eliminate the need for passengers to walk a block to transfer.

- 64, when not operating through to Kendall, would loop via University Park, but instead of serving stops on Green Street, it would loop back to the busway. Left turns would be allowed for buses from the Mass Ave busway to Western.

- 70/70A would loop via University Park as above, making inbound and outbound stops on Mass Ave, eliminating the walk to Green Street and the inadequate boarding facilities there

- 83 and 91 would use a left-turn lane for buses only on Prospect Street (this is currently a painted median; the 30-foot-wide street would allow a bus lane here) to allow access to the busway. An actuated signal there would allow a left turn phase when necessary (approximately ten seconds every ten minutes, which would have a negligible effect on other traffic). Buses would then loop and layover in University Park like the 70. This would allow these routes to serve the growing University Park area, which has seen significant redevelopment in recent years.

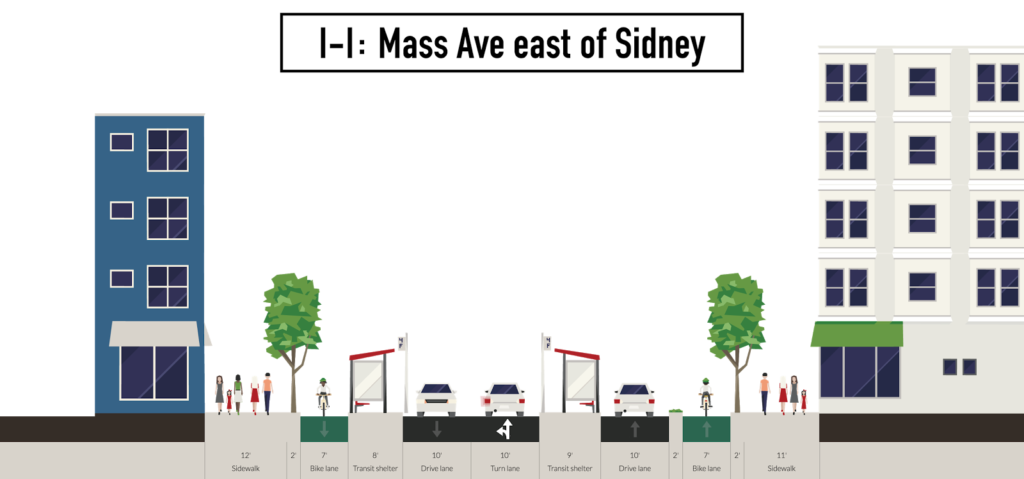

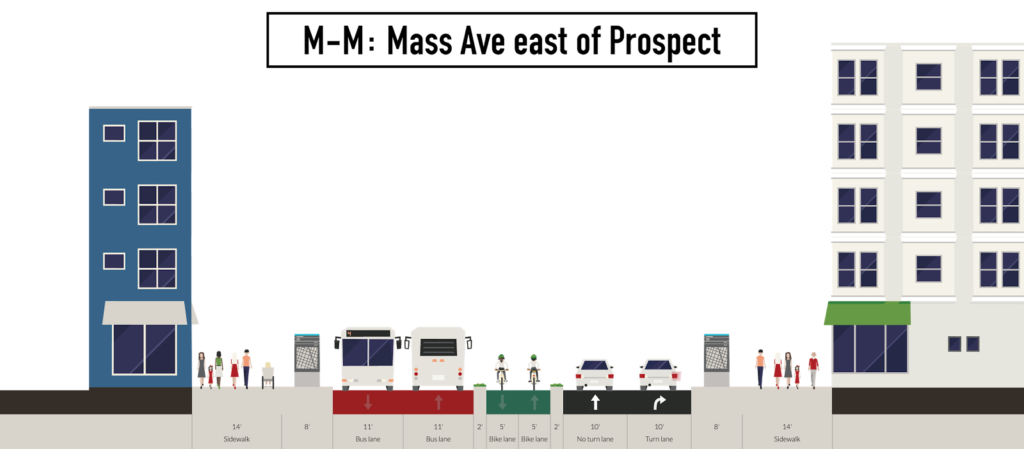

4. Eastbound bus stops would remain largely where they are on the south side of Mass Ave, but any pull-ins and bulb-outs would be removed to allow vehicles to maneuver more freely. (The additinal crossing distance would be mitigated by the bus platform mid-street; see cross-section L-L.) Westbound bus stops would be placed in the center of the roadway; one between Pearl and Essex (approximately 160 feet long) and another east of Sidney Street (60′ long, for the 1 Bus only; more on the Sidney Street intersection later on, see cross-section I-I), where those buses (and general traffic turning left on Sidney and Pearl streets) would be shunted to the left of the floating bus stops. These stops would be ten feet wide at Pearl Street and eight at Sidney, significantly wider than the current stops on Green Street, and built with modern amenities and shelters. The 1600 square foot bus stop at Pearl Street would provide waiting space for 400 to 500 passengers at three to four square feet per passenger (see MBTA crowding policy). Pedestrians transferring between the Red Line and westbound buses would have to cross just the westbound traffic lanes of Mass Ave, no longer making the trek to and from Green Street. West of Essex Street, the bus lanes would jog to the right to allow clearance between the head house and elevator for the main entrance to the Central Square station. (See cross-section M-M.) The bus platform—which could be raised to allow level boarding akin to the Loop Link in Chicago—would span the distance between the Pearl and Essex crosswalks, allowing access from both ends of the platform. (The sidewalk/bus platform for eastbound buses would also be raised to allow level boarding.) The MASCO shuttle would also use this corridor.

5. In between the westbound bus stop and the westbound traffic would be a 10- to 12-foot-wide center-running protected bicycle lane, running from Sidney to Inman. Except where adjacent to the firehouse, it would be raised above grade and separated from traffic; most minor cross streets would allow only right turns to and from Mass Ave. At either end, a separate bicycle signal phase would allow cyclists to move from existing bicycle facilities to the center of the roadway (more on this in subsequent section). This would eliminate the constant conflicts between cyclists, motorists and buses. Bicycle traffic calming measures would be required in the vicinity of the bus stop at Pearl Street with high pedestrian traffic, but cyclists would otherwise have an unobstructed trip from Sidney to Inman (with traffic lights at Brookline and Prospect, where a bicycle phase or two-stage turn boxes might be necessary for right turns). For turns to Prospect and Western, bike boxes would be provided to allow two-stage turns. For turns to minor streets, cyclists could use areas adjacent to crosswalks to move between the PBL and the curb. Since bike lanes in Central Square are frequently blocked by vehicles, this would wholly eliminate these issues.

Why not side-of-street PBLs, which are generally considered to be best practice? A few reasons:

- Red Line head houses. If it weren’t for the location of the Red Line head houses, it would probably make more sense to have side bike lanes, but we should assume that the Red Line infrastructure are immovable and constrain the width of the street in this area.

- Right turns. While turns from the bike lane to adjacent streets are somewhat more difficult for cyclists, putting the bicycle facility in the center of the roadway eliminates right-hook turn hazards.

- Bus-Subway transfer passengers. Since Central is one of the busiest bus-subway transfers in the MBTA system without an off-street facility, it requires large bus stops to accommodate passengers (the current stops are grossly inadequate). To accomplish this, it would need to pull the cyclists far back from the street, which would create more severe turns to allow the cyclists to clear the head houses on one side and the bus stops on the other. Since the eastbound stop is busier for waiting passengers—handling boardings for the 1, CT1 and 47, which at peak times account for a full busload of passengers every three minutes—floating it would require a larger bus stop than the westbound stop (which, at peak boarding times, only serves the 70, 83 and 91, and a few 1 bus passengers traveling from Central towards Harvard). Integrating the eastbound stop with the sidewalk allows for more overflow.

- Pedestrian traffic, especially between the buses and the subway. A successful PBL would need significant separation from the sidewalks to avoid becoming choked with pedestrians. In high-pedestrian areas, this is easier to accomplish in the middle of the road than it would be alongside the sidewalks; since this proposal separates the eastbound bus stop from the bicycle facility. Passengers moving between the outbound Red Line and 70, 83 and 91 buses will have to board at a station adjacent to the PBL, but there are fewer of these passengers than those waiting for the 1, 47 and CT1 in the morning.

- The busway creates the need for a buffer between the westbound travel lane and the buses, which is a good place for the cyclists; with side-running lanes it would require additional buffer space on each side. It does create two points of conflict on either end of the PBL to transition from the existing lanes (which are already at signalized intersections, so it would require only a short additional phase) but otherwise have relatively clear sailing for cyclists devoid of the current maze of turn lanes, parking spaces and taxi stands.

- Finally, side-of-street bicycle facilities would mostly preclude the use of curb space for vehicles, which is necessary for loading, pick-up and drop-off zones in Central Square.

It’s worth noting that there were similar challenges in placing bicycle lanes near North Station, with extremely high pedestrian activity, as well as bus and shuttle drop off areas, and the solution there was similar: to put the bicycling facility in the center of the street. There are even lights now in operation which allow cyclists to cross from a side-of-street facility to the center, much the same as would be required in Central.

The bicycle facility could be placed on an adjacent street, but this would be both a practical and optical detriment of cyclists. As a practical matter, it would require cyclists to take a longer and less attractive route, causing cyclists to use other modes. It would also make it harder for cyclists to reach the businesses in Central Square, which do not generally front on to Bishop Allen or Green streets. From an optics standpoint, it would once again show that the street was designed first for motorists, with cyclists an afterthought. In any case, many cyclists would ignore lanes on a parallel street leading them to travel in shared vehicular lanes in Central, which would solve little.

Beyond Green Street and Bishop Allen, there are few if any parallel streets to accommodate cyclists. The nearest such street is Broadway, which runs from Harvard Square to Kendall, which would require cyclists destined for the Harvard Bridge to detour to the point that most cyclists would likely vote with their feet and stay on Mass Ave, even if it were more dangerous. Other streets, such as Broadway, also traverse more residential areas, with many more driveways and which would require the removal of significant residential parking to install bicycle facilities, a bit third rail of Cambridge politics.

6. The westbound lanes of Mass Ave would be 20 to 24 feet wide, allowing the current travel lane as well as a wide area for a loading zone for area businesses, a taxi stand and other pick-ups and drop-offs near the transit station and, in places, a wider sidewalk. (This is also a width required by the fire department.) These uses would no longer conflict with bicycle traffic in an adjacent lane. Some street parking could be provided, but it is probably best relegated to side streets nearby or parking lots (there are generally few on-street spots today). It is important to provide loading zones, as the businesses in the area do need service from suppliers which often have little choice but to use the bike lanes to load and unload today. Separating the bike lanes, and providing specific loading facilities, will remove this as an issue.

Central Square Signals:

Mass Ave and Sidney

The two intersections at either end of the treated area will both need to be reconfigured and retimed to allow traffic throughput as well as transition cyclists and buses between in and out of the mid-street bike facility and busway. The intersection at Sidney Street was rebuilt in the late 2000s and despite its complexity, it by-and-large works. The best feature of the intersection isn’t even the roadway itself but the adjacent plaza, Jill Brown-Rhone park. What was once a sea of asphalt and a gas station is now one of the best-used parks in the city. From frequent dances, bands and the omnipresent consumers of Toscanini’s ice cream (currently relocated to East Cambridge for the redevelopment of its building), the park is a testament to what can come from the reappropriation street space for a different use.

Currently, the Mass Ave and Sidney intersection has three light phases, one for traffic going straight on Mass Ave, a second for traffic going straight on Sidney and a third of left turns from Mass Ave east to Sidney Extension and Mass Ave west to Sidney, and corresponding right turns (the right turn from Sidney north to Mass Ave east is the only movement allowed from Sidney). These phases are coordinated with the light at Main, Sidney Extension and Columbia to mitigate queueing on the short piece of Sidney Extension. These phases would have to change to allow for a bicycle cycle to move cyclists between the right-side PBLs to the east of Sidney and the center PBLs to the west. This phase could be quite short—perhaps only 10 or 15 seconds—as many cyclists can cross the intersection in a few seconds. At the same time, cyclists from Mass Ave could make turns on to Sidney Street, and the right turn from Sidney Extension to Mass Ave west could be allowed for motorists.The proposed phases are as follows as a 75 second cycle:

- Straight-through vehicular traffic on Mass Ave and Main Street, broken in to three streams by the floating bus stop (westbound traffic, buses and Pearl Street turns, eastbound traffic). Concurrent walk signals on Mass Ave, with right and left turns allowed (turn traffic is relatively low). The only restricted turn would be the left from Mass Ave east to Sidney Extension, which would not be allowed at any time (traffic from Mass Ave to Main or Columbia would mostly be on Green Street and could use the straight-through move on Sidney). This phase would last about 25 seconds

- Straight-through vehicular traffic on Sidney Street. The current vehicle-bike-vehicle lane on Sidney Extension south would be retained, but the right side bike lane would be eliminated and cyclists would be allowed to continue straight on Main and cross the plaza in a designated area. (More information about this below.) Unprotected turns would be allowed between Sidney and Mass Ave with concurrent walk signals. Main Street westbound would also have a straight signal on to Columbia. This phase would probably last about 25 seconds.

- The bicycle phase on Mass Ave would allow cyclists to move between the side PBLs and the center PBL on Mass Ave. Concurrent walk signals east and west on Mass Ave. To clear traffic from Sidney Extension queued from phase 2, a left turn from Sidney to Columbia would be signaled, and a right turn across an active sidewalk (this is currently the phasing structure). Adjacent right turns from Columbia to Sidney Extension would also be permitted. This short signal would be only long enough to clear any queues from Sidney on to Main/Columbia, probably only about 10 seconds.

- A fourth phase would be necessary to provide a crossing of Columbia west of Sidney Extension. At 3.5 feet per second this would require 13 seconds of crossing time. The bicycle crossing on Mass Ave would remain active, as would the crosswalks in Phase 3. At 15 seconds, this would provide a combined phase of about 25 seconds.

Perhaps the trickiest current movement at Lafayette Square is the left-right movement for a cyclist from Main Street to Mass Ave. Thanks to a citizen request (guess which citizen), a bike box was installed at the end of Main Street to allow a cyclist to move in front of traffic and prepare for the turn; otherwise a cyclist is required to take a left across a stream of traffic. The cyclist then uses the right hand turn lane to make a sharp, sweeping turn on to Mass Ave, often with car traffic immediately to the left. This could be reworked by allowing cyclists to proceed straight on Main Street and across the plaza (a shared roadway here could also accommodate fire apparatus pulling out of the firehouse and, in the long term, buses from Mass Ave to Main Street if the 70 were ever extended to Kendall Square, as some plans propose).

A bike crosswalk would have to be installed adjacent to the crosswalk across Columbia to allow cyclists to make this maneuver (non-standard, but not-unprecedented and doable in this context), as well as adjacent to the crosswalk to the PBL at the west end of the plaza. It could be coupled with a limited-use lane for firetrucks to cross over the park area in emergencies, but would otherwise be a shared space. Some cyclist calming would be in order as well (ramps would help this) as this is a high pedestrian area. There is a similar facility with a bicycle-only crossing of a sidewalk at the corner of Concord and Garden streets west of Harvard Square. Here, this would allow cyclists to take a safer, more direct route, and also allow a green light for vehicles during part of the bicycle phase at Mass and Sidney to clear out right-turning queues on Sidney Extension.

Mass Ave and Inman/Pleasant

The other end of the treated area is a bit more congested than Lafayette Square, with all traffic on Mass Ave taking a right on Pleasant and Inman feeding across to Pleasant as well. However, the signal phasing is much easier than at Mass and Sidney. The current phase has a straight movement for Mass Ave, a turning movement for Inman Street in both directions and an all-walk signal for the crosswalks. This would largely stay the same, with a couple of added signals and phases. This is planned for approximately 90 seconds.

- Inman southbound right and left. All vehicles southbound on Inman going left would be forced to turn right on to Pleasant. If Pleasant were striped with two parallel lanes (at 25 feet wide, it is plenty wide enough, but would require removing four parking spots) this would allow traffic to turn concurrently from Mass Ave west and Mass Ave east on to Pleasant. This adds a signal for the current unsignaled turn from Mass Ave west to Pleasant Street south. (20 seconds)

- Bicycle phase between the side-PBLs and the center PBL. During this phase, buses could also turn left from the busway on to Pleasant Street. This is required for the 47 and CT1 buses. (20 seconds)

- Walk phase for all crosswalks. At this time, westbound buses (1 and MASCO) would cross diagonally from the westbound busway to the eastbound travel lane, but then wait at the crosswalk for the next phase, a queue jump to allow them to leave the busway ahead of adjacent westbound traffic. (20 seconds)

- Westbound and eastbound traffic on Mass Ave. Eastbound traffic would turn right, except for buses which would continue straight in to the busway. (30 seconds)

- This actuated phase would allow a bus arriving during phase 4 to make the diagonal crossing and continue through the light, while still allowing eastbound traffic to make the turn on to Pleasant Street. (10 seconds, borrowed from Phase 4, if actuated).

There is potential for reduced throughput at this intersection and would have to be modeled—especially on Mass Ave—but it already has lower traffic than areas to the east. Two lanes are provided westbound because of this reduced capacity. It may be necessary at this location—and at Pearl Street—to install a gate to minimize the number of errant drivers in the busway, although the bus layover at Magazine Street and Green Street is seldom-if-ever used by vehicles as a straight-through move from Magazine to Prospect.

Other Intersections

There would also be changes to other intersections along the corridor. Western and Prospect would remain mostly unchanged, although buses would be allowed to make the left turn on to Western for the trip west. There would be the addition of the short bus-only left turn lane from Prospect to Central Square for the 83 and 91 buses, this would be actuated by the buses and would only require one ten-second cycle approximately every ten minutes, less than 2% of the overall throughput of the intersection. The only other street which would allow access across the PBL would be Brookline Street, which would otherwise remain unchanged. Finally, the left turn from Mass Ave to Pearl Street, which is currently an unsignaled turn from an exclusive turn lane, would remain unsignaled, with cars turning left and buses continuing straight. Depending on compliance, a gate may be necessary to keep cars out of the busway (although enforcement by Cambridge and Transit police may keep drivers from erring, some drivers unfamiliar with the area may follow a bus in to the busway despite any number of signs).

Green Street would have to be resignaled as well. The current intersection at Western/River/Magazine may become less complex, as traffic which currently has to merge out of Magazine and Green with a very short queue before the light would be turned. Pearl and Green streets would remain a four-way stop, and four-way stops or signals may be required at the Green Street crossings of Brookline and Sidney due to increased traffic. However, several intersections on Mass Ave in Central Square currently operate without signals, and this may be possible on Green Street as well.

Implementation Strategies

The sorts of changes proposed here would be a sea change for Mass Ave in Cambridge, and would likely have both broad support and broad opposition. Unfortunately, Cambridge frequently bows to opposition (and any sort of change), such as reneging on bicycle facilities on Pearl Street because of a few complaints about parking spaces. It would thus be important to work with transit and bicycling groups as well as business and community stakeholders to build a coalition of support for this sort of project before implementation. Working with other stakeholders would be imperative as well. MIT controls much the property on both sides of the corridor east of Sidney Street and while it should, in theory, be in the Institute’s best interest to promote safer and more efficient traffic, they must be involved from the start. MIT would lose about three quarters of the parking in front of the main entrance at 77 Mass Ave, but considering the mode share of visitors to campus (the majority coming by foot, bicycle or transit) it is anachronous to have most of the space in front of the campus devoted to a few parked cars.

The most drastic changes, however, take place in Central Square. Rather than a single owner, the Square is home to many businesses, large and small, and some would certainly bemoan the loss of a single parking space in front of their business. (This is despite the fact that businesses regularly overestimate the number of customers arriving by car and underestimate other modes.) A concerted effort would be required to assure businesses that deliveries could still be made (by designating convenient loading zones on Mass Ave and adjacent streets) and that patrons could still arrive by car, but that nearby parking lots and the Green Street garage would be a better option. The City could even promote use of the garage during construction with short-term discounts for parking there. Working with City staff, committees and the City Council would be important to put forth a united front for improving Mass Ave in general and Central Square in particular.

The hardest of these groups to organize will be transit users. While pedestrian and cycling advocates have longstanding interest groups and city committees, the City’s transit committee is much younger, as are groups such as TransitMatters and LivableStreets representing the interests of transit users. Meeting with those groups and selling the idea of a signature infrastructure improvement in Cambridge prior to public plans would allow for mobilization of transit users interested in a better experience, rather than letting the conversation get hijacked by parking interests as is so often the case.

Finally, the City should view this as an opportunity, not a threat. In 2015, the organization People for Bikes named the Western Avenue Cycle Track the best new cycling infrastructure in the country, despite the objections of some City Councilors, who worried that narrowing the street would cause increased traffic congestion (it has not). Western Avenue should be a blueprint for Cambridge, and rebuilding Mass Ave would be a connecting piece of infrastructure on a grander scale. If Western Avenue was named the top new cycling infrastructure in the country, imagine what the impact of a forward-thinking, transit-bicycle-pedestrian priority Mass Ave as a showpiece of the future of Cambridge in the 21st Century.