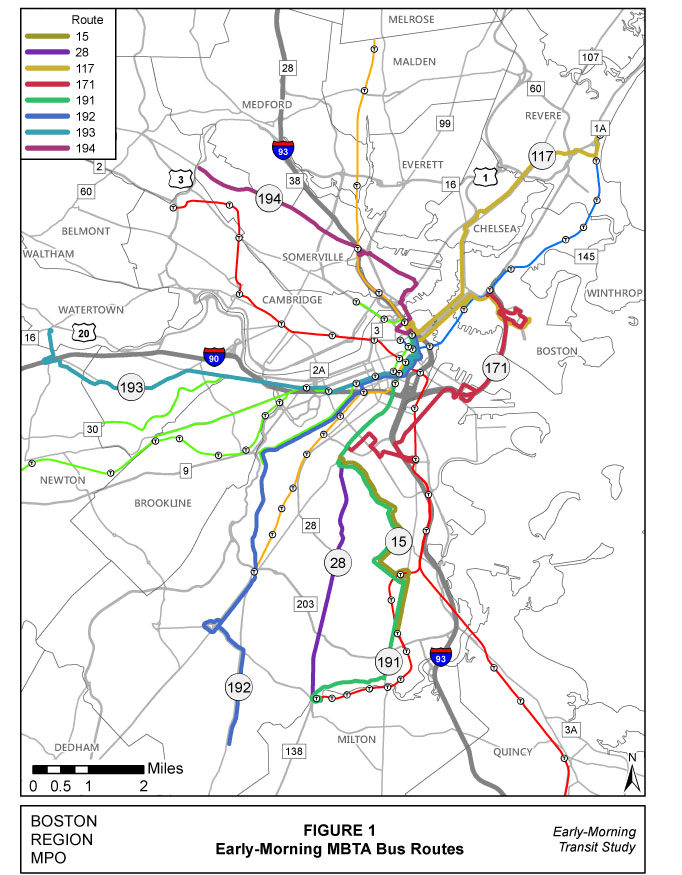

A study of early morning service

conducted by CTPS (MassDOT’s Central Transportation Planning Staff) in 2013

found these services to be well used. Indeed, there was extreme overcrowding

on one route: the single 117 trip (Wonderland-Haymarket) carried 89 riders. In

response, the MBTA added two additional trips as well as earlier trips on Bus routes

22, 23, 28 and 109.

|

|

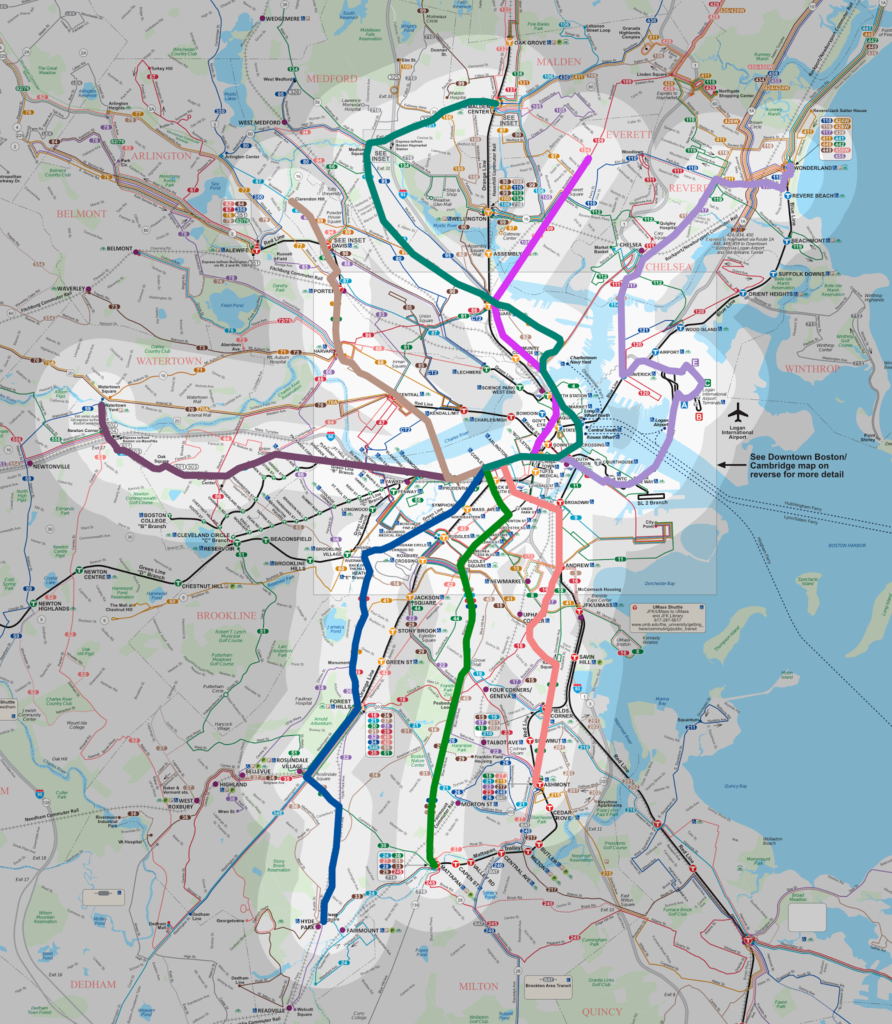

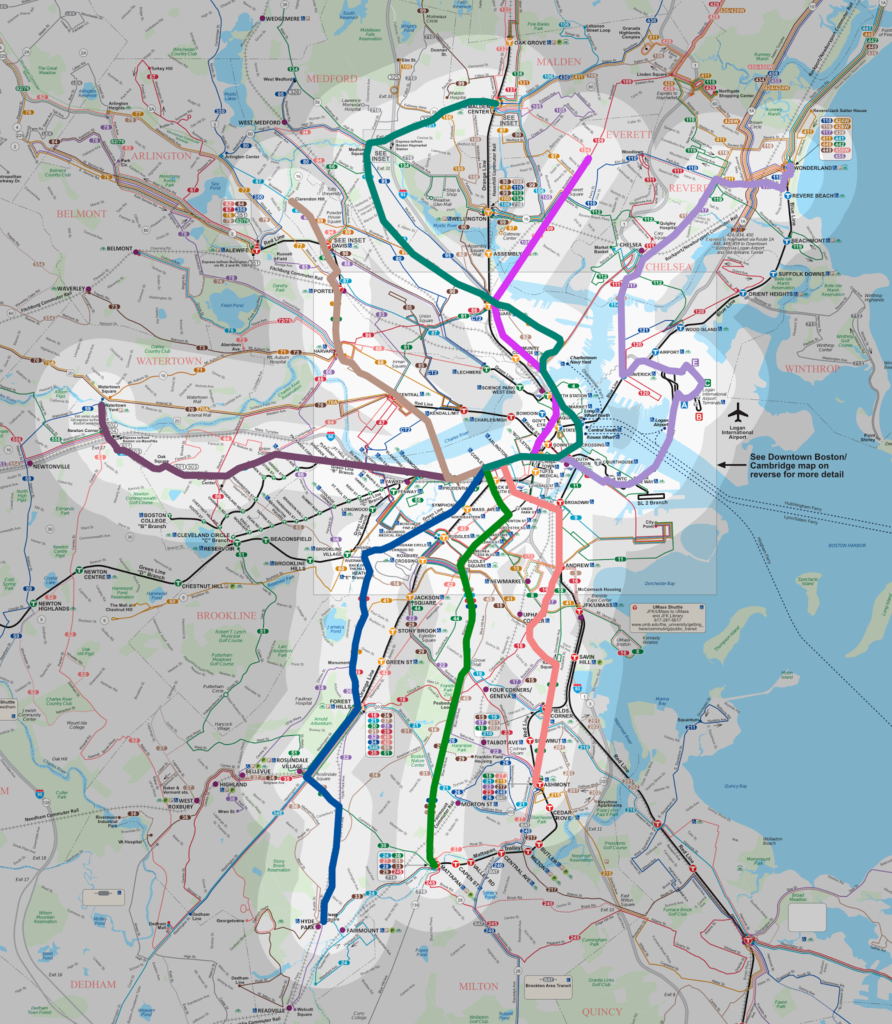

This map shows ½ and 1 mile buffers of the proposed late night

network superimposed on the T’s current route map.

See a full-size map here. |

This proposal would use these

trips (with some minor changes) as a baseline for a new, more robust

“All-Nighter” service. This would allow the use of current MBTA bus stops and

routes, and be mostly an extension of current service, not an entirely new

service. It would provide service to most of the area covered by MBTA rail and

key bus routes. The changes include:

- The primary connection point would move from

Haymarket to Copley. This significantly shortens many of the routes and

avoids time-consuming travel through downtown Boston to Haymarket,

allowing a single route to operate with one vehicle instead of two, thus keeping costs down. In

addition, Copley is somewhat more central to late night activity centers.

- The current early-AM routes provide good coverage

near most rail and “key bus” corridors with the exception of the Red Line

in Cambridge and the Orange Line north of Downtown. (This plan does not address the longer branches to Braintree and Newton which serve lower-density areas which would have lower ridership and higher operation costs.) To fill these gaps the

Clarendon Hill route would be amended north of Sullivan Square to follow

the route of the 101 bus serving Somerville, Medford and Malden. A new

route would be added following Mass Ave along the Red Line/Mass Ave

corridor to serve Cambridge, then run through Davis Square and terminate

at the Clarendon Hill busway.

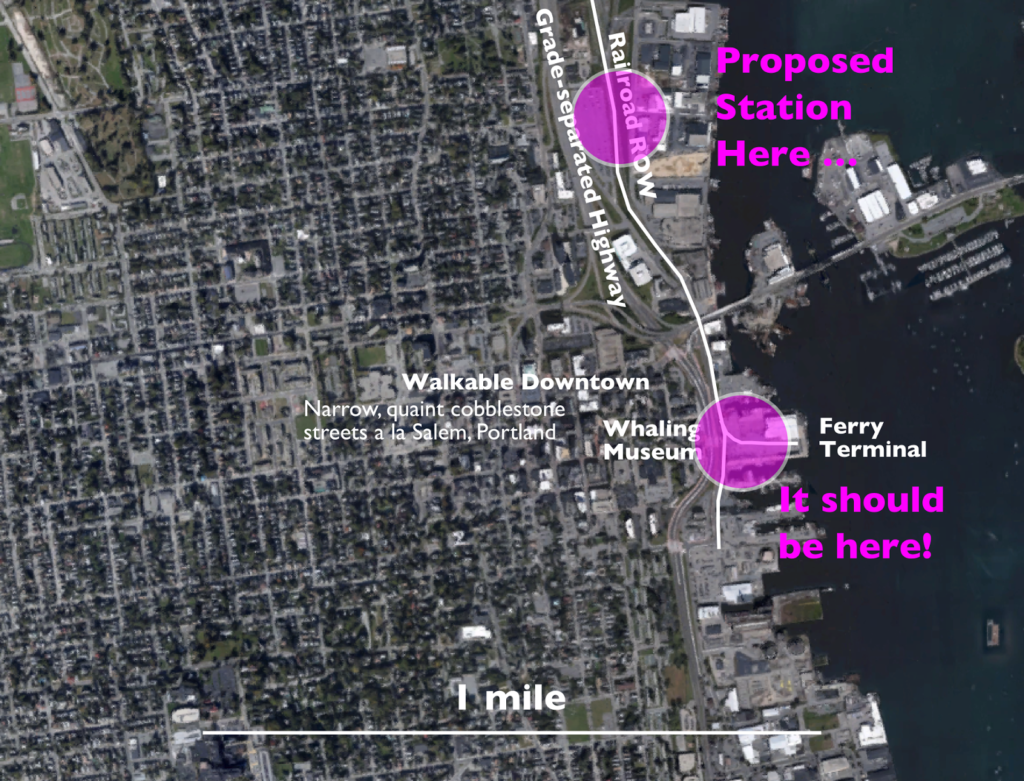

- A separate service would be run from Copley to

Logan Airport. It would follow surface streets from Copley to South

Station and the Seaport making local stops, use the Ted Williams Tunnel to

the airport, and then terminate at the Airport Station, where it would

allow connections to the 117 bus, which would terminate there rather than

Copley. This bus could be operated or funded by MassPort in partnership with the MBTA, much like the Silver Line, since it would directly benefit the airport. This service

could be through-routed with the 117 bus to Wonderland via the airport,

which wouldn’t require additional buses and would eliminate a transfer.

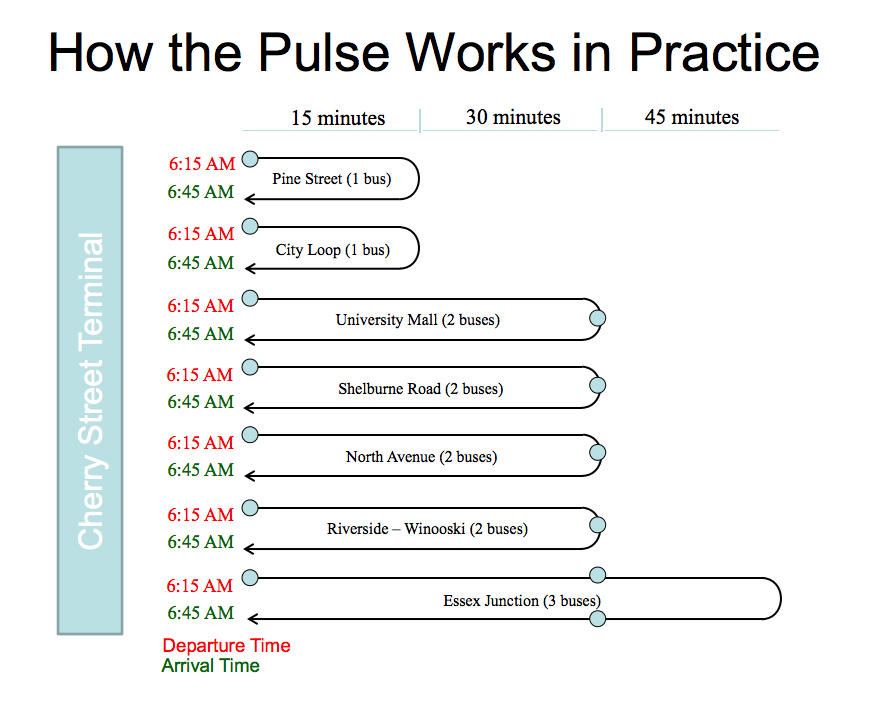

- Hourly service would operate on all routes, with

a “pulse” connection at Copley. (What’s a pulse? Here’s the answer.) All buses would be scheduled to arrive at

approximately :25-:28 past the hour and depart at :32-:35 past, allowing

customers to transfer between the various lines at this time. A dispatcher

could hold buses to make sure passengers could connect between lines. With hourly headways, a timed and guaranteed connection is required to provide any network effect and allow access between routes.

- Cities served by these routes could set traffic

lights to “flashing yellow” for the routes between midnight and 5 a.m. to

best accommodate schedules (this is already the case on many of these

corridors).

- Buses to the airport would allow employees to

arrive a few minutes before the hour, in time for shift start times, and

would then make a second loop through the airport to pick up employees

finishing shifts a few minutes past the hour.

- Airport buses would also allow overnight

travelers to make their way to downtown by foot, bicycle, Hubway, taxicab

or TNC (Transport Network Companies like Uber and Lyft), and make the

“last mile” to Logan on a bus. This is especially important for

late-arriving flights to the airport at times when there are often few

cabs available. The MBTA could explore public-private partnerships with

TNCs or other providers to bring customers to Copley Square to access

all-night service.

- The :30-past pulse time would allow workers

finishing shifts on the hour to access buses to Copley, or walk to Copley

itself, for connections to their final destination.

This service, based on current

late-night and early-morning published schedules, would require 10 vehicles for

four hours (approximately 1 a.m. to 5 a.m.), or 40 hours of service per day (with an extra hour on Sundays). At

this time, the MBTA operates approximately 10 hours of service covering the

early-AM routes, so the net hours of service would be 30. In addition, these

trips could be added to existing shifts, so rather than a deadhead trip between

a terminal and garage at the beginning or end of service, they would utilize a

bus already in service, saving an additional 6 hours (approximately) of

service, so the net hours per day would be 24.

Assuming a marginal cost per hour

of service of $125 (since this service would require no new capital equipment or vehicle storage, because

most of the bus fleet lies idle overnight, the full cost should not be used for

these calculations), this would cost approximately $1,095,000 per year;

assuming ridership of 843 per night (based on existing counts), the net cost

would be $757,000, with a subsidy of $2.46 per rider, in line with existing bus

subsidies—the cost might be slightly higher if the T needed to assign an inspector to the overnight service and extra police personnel, but they may already be on duty at those hours and could be shifted from overnight layover facilities.

Further, if Massport provided the

link between Copley and the Airport on an in-kind basis (as they do for SL1

airport fares), it would reduce the cost to the MBTA by approximately 10%; if Massport

through-routed such services along the route of the 117 it would reduce the

MBTA’s expenditure by 20%. Thus the range of cost to the T would be somewhere

between $600,000 and $1.25 million, between 7% and 13% of the cost of the most

recent discontinued late-night service. This service would serve approximately

308,000 riders annually.

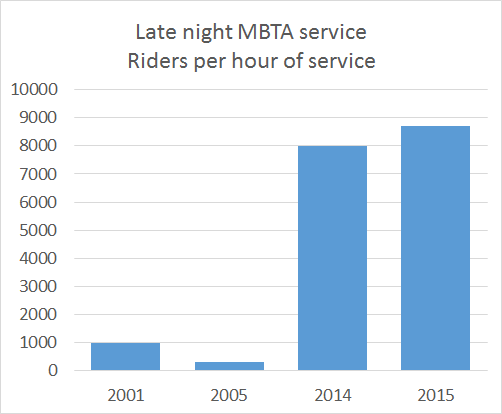

While “Night Owl” bus service was

run from 2001-2005, it was perceived as serving very different population and purpose than this

proposal, focusing on the “drunk college kid” demographic on Friday and

Saturday nights only (the most recent late night iteration had the same issue, although the T’s equity analysis showed otherwise). While that population would certainly benefit from

overnight service, this service would be aimed directly at providing better

access to overnight jobs—in addition to the airport, most routes would pass

nearby major hospital clusters—especially from low-income areas.

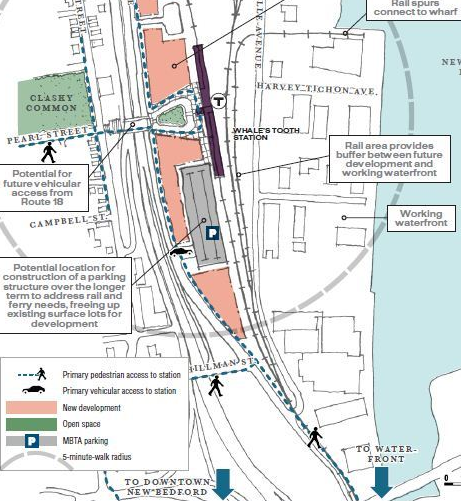

These routes would (unlike the

prior late night services) follow existing bus routes and stops, provide

coverage to much of the region’s core neighborhoods—but not necessarily to each rail station’s front door. For example, the Green Line in Brookline would be served

by the 57 bus along Commonwealth Ave and the 39 bus on Huntington Ave, within a

mile of the B, C and D branch stations in the town, thus providing a similar

level of service more efficiently (and obviating the need to create nighttime-only

bus stops along the rail lines). Most of the densely populated portions of

Boston, Brookline, Cambridge, Chelsea, Everett, Revere, Malden, Somerville and

Medford would be within a mile of service, with additional service to parts of

Newton and Watertown.

In addition, by following normal bus lines, buses

would use existing, known stops along major streets (rather than requiring

passengers to search for nighttime-only stops adjacent to or nearby rail

stations), and bus numbers could even match daytime routes (for instance routes

could be named: N15/9, N28/SL5, N32/39, N57, N1/88, N93/101, N117) to provide

continuity. The goal is to make the system both useful and easy to understand

both for regular users and customers with less-frequent overnight needs. (Using existing routes would also reduce the start-up costs for such a service.)

The T’s

current

plans to mitigate the removal of late-night service are anemic, targeting a

single line or a couple of trips on a single day. This proposal, on the other

hand, would bring overnight service to much of the area which hasn’t had such

service in more than 50 years. It would be a win-win solution. It would benefit

the Fiscal Management Control Board by focusing on low income areas and job

access routes while costing a small fraction of the recent late-night rail

service, and by showing that its goal was to provide better service, not just cut existing trips. But more importantly, it would benefit the traveling public, by

allowing passengers to make trips by transit to major job sites at all hours of

the day.

It would be important, as well, to run this plan with discrete goals in mind; while the late night service was painted as a failure by MassDOT, by comparing the ridership to the previous iteration of late night service, it was an

unmitigated success. The T’s mitigation plans would add buses piecemeal to its early morning system with no specific performance metrics. Instead, it should look in to creating a better network with specific goals, and measure the efficacy of the system in providing better connections to people traveling at odd hours.

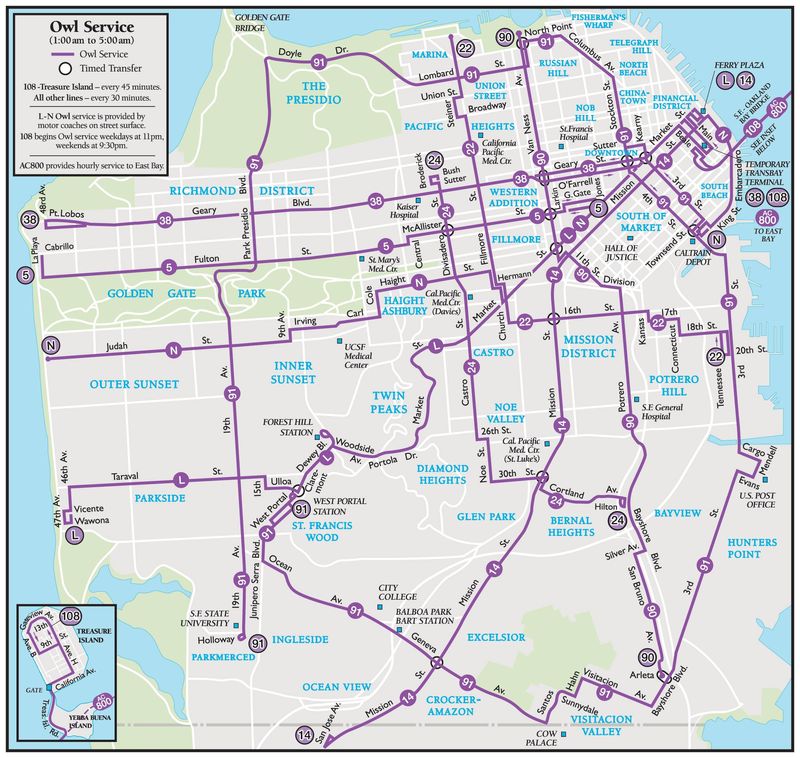

This plan is designed to be affordable and robust, serving

real needs across the region, responding to social and mobility equity, and

doing so without the need to turn to the private sector, which cannot and will

not offer similar service at such affordable costs. Should it work, it would

enable the MBTA to set a standard for quality 24/7 service—service which is

provided in Philadelphia, Seattle, Cleveland and Baltimore, not to mention peer cities like New York, Chicago and San Francisco—and the kind of

service a city and region like ours both needs and deserves.

*****

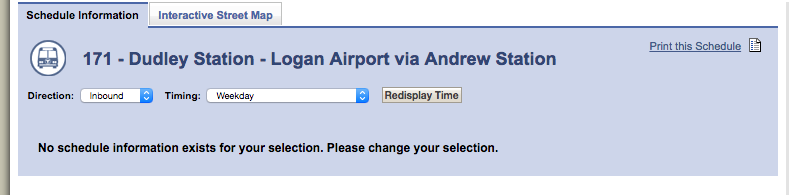

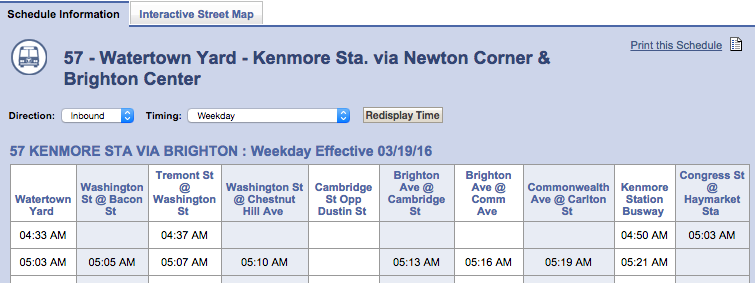

Here are sample schedules, assuming a :30-past-the-hour pulse at Copley. Schedules are based on current early-AM service. These times would be repeated hourly at 1 a.m., 2 a.m., 3 a.m. and 4 a.m. daily and 5 a.m. Sunday. Each route would require one vehicle unless otherwise noted.

Ashmont-Andrew-Copley (15 Bus, Red Line Ashmont Branch)

Dep Ashmont Station 1:02

Andrew Station 1:17

Arr Copley 1:28

Dep Copley 1:35

Andrew Station 1:46

Arr Ashmont Station 2:00

Mattapan-Dudley-Copley (28 Bus, Silver Line Washington)

Dep Mattapan Station 1:03

Dudley Square 1:14

Arr Copley 1:25

Dep Copley 1:35

Dudley Square 1:46

Arr Mattapan Station 1:57

Hyde Park-Roslindale-Forest Hills-Longwood-Copley (32 Bus, 34 Bus, 39 Bus, Orange Line, 2 vehicles)

Dep Hyde Park 12:50

Forest Hills 1:04

Longwood Medical Area 1:16

Arr Copley 1:25

Dep Copley 1:35

Longwood Medical Area 1:44

Forest Hills 1:56

Hyde Park 2:10

Watertown-Brighton-Kenmore-Copley (57 Bus, Green Line)

Dep Watertown Square 1:02

Kenmore 1:19

Arr Copley 1:25

Dep Copley 1:35

Kenmore 1:41

Arr Watertown Square 1:58

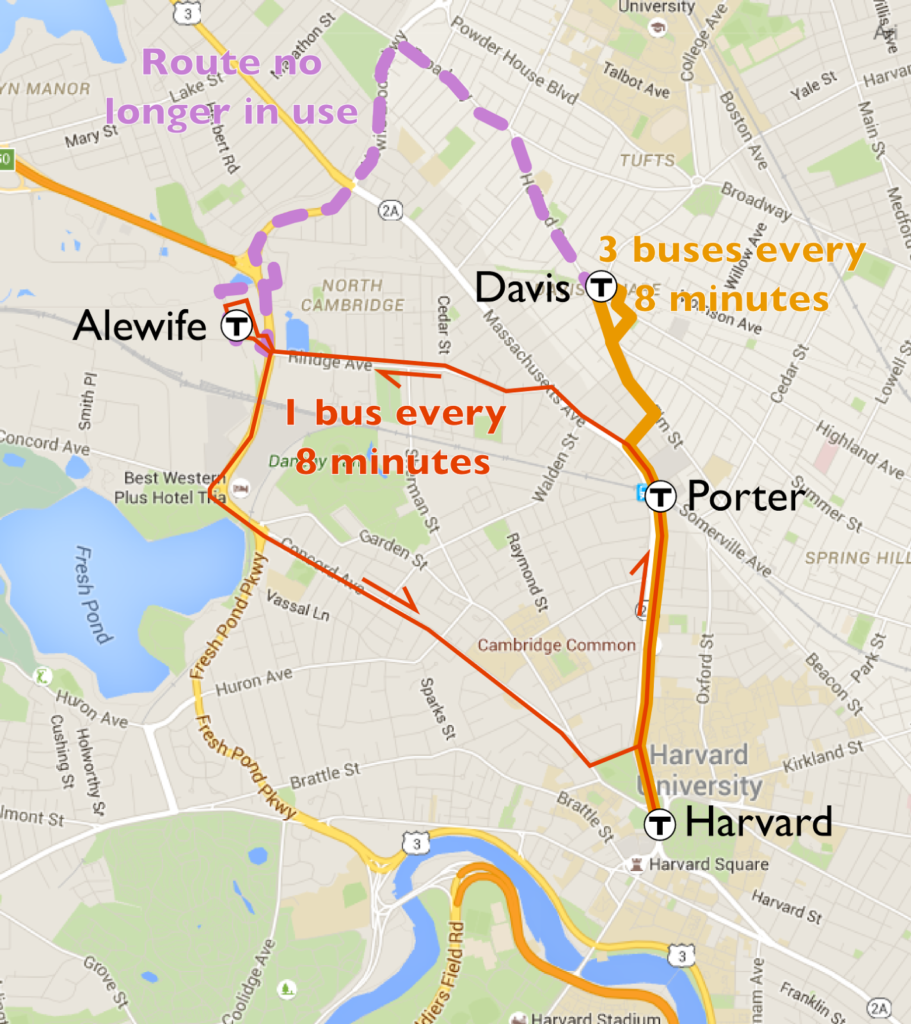

Clarendon Hill-Davis-Harvard-Copley (Red Line Alewife, 87/88/89 Bus, 1 Bus)

Dep Clarendon Hill 1:03

Davis 1:06

Harvard 1:12

Arr Copley 1:25

Dep Copley 1:35

Harvard 1:48

Davis 1:54

Arr Clarendon Hill 1:57

Malden-Medford-Sullivan Square-Haymarket-Copley (Orange Line North, 101 Bus, 93 Bus, 2 vehicles)

Dep Malden 12:49

Medford 12:59

Sullivan Square 1:07

Haymarket 1:17

Arr Copley 1:25

Dep Copley 1:35

Haymarket 1:43

Sullivan Square 1:53

Medford 2:01

Arr Malden 2:11

Broad & Ferry-Sullivan Square-Haymarket-Copley

Broad & Ferry 1:00

Sullivan Square 1:10

Haymarket 1:17 (express via Rutherford)

Arr Copley 1:25

Dep Copley 1:33

Haymarket 1:41

Sullivan Square 1:48 (express via Rutherford)

Arr Broad and Ferry 1:58

Wonderland-Chelsea-Airport (Blue Line, 111 bus, 117 bus)

Dep Wonderland 1:31

Chelsea 1:44

Arr Airport 1:55

Dep Airport 2:00

Chelsea 2:11

Arr Wonderland 2:26

Copley-South Station-Airport

Dep Copley 1:32

Arlington via Boylston 1:34

Washington via Boylston 1:35

South Station via Essex 1:38

Seaport 1:41

Terminal A 1:45

Terminal B 1:47

Terminal C 1:49

Terminal E 1:51

Arr Airport Station 1:55

Dep Airport Station 2:04

Terminal A 2:04

Terminal B 2:06

Terminal C 2:08

Terminal E 2:10

Seaport 2:14

South Station 2:18

Washington via Kneeland 2:21

St James via Charles 2:24

Arr Copley 2:27

Alternate Copley-Airport-Wonderland through service (2 vehicles; this would provide better connections downtown but may not serve airport shifts as well from Chelsea and Revere):

Dep Wonderland 12:38

Chelsea 12:53

Terminal A 1:06

Terminal E 1:12

South Station 1:19

Arr Copley 1:25

Dep Copley 1:35

South Station 1:41

Terminal A 1:48

Terminal E 1:54

Chelsea 2:07

Arr Wonderland 2:22