I spent a few days in Colorado for a wedding and (shocker) rode the transit system there quite a bit. Oh, I hiked and trail ran, too. I didn’t take a train trip, but did ride a variety of buses (including the spectacular N route up and down Boulder Canyon), but I did wander around Denver some, and was witness to the spectacular new Union Station project. It has a eight-track rail terminal (two pairs of three-track high-level platforms and two low-level platforms for long distance service) and a connected underground bus terminal which has access to nearby HOV lanes. And dozens of cranes erecting buildings around it.

|

The N bus goes up and down a 10% grade through

Boulder Canyon. It’s a beautiful ride, although it must

be one of the more difficult routes to drive. A friend said

that during a snowstorm drivers have asked passengers

to move to the back of the bus to increase traction. |

Most impressive? The rail terminal is fully electrified. When Denver’s Commuter Rail lines begin service next year, they’ll be operated fully under the wire, with the same electrification (25kV 50 Hz AC) that Amtrak runs between Boston and New Haven. And they are planning to operate high quality service: some of the most frequent Commuter Rail in the country, with 15 minute headways all day on some lines, and never worse than 30 minutes between trains. Only a few lines in the country (in the New York area) can boast that kind of frequency.

This is not the typical newly-built Commuter Rail built in the US. That would be what you get in Minneapolis, Nashville, Dallas or Seattle: moderately-frequent service at rush hour superimposed on a freight railroad and little service at other times. Legacy systems tend to do better, but the MBTA’s service leans towards the latter, especially outside of rush hours, when most lines have service gaps as long as 2 hours (or in some cases, longer).

|

| Denver’s Union Station terminal is particularly impressive. |

There’s one MBTA commuter line in particular which could use more frequency: the Fairmount Line. Unlike most of the Commuter Rail lines, it doesn’t stretch far in to the suburbs, passing through town centers, park-and-rides, and marshes and swamps. It has no four-plus mile gaps between stations, some of which are parking lots far from where anyone lives, with few riders off-peak. Instead, it serves a dense part of Boston with stations every mile, or in some cases, even more closely spaced. It should be run like a subway—like Denver is planning—yet it runs about as inefficiently as possible: service only operates once per hour, and that service is operated with a push-pull engine-and-coaches set-up which is suited far better to service Fitchburg, Middleboro or Rockport.

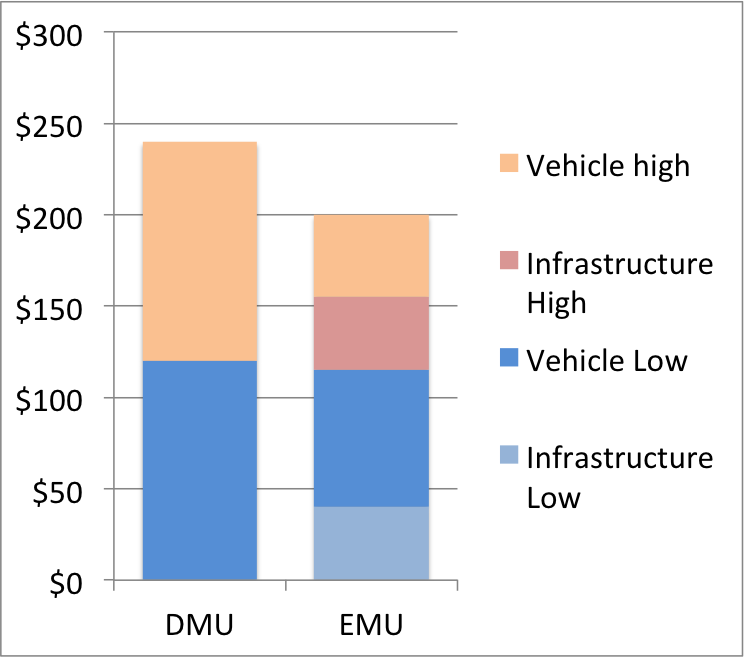

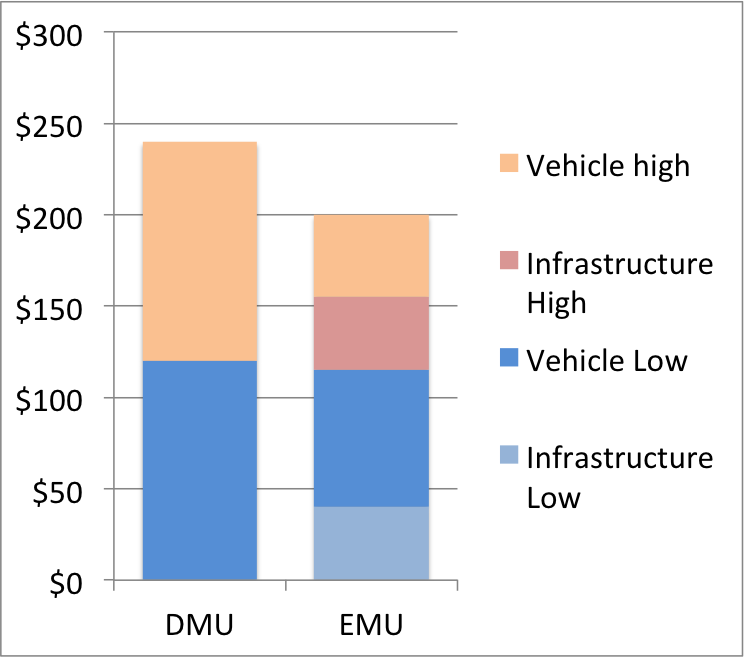

The T’s solution? It was to purchase diesel multiple units (DMUs) until the governor shelved that proposal (and quite possibly rightfully so). One potential reason? The projected cost for 30 of the vehicles was $240 million, or $8 million per car. DMUs are relatively unproven in the stringently regulated US railroad environment (although they have more success in Europe) and the cost for such vehicles would be very, very high. That leaves aside the fact that DMUs are best used for low-volume, longer-distance services. Anywhere which has frequent service and closely-spaced stations is better served by electric service (as Denver decided). Yes, the up-front, in-the-ground infrastructure costs more, but the operation costs are much lower, to say nothing of noise and local pollution reduction. And with off-the-shelf rolling stock (which is much cheaper) and an electrification system partially in place, it winds up being much less expensive overall.

The Fairmount Line is the perfect candidate for electrification. It is perhaps the most perfect candidate of any diesel line in the US outside of Chicago and San Francisco (where planning is in place to electrify Caltrain). It is only 9 miles long, and the final mile in to the terminal is already electrified (this would be by far the most expensive piece to run wire, but it’s already there). It has, in those nine miles, eight stops, meaning that the much faster acceleration afforded by electric propulsion pays dividends in travel time savings. It serves a corridor which could easily support trains every 15 minutes (especially if they were better integrated in to the rest of the system), with high population densities and accessible stations. Parallel subway and bus lines are over capacity, and it serves a poorly-served region which currently relies on slow-moving, crowded buses. And best of all, both ends of the line are adjacent to existing electrification—the northernmost mile is already under the wire!—so it would not need to be built as a stand-alone system, but would be integrated in to the existing electrification.

|

Even with initial infrastructure costs, it’s quite possible that

EMU service on the Fairmount Line would be no more

expensive than DMUs. The significant upside, however, in

procuring off-the-shelf technology,

is a lower chance of cost overruns. |

Then there are the costs. Electrifying existing rail is not very expensive: generally in the range of $5 to $10 million per mile (Caltrain’s costs, which are built to also allow high speed rail to operate, are $18 million per mile). Since this wouldn’t be built from scratch—since it can tie in to existing electrification—costs should be in the low part of this range. Let’s say it does cost $10 million per mile for the 8 as-yet unelectrified miles: that’s an initial cost of $80 million.

But then, instead of buying expensive, unproven DMUs, you can buy off-the-shelf electric multiple units, or EMUs. How off the shelf? Philadelphia and Denver both are running Silverliner V cars; in Denver’s case, on the same electrification system we have in Boston. On the basis of power and clearances, it is quite possible you could roll a Denver EMU in to South Station and run it up and down the Providence Line tomorrow (signal issues notwithstanding). Philadelphia placed an order for 120 cars for $274 million: a per-unit cost of $2.28 million. Even if Boston doesn’t get quite the same volume discount, 30 EMU units would, at $3 million each (the approximate cost of Denver’s units), cost $90 million. (2016 update: More-reliable M8s Connecticut just bought cost in the $4 million range, but include both third rail shoes and pantographs, which likely inflate cost somewhat.) Even with the initial investment in electrification, the total cost would be $170 million, 30% cheaper than that many DMUs! Even if a maintenance shop were needed (and Readville, adjacent to the end of the line, would be well situated for it), it would still come out cheaper. In the short term, heavy maintenance could be contracted out to MetroNorth’s New Haven shops, and cars towed down the line as need be. Even at $4 million—the average cost of DMUs produced today for other systems—the EMUs plus the wire would come out even.

An EMU is basically an oversized subway car: it’s built for faster speeds and is heavier since it is in the FRA’s domain, but otherwise has traction motors, a pantograph and a drivetrain. So it should cost about the same as (or a bit more than) a subway car, and indeed it does. The MBTA’s procurement of Red and Orange line cars comes in at about $2 million per car, so $3 million is in the ballpark. M8s or Silverliners cost more, since they are larger and faster vehicles, but not that much more, because rather than having to be designed for the specific specifications of Boston’s subway lines, they can be built to exactly the same specs as Denver or Philadelphia (although maybe we don’t want those) and shipped out the door.

|

|

An EMU can accelerate much more quickly, spend more time

at top speed, and save several minutes of operation time each trip.

|

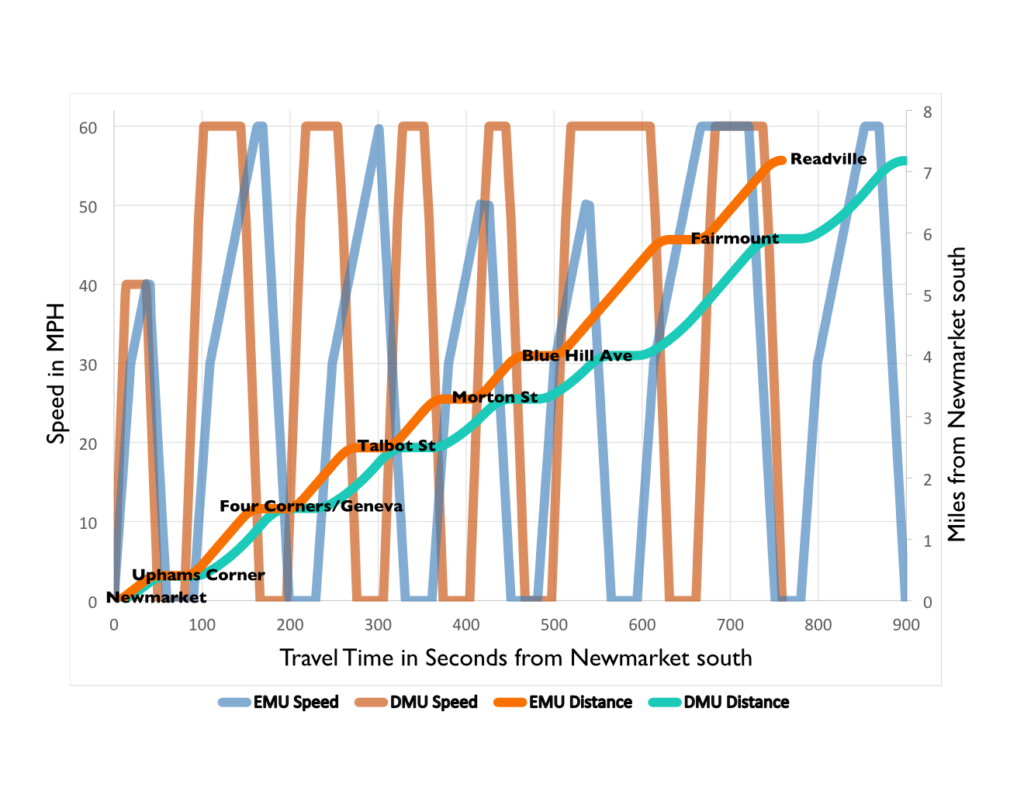

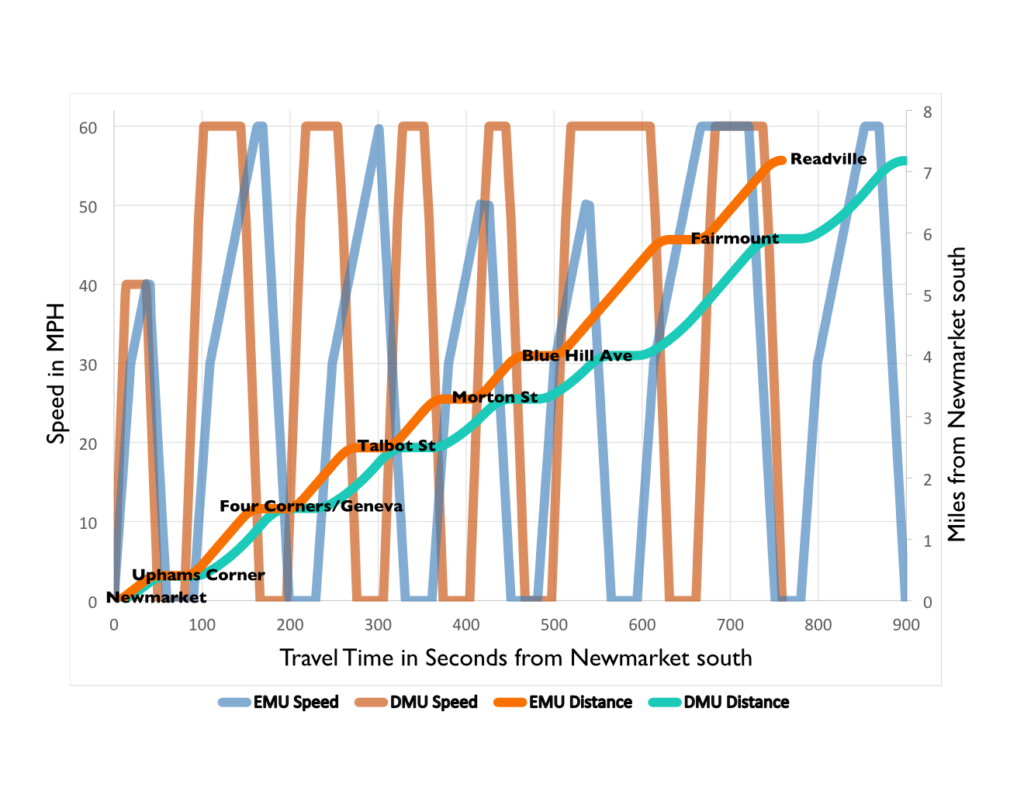

Then there are the benefits. First, electric trains are quieter. A lot quieter. Second, they don’t need to be kept running overnight to keep from freezing up. Third, they have far less local particulate pollution (and if renewables are used for power, they are much cleaner overall), important for the environmental justice communities the line serves. And finally, they accelerate faster. A lot faster. The rail cars being used in Sonoma and Marin counties are spec’ed for 1.6 miles per hour per second (mphps) to start, and just 0.7 mphps at 30 mph. (This is much like an MBTA diesel-hauled train.) The Silverliners? 3 mphps to 50 mph, and then declining to 2 mphps at 100 mph. In other words: to reach 30 mph, it takes a DMU 31 seconds; to reach 50 mph, it takes 1:15. A Silverliner can reach those same speeds in 13 and 24 seconds, respectively.

This means faster trip times, and operational savings. While a DMU train can cover the distance between Newmarket and Readville in 15 minutes, an EMU can cover that same distance in 12.5 minutes, even with the same top speed limit of 60 mph. With faster acceleration, the EMU spends a lot more time at that top speed, rather than chugging its way towards it (and with dynamic braking, it can also brake more quickly and efficiently). These time savings can either be put in to more frequent service, or more recovery time and fewer delays.

EMUs could also be used on the Providence Line, where the higher speeds—SEPTA’s Silverliners operate at 100 mph on the Northeast Corridor, the M8s have a similar top speed—would allow shorter, speedier and more reliable trips between Providence and Boston. Here’s a video of a Silverliner on the Northeast Corridor north of Philadelphia. It’s not accelerating at full bore, but still makes it to 50 mph within about 25 seconds and 80 mph within a minute (note the hard-to-see phone speedometer in the lower left). Thus in two minutes, from a dead stop, it covers 2.5 miles with an average speed of 75 mph. Electrified service on the Providence line would reduce run times by 25 to 33%—15 to 20 minutes—faster between Boston and Providence (depending on stopping patterns), dramatically reducing operating costs and allowing more service to run in the corridor, and attracting more passengers to boot.

In the longer run, it would start the T down the worthy path of electrification. In addition to Fairmount, 13 additional miles of wire would fully electrify the Stoughton and Needham lines, both of which use the already-electrified Northeast Corridor for part of their runs. Franklin would be a next best bet; a third of the 32 mile line already operates under the wire. Thus, for 42 miles of overhead—an investment in the range $200 to $400 million (plus another $50 to $100 for high level platforms)—the T could do away with inefficient diesel service on four of its commuter rail lines, which would serve as a springboard towards the future electrification of the rest of the system. The cost savings alone would likely tally to millions of dollars per year.

It is silly to run diesel service under a wire. While MARC, in Maryland, is moving away from electrics, it is really beyond explanation. Part of it may be that they are charged high rates for electricity by Amtrak, which owns the wire and track. The T, which owns the tracks, has a better negotiating position with Amtrak for electricity prices. But MARC is bucking the trend: most non-electric commuter railroads are moving towards overhead power. All-electric SEPTA is buying new electric motors as well as EMUs, Denver has started all-electric, Caltrain is moving towards electric operation, and Toronto is as well for its sprawling system.

Running Fairmount under a wire would make more sense than any of these systems. With DMUs delayed, the MBTA—which has long since had a distinct allergy to modern equipment in general and electrification in particular—needs to take a good, hard look at its cost and operational benefits of electric propulsion. It makes sense not only from an operational, pollution and environmental justice standpoint, but from a financial standpoint as well. Electric operation has long been anathema for the MBTA. But it makes operational and financial sense. It should be seriously considered.