Cambridge is in the process of starting a citywide master plan (right now it’s in the naming phase). The major thoroughfare in Cambridge is Massachusetts Avenue (Mass Ave for short, of course), and it is pretty much the only street in Cambridge that is more than two lanes each way. Except for a couple of locations, north of Harvard Square Mass Ave is 72 feet wide, and it could be a great street.

Unfortunately, it’s not. It’s basically a highway.

|

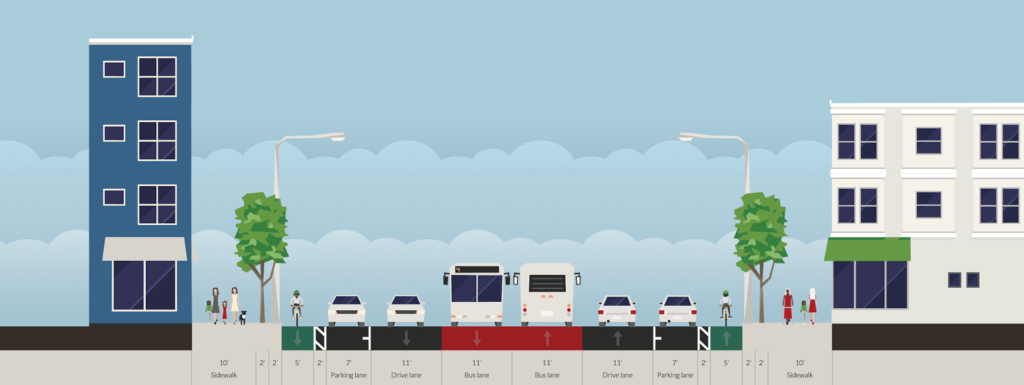

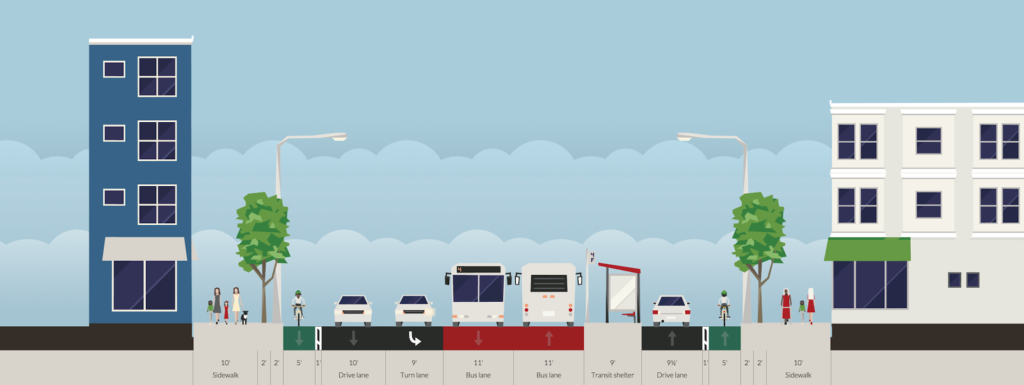

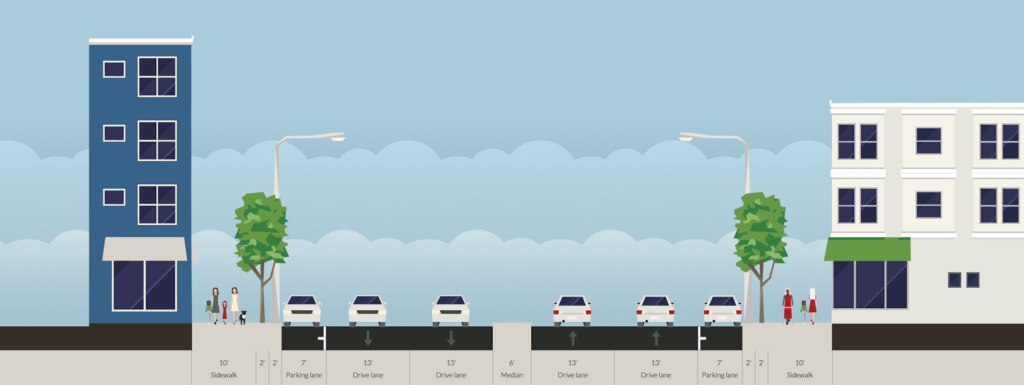

| Two wide lanes of traffic each way, parking and a median. Are we in Cambridge, or LA? All diagrams shown made in Streetmix, which is a fantastic tool for this sort of exercise. |

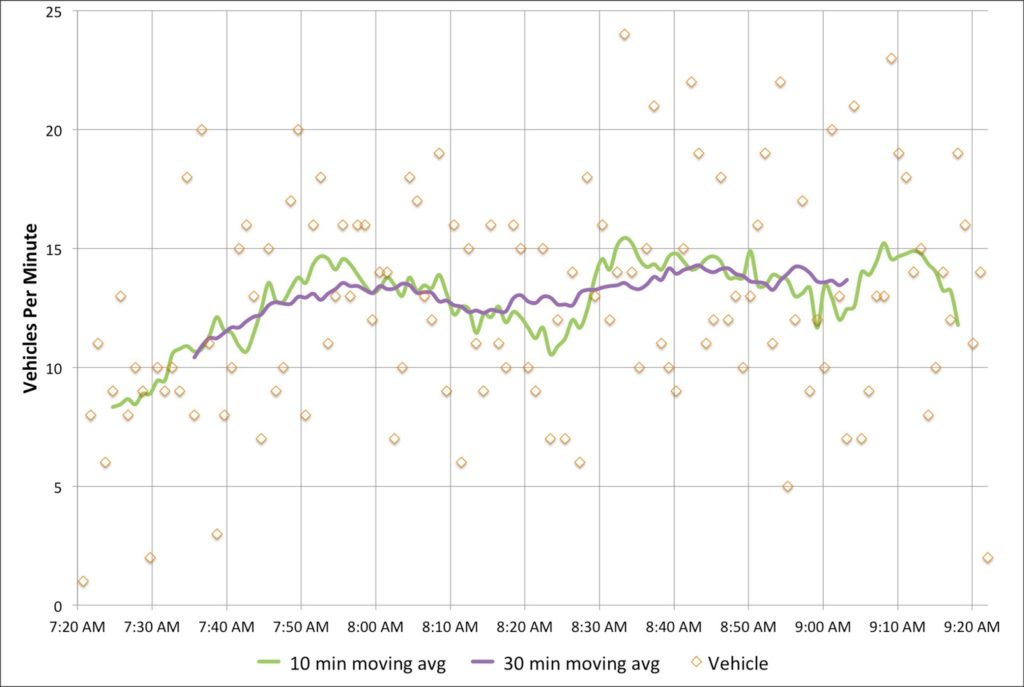

And that needs to change. The street currently serves two functions well: traffic and parking. There’s minimal traffic on Mass Ave because there is ample capacity (the bottlenecks are at either end of Cambridge). There is plenty of parking; nearly the entire stretch of the street has parking on both sides. And since the street is so wide, there is a median to help pedestrians cross, discourage left turns and make the traffic even faster. It is also a concrete waste of six perfectly usable feet.

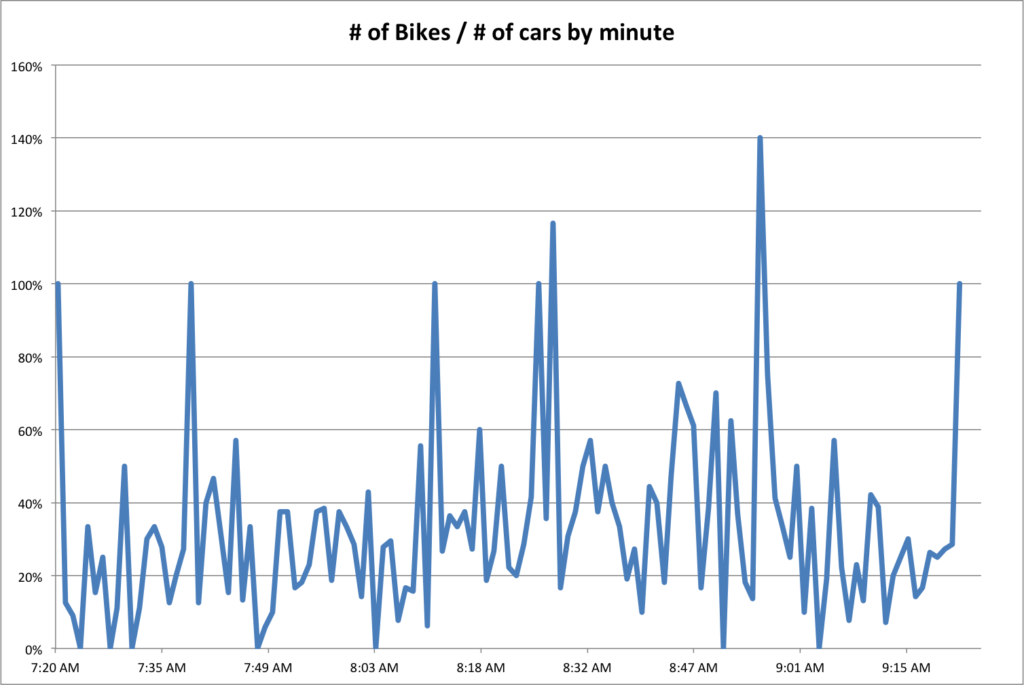

The street does have 14 feet of pedestrian facilities on either side, but these are hardly enough for the various uses there, which include bus stops, bike racks, sidewalk cafes, building access, power and light poles, etc. And the current lane width is ridiculous. Each side of the street is 33 feet wide: a 7 foot parking lane and two 13 foot travel lanes. Considering that Interstate travel lanes are only 12 feet wide, and 10 foot lanes are used throughout much of Cambridge, this is far, far more width than necessary, meaning that with the median there are 18 wasted feet of space on Mass Ave. Wider lanes cause drivers to speed, which endangers other street users. As for transit, the 77 bus limps along Mass Ave, stuck in traffic and pulling to the curb at every stop, only to wind up stopped at a light behind the cars that passed it.

We need to re-plan Mass Ave, and we need to rethink our priorities. In the 1950s, when the removal of transit safety zones in Mass Ave sped traffic and the end of the streetcars (at the City’s behest, no less), the main priority was vehicular traffic, with no mind paid to cyclists, little to buses, and not much to pedestrians. This is nearly completely backwards. How we should plan is:

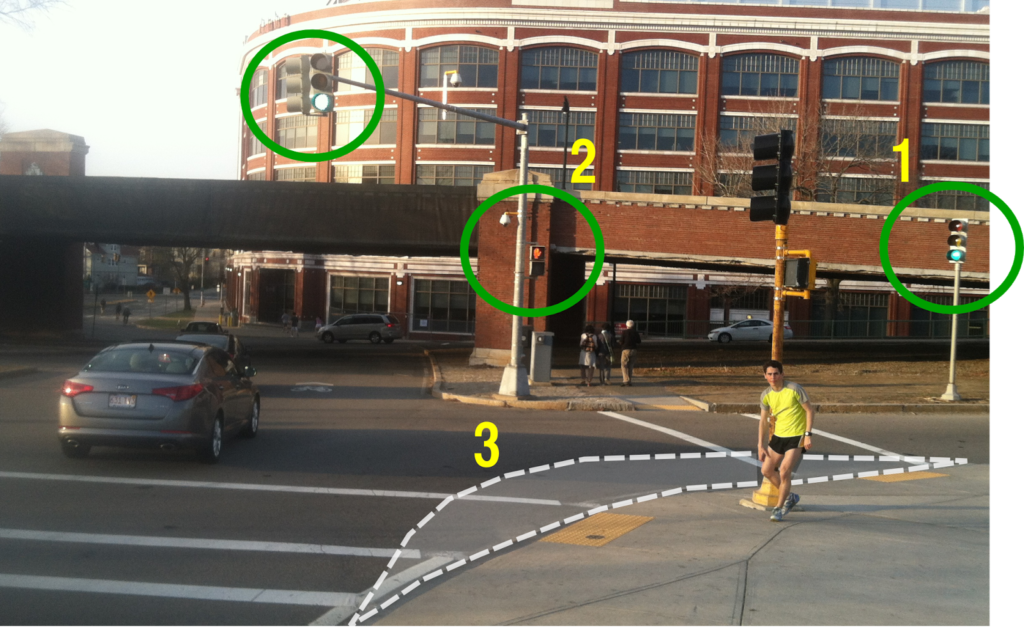

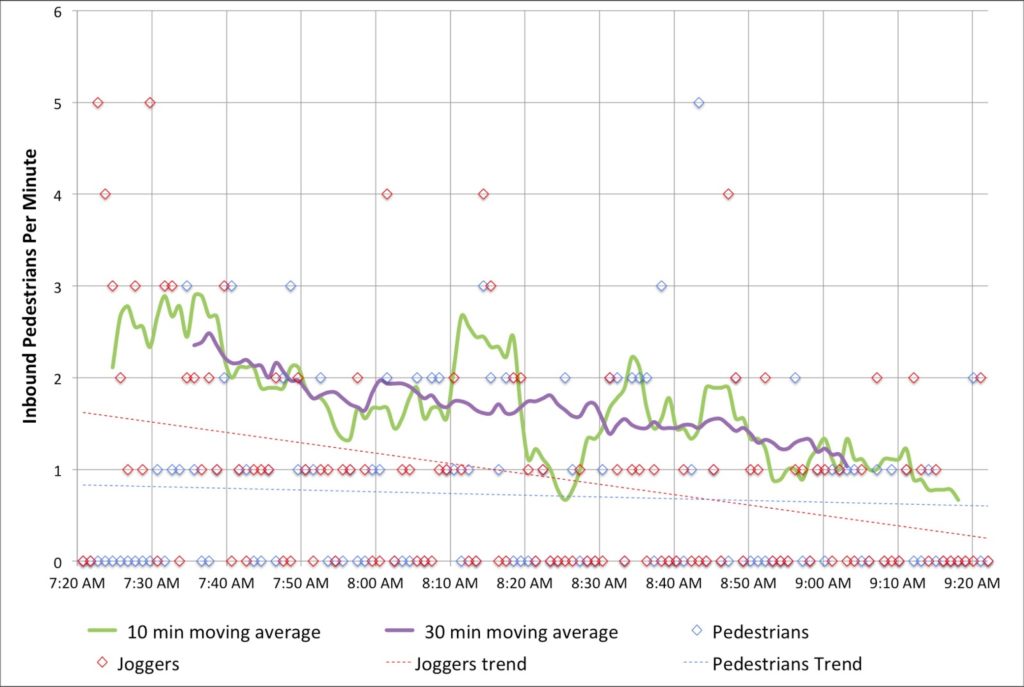

- Pedestrians. Every street user other than a pass-through driver is a pedestrian. We need to make sure crossings are manageable, sidewalks are wide enough, and traffic is slow enough to be safe.

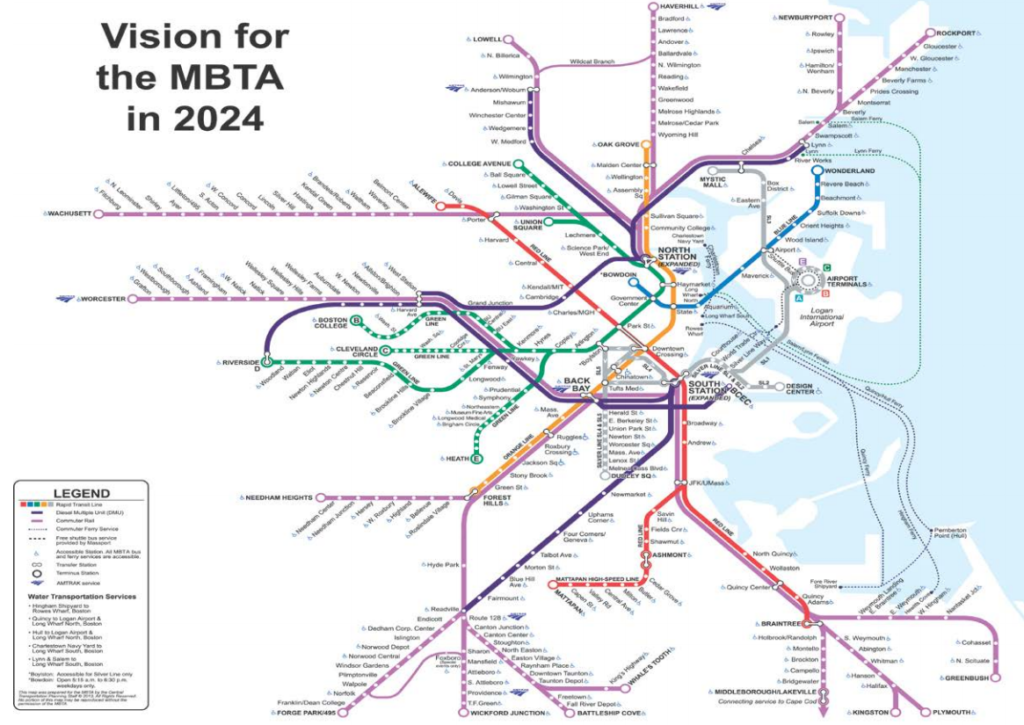

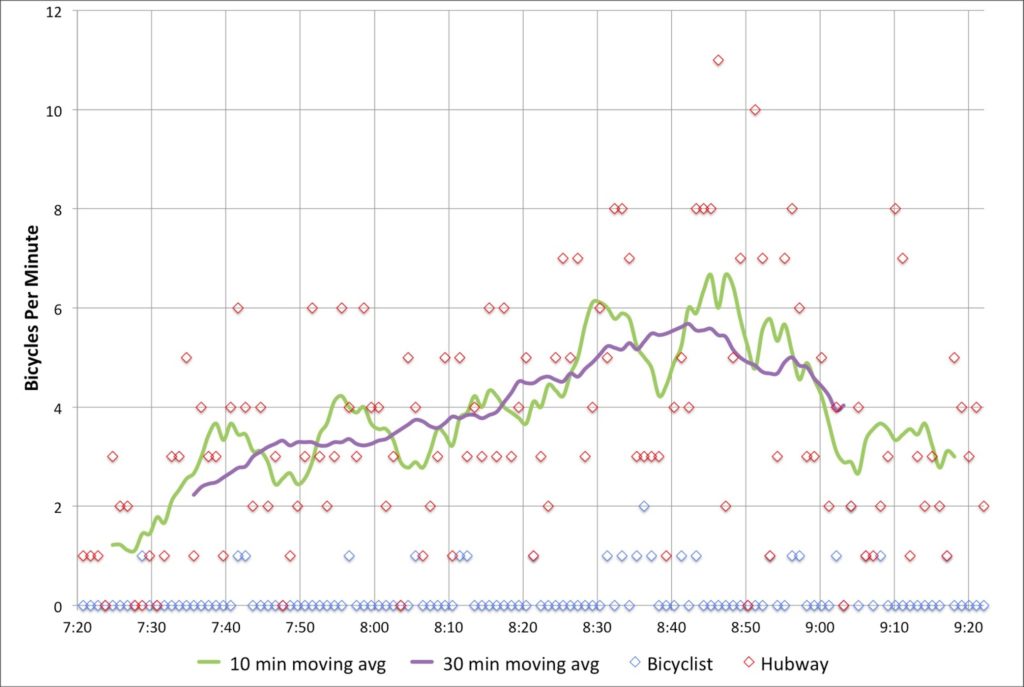

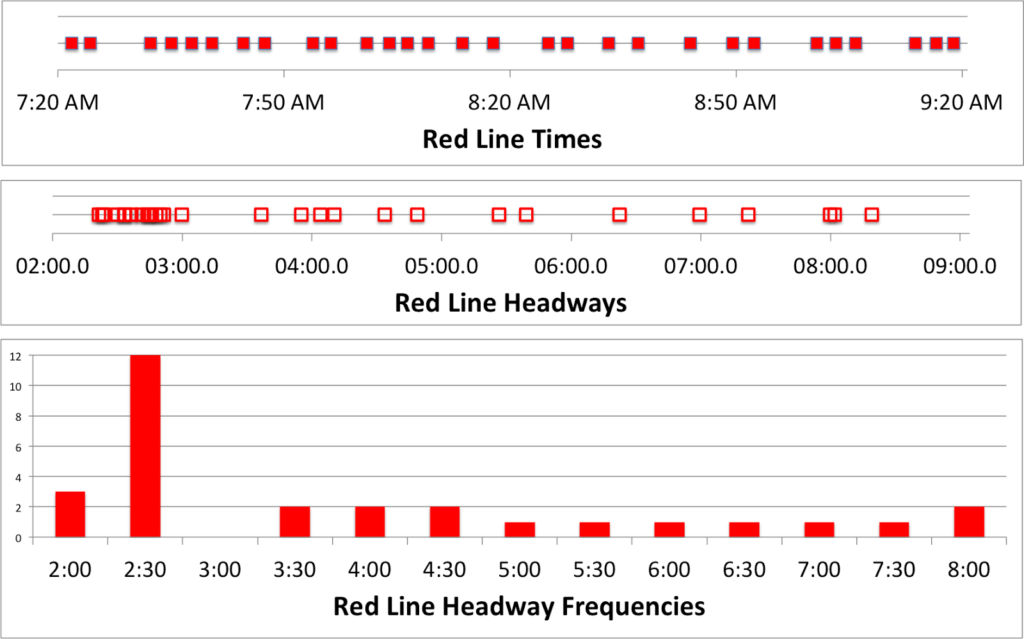

- Transit. Right now there are four bus lines along Mass Ave, the 77, 83, 94 and 96, carrying 13,000 passengers daily (as opposed to 20,000 vehicles). In addition, the street serves as the pull-out route for the 71 and 73 buses, serving 10,000 more. At rush hour, there may be a bus every two or three minutes.

- Cyclists. Safe cycling infrastructure is imperative for Mass Ave, as it is the straightest line between Arlington and North Cambridge and Harvard Square and points south and east. It is also the main commercial street for the neighborhood, and safe cycling facilities will allow residents to access businesses without driving. Rather than shunt cyclists to roundabout side streets, we should give them a safe option on Mass Ave.

- Cars. Yes, we need to provide for vehicles. We need a lane in each direction, enough parking to serve businesses (likely on both sides) and turn lanes in a few selected locations. Do we need two lanes in both directions? Certainly not; there are plenty of one-lane roadways which accommodate as much traffic as Mass Ave. And if we build a road that’s better for pedestrians, cyclists and transit users, many of the current drivers will travel by foot, bicycle or bus instead. We also need parking, and there’s enough for parking on each side. It would be eliminated where there are bus stops, but with fewer overall stops there would be only a minor loss of spaces. And with better non-driving amenities, fewer people would drive, anyway.

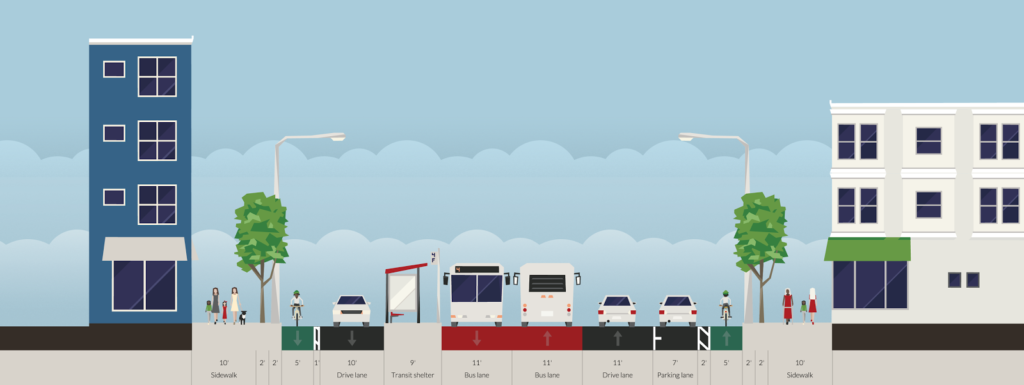

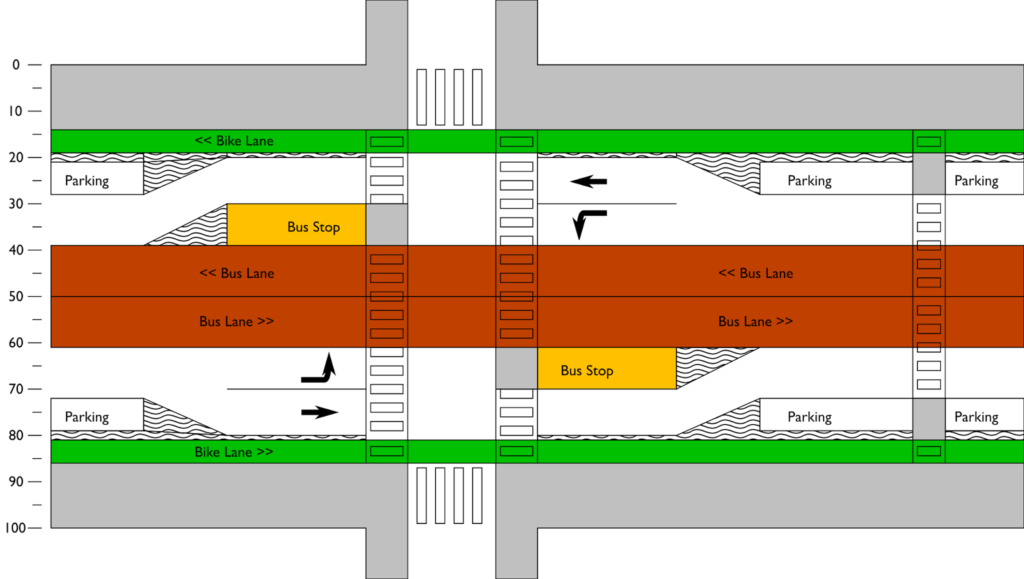

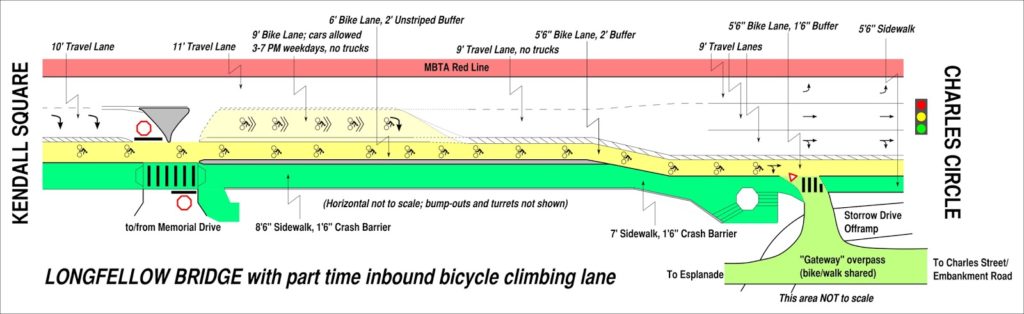

This is a typical section of street. The curbs and sidewalks are unchanged, but everything else is. Cars get one lane, plus parking. There are center bus lanes, which also allows cars to pass people parking, or a double-parked car, although this will require enforcement to keep drivers from using the bus lanes for travel or turns. Each lane is 11 feet wide, and emergency vehicles would also use the bus lanes to bypass traffic. On each side of the street, there is a 5 foot bike lane separated from parked cars by a 2 foot buffer (the bike lanes could either be at street or sidewalk level). This would be the baseline configuration of the street.

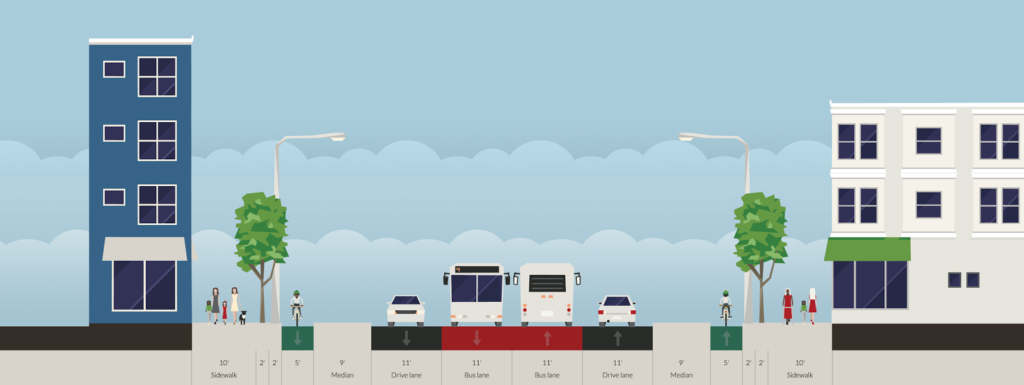

When a crossing of the roadway is desired away from a bus stop, the parking lanes would be replaced with curb bumpouts beyond the cycle track, meaning that pedestrians would only have to cross four lanes of traffic—44 feet—instead of the current 72. Crosswalk treatments would be included in the cycletrack to warn cyclists of the pedestrian crossing.

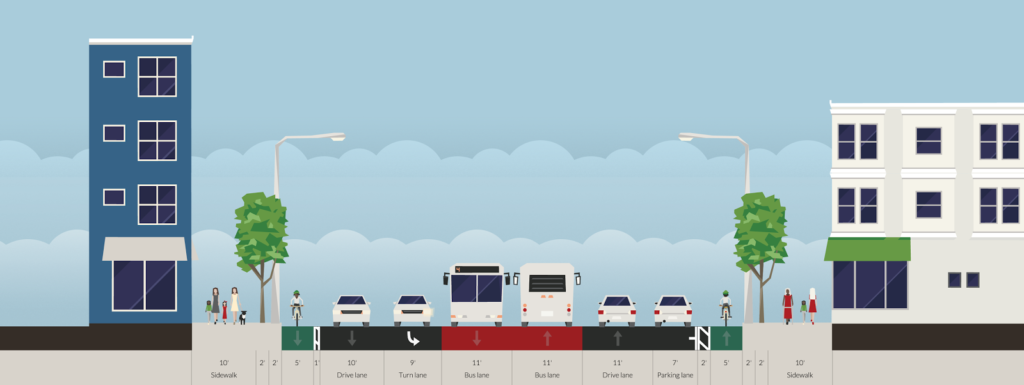

A turn lane could be accommodated by reducing parking in a manner similar to a bus stop. This would often be paired with a bus stop opposite the turn lane, with through traffic proceeding straight and the turn lane becoming the bus stop.

What would it look like from above? Something like this:

In the 1950s, we planned Mass Ave for cars. Cambridge can do better. In 2015, we were honored to have built what was described as the best new bicycling facility in the nation. It’s high time we remake Mass Ave, this time for everyone.