There’s an article on TheAtlanticCities which is bouncing around the office about how painful it is to wait for a train (I’d add: especially if you don’t know when it might come). But even with the proliferation of countdown timers (except, uh, on the Green Line), any disruption to the published (or, at least, idealized) headways can cause headaches. And when headways get at all discombobulated, passenger loading becomes very uneven, resulting in a few very crowded trains that you, the passenger, are more likely to wind up waiting for and squeezing aboard.

For instance, let’s say that you ride the Red Line in Boston. The published headway is 4.5 minutes (two lines, 9 minute headways for each line). Assuming you’re going south through Cambridge, the agency should be able to send out trains at the exact headways from the two-track terminus, barring any issues on the outbound run. You’d expect that, upon entering the station, you’d have an average wait of 2:15, and the longest you’d ever wait for a train would be 4:30 (if you walked in just as the doors were closing and the train was pulling out of the station).

In a perfect world, this would be the case. In the real world, it’s not. In fact, it probably seems to many commuters that their average wait for the train is more in the four-minute range, and sometimes as long as seven or eight minutes. And when a train takes eight minutes to come, the problem compounds as service bunches: the cars get too full, and dwell times increase as passengers attempt to board a sardine-can train and the operator tries to shut the doors.

Here’s the rub: even if most services run on a better-than-average headway, passengers are more likely to experience a longer wait. Here’s an extreme example. Imagine a half hour of service with five trips. With equal headways, one would arrive every six minutes, and the average wait time would be three minutes. Now, imagine that the first four services arrived every 2.5 minutes, and the final one arrived after 20 minutes. The average headway is still six minutes. However, the experienced average is far worse. Unless the services operate at that frequency due to load factors, passengers likely require the service at a constant (or near-constant rate). Imagine that one passenger shows up each minute. The first ten are whisked away quickly, waiting no longer than three minutes. The next 20 wait an average of 10 minutes, with some waiting as long as 20. In this case, even with the same average headway, 14 passengers—nearly half—wait longer than the longest headway if the service was evenly-spaced.

I used the Red Line as an example because I have experience with this phenomenon, and also data. Back when I first collected Longfellow Bridge data, I tracked, for two hours, how often the trains came. It turns out that the headway is actually 4:10 between 7:20 and 9:20, more frequent than advertised. However, nearly half of the trains come within three minutes, which means that there is a long tail of longer headways which pulls the average down. So instead of an average wait time of 2:05, the average user waits quite a bit longer.

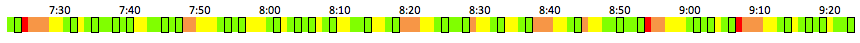

Assuming that each train carries all passengers from each station (not necessarily a valid assumption), the average customer waits 2:32. This doesn’t seem like a long time, but it means that while the trains are run on approximate four minute headways, the actual experience is that of five minutes, a loss of 20% of the quality of service. Five minute headways aren’t bad. The issue is that there are several periods where customers wait far longer than five minutes, resulting in overcrowding on certain trains, and longer waits for the same ones. The chart below shows wait times for each minute between 7:23 and 9:23. Green is a wait of 2:15 or less, yellow 4:30 or less (the advertised headway). Orange is up to 6:45, and red is longer. About one sixth of the time a train is running outside of the given headways. And three times, it is longer than 150% of the advertised headway.

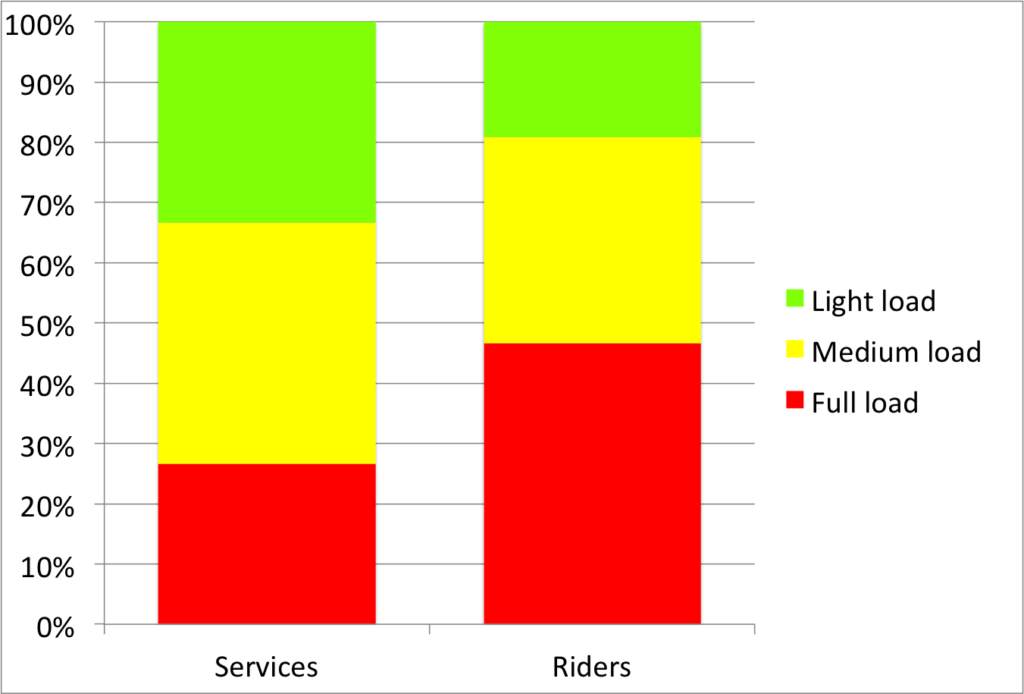

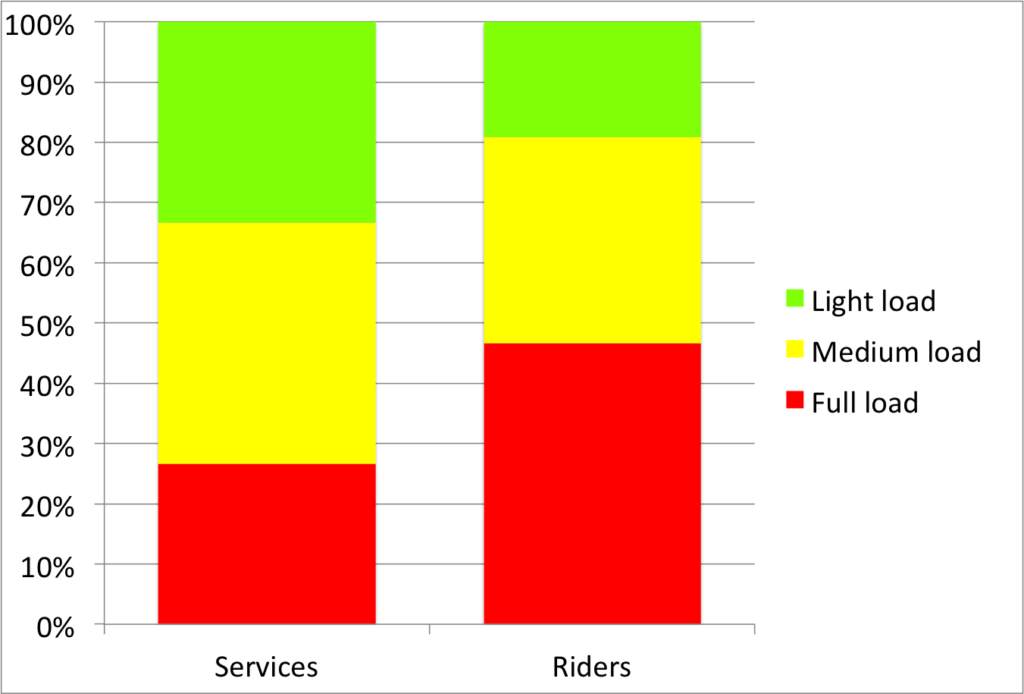

Another personal observation is that, try as I might, I seem to always get caught on a packed-full train. This is due to the same phenomenon. Of the 30 trains noted, only eight of them had headways of more than 4:30. Those 8 trains—which, assuming a constant flow of riders, accounted for 27% of the passengers—served 56 of the 120 observed minutes, carrying 47% of the ridership! Ten trains came within 2:30 of the previous trains. These trains accounted for 33% of the service, but only served 19% of the ridership. So while one-in-three trains is underloaded, you only have a one-in-five chance of getting on one of those trains. And while only about a quarter of services are packed full, you have a nearly 50% chance of riding one of those trains. So if you wonder why it always seems like your train is packed full, it’s because it is. But there are just enough empty services that once a week you might find yourself in the bliss of a (relatively) empty train car.

Another personal observation is that, try as I might, I seem to always get caught on a packed-full train. This is due to the same phenomenon. Of the 30 trains noted, only eight of them had headways of more than 4:30. Those 8 trains—which, assuming a constant flow of riders, accounted for 27% of the passengers—served 56 of the 120 observed minutes, carrying 47% of the ridership! Ten trains came within 2:30 of the previous trains. These trains accounted for 33% of the service, but only served 19% of the ridership. So while one-in-three trains is underloaded, you only have a one-in-five chance of getting on one of those trains. And while only about a quarter of services are packed full, you have a nearly 50% chance of riding one of those trains. So if you wonder why it always seems like your train is packed full, it’s because it is. But there are just enough empty services that once a week you might find yourself in the bliss of a (relatively) empty train car.

Overall, I mean this as an observation of headways, not as an indictment of the MBTA. Running a railroad with uneven loads (especially at bus- and commuter rail-transfer stations), passengers holding doors and the like can quickly cascade in to a situation where certain trains are overloaded, and others pass by with plenty of room. Still, it’s infuriating to wait. But it’s interesting to have data, and to visualize what it looks like during the course of what seems to be a normal rush hour.

(On the other hand, there are some services, like the 70 bus, which have scheduled uneven headways and where the actual level of service is significantly impacted, but that’s the subject of another post entirely.)