|

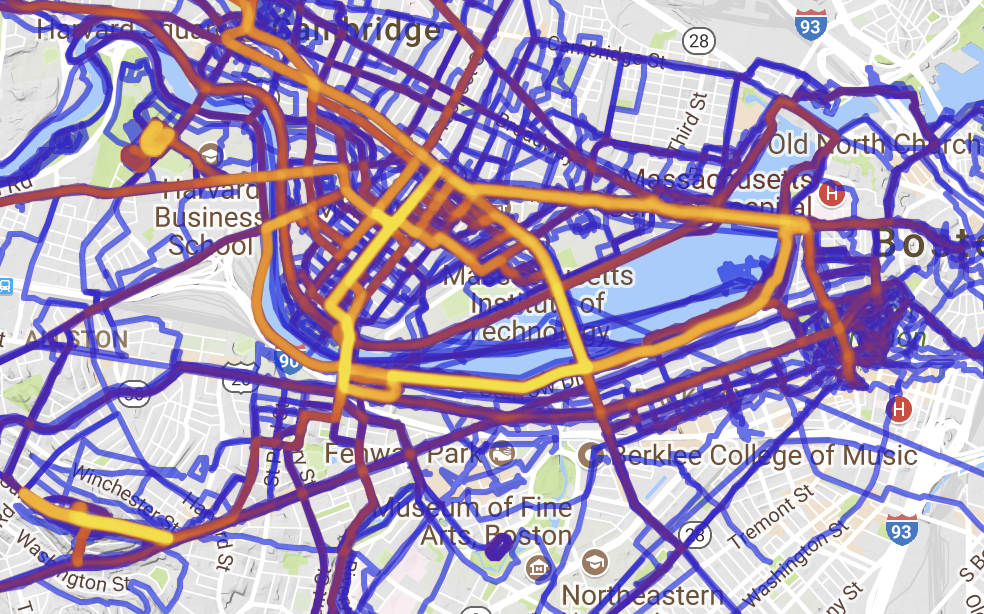

| Personal Strava heat map via here. |

While it may not be news to many regular readers, in addition to riding bikes and transit advocacy, I dabble in running. Living in Cambridge, one of my regular routes is along the Charles River. According to Strava, I’ve run the section between the BU footbridge and the Harvard Bridge 132 times although this is certainly an under-count due to both GPS issues as well as times when I didn’t run Strava (contrary to public belief, if it isn’t on Strava it is still possible that it did happen). Long story, short: I run along Storrow Drive a lot.

And I’ve noticed something as I navigate the narrow section of path above the buried Muddy River: the lane allocation westbound in the area of the Bowker Overpass is not optimal. As a narrative, proceeding west from Mass Ave:

- 3 lanes passing under the Harvard Bridge

- These split in to two 2-lane “barrels”, one feeds Kenmore/Fenway, immediately splitting in to two lanes on to the Bowker Overpass and one to Beacon St, the other feeds two lanes west along Storrow Drive.

- This second barrel is then met by the flyover from the Bowker Overpass, which is, in turn, fed by two lanes from the Bowker and one lane from Beacon St.

- This ramp merges down to one lane, and then merges in to the Storrow Drive mainline, with a very short merge area (the signs, in fact, say “no merge area”) with poor sight lines as the merge is on the concave inside of a curve.

|

| No Merge Area = No good. |

It is this last section which is worst. If you attempt to enter Storrow Drive from Beacon Street, you have to merge in to:

- the two-lane Bowker ramp

- then merge from two lanes to one on the Bowker Ramp and

- then merge on to Storrow Drive

all within a span of 900 feet. The final merge is on to Storrow Drive with poor sight lines, high traffic speed, and no merge area. None of this is good. If these ramps were rationalized, however, these three merges could be replaced by a single merge, including the worst bottleneck at the entrance from Charlesgate to Storrow Drive, going from a dangerous merge to a continuous stream of travel. The state did this circa 2009 (you can see it on HistoricAerials here) but apparently didn’t change enough of the signage, which caused confusion further back, and some people complained, and rather than trying to make it work, they gave up. Old habits die hard. But we should make an effort to change them, rather than revert back to dangerous, inefficient roadways. The road was restriped to its current condition in 2011. There’s no word from the Universal Hubbian masses that it got appreciably better then: people probably got used to it, but it was too late.

This time, let’s not give up. Let’s get some data. Mine is anecdotal and circumstantial: anecdotal because when I observe the area there always seem to be more drivers exiting Storrow Drive to Charlesgate than continuing west and circumstantial because proceeding west on Storrow, the next exit point is at River Street, so there is relatively little reason to get on Storrow rather than to take the Turnpike (except, perhaps, to avoid a toll). So rather than splitting in to four, the three lanes under the Harvard Bridge could feed in to three separate lanes going to Fenway via Charlesgate, Beacon St and west on Storrow. The ramp from Charlesgate would then maintain a single lane on to the overpass, which would eliminate a further merge. So we need these data.

Now, here’s some real data. In the morning peak hour, 3400 vehicles per hour approach the ramp to Charlesgate. 2100 take the ramp, 1300 stay on Storrow, and 800 enter Storrow from Charlesgate. In the evening, 2000 take the ramp, and 2250 stay on Storrow, then joined by 1300 from Charlesgate. So the pinchpoint may be whether a single lane is able to handle 2250 vehicles; a quick spot count on a Thursday night in December showed about 2000 vehicles per hour during this peak time. This may well be a tight fit. But there are certainly single-lane ramps that handle more traffic (the ramp from 95 north to 128 north, for example). By observing the traffic flow, it is apparent that when Charlesgate backs up (not infrequent on normal days, to say nothing of evenings with Red Sox games), the left two lanes become de facto off-ramp lanes, with only the right lane open for through traffic. Codifying this would make the system safer and more efficient.

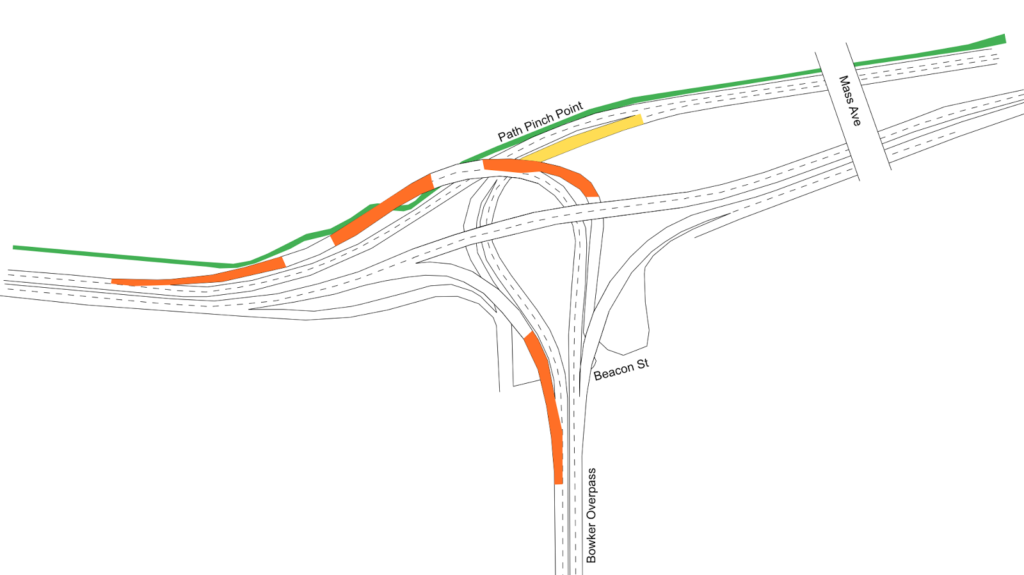

Here is the layout of the current ramps at Charlesgate, with orange areas showing the current merges, and yellow areas showing “sorting” areas where drivers have to choose the required lane. The proposal would simplify this, since each lane would lead to a specific destination, and signage could be improved. (This sign not only doesn’t accurately represent reality—the two right lanes both lead to Newton and Arlington—but it’s far too late for an errant driver to safely correct course. The next sign back has the same images, but slightly different, if somewhat more correct, information. Let’s ignore for a moment the tiny, white-on-blue destination sign no one could reasonably expect to read at 40 mph. If changed, the signs on the Harvard Bridge could read

Fenway Kenmore Sq Newton/Arlington

above each lane.)

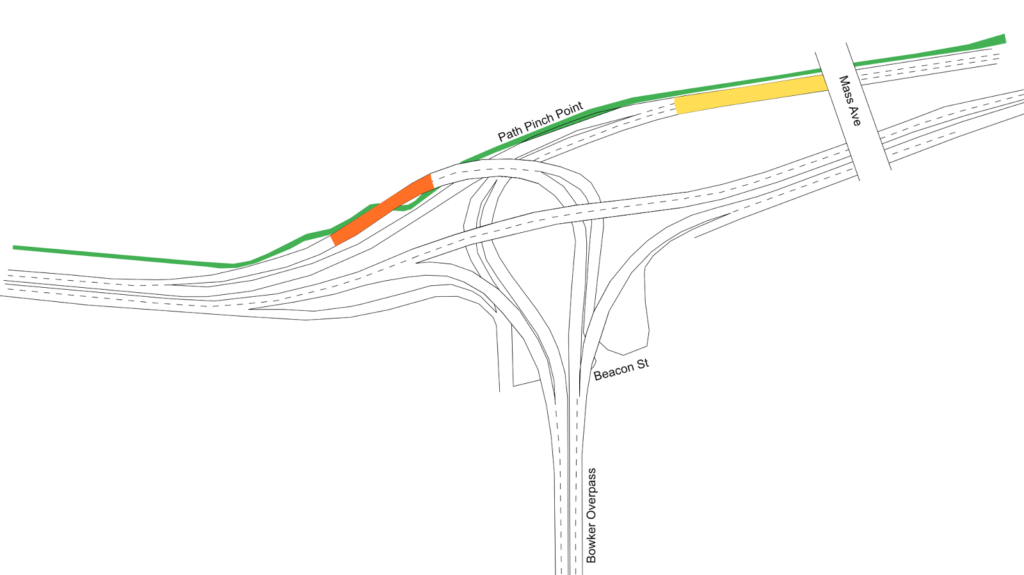

Here is the proposal:

Note that three of the four major merges in Storrow-Charlesgate complex disappear. Just by repainting lines on the road (and likely some physical chicanes to keep Boston Drivers from creating two lanes where they shouldn’t) we can decrease the number of merges by 75%. The one merge left occurs on the longest, straightest portion of the entire complex, and on low-speed ramps, with about 500 feet to merge: three times longer than the merge area when the ramp enters Storrow Drive. And other than signage and paint, there would be no infrastructure costs associated with this sort of project.

Why would a transit-bike advocate like me care about cars? Two reasons. First of all, system efficiency. This is a clear example of where some minor changes could be implemented to create a safer system with less friction, less idling, and less pollution. But the second is that this could be used to improve conditions for bicyclists and pedestrians. Why? Because maintaining the two lanes of Storrow Drive require a pinch point on the Paul Dudley White Path where it narrows from a width of 10 to 12 feet down to 8. If this portion of Storrow were narrowed to a single lane, it would provide plenty of room to widen the bike path and provide a better experience here for cyclists and pedestrians.

Should this be the end state of these ramps? Certainly not. Once the Longfellow is completed, the accident-waiting-to-happen ramp from Storrow to Mass Ave will be rendered redundant and should be closed to eliminate the crossing of the busy sidewalk and bike lane there. In the medium term, Peter Furth makes a strong case that surface roadways could probably handle the traffic, which would be cheaper to build and maintain (the current bridge structures date to the 1960s and are functionally obsolete). In the long run, Storrow Drive and the Charlesgate complex act as mainly as a last-mile distributor from the suburbs to urban job centers. The roads are “necessary” because we don’t have a functional transit system to allow easy travel between the north and south sides of the city (especially between the northern portion of Boston and the Longwood Medical Area complex). With a regional rail connection coupled with congestion-based road pricing (other than political obstinacy, there’s little to keep the DCR from erecting EZ-Pass gantries and tolling the roadway, and the DCR could certainly use the money) we could return the riverbanks to something closer to James and Helen Storrow’s vision. It’s not much, but improving these lanes, at least, would be a start.