This topic was raised by an IM discussion I was having with my dad as he sat on the tarmac on a plane in Saint Louis:

Dad: My flight has now been delayed a total of 2:35 on account of, they say, air traffic control in Boston because of weather.

Me: Hey question: if you could take a 6 hour train ride from Saint Louis to Boston (feasible, albeit barely) would you rather do that than deal with these airplane shenanigans?

Dad: You betcha. There ought to be a 90-minute hop from here to Chi, and then the eastbound super-express. What route would you propose for that?

Ask and you shall receive.

Before going in to the route (in a separate post to come later), it would be interesting to see what has been proposed for high speed rail routes, and what the genesis of such proposals has been. There have been several, and it is actually quite interesting how they have evolved. What I am going to try to illustrate here is that high speed rail has too-often been touted as a regional solution; it is really an interregional solution as well. Thus, I am consistently flummoxed that few maps show an interest in an East Coast-to-Chicago trunk line, paralleling one of the most congested and delay-prone air routes in the world. (Mention O’Hare and JFK, Newark or LaGuardia in the same breath and seasoned travelers will curse or faint.)

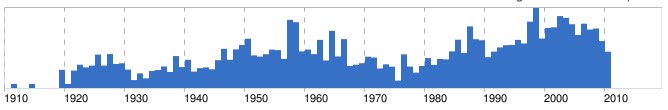

So, now to the maps. I’ve tried to link them in as best I can, but my apologies if some of the links break: some of these maps are rather old. We’ll start way back in the year 2000, when the Bureau of Transportation Statistics published an early draft of an HSR network. It should be noted that this was eons ago in the life cycle of high speed rail. Gas was cheap, airlines were profitable (ha!), and the Acela hadn’t yet run from Boston to Washington.

In general, this looks pretty similar to some of the more recent maps. So it’s pretty much a base. Which is problematic: once people have drawn lines on maps, it’s often hard to redraw them, no matter how little sense they make. Luckily, as a base, most of the nonsense here comes from connections not made, like not linking networks in Jacksonville and Tampa, Houston and Austin or DFW, and Cleveland and Pittsburgh. It’s the last of these which, as we’ll see, is somewhat persistent.

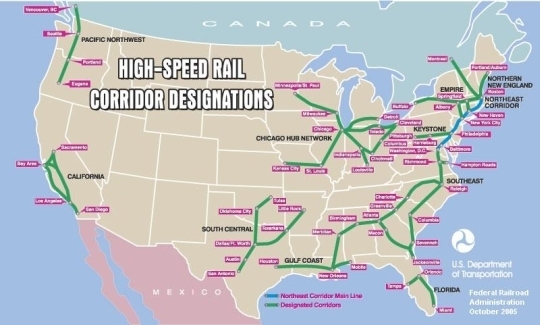

High speed rail didn’t come up much during the Bush Administration (which was preoccupied with throwing enough money to build these entire systems show here at the Iraq money pit), but a new map (from the DOT) was offered up in 2005, which was a general template for the next several years. And it was … pretty similar to the previous one.

It was being used by several sources as late as this year. In other words, from 2000 to 2009 there were basically no changes made.

Finally, the Obama administration, which has now promised money to high speed rail, released their own map, and, well, didn’t rock too many boats. Their “Vision for High Speed Rail in America” is not much more than a couple of tweaks of the existing map. And still, ten years later, regions are, for some reason, not linked.

In the mean time, there have been several regional agencies which have come up with their own maps. The two most prominent are in the Midwest and California. California’s map is relatively simple (although minor changes, such as which pass to use to get from the Bay Area to the Central Valley, have been the cause of much contention) and very nifty on their website. The Midwest map, which is less further along, has seen a bit more flux.

The first map released by the Midwest High Speed Rail authority was rather modest, vague and, frankly, not really high speed rail (with top speeds of 110 mph):

That map disappeared from their server earlier this year (the Web Archive grabbed it, however) and a new, more ambitious one arrived, along with the news that they’d push for 220 mph service from Chicago to Saint Louis (ooh, good idea):

This is actually one of the better maps I’ve seen. It might be overly ambitious, but it does show the high speed routes to major cities, with connections to the east coast, which have been missing previously. Of course, there is no straight line across the Midwest from Pittsburgh, but at least the network realizes that it should be interregional.

Finally, there are a bunch of maps created by various blogs and lobbying groups for high speed rail networks.

The Transport Politic blog offers:

Richard Florida talks about Megaregions and high speed rail without putting up a specific map (a good idea, perhaps)

But others take that map and run with it.

Finally, with that map as a base, a lobbying group called the United States High Speed Rail Association has an ambitious, 17,000 mile network.

So what’s the takeaway? Well, the first is that nothing is really set in stone (except, perhaps, in California). But the second is that only more recently has anyone started looking beyond the corridors first set forth in 2000 (and, presumably, even before then). Which is good. Because even the newest maps, none of which have the backing of the government, have some issues with linking together longer corridors. Both the USHSR’s map and the one from the Transport Politic go through Philly, Harrisburg, Pittsburgh, Cleveland and Toledo on their way from New York to Chicago, adding enough mileage to negate the use of the corridor for longer distances.

Update: America 2050 has posted a study that actually has some basis to it, and the map they create is probably the most sensible yet. . The Transport Politic thinks so, too.

. The Transport Politic thinks so, too.

In any case, these maps should be refined: a strong case could be made for the competitiveness of a high-speed line from New York (with branches to Philadelphia, D.C. and even Boston) to Chicago (with branches to Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Detroit, Columbus and other cities). Considering the dismal state of air service between the first and third largest cities in the country, and the horrors of getting from the CBD of each (the two largest downtowns in the nation) to the airports, a modern, 200 mph line could definitely hold its own.

A future post will discuss this.