A recent study (PDF) from a group called America 2050 has put together one of the most data-heavy (and that’s a good thing) approaches to examining high speed rail corridors in the country. There are still some issues, most notably the fact that corridors over 500 miles were ignored (yes, they should be weighted less than 200-400 mile corridors, but, no, with proper speeds attained, they shouldn’t be dropped) and their map does not seem to fully mesh with their data. Still, they take in to account such factors as transit accessibility in cities analyzed, economic productivity (higher local GDP is better), traffic and air congestion and whether the city is in a megaregion (this seems to be a rather ancillary data point).

Their subsequent phasing map, while better than most, seems to be, well, not completely in-line with their data. This is mainly because each corridor seems to be analyzed separately, and overlapping corridors, from their report, are not shown well.

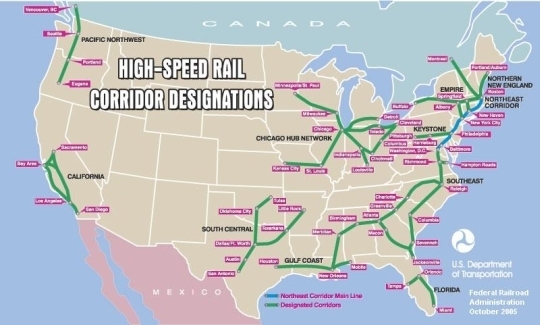

First, they did get the two big corridors right (the “no-brainers,” if you will): California and the Northeast Corridor. Both of these corridors have multiple city pairs in the top-10 of their analysis; in California the San Francisco-San Jose-Los Angeles-San Diego line and in the northeast the Boston-New York-Philadelphia-Baltimore-Washington corridor. Of course, those are obviously the top high speed rail corridors in the country. However, the rest of their “first phase” corridors are less obvious.

In an effort to, perhaps, not leave out the Midwest (where much of the current political support for high speed rail originates), they include, in phase 1, lines from a Chicago hub to Minneapolis, Saint Louis and Detroit. These are all worthy corridors but, according to their analysis, are not in the same echelon as the coastal corridors. Chicago to Saint Louis clocks in at 14th, trailing Chicago to Columbus by a spot. Chicago to Minneapolis ranks 25th, behind corridors such as Cleveland to Washington and Phoenix to San Diego.

With Chicago to Detroit (11th), however, things get interesting. Let’s introduce two maps in to the equation. The first is a map of the top 50 corridors analyzed by America 2050, with the color of a line indicating if they were in the top 50 (red), 40 (orange), 30 (green), 20 (light blue) or 10 (dark blue). Opacity is set rather low, so overlapping lines should show up considerably darker (see the Northeast Corridor, where four top-ten corridors intersect from New York to Philly). From Chicago to Minneapolis and Saint Louis, there are single lines. Despite the presence of some smaller cities (Decatur, Springfield, Urbana-Champaign; Milwaukee, Madison, Rochester) none of these corridors crack the top 50. (Milwaukee-Chicago was not calculated as it is less than 100 miles.) East of Chicago, however, there is a web of lines. From Chicago going east, three cities make the top 16: Detroit, Cleveland and Columbus. And east of there, these cities are all linked eastwards. (Any city with at least two corridors is shown with a point, its size corresponding to the number of corridors.)

So it begs the question: which routes are most applicable to high speed rail if we overlap corridors which could share significant trackage. For instance, Chicago to Detroit, Cleveland and Columbus could all share one high speed link, with short spurs to each of the cities. These three cities could all share a link across Pennsylvania (with Pittsburgh) to Washington, Philadelphia and New York. 11 of the top 50 city pairs are between New York, Philadelphia and Washington in the east and Columbus, Cleveland and Detroit in the west. Since most of the capital costs of constructing a high speed rail line is the initial capital cost, combining several corridors could dramatically reduce the amount of line needed, saving billions.

So, the second map. For this map, lines with little or no overlap were ignored. Other corridors were assigned a (rather arbitrary) point value based on their ranking:

1-10: 6 points

11-20: 4 points

21-30: 3 points

31-40: 2 points

41-50: 1 point

(Why did the top 10 get a slightly higher weight than the rest? Well, the numerical rankings of the top 10 ranged from 100 to 91. The rankings of the next 40 ranged from 91 to 85.)

Here’s another scheme: assign a route with a score of 85 one point, and an additional point for each increase in the score. This is, perhaps, a more equitable approach for larger corridors, and it really pops out the Northeast Corridor. A possible network of 2450 miles (1870 in the East and Midwest, 580 in California) could serve Boston, New York, Philly, DC, Pittsburgh, Columbus, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, San Diego, LA, San Jose and San Francisco (and several smaller cities, like Toledo, Harrisburg and Hartford). Adding up only the top 50 MSAs served (those with populations over 1m) and 2500 miles would serve 90m people. That’s not bad.

So, what’s the takeaway here? Well, there are two. The first is that, as much as we want to build a multi-regional high-speed rail network, the Northeast Corridor is still, by far, the largest market for HSR in the country. The second, however, is that even when you exclude the Chicago-to-East Coast routes, the New York-to-Chicago Corridor should still be the third-highest priority to build. And if properly built (with top speeds of 200 mph or a tad more, especially across the flat land west of Canton) such a corridor could begin to compete with airlines, even on >500 mile routes.