In a factually-inaccurate-and-not-yet-corrected post, Michael Tomansky heard an anecdote (the Beatles made it from New York to DC in 2:15) and reported it as fact, claiming that it represented a golden age of American railroads which we will never see again. It most certainly is not: the GG1s the Pennsylvania Railroad rain in the 1960s were only capable of 100 mph as a top speed, and would have had to average 100 mph to get from New York to DC in that time (it’s quite nicely 225 miles in 2.25 hours). Scheduled times never fell below 3:30. 2:15? It didn’t happen. By the late ’60s, the Metroliners were running up to 125 mph on the corridor, with trains making stops clocking in at 3 hours and nonstops running in 2:30 once a day—it turns out it makes sense to stop in Philadelphia and Baltimore. Acela Express trains now make the trip in 2:45 making six stops; speed improvements could conceivably get this to 2:30, or to 2:15 non-stop (which is unlikely as intermediate stops cost only a few minutes and account for a lot of ridership).

But the fact of the matter is that before the Metroliners, there were very few trains that eclipsed 60 mph average speeds. Many streamliners of the ’40s and ’50s ran between 55 and 60, and a few, notably the Twentieth Century Limited and one of the Pennsylvania’s New York-DC runs, broke the 60 mph barrier. (The site linked has decent schedule information; easier than combing through the 1000-plus page Guide to the Railroads.)

The notable exception to this is not a single train, but a competitive market: from the late 1930s through the early 1960s, three separate railroads ran five trains per day between Chicago and Saint Paul at damn near—and in one case, over—70 miles per hour over a distance of over 400 miles, with several stops. (It was another half hour, after a long stop and at slower speeds, to the trains’ termini in Minneapolis.) In fact, for two decades between the beginning of World War II and the opening of the Shinkansen, they were likely the three fastest rail trips over 200 miles in the world. Here a good primer on the competition and the Chicago-Minneapolis schedule from 1952:

9:00-2:30, Morning Zephyr, 431 miles, 66 mph (in 1940: 6 hours, 72 mph)

10:30-6:05, Morning Hiawatha, 410 miles, 58 mph

1:00-7:15, Afternoon Hiawatha, 410 miles, 66, mph

3:00-9:15, Twin Cities 400, 409 miles, 65 mph

4:00-10:15, Afternoon Zephyr, 431 miles, 69 mph

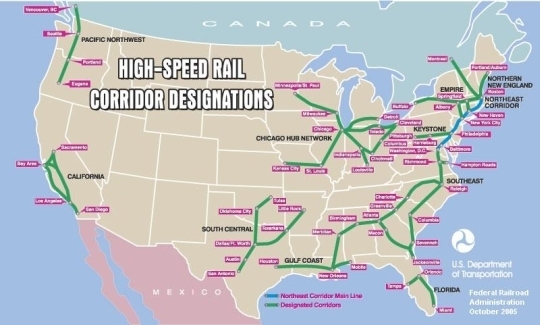

There were several other trains, including overnight options, each day, and these five schedules which could get you between the Twin Cities and Chicago in barely the time it takes to drive today (without traffic). Today’s Empire Builder runs the route in 7:45, at a respectable 55 mph, but nowhere near the 70+ of yesteryear (between some stations, the trains averaged over 80 mph, stop to stop; runnings speeds well over 100 were not uncommon). So while railroad speeds have slowly increased on the East Coast, it’s the rest of the country that has seen speeds come down: in particular, the Twin Cities to Chicago market.

Why did this route have faster speeds than anywhere else? Part of it is geography. Each line had its advantages, but none had many tight curves or long grades, and there were few intermediate stops to slow the trains. But part of it is competition: not with car or air travel, but with each other. Nowhere else was there a similar three-way competition over this distance. Once one railroad established the 6-hours-or-so benchmark in the mid-30s, the others quickly followed suit, and it proved to be good business. They kept the speeds in to the 1950s, when regulations bogged down the railroads, and subsidies flooded road and airport construction; the trains slowly disappeared in the 1960s. Today’s Empire Builder follows several different pieces of the former roads.

In another country, there never would have been three trains plying the same route. French railroads were nationalized in the 1930s, and Germany and Japan’s railroads were decimated during the war and rebuilt afterwards. If American railroads had been similarly nationalized or had the same sort of investment, there’s a chance that the three competing railroads could have combined resources to build a single, higher-speed line: all had rolling stock capable of over 100 mph, so five or perhaps even four hour trips would have been possible even without electrification. However, after the war American railroads did not see government investment (we certainly spent more money rebuilding railroads in Europe than we did in the US) and without a time advantage over airliners or interstates, trains that averaged near 70 mph, and except for one line on the East Coast, haven’t come back.