The great Livable Streets Alliance shared a story on their Facebook page about how pre-emptive MBTA shutdowns are a new phenomenon in Boston. They asked if we agree with the decision, or if we think the T should keep the system running as long as possible. I started posting a long answer there and later decided that it belonged here. With pictures.

Pre-emptive shutdowns are not a bad idea in theory and certainly make it easier to reopen the system. Some sort of shutdown is probably beneficial, but the T may have overreached in this instance and shut down the system for a longer period than absolutely necessary. And that should be the real question: is it absolutely necessary to passenger safety and the integrity of the system to shut it down? If so, where and when? And whether the system is shut down should be the answer to these questions. In this case, I think that the answer was certainly that, yes, for a time much of the system needed to be shut down. (We’re talking mainly about rail transit; bus service is far harder to run on unplowed, narrow, snow-covered streets.) But the T was probably shut down longer than necessary, and should have a better policy in place to ensure the least possible interruption to service.

In the case of the recent storm, there were three main areas where the T could have kept service running better:

- A later shut-down

- An earlier resumption

- A “snow map” with underground service

A later shut down:

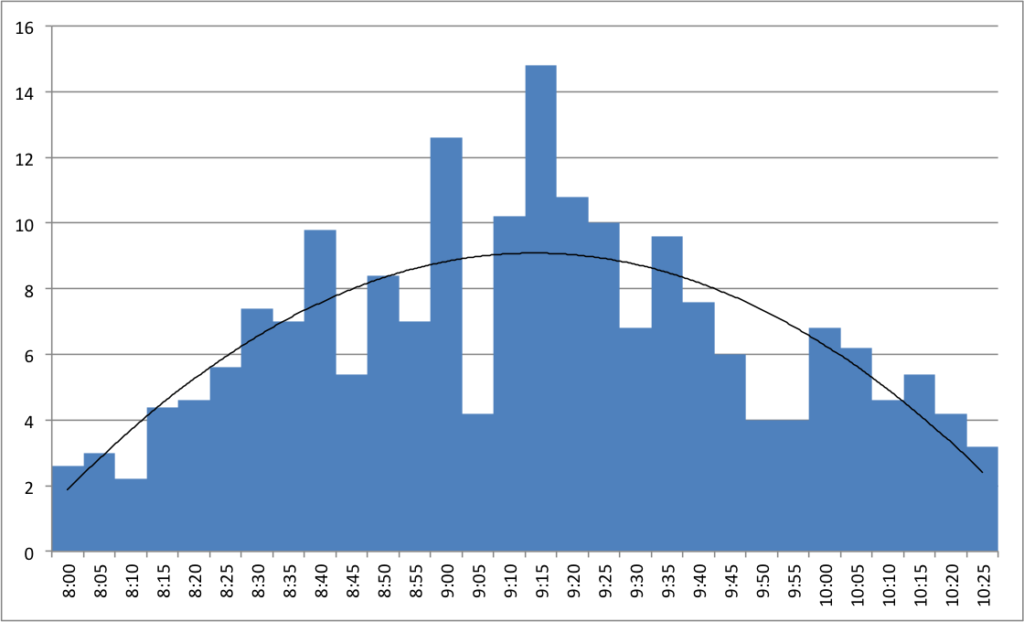

The transit was shut down early in the storm. At 3:30 p.m., the snow had only been falling for a few hours and only a couple inches coated the ground. In addition, forecasts had predicted the heaviest snowfall for later in the evening—starting around 7 or 8 p.m. Part of the issue was with MBTA employees being able to get home, and not wanting buses to be stuck on the roads. However, MBTA employees could certainly have been deemed “essential” and allowed to drive on the mostly-empty roads, and the T could operate limited service with employees who lived near transit lines later in the day. Since trains ran all night, employees who lived near rail lines could be shuttled home on these non-revenue trains after the end of revenue service. The T could have even put up essential employees in downtown hotels (which might be glad to provide reduced rates if it meant their employees could get to and from work). And obviously there were some employees who ran these trains overnight. Something along these lines would take some advanced planning on the part of the MBTA, but with several days notice before the snowstorm they could have made sure that there was staff on hand to provide minimal service until at least 7 or 8 p.m.

An earlier resumption:

A major fault in transit service was that it took more than 24 hours after the end of the storm for travel to resume. Certainly part of this was due to the

communications tower in Quincy going offline, and obviously there should be redundancy built in to that system. That’s a long-term structural improvement. But trains were operating without this tower (albeit at lower speeds and without passengers) to keep the lines clear. And I’m sure that riders would have been happy to have had service earlier, even if trains had to run more slowly because of the communications issues.

Another issue is snow clearance. At many underground stations, especially on older parts of the system, there are open stairways (Central Square comes to mind) which drifted full of snow and would be impassible. Exposed platforms would be more cause for concern. Still, it seems that the T waited until the driving ban was lifted before sending out crews to shovel these stations. Considering that it was operating trains throughout the storm, it could have had crews riding between stations Saturday morning, clearing snow as the storm ended and getting service ready for resumption by that afternoon. T employees could certainly be deemed essential and allowed on to the roads earlier.

Some stations are partially open but partially covered (for instance, along the Southwest Corridor portion of the Orange Line). During initial resumption of service, two- and four-car trains could be run while the ends of the platforms were cleared so that service could be run even if the stations weren’t fully shoveled. The situation should be triaged ahead of time. When there is going to be a very heavy snow accumulation—on the order of two feet or more—the T should know which areas will need to be cleared to provide any service, and which are lower priority.

A plan could be put in to place to first clear stations with a maximal cost-benefit ratio for the amount of effort needed to clear the snow and the number of customers served. For instance, the Southwest Corridor of the Orange Line could be prioritized over the outer portion of the Blue Line, since its stations are mostly covered and only portions of platforms would need clearing, and since its ridership is higher. With the prevalence of social media, service could be phased in with frequent announcements as stations reopen.

A “snow map” with underground service:

Washington, D.C. receives only about

a third the snowfall of Boston on average but every few years has a big dump (or, in the case of the winter of 2009 to 2010,

two big dumps). The Washington Metro is not designed for operation in heavy snow and will partially shut down when there is more than 8 inches (which, while an annual—and sometimes weekly—event in Boston, occurs once every three years in DC, and a foot only once every eight years). However, the system is partially underground, and those sections are

kept functional during storms.

The T doesn’t have the same issues that DC has—MBTA cars have no issue running during storms and keeping the tracks clear. How do I know this? I went skiing during the storm and saw plenty of trains out and plenty of clear tracks. Tthe T even

posted video of trains running during the storm. In fact, in 1978, the trains apparently didn’t run (the T was an all-PCC fleet back then, and those smaller-lighter cars may not have been as useful for clearing snow) and the T had to roll out a

1907-vintage snow plow to clear the tracks:

That’s an amazing photo, and apparently it was taken three days after the snow stopped falling. And it took six hours to plow the line. (I think the only thing that’s changed in this photo is that the overhead wire has been replaced with a

catenary.) Even if the trains are running and the tracks are clear, it takes some time to clear off platforms so that people can get on to the trains. When it snows faster than crews can clear, which was certainly the case in this storm, a shut-down makes sense.

|

| Tracks are clear at Longwood Station on Saturday morning, but the platforms are still buried. |

|

Skiers stride Beacon Street on Saturday as a snow clearance train rolls by.

Service would not resume for another 24 hours. |

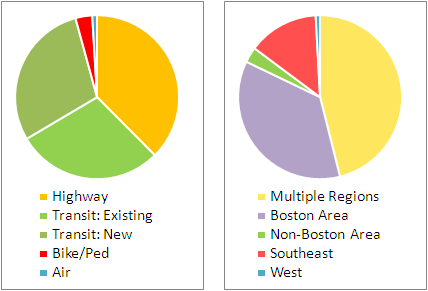

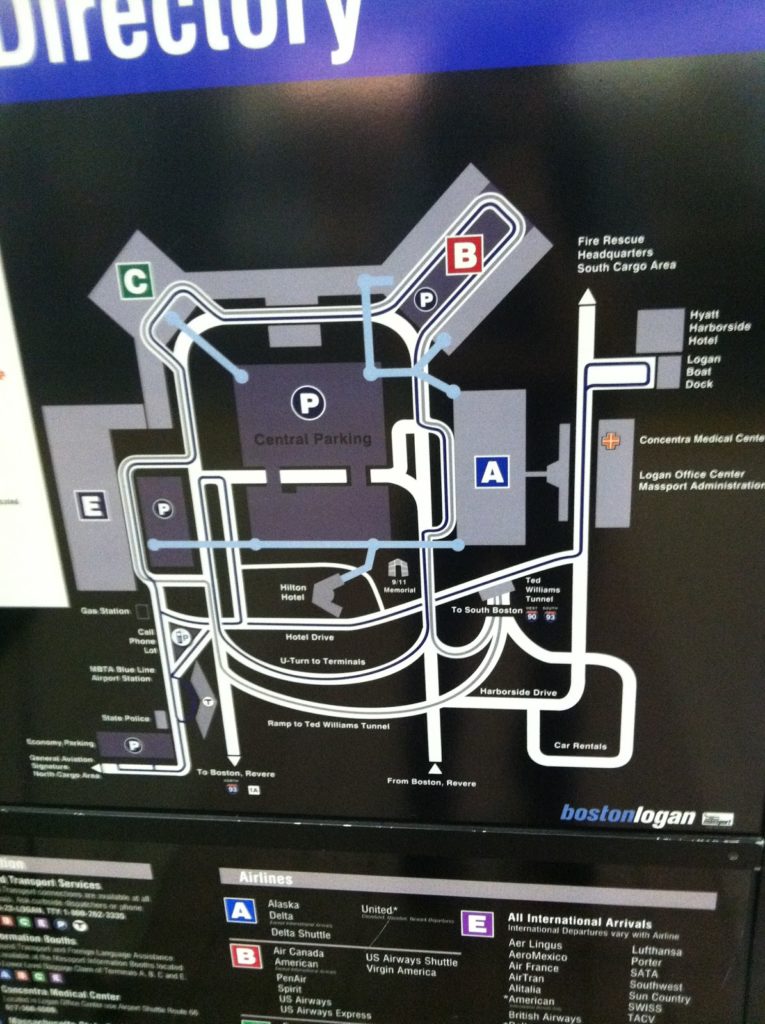

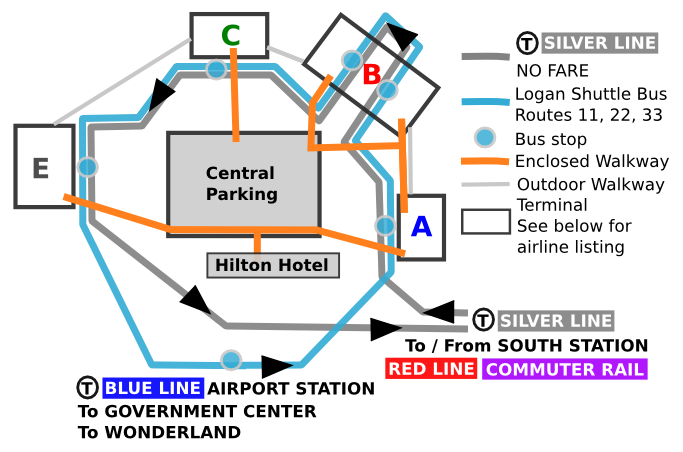

But what about the underground? The core segments of the MBTA run in tunnels, which are, by design, impervious to snow. Most stations have covered entrances, and those which do not could be top priority for shovel teams (Central Square, for instance), or have uncovered entrances temporarily closed (the Church Street entrance to Harvard, for example, or the auxiliary entrance in Kendall closer to the river). Intermediate, uncovered stations (Charles is the only one which comes to mind) could be temporarily closed, and the system could be run on a limited basis. For example:

Would this serve everyone? Certainly not. But it does provide service to several important areas, including downtown, Back Bay, Kendall and the airport. It also provides service to near major hospitals which are, of course, open through the storm. (The platforms at Charles could be shoveled to provide service to MGH.) Keeping this much of the system operational—with all-night service in the case of a road travel ban—would be a huge show of good faith by the MBTA and would quell most of the complaints that they aren’t doing enough to keep service running. It would also serve many travelers who have no other option during the storm. It, too, would take some advanced planning, but would provide better service.

I hope that, for the next storm, some of these steps will be taken. For instance, if service was better matched to the start of heavy snow and run through rush hour, then curtailed to underground portions of the system for the storm and then phased back in during the afternoon on Saturday, there would have been many fewer complaints about the overall storm service on the MBTA. This is not to say that the T didn’t do a good job—having full service on Monday took quite a concerted effort. (In addition, overall kudos to MassDOT: the highway shutdown meant that,

unlike in New York, cars were not stranded in snow drifts on main highways.) It would be nice, however, to have a better plan of action for future storms.