Game three at Target Field, looking east.

I managed to catch one of the games in the first series at Target Field in Minneapolis this week (my Red Sox were in town) and although the Sox lost, it was great to see a new stadium. It was actually the second in a week—I was at Kauffman Stadium in Kansas City last weekend for a Sox game (nice ballpark, in the ‘burbs surrounded by a sea of parking, and I didn’t have time to explore KC)—and it was very interesting to see how the park is sited, and how people are adapting to the new experience, both inside and out.

From a baseball perspective, it’s fun to see how people like the inside. I was born and raised on Fenway, and the Metrodome was, um, atrocious. After a Sox loss there, I was depressed. Watching my team get shellacked on Thursday, having skipped out of work, with the sun beating down and the cool breeze blowing, well, it was nice. There are some cute features (the two baseball players—Minnie and Paul—shaking hands across the river when a home run is hit or the game is won), the usual odd angles of a new ballpark, and no baggie in right field. And the view of the skyline is a great touch. Otherwise, it’s a perfectly good replacement for what was a perfectly poor excuse for a baseball stadium.

But this isn’t a baseball blog.

The geographic term “site and situation” is usually applied to whole cities or settlements, but it can really be used to describe the location of nearly any geographic feature. And with 40,000 people, Target Field (or any baseball stadium) can be described as a small city for three (or, in a Red Sox-Yankees game, four and a half) hours at a time. Basically, the site is physical characteristics of, in this case, the stadium. Situation is how it interfaces with what is around it; how it connects to other buildings, roads and transit.

Of all the arenas cities build to glorify their teams (or their selves), baseball parks generally see the most traffic. A football stadium may seat 70,000, but it only sees 10 games a year. Even with other events, such a stadium is hard-pressed to break a million fans. (There’s a good reason football stadiums are often, and maybe should be, built away from downtowns: their demand for parking does not mesh well with surrounding land uses, and moving that many people in and out can strain all but the best-equipped transit systems.) Indoor arenas, even when the combine basketball and hockey, sell out shy of 20,000, and there are only about 80 games a season. That’s 1.6 million. Add in some other shows, and you can break two million. (The Staples Center in LA, with two basketball tenants, may see more fans, although I can’t imagine Clippers games sell out.)

But baseball parks? They usually seat at least 40,000 (most new parks are around this figure). And they have 81 home dates a year. Throw in a few concerts, and you can bring more than three million fans in each year. From an economic development standpoint, baseball stadia are probably the best generator of people in sheer numbers. Even if they don’t have anything beyond baseball, they still bring in more visitors than any other arena.

Of course, the Metrodome didn’t do much for its surroundings. Much as it was 28 years ago, it is surrounded by, well, mostly by parking lots—a suburban stadium in the middle of a city (or, at least, a tangle of highway ramps). Target Field, for many reasons, may not suffer quite the same fate.

Target Field’s Site

Target field sits on a not-quite square plot of land on the northern fringe of Downtown Minneapolis. The street grid in Downtown is oriented to the Mississippi river, which flows five blocks to the site’s east. South of Hennepin, the grid is shifted slightly, but where the ballpark is located, the streets run almost perfectly 45˚ off of the cardinal directions (i.e. NE-SW and NW-SE). Before the ball park was constructed, there was a ditch between 2nd Avenue N and where 4th Avenue N would run. The southeastern half was taken up with the exit ramps of Interstate 394; the rest was a parking lot until it reaches the railroad tracks. The stadium is built above the former parking lot, with a pavilion extending above the railroad tracks.

The park is oriented due east—that is, the batter is looking straight at the rising sun and the pitcher throws the ball to the west. To fit the field in the confined location, the stadium needed to be oriented in a cardinal direction, and baseball stadiums are best located to the northeast. Baseball games are rarely played at sunrise, and this allows for the smallest chance that the sun will be in a player’s eyes. (Although there are two baseball stadia which are oriented due west—and they sometimes have to suspend play at sundown.) With baseball games starting in the afternoon (with one exception, the 11:05 a.m. start for the Patriots Day game in Boston), some parks face south of east, and some due north, but most face northeast. Here’s a great diagram of all the ballparks. And, in case you were wondering, this orientation is set forth as “desirable” in Major League Baseballs rules (1.04).

There’s another major reason for the orientation of the ballpark, but we’ll explore that in the situation discussion. Other than the fact that the stadium is built on stilts over a highway and a railroad (and, in the future, a bike path), there’s not much else exciting about the ballpark’s site, since it is basically reclaimed land (discussions of sites for cities often go on for much longer, incorporating terrain, water sources, deep harbors, rail corridors and the like). Basically, it’s a rather cramped city block in Minneapolis.

Target Field’s easterly orientation gives is a grand view of the Minneapolis skyline; it should be even better at night.

Target Field’s Situation

The situation of the ballpark—how it interfaces with the rest of the city—is much more interesting. The orientation, which is a site feature, is, perhaps, more importantly, part of the park’s situation. The reason that the park was sited facing east instead of north is the proximity of Minneapolis’s skyline—the highest buildings between Chicago and Seattle—sits to the southeast of the field. A northerly facing diamond would have nothing in view beyond the stadium’s walls. With the east-facing ballpark, several 800-foot-tall buildings loom less than half a mile above the field (and, yes, you can see in from the higher floors of some of them).

In fact, Target Field is significantly closer to the center of Downtown Minneapolis (we’ll define it as the IDS Center) than the Metrodome. As the crow flies, the nearest gate to Target Field is about a quarter mile from Nicollet. The Metrodome is more than twice that distance. There is quite a bit less surface parking around Target Field, too. Minneapolis has a lot of parking downtown, and, for the most part, these spaces are empty nights and weekends—which is precisely when they are needed for baseball. The Metrodome was almost completely surrounded by surface parking, while Target Field has only a few nearby surface lots.

This lack of surface parking is going to have several interesting effects on the parking market. First, the land near the Metrodome will lose much of its value for parking as the parking for the Twins and Vikings will be disaggregated. The Twins drew 2.4 million fans in 2009, many of whom parked in these surface lots. While Vikings fans will need somewhere to park, there are only about 600,000 Vikings fans, one fifth of the pre-2010 total. If the real estate market picks up in Downtown Minneapolis (one of the few under-construction buildings in the city is on a former parking lot near the Dome), these lots—especially the ones a bit further from the Dome—will net less cash from parking revenue, and thus be more likely to be sold for development.

Around Target Field, the parking situation is a bit more developed. Minneapolis has a many car commuters, and, thus, a lot of parking structures (and some surface parking). The Central Business District is strong enough that it is not infiltrated by surface parking, although there is a good deal on the flanks. The city operates three “ramps” (as parking garages are called here), called the ABC Ramps, which surround the field, have direct freeway access, and about 7,000 parking spaces (assuming 2.5 passengers per car, that’s half the stadium). There are, of course, dozens of other garages downtown, and even some surface parking. With the Target Center (home of the basketball Timberwolves—the hockey Wild play in Saint Paul) and several theaters nearby, the events parking market is rather well established, and there may not be a need to claim more land for parking. However, the few surface parking lots nearby will become more valuable as parking, which may hamper redevelopment efforts in the neighborhood, unless the ballpark increases their value as developed land.

The Twins, who originally played at suburban Metropolitan Stadium (now the Mall of America) have decreased nearby surface parking with each move. Their original ballpark was similar to Kauffman or Miller Park in Milwaukee—everyone drives, and many tailgate. Thirty years later, they are now playing in a very urban-feeling environment.

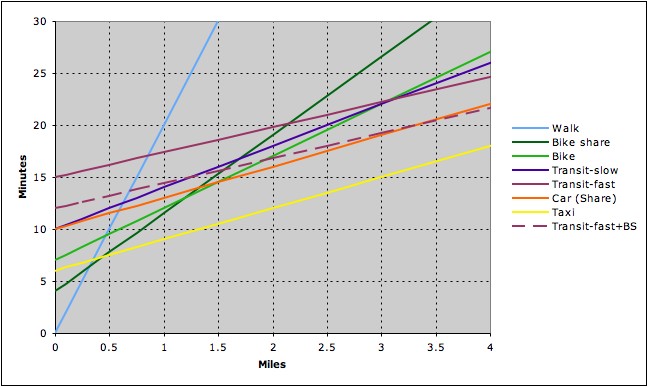

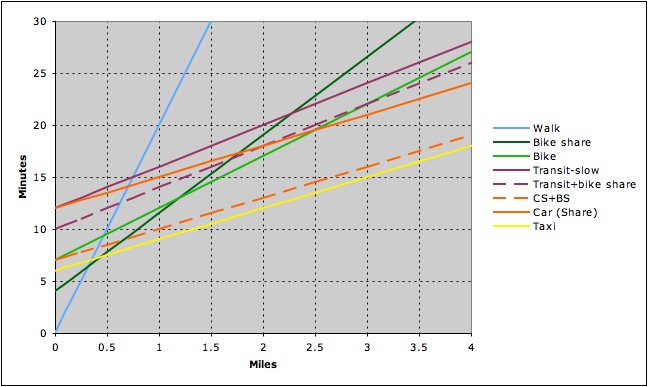

Target Field is also accessible by transit, and these connections are well publicized by the team and city, which hope to limit the volume of traffic around the stadium on game days. Amongst stadia with transit connections, there are actually few which are located as centrally on a transit system as Target Stadium, or at least as it has the potential to be. Stadia require quite a bit of land and, recently, quite a bit of parking, which are not generally compatible with the centers of transit systems. If you look at older ballparks (or former locations)—Fenway, Wrigley, Yankee Stadium, Shibe and Baker Park (in Philadelphia), Comiskey, Ebbets Field, the Polo Grounds—they are generally on transit lines, and far from the nexus of the transit system. Even in cities with new stadiums, like AT&T Park in San Francisco or the ballpark in Washington, D.C., the parks are generally not near main transit stations. In cities with major transit systems, land near major centers are just too damn valuable for a block of grass and stands which are only used 250 hours each year.

In other words, most baseball stadia require a transfer. They’re not near commuter rail terminal stations. They were built where there was cheap, vacant land, which, for older stadia, was usually a few miles out from the middle of the city. In Boston, this means that thousands jam the trolleys to Kenmore (when this coincides with the end of rush hour, for a 7:00 game, the trains are jammed). In New York, the two lines which serve the Stadium—the IRT Jerome Avenue Line (4) and the IND Concourse Line (B, D)—easily reach crush capacity, especially the over-capacity Lexington IRT which is already way beyond capacity (which is why they’re building the Second Avenue Subway), and the L to Addison in Chicago gets pretty full up to Wrigley.

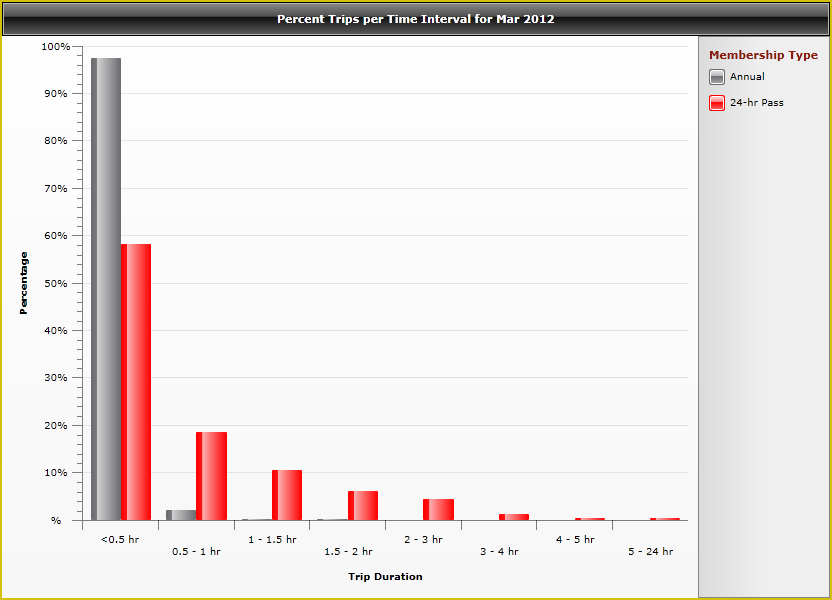

Minneapolis has one rather-well used transit line, which was extended a stop to serve the stadium. The light rail vehicles on the line are rather large, with a crush capacity of more than 200, meaning a two-car train can carry nearly 500 passengers. Right now, the stadium is at the end of the line, meaning that fans can pour in to empty trains, and as long as the end of the game doesn’t conflict with rush hour (any weekday day games begin at noon, likely in the hopes the game will end before the height of the evening rush) and the trains should be able to clear passengers out before the rush. For 7:00 games, baseball fans will be traveling against rush hour, which is desirable. On evenings and weekends, the trains are relatively empty—the line is rather commuter-oriented—so they an be mostly devoted to game traffic. And the line was designed to stop adjacent to the stadium to allow for ease of boarding and alighting. There are no stairs, escalators or treks to the station. Many bus routes also pass nearby or terminate near the stadium.

In addition to the light rail, a new commuter rail service serves Minneapolis and stops below the stadium. The 500 fans it can carry is small potatoes compared with the light rail (which can carry that many every few minutes) and it won’t even serve every game (it buys trackage rights from a very well-traveled section of one of the BNSF’s main transcontinental routes). However, it has large parking lots in the suburbs and special fares for ballgames, and appeared to be well-used this past week.

The line for the light rail was long, but orderly. Still, the boarding process needs to be streamlined.

There are definitely some kinks to work out. At the Metrodome, 4000 of the average of 30,000 fans came by train. Target Field seats 40,000 and should be sold out most of the season, and parking is harder and more costly; it’s presumable that upwards of 6000 fans will ride the light rail to the stadium. On Thursday, the line after the game was several hundred people long (but very orderly, as opposed to what happens in Boston or New York; it probably also meant that it was slower and that the maximum nuber of people were not filling the cars). MetroTransit had staff on hand, but did not have the vehicular capacity. In Boston, where the main sticking point is line capacity, the MBTA runs full rush-hour service before and after Red Sox games on the Green Line, and usually stores several cars in the Kenmore Loop, allowing them to run several trains outbound, one after the next, to deal with the post-game rush. Here, the line could support three car trains at three minute headways—700 people 20 times an hour—but was not utilized to that level.

MetroTransit needs to take heed. They have stub tracks beyond the station, and should have as many trains stored there as they can. With 300m of double-track, they should be able to have 10 cars—for 2500 people—stored there, although with two-car trains, only 8 cars for 2000 people may be feasible. They should then run these at three-to-five minute headways for the first half hour after the game. Additional cars stored just south of Downtown at the maintenance facility should be sent as quickly as possible, with boarding on both tracks. With the ability to run three-car trains, this would be a capacity of 8400 to 14000 per hour, more than enough to clear out the stadium traffic in 30 minutes after a game.

In the future, Target Field could become one of the most transit-centered ballparks in the country. Plans are moving forward to build the Central Corridor (to Saint Paul, 2014), and long range plans have these two lines, which will terminate at Target Field (thus doubling capacity through downtown), interlining through downtown with the Southwest Corridor (2015) and the Bottineau Transitway (to the northwest). With 7.5 minute headways (the current rush hour headways on the Hiawatha Line), 32 trains, each carrying up to 500 to 700 passengers, could pass Target Field each hour, carrying 16,000 to 22,000 passengers—more than enough capacity for the ballpark, and a capacity rivaling the transit capabilities of Fenway and Wrigley.

With ample parking in place and the possibility of increased transit service, Target Field may do a better job of drawing nearby development than the Metrodome. The Dome is in a no-mans land. It is surrounded by parking on all sides, and by freeways in two directions. Once transit showed up in 2004, its days as a baseball stadium were all but numbered. Target Field helps connect Downtown Minneapolis to the North Loop, a hodgepodge of new lofts, hip restaurants, and still-operational warehouses. It has a bit of parking, but most of this is a good distance from the ballpark, much further than the huge ramps nearby (thus, its value as parking won’t increase dramatically with the new ballpark). There is a rather obtrusive highway offramp between the stadium and the North Loop; however, if it were dismantled, would yield a plethora of developable land with half a mile of the Mississippi River, Downtown, transit and bicycle facilities. It is also slated to have a line of Minneapolis’s proposed streetcar network pass through it. The North Loop could benefit greatly from being linked to downtown by the park, which bridges the former two-block-wide trench between the neighborhood and the downtown with rather wide pedestrian concourses, and be further developed as a transit-oriented, mixed-use neighborhood, where there are currently underutilized light industrial plots or warehouses within a mile of downtown.

Finally, with Minneapolis currently the top bicycling city in the country, I’d be remiss to not mention the stadium’s situation regarding cycling. And walking. As far as walkability, the ballpark is a few blocks from Hennepin and, while not connected to the Skyway system (which are used more in the winter than summer) it is better connected by sidewalks and by the new pavilion built between the ballpark and the Target Center.

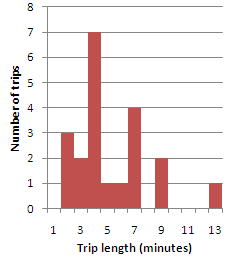

Ten minutes before game time (and ten minutes before the sun came out), the bike racks at the field were full, even though it had rained lightly in the morning. Several other similar racks line the stadium walls.

As for cycling, Minneapolis probably has more people who bicycle to baseball games than any other city. The bike racks at the Metrodome, which was actually located near more bike trails than Target Field, were always well used, but they were tucked away on one side of the building, away from most of the trails. The field is surrounded by bike racks (map [pdf]), including racks which line the northwest promenade of the field—built over the railroad tracks—and when I visited this week, they were all packed. Perhaps the Twins need to install some more.

In addition, the Cedar Lake Bike trail, which extends in to downtown from the southwest, is being extended under the ballpark. It will connect the bike trail along the Mississippi River to the stadium, and allow grade-separated bike access to the stadium, avoiding foot and car traffic. With these improvements, the bike facilities near Target Field will be unparalleled in the major leagues. (And, no, when I was living a similar distance from the ballpark in Boston, I never even thought of biking to Fenway.)

With easy transit options (a bus straight from my house; a nice bike ride along the river) and a lovely field I do want to see at night, I’ll be back.