|

| An article so bad a whole page of letters was needed to point out all its flaws! |

A few weeks ago, the Globe Business section wrote about Kendall Square traffic, barely paying lip service to transit and cycling (and ignoring the fact that most of the complaint was in regards to a construction project which will rehabilitate the 30-year-old infrastructure which is falling apart). The article was rightfully called out by no fewer than eight letters (one by your’s truly)—the entire back page!—in the opinion section.

To follow that up, today future Boston2024 spokesperson and cheerleader-in-chief Shirley Leung writes a completely misinformed, Jim Stergios-esque piece about transit privatization, which demands a full line-by-line refutation (sometimes called a “fisking“). So, here goes (original in italics, my comments not):

It costs the MBTA a staggering $20 per passenger to provide late-night bus service. At that rate, the authority might as well hand out cab vouchers.

This is true, if you look at no externalities, which is something business writes don’t know about, I guess. If you look at increased transit trips before the late night service begins, it shows that providing later service increases transit use earlier on as well. Additionally, increased late night service helps the local economy (more people out spending more money) and especially the low-wage service workers who are required to run it and don’t have to shell out for expensive taxi trips.

But if the T can be cut free from the state’s antiprivatization law — which Governor Charlie Baker and Speaker Bob DeLeo are proposing to do — it just might be able to operate a night owl service that makes financial sense.

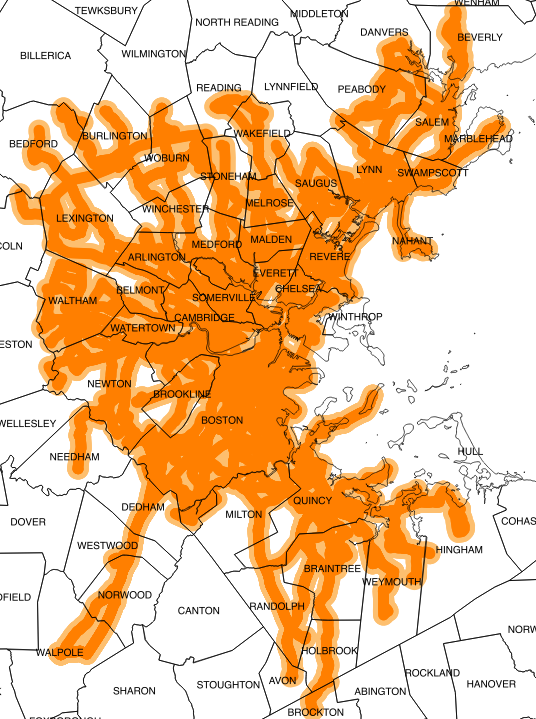

One of the reasons the Night Owl service costs what it does to run is that service is more heavily used in certain areas, and less-so in others. So, what are we going to do? Operate only a couple of routes that have a lot of riders (the Red and Green lines, basically) and not operate to lower-income areas where people actually need the service?

And here’s how: Get someone else to run it.

Now, I know the mere thought has members of the Carmen’s Union and their supporters in the Senate fuming, but let’s not make privatization the bogeyman — or for that matter, the system’s savior. The T has plenty of functions that are privatized, from commuter rail to ferry service, with varying degrees of success.

The major T service that is outsourced is Commuter Rail. You know, the system that took a month and a half to return to service after the snow (the subway took weeks less), canceled trips without telling the higher-ups at the T and stranded passengers. That one? That’s the model?

No one is proposing to outsource all bus or subway operations, but the T needs more flexibility in order for true reform to take root. In other words, we can’t keep the same handcuffs on if we ever want to escape our miserable transit past.

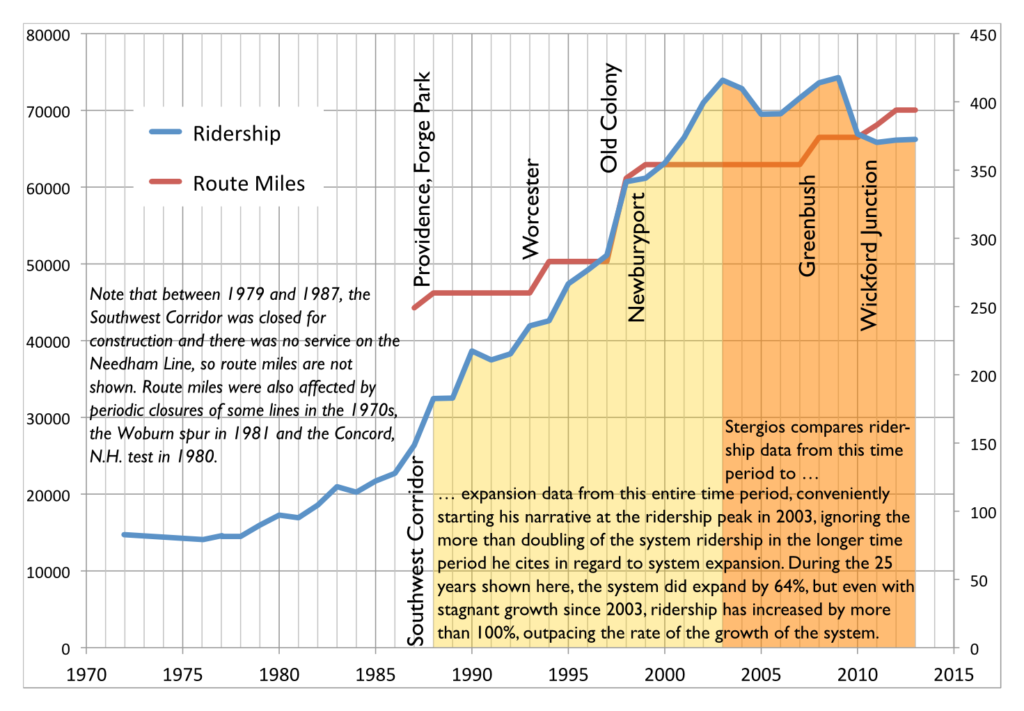

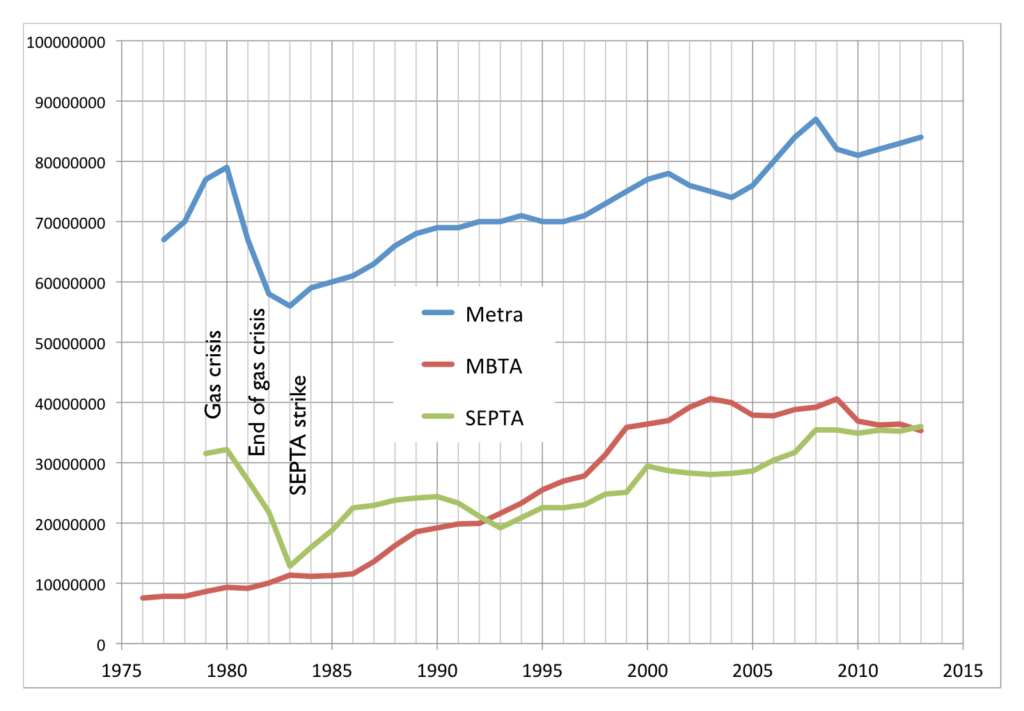

Our “miserable transit past.” The one that has seen ever-increasing ridership despite aging infrastructure and car-centric planning. The snow this winter was not only unprecedented for Boston, but for any other major city anywhere in recorded history. Apparently Sweden had similar accumulations in 1965 and the rail system was shut down for two weeks.

“I am not saying privately run services are a panacea,” Transportation Secretary Stephanie Pollack told me. “They are a tool, and they need to be an option.”

The antiprivatization statute, known on Beacon Hill as the Pacheco Law after its primary sponsor, Senator Marc Pacheco of Taunton, was created in 1993 in reaction to Governor Bill Weld’s privatization initiatives. The law, pushed through by public employee unions, makes it difficult for certain Massachusetts agencies to contract with private firms for any work being done by state workers. Baker is proposing to free the MBTA from the constraints of Pacheco, while DeLeo’s version calls for a five-year suspension of the statute.

So let’s get back to the example of late-night service, and imagine what Pollack could do if the Pacheco law no longer applied to the MBTA.

Yes, let’s imagine.

Last year, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority launched with much fanfare a one-year pilot to extend train and bus service until 2:30 a.m. on Saturdays and Sundays. Fares do not cover the cost of running the T, but the subsidy on late-night service is substantially more. For example, a typical bus ride costs the MBTA $2.74 per passenger, while the cost for late-night service is nearly eight times the amount.

Most late night rides are on the subway, which costs the T significantly less per passenger (about $1). The $2.74 figure is for bus trips only, and includes all trips: rush hour service is far more efficient, breaking even on some trips, while evening and weekend service, with less patronage, has a greater subsidy.

It’s more expensive because the agency is using its full-size 40-seat buses at night when there are fewer riders.

This could be said for middays, evenings, weekends and holidays, too. Most late night service is provided by trains, which is why it’s much more popular than the 2001-era bus-only service.

What’s more, the buses run on a schedule designed for daytime commuters.

No. They don’t. Only a few buses run at all late at night, and all routes operate at far less frequent schedules than at rush hour. The 111, for example, runs every three minutes at rush hour. It runs every 15 minutes during late night service. That’s one fifth the service.

Freed to do what it wants, the MBTA could hire an outfit like Bridj, the upstart Boston transit service that employs 14-passenger bus shuttles and designs demand-based schedules.

Despite their posturing, Bridj currently runs specific routes which change intermittently but not based on real-time demand. 14 passenger vehicles might not be enough for late-night service on some routes, so they could theoretically replace only some routes. (Bridj will respond that they have some “special sauce”—their words, not mine— to deal with this but I’ll believe that when I see it; for now it’s a fixed route system.)

The savings come from being able to adapt to a nighttime business model.

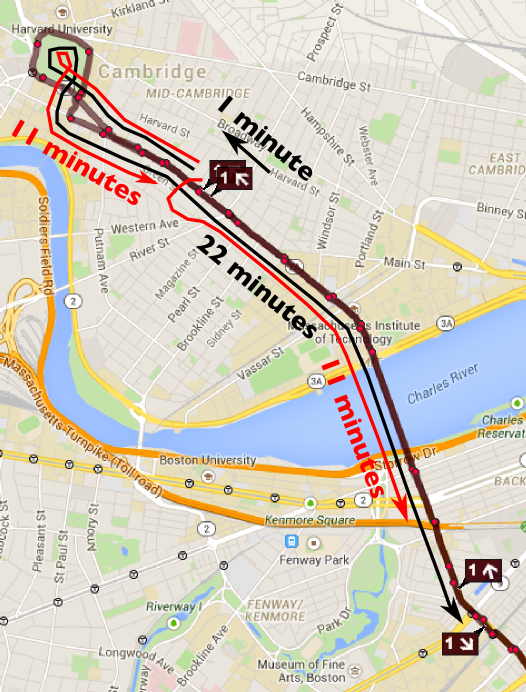

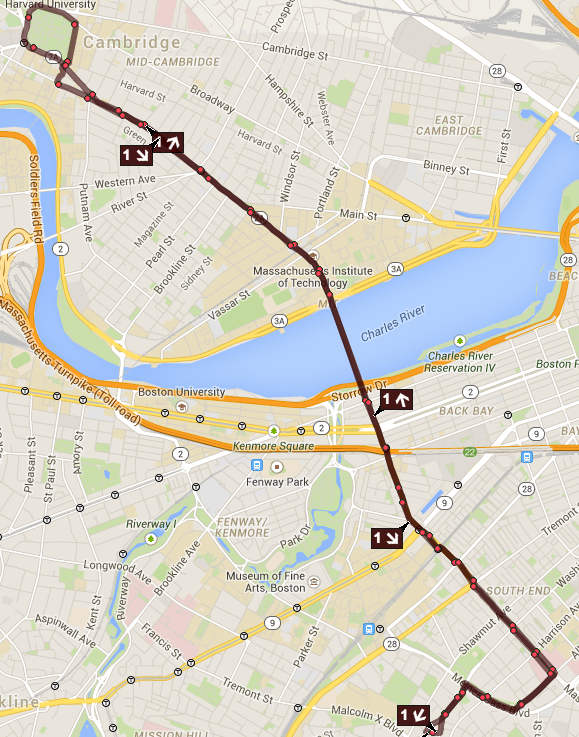

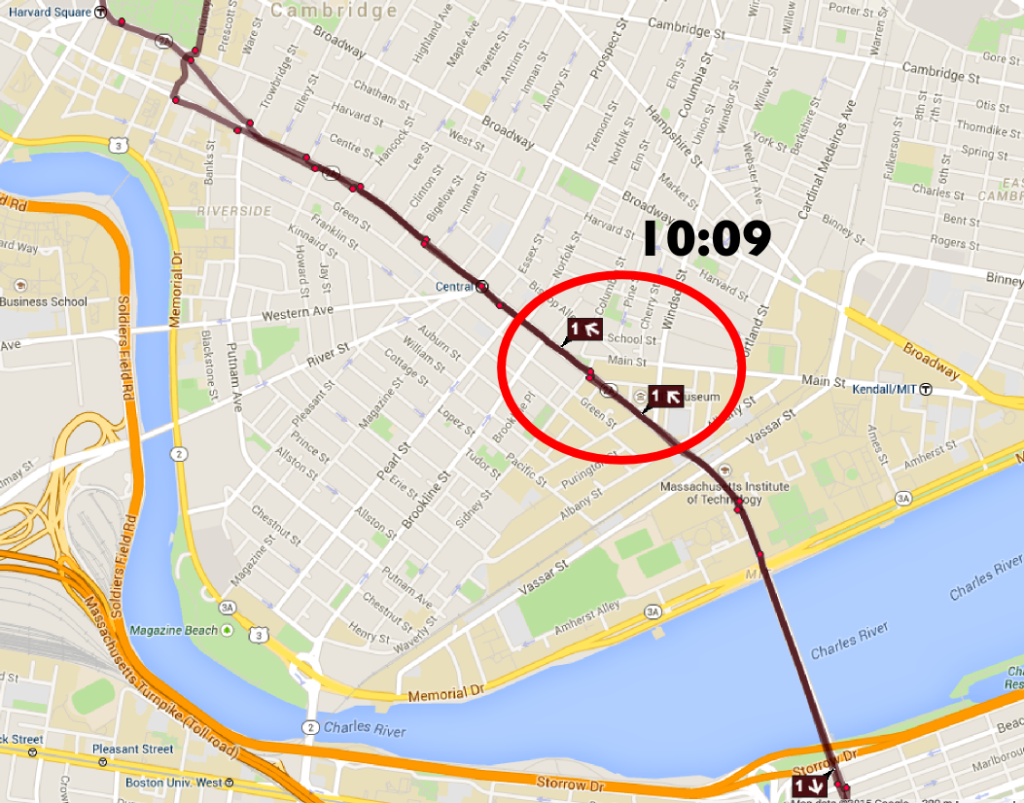

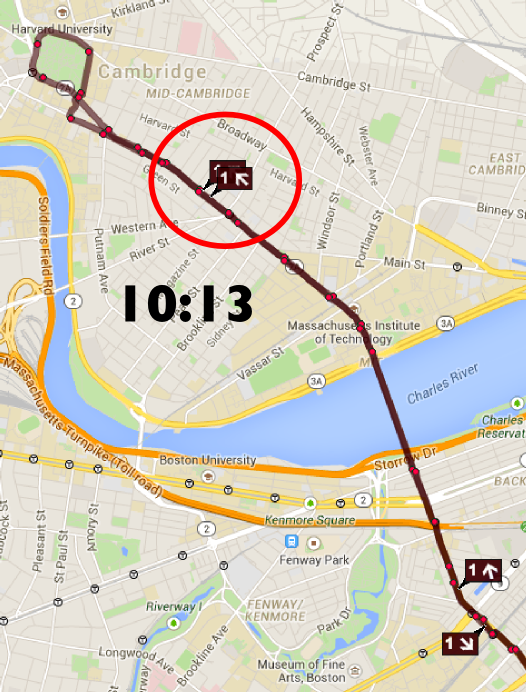

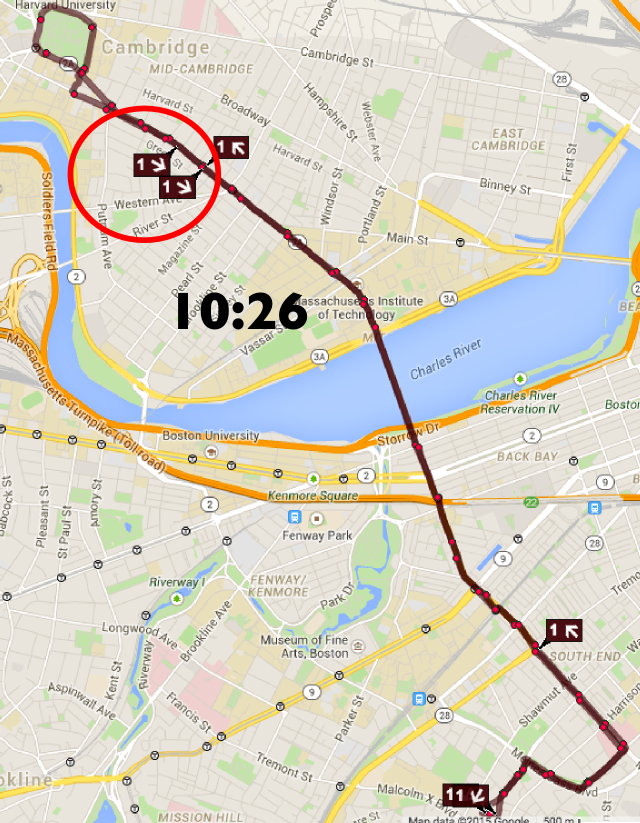

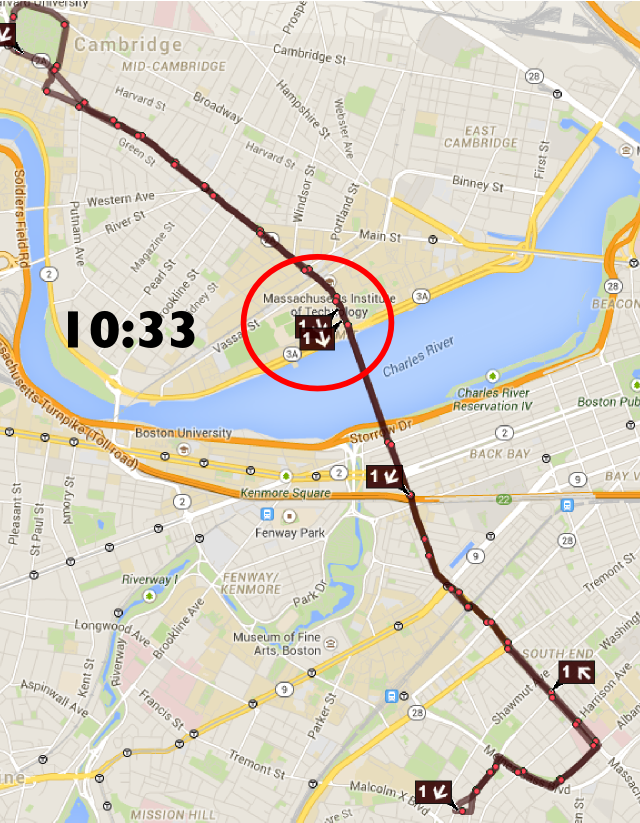

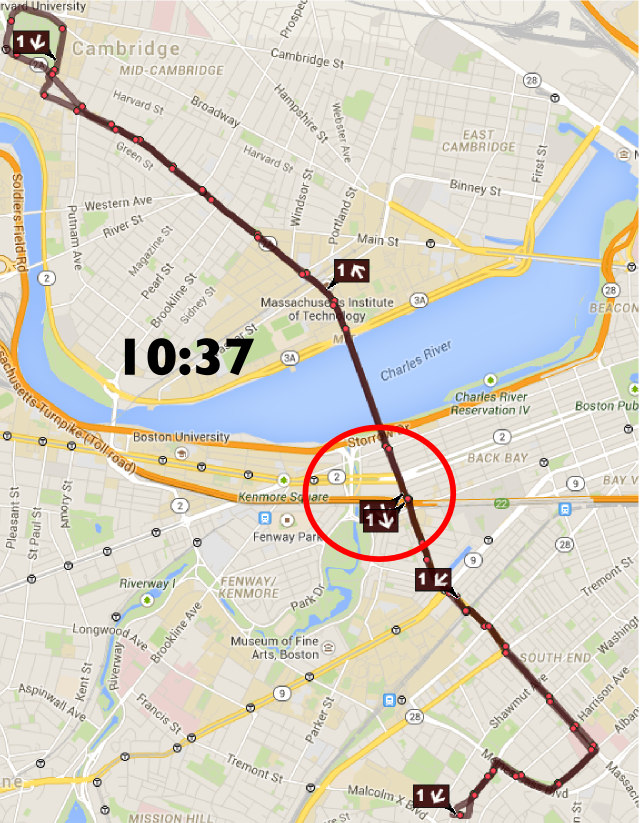

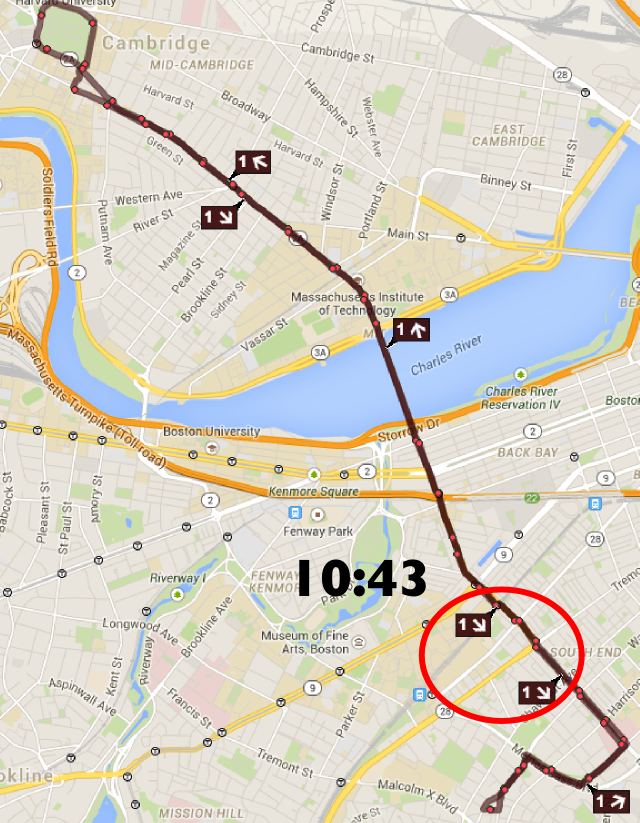

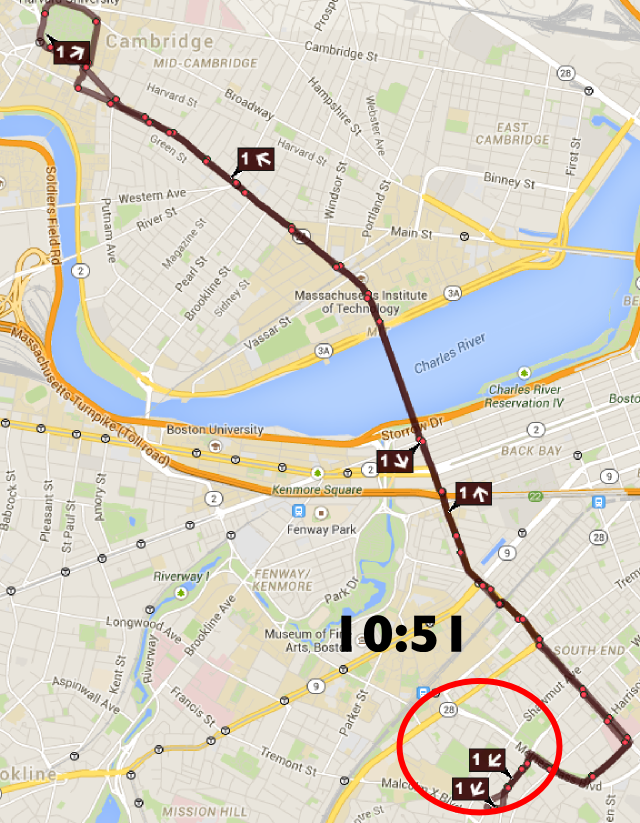

Which is going to be a heavy lift for them. Currently, the T’s late night service carries about 10,000 passengers each day of late night service, in approximately two hours (5000 passengers per hour). Right now, Bridj carries maybe 500 passengers each day during morning and evening rush hours over approximately five hours (1000 passengers per hour). So we’d be asking them to scale by 5000%, which is a lot, considering they’ve added minimal service since they began a year ago (and have cut back service as well, although this goes mainly unreported). Maybe they could supplement service on a few outlying routes, but it’s unlikely they’d replace the transit system wholesale, so any savings would be minimal.

But the opportunity to use partners like Bridj goes beyond providing a special service. Similarly, the MBTA could save money by outsourcing bus routes with low ridership — and there are many of them. For example, one route in Lynn makes nine trips a day carrying a total of 45 people, which means on average of five people are riding that bus.

Oh, Shirley. The route that Leung is referring to is the 431 in Lynn. It makes nine round-trips per day between Neptune Towers, an affordable housing development in Lynn, and Central Square. Some of its trips are pull-outs from the garage: a bus leaving the Lynn garage, rather than operating out of service, picks up passengers along a route it would already be serving. All trips are interlined with another trip (usually the 435). It operates a total of 1:22 each day, so at $162 per hour (the T’s hourly cost for bus operations) it costs about $220 to operate per day, discounting the fact that some trips would operate anyway since on pull-outs and pull-backs. Most of the trips are run in downtime between other trips, so instead of paying a driver to sit at the Lynn busway, the T provides service to an affordable housing development nearby, so the marginal cost of the service is quite a bit lower.

And how would another provider provide this service? Each round trip takes 10 minutes. Will a private operator pay a driver to sit in Lynn for an hour, run a 10 minute trip, and then sit in Lynn for another hour? Is that efficient? It could be argued that a smaller shuttle could make the trip back and forth to Neptune Towers more frequently, and that may be true. But that type of service is not really one the T provides, nor should it be one; the 431 is the case where the T has an otherwise idle bus for a few minutes and uses those to provide additional service at a minimal extra cost. This should be applauded, not derided.

This is a very good illustration of what I would call the “end of route” fallacy. If we imagine the 431 as an extension of the 435 bus (which, for all intents and purposes, it is), Leung sees an empty bus near a terminal point and assumes the whole line is empty. The 435 carries 900 passengers on a typical weekday between Lynn and the Liberty Tree Mall (making 16 round trips, so 28 passengers per trip in each direction). Leung is only looking at the 45 passengers it carries on this short extension. It’s akin to the people who say “that bus comes by all the the time and there’s never anyone on it” and then you find out they live one stop from the end of the route and by the time the bus reaches its destination it’s packed full of passengers.

There’s a further comment here: the T operates a few such routes which never see terribly high ridership but serve specific populations and are politically unfeasible to cut. One one end of the spectrum is a route like the 431, or the 68 in Cambridge. The 68 is never full, but it provides service between to Red Line stations to Cambridge’s City Hall annex and library, and is thus politically important. (The 48 bus in JP is a great example; its 85 riders each day were not happy to see it go.) Then there are train stations like Hastings and Silver Hill in Weston. They only have a few riders per day, but those riders are the “right” riders. Cutting these routes, in the grand scheme of things, saves very little money compared to the trouble it creates.

The 68 and 48 might be examples where the T could contract out services, but they are small potatoes compared with the rest of the system. Most every T route requires a larger bus at many times during the day. (88% of routes and 92% of trips are on routes which average at least 15 riders per trip—obviously more at rush hours—a size above which an operator needs a Commercial Driver’s License and commands a higher salary.) And since buses can’t magically switch from a 14 foot cut van in to a 40 foot transit bus, it would mean more time deadheading back and forth from bus yards at different times of day. Is that efficient?

But eliminating Pacheco is not just about saving money. It can also be about improving service. Yes, the MBTA could actually add routes with the help of private partners.

Yes, maybe we’d get back the 48, and the 68 would operate with smaller buses. There are maybe 10 routes the T operates which could conceivably see service with smaller vehicles to meet demand at all times. They account for two or three percent of the service. By the time you outfit those small vehicles with compatible fare equipment, ADA access and otherwise make them interoperable with the T, it makes sense to just cut your losses and operate a one-size fleet.

That’s what most excites Bridj founder and chief executive Matt George — the ability to bring his idea of flexible mass transit, well, to the masses who ride the MBTA. When he launched Bridj last summer, he never considered it competing with public transportation.

Good thing they don’t have an ad at the station in Coolidge trying to lure commuters away from their crowded (read: efficient) commute to a smaller, less crowded (read: less efficient) vehicle. While Bridj is often secretive about their numbers, sometimes they let stats slip, and it’s not the rosy picture they paint publicly. For instance, they claim that 20% to 30% of their riders are “new to transit”, while the other three quarters apparently are lured off of other services. And again, Bridj, which operates about 50 trips per day in Boston, has a capacity of about 700 passengers (if every seat of every bus is full, which is not the case), or about 0.05% of the MBTA. It’s quite possible that their shuttle buses actually operate more miles than the cars and taxis of the few people who weren’t riding transit beforehand.

“We are in a supplementary position,” George said. “We are neither set up nor we are interested in wholesale taking over anything.”

Which is good, because they’re not about to. But right now, they “supplement” peak hour transit, which is when the T does well for itself and likely makes a profit. (Oh, and a lot of it runs underground, so it doesn’t create more congestion.) It’s those pesky other times of the day and week that lose money, but provide necessary service. The T, in a sense, supplements itself.

Another big idea from Pollack is to look at whether the MBTA should own and maintain its rail cars and buses. Perhaps the state should look at whether it’s more cost-effective to lease — and require the manufacturer to maintain those vehicles.

What’s that sound? Is it a bird? Is it a 40 foot CNG NABI? No, it’s the Pioneer Institute being wrong about something, again!

That, in one fell swoop, attacks two problems. The T cannot keep up with maintenance of the existing fleet and infrastructure, with a $6.7 billion backlog of repairs that is growing. It also has come under fire for spending $80 million annually on bus maintenance, nearly twice as much as other transit agencies, according to an analysis by the Pioneer Institute, which blames the high cost on overstaffing.

This site has published a full refutation of the Pioneer Institute’s report. Let’s just say that their data analysis is specious at best and intellectually dishonest (okay: lies) at worst. The T spends less on bus maintenance than New York, and only 40% more than other large transit agencies (not 100% more). That 40% could be made up with better management practices (which should be investigated) and with capital investment in the T’s maintenance infrastructure. While other cities often have large, indoor storage yards and new maintenance facilities, many of the T’s date back nearly a century, and most buses are stored outdoors. More to come on this soon.

Here are some more numbers from the Pioneer Institute to chew on. Unlike the MBTA, the regional transit authorities — from Springfield to Lowell — can outsource. They spend, on average, $6.38 per mile to operate their privatized lines, compared with the MBTA, which spends $16.63 per mile to run its bus routes.

Has Leung seen the service provided by some other RTAs? Many run much smaller vehicles already, so it shouldn’t be surprising that their services are cheaper to run. Service is much more limited; many RTAs run service only until early evening and few run any service on Sunday at all! Likewise, the service they do run is rarely near capacity, and crush-load buses puts much more wear-and-tear on the physical infrastructure of the bus. A fully loaded bus carries 50% of its weight in passengers. Imagine driving a Toyota Corolla with five 200-pound people crammed in to it, and 400 pounds of luggage in the trunk, versus two people. Do you think that the overloaded car will need new tires, shocks, struts and a transmission (not to mention use more fuel) than the one with one or two people and a suitcase in the back seat? This is an apples to oranges comparison.

The fear of privatization comes down to taking away somebody’s job. If that’s the case, the Senate should work up a compromise to make sure union drivers are at the wheels of private buses.

Fine, but then expect the costs to not save that much money, since there are added costs (more yard space, more out-of-service operation) to those operations to eat in to any savings.

A reprieve from the Pacheco Law would go a long way to fixing the T. But, as the governor told lawmakers last month in defense of his broad plan to shake up the T, if nothing changes, then nothing will change.

A reprieve from Pacheco will make at most a very small dent in a few services the T operates. It may reduce costs by 20% for 10% of the buses the T runs. That would be one half of one percent of the T’s total budget. Is that really worthwhile? There are certainly places where the T could be more efficient. But except in a few cases, this is not a real solution, but anti-government mumbo-jumbo.