We recently wrote about the obscenely inflated cost of the Red-Blue Connector. And while the underground costs are certainly inflated, it still involves building a tunnel underground, in loose fill, under a busy street, and then building connections in to an existing station. It would still involve months- if not years-long lane closures, massive utility relocation, and underground station construction. It might be heretic to say so, after Boston has mostly removed above ground transit, but in this case, an elevated solution might be the best solution possible, and not just because it would be cheaper (which it would be).

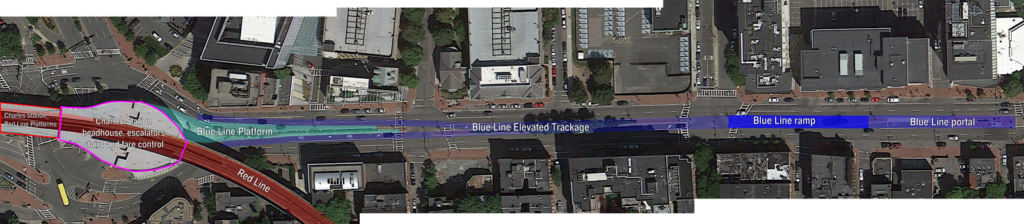

First, the logistics. The Blue Line tunnel currently ends several blocks east of Bowdoin Station. The original portal was between Joy and Russell Streets (at Nims Square, one of Boston’s lesser-known squares). Here’s an aerial photograph of the portal; you can see that it is several blocks east of the curve at Bowdoin Station. Most likely, the tracks were capped just east of Joy Street, and the portal filled with dirt and built over. Most likely, it still exists.

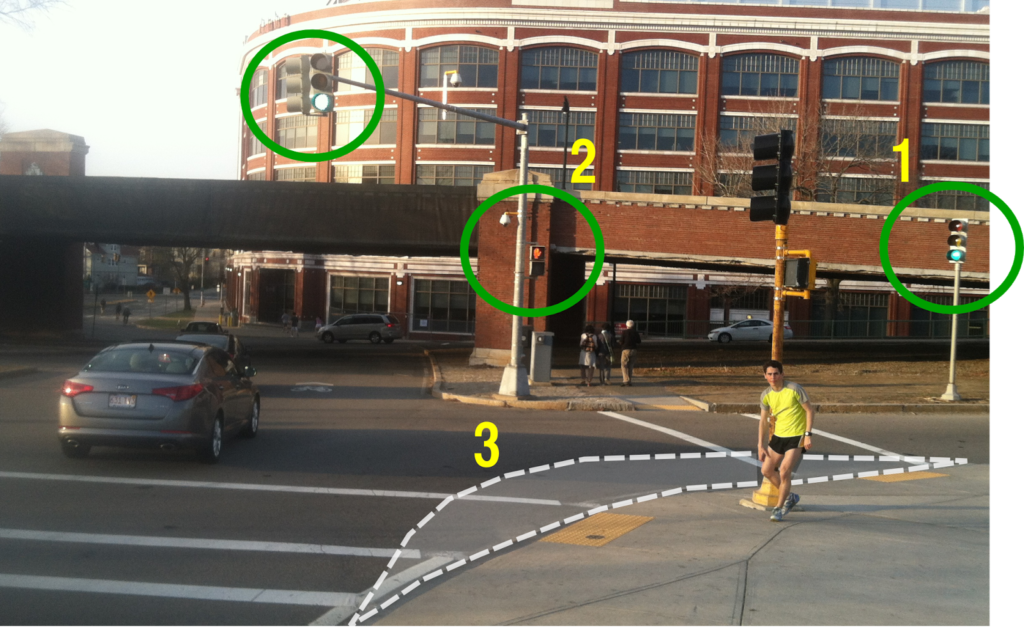

And most likely, it could be easily opened. The cheapest option would be to run the Blue Line straight down the center of Cambridge Street at grade, but for a litany of reasons that, uh, wouldn’t work. But instead of coming up from underground and flattening out, it could continue sloping upwards and, by Blossom Street, enter an elevated guideway above Cambridge Street. From there, it would continue a few hundred feet and terminate at a two-track station with a center platform above Cambridge Street, adjacent to the current Charles Station.

Click the diagram below to enlarge. All lines are to scale.

There are many, many advantages to an elevated solution. They include:

• The portal exists! There may be some utilities buried there, but not likely major infrastructure; it’s probably mostly just fill.

• The portal is built in to the side of Beacon Hill. As the tunnel rises to the surface, the surface falls away. This limits the space that a ramp takes up for the transition from underground to elevated. In addition, because the Blue Line does not require overhead wiring, the tunnel height is lower—and therefore the floor is higher—reducing the amount of climb necessary. A similar subway-to-elevated transition exists for Green Line trains between North Station and the Lechmere viaduct. The distance between the portal and where the viaduct passes over the ramps from the Leverett Circle is conveniently the exact same distance as from Joy Street to Blossom Street on Cambridge Street.

• Once above the street, the viaduct will be quite narrow. Since the East Boston tunnel was originally built for streetcars, Blue Line cars are narrower than, say, Red Line cars. The elevated portion of the Green Line between North Station and Lechmere—especially the new section east of Science Park—is a good guide to the width, although with no need for overhead wire, a Blue Line viaduct could actually be built narrower than the Green Line.

• Charles Station could be built to serve the Blue Line with no added mechanical equipment, and minimal changes to the station. There are already wide stairwells, escalators and elevators in Charles Station which bring passengers from street level to the Red Line. The Blue Line would simply be a platform accessible from the current outbound platform, and would not require any additional infrastructure. Unlike other transfer points in downtown Boston, Charles Station was recently rebuilt, and passages are wide enough for significant additional traffic. An underground station, with additional elevators and escalators

• An elevated Charles Station would require transferring passengers to climb and descend fewer stairs than an underground solution. Imagine a round trip from Cambridge to East Boston. For an underground station, passengers would arrive on the Red Line, descend to street level and then down to the underground, reversing the trip on the way back for a total of four flights of stairs. For an elevated solution, the morning would require two flights—down to street level to cross under the Red Line and then back up—but the evening would be a level transfer, halving the vertical distance each passenger would have to travel.

• While Cambridge Street abuts the historic Beacon Hill neighborhood, it is generally bordered by newer construction, and in many cases by parking lots. The street runs east-west, so most of the shadows cast by an elevated structure would fall on the north side of the street, which is mostly occupied by Massachusetts General Hospital, and in several cases by parking facilities. As a major beneficiary of the project, MGH would likely be willing to have some shadows cast in exchange for far better accessibility. In addition, Cambridge Street already has an elevated structure at Charles Circle, so it is not an entirely new concept to have overhead transit in the area.

• A fire station would likely have to be relocated from the south side of the street between Russell and Joy Streets as they would no longer be able to take left turns across the subway-elevated transition. However, it could be moved to parking facilities on the other side street near MGH, and integrated in to new construction. For instance, a fire house occupies the ground floor of a skyscraper in the Financial District.

• Elevated construction and stations are far less expensive to build than underground. And far less distuptive. While an underground structure would require years of lane closures on Cambridge Street, an elevated structure would require only supports to be built in ground—and those would be in the median. Most of this work—exploration, utility relocation and the pouring of the concrete—could take place outside of rush hours, and the actual viaduct could be built off-site and placed on the pedestals, with minimal interference with local traffic. If the area can survive a three-year closure of the Longfellow Bridge, it could deal with a few short-term lane restrictions.

At $100 million per mile, the elevated section would cost less than $50 million to build. Since the station would be little more than a concrete slab between two tracks—no need to install multiple elevators, escalators and fare control—it would not appreciably add to the cost. It’s entirely possible than an elevated solution could be built for under nine figures, far, far less than the state’s estimate for an underground connection.

• This project would require few—if any—property takings. The only street-level construction would be supports for the elevated, and these could be built in the existing median on Cambridge Street. Again, the supports for the Green Line connection between Science Park and North Station is a good case study; the base of the concrete pedestals are only five feet wide.

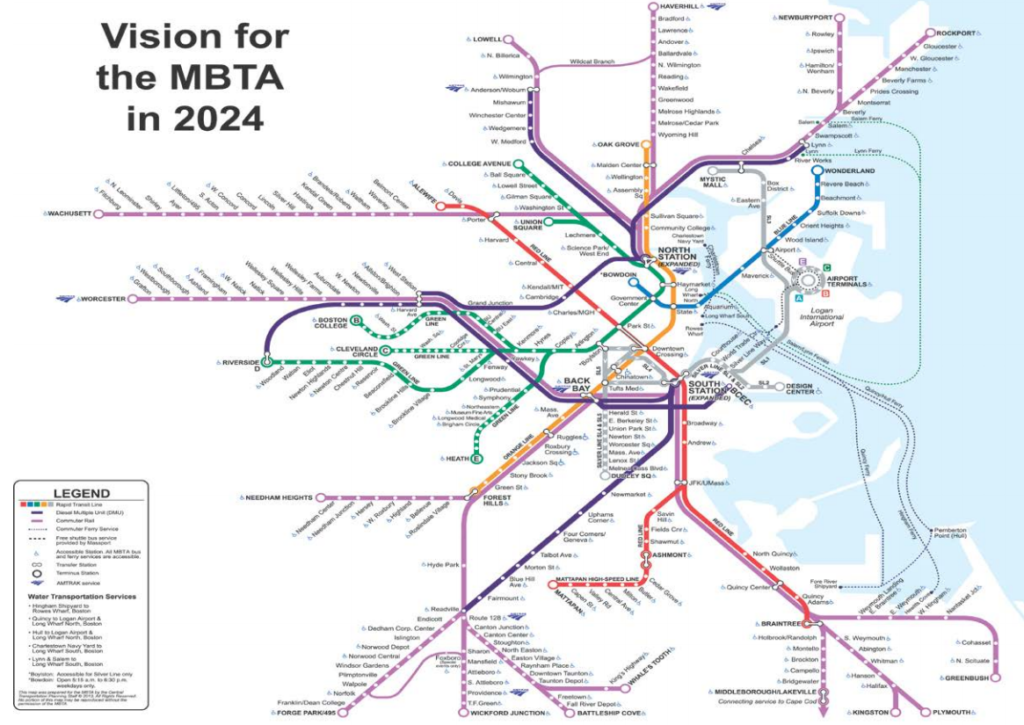

Building a Red-Blue connector is something which would dramatically enhance Boston’s transportation network. It would increase ridership, reduce congestion downtown, and provide better employment access for a large part of the area. It would also utilize the only portion of the downtown network which is under capacity—the Blue Line—and allow it to better serve the traveling public. And while the state may be set on inflating the price to high that it will never be built, a compromise solution using as much existing infrastructure as possible could be built more quickly and far less expensively. It is a solution the city and state—and stakeholders in the area—should seriously consider.