|

State of the art computer modeling? Yes.

Common sense? No.

Better service? Time will tell. |

UPDATE! Schedule changes postponed!

The MBTA’s new schedules are out for the North Side Commuter Rail. The changes are … interesting. There are good parts, especially for Fitchburg and Newburyport riders. There are bad parts (things people won’t like), especially for people used to less-crowded short turns, and some bizarre service gaps which impact the shoulder periods of rush hour. And then there are ugly parts—parts that just don’t make any sense—that show that the process was not fully thought out. Unfortunately, it will probably take some time before this is changed, and require some public outcry for this to occur. A consultant and a computer model were used for these schedules, but common sense seems to have been left by the wayside.

Tl;DR:

Good news for

- Newburyport branch riders

- Outer Haverhill riders

- Fitchburg line except Lincoln, Concord, West Concord

Bad news for

- Rockport branch riders used to every train being express

- Rockport branch reverse commuters

- Swampscott, Lynn and Chelsea

- Inner Haverhill riders, especially Wakefield

- Winchester, Wedgemere, West Medford

- West Concord, Concord, Lincoln

|

| Visualizing changes at North Station |

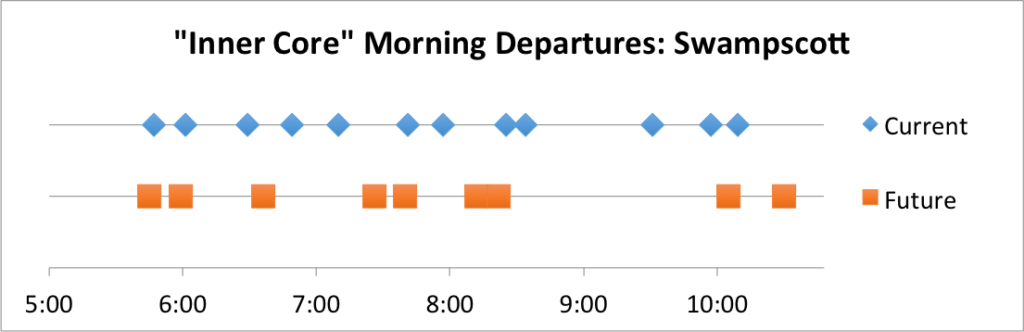

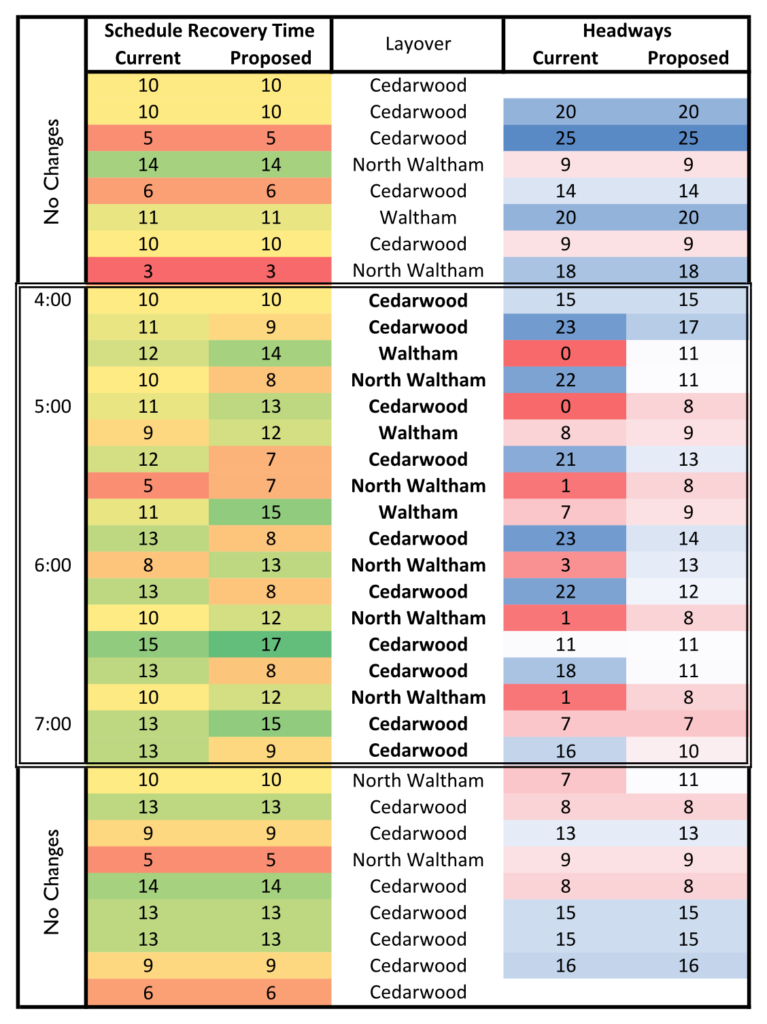

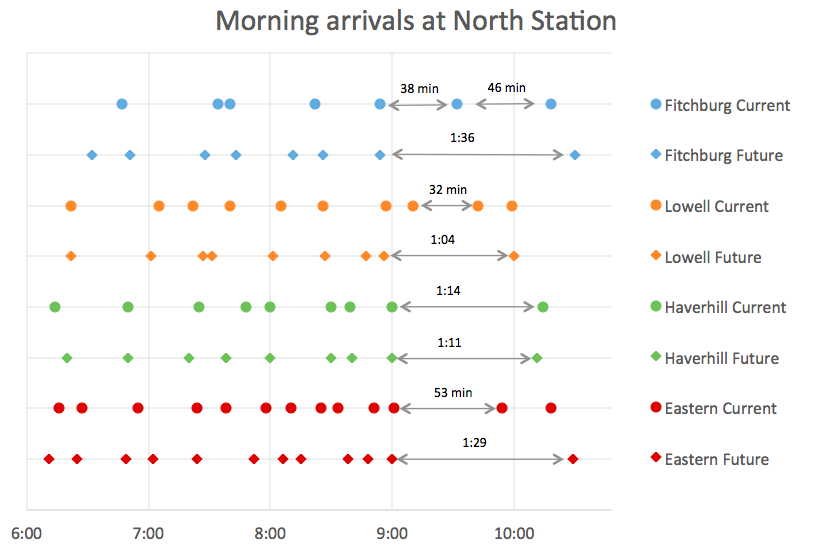

The most blatant example of this is the timing of the schedules: there are no trains—on any line—arriving at North Station between 9:00 and 10:00 a.m., and none which depart North Station between 6:30 and 7:25 p.m. So for anyone who works a 10 to 6 shift is completely hosed. This needs to be fixed. If no one rode these trains, I could see the logic. But people do. MassDOT counts these sorts of things. Some trains in the 6:45 range carry 400 customers. Let’s not make them all drive, mmkay? Each line should have a “catch-all” train: a train between frequent peak service and infrequent midday and evening service that arrives North Station around 9:30 and departs around 7:00 to fill those gaps. Just because the T defines rush hour as ending at 9:00 and 6:30 doesn’t mean demand shuts off entirely at that point.

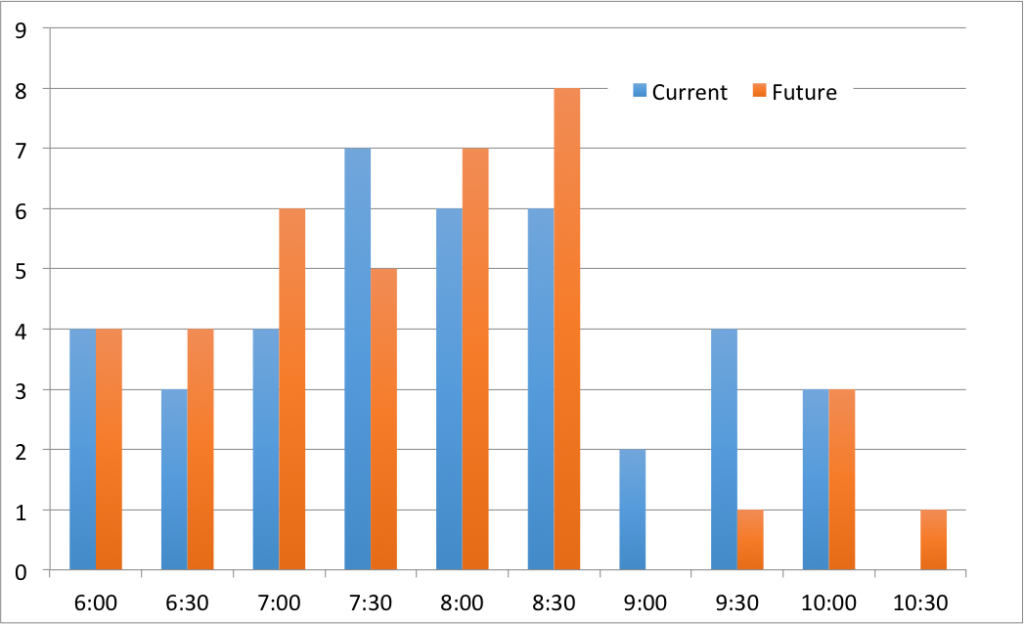

Here’s another thing: right now, arrivals and departures are somewhat spread out, so that passengers on connecting services (read: the Orange and Green lines) aren’t all riding at peak hours. In case you haven’t noticed, the Orange and Green (and Red and Blue, for that matter) lines are, uh, full. These schedules will mean that more passengers will funnel in to North Station between 8:00 and 9:00, when the trains have less capacity, rather than spreading service out later in the morning when there is some more space on the Green and Orange lines.

And weekend service is still anemic: most lines have gaps between trains of three hours. Why would anyone take the train? Hourly service should be a goal.

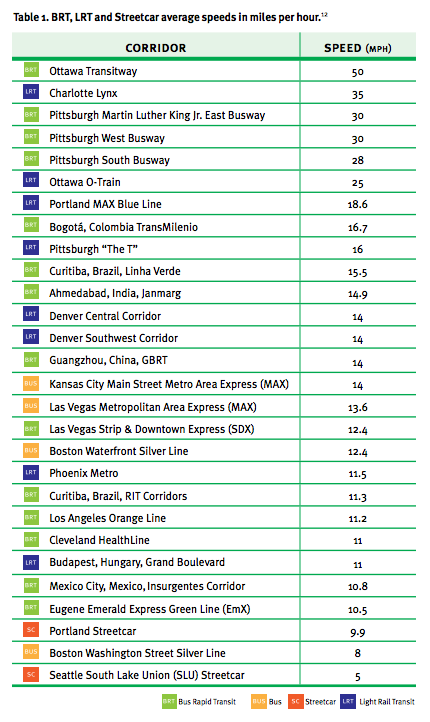

Let’s also take a quick look at some of the T’s stated goals with this schedule change, and whether they are being met, in particular, page 7. (The PDF can be found here.)

* Increased Peak Train Service. In general, this is attained.

* Additional Peak Express Service from Outer

Points. This is attained, but often at the expense of service to inner core stations.

|

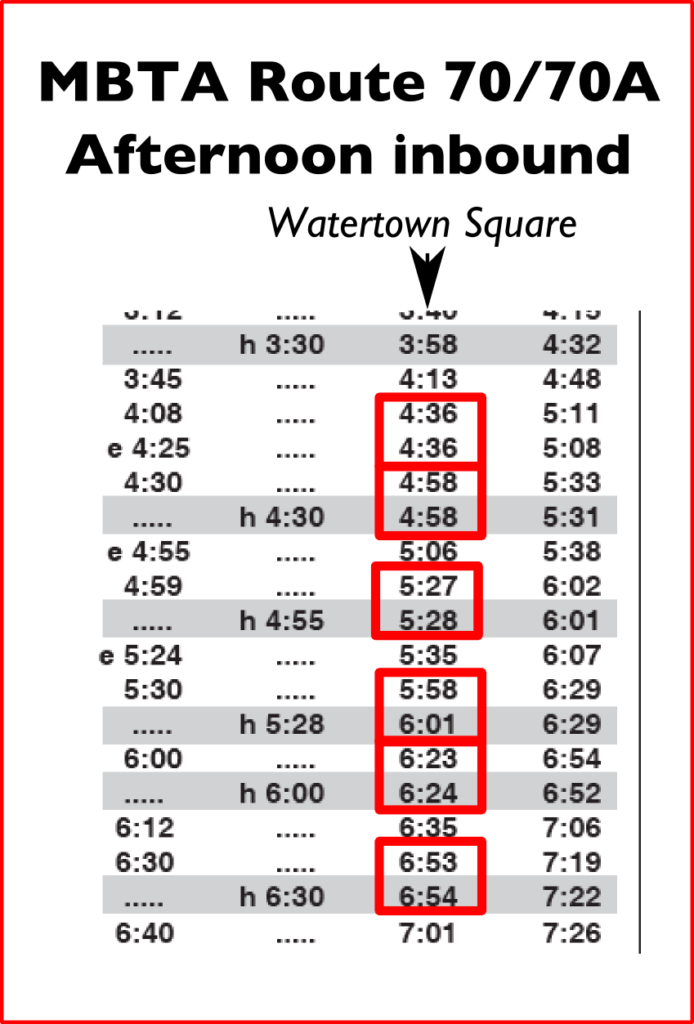

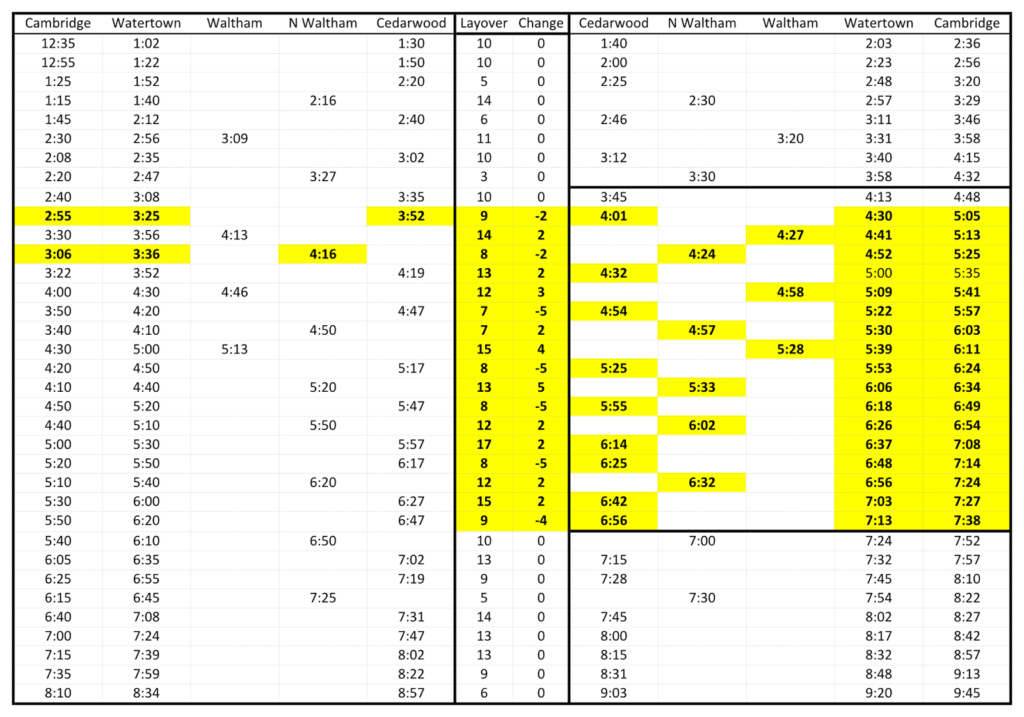

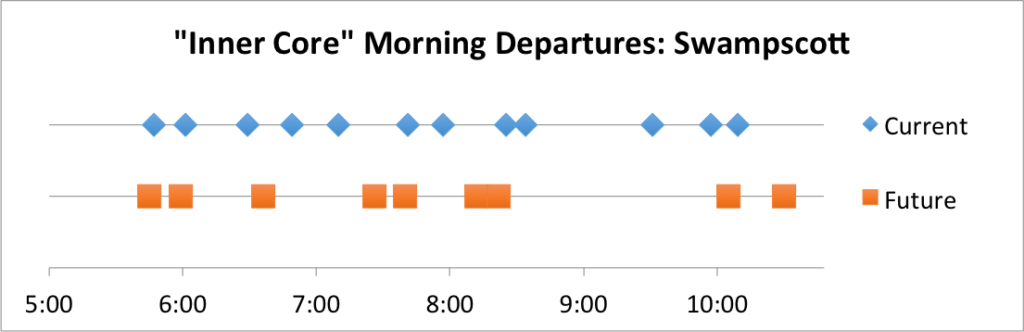

Does this look more evenly spaced to you?

Current: Average service gap 25 mins, standard deviation: 13 minutes

Future: Average service gap 35 minutes, standard deviation: 30 minutes |

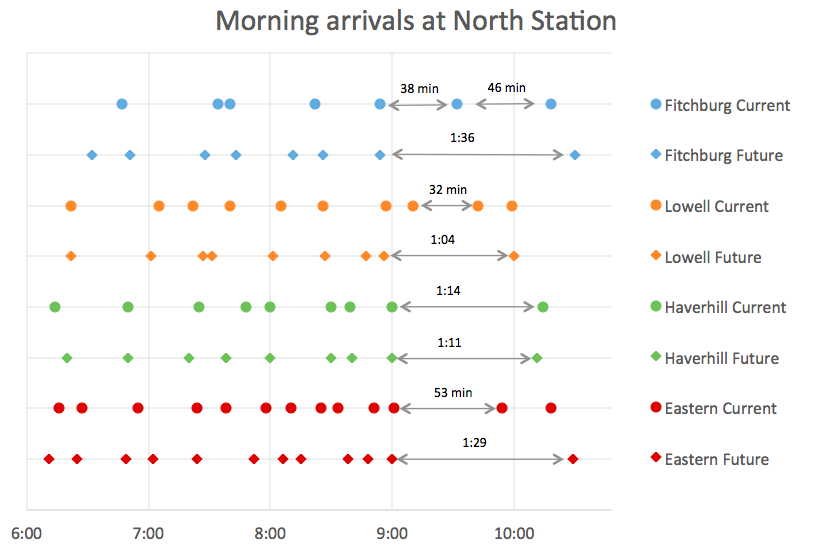

* Evenly Spaced Peak Service from Inner Core

Stations. No! Not only is this not attained, and do most inner core stations lose service, but some of the spacing gets much more uneven. For instance, service gaps at Swampscott go from 14-28-20-21-31-16-28-9 to 13-47-50-14-38-10. Currently, the range of gaps is 9 to 31 minutes; with the new schedule it ranges from 10 to 50!

The average time between departures goes from 25 to 35 minutes—a significant service cut, and the standard deviation in the gap goes from 13 minutes to 30! (If you include only arrivals at North Station before 9 a.m., the current average/stdev is 20/7, the future is 26/15. In no way is that evenly spaced.

Not only is this goal not attained, but it is downgraded significantly from current service. Again, they may have used computers, but lack some common sense.

* Optimized Peak Arrival and Departures from

North Station for Key Job Start and End Times. Key Job Start Times is completely undefined, but it seems to mean “everyone works 9-5.” This is not the case.

|

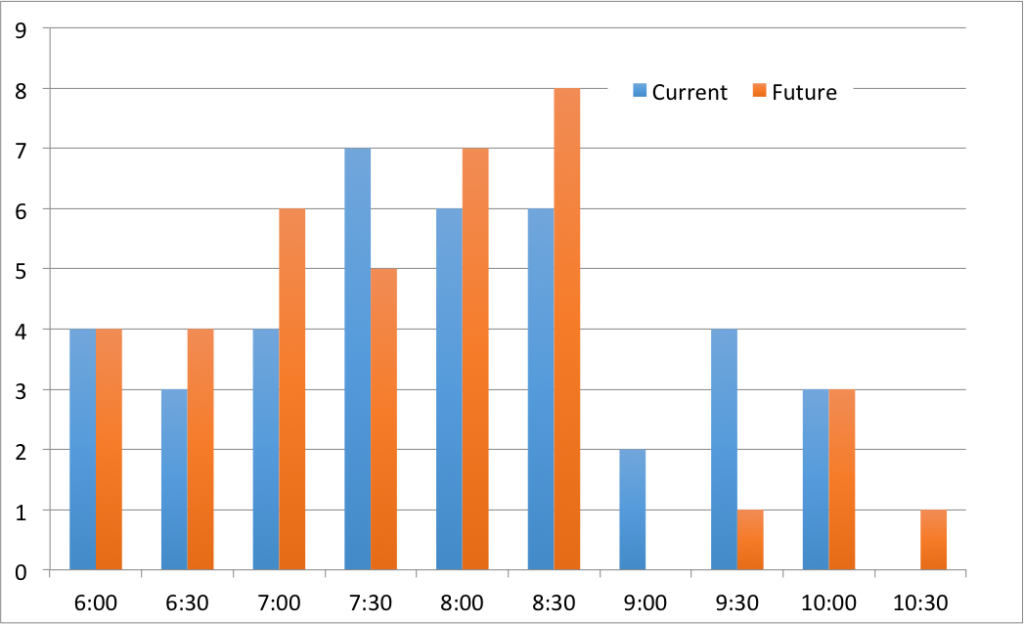

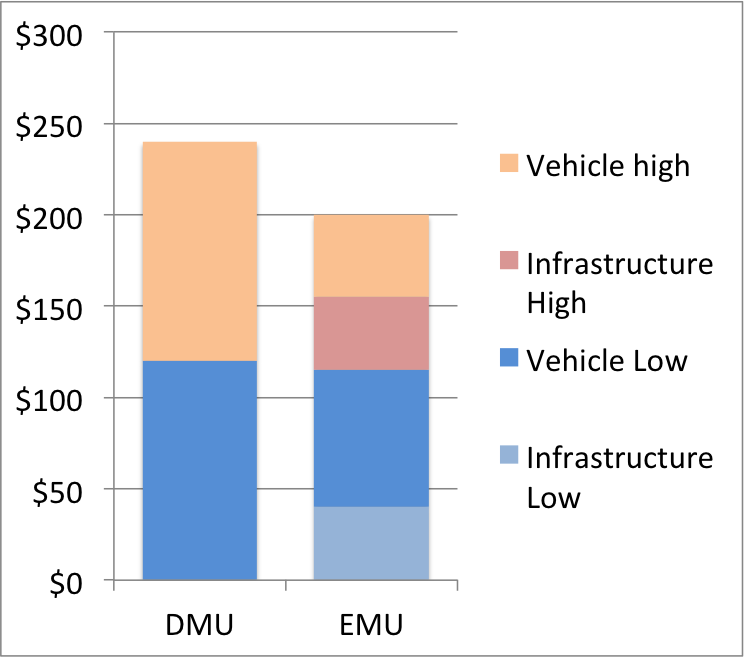

The T claims a goal is to reduce crowding.

But the new schedule has arrivals bunched at North Station. |

Efficient Train Movements at North Station to

Mitigate Crowding. Guess again. There are actually more concentrated arrivals and departures at North Station with the new schedule. This means more people crowding on to connecting services—the Green and Orange lines, and shuttles like EZRide—which are already at capacity.

* Standardized Peak “Box”: AM Peak North Station Arrival: 6:00 -9:00 PM Peak North Station Departure: 3:30 –

6:30. This is a solution looking for a problem. Passengers aren’t concerned about standardization of schedules between lines. They are concerned about having a train which serves their needs. And this doesn’t address the fact that the span of rush hour service, and the location of service gaps, is worse with the new schedule.

* Regular Off-Peak Departure Times. In general, this is attained.

Line-by-line, here are some

The Fitchburg Line (New Schedule Here)

Fitchburg wins. So do North Leominster, Shirley, Ayer, Littleton and South Acton. Beyond there …

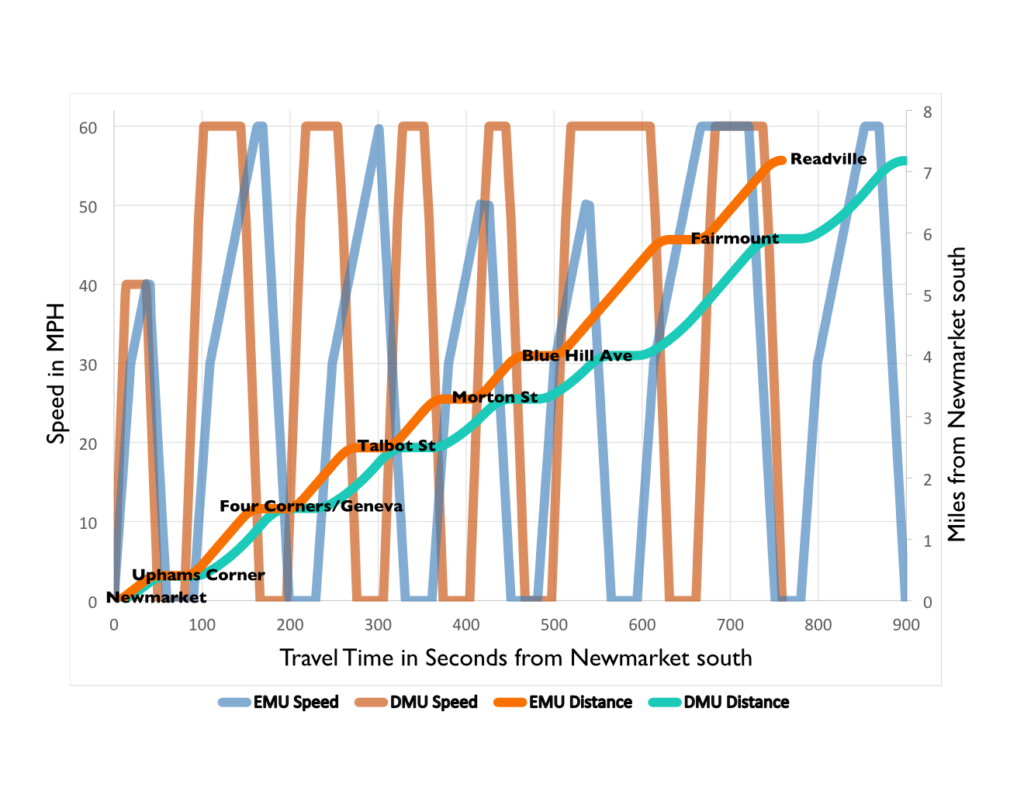

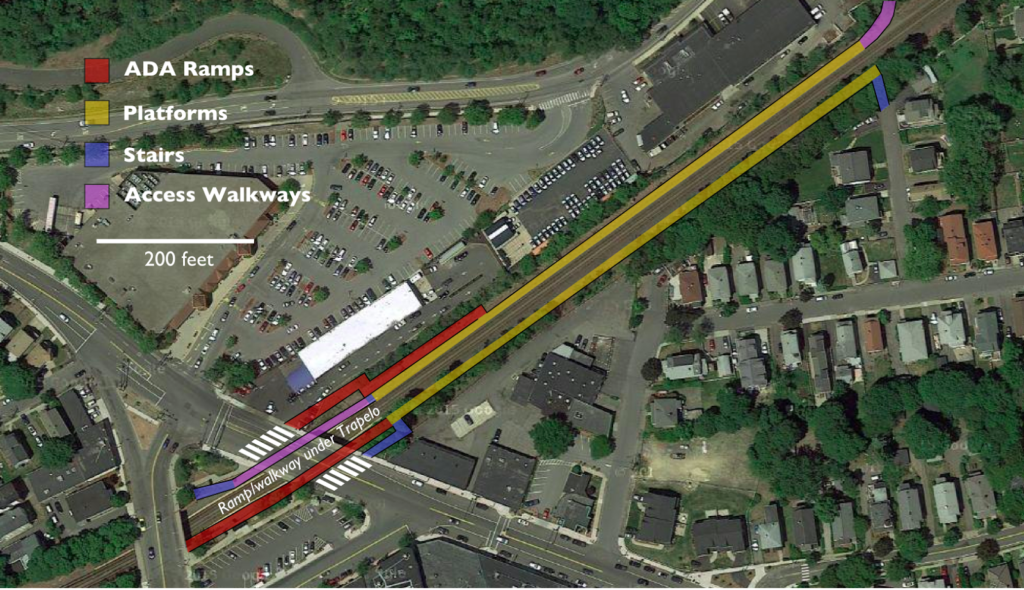

The Good. After investing a lot of money in the Fitchburg corridor in the past three years, cutting back weekend service during that time while the improvements were made. Now that it’s mostly finished, top speeds go from 60 to 80 mph, and with some high level platforms to speed boarding. The result? Travel times drop from 4 to 14 minutes, with the greater speeds on express trains. The fastest “super-express” that runs from Porter to South Acton drops from 32 to 24 minutes—a 25% improvement—giving that segment an average speed of 55 mph: the fastest single run of any train on the T’s Commuter Rail system. (Yes, even the Providence Line: the T refuses to spec equipment to run over 80 mph even though that line supports 125 mph.) There are more express trains, more local trains, and an earlier arrival at North Station. It’s a real win.

|

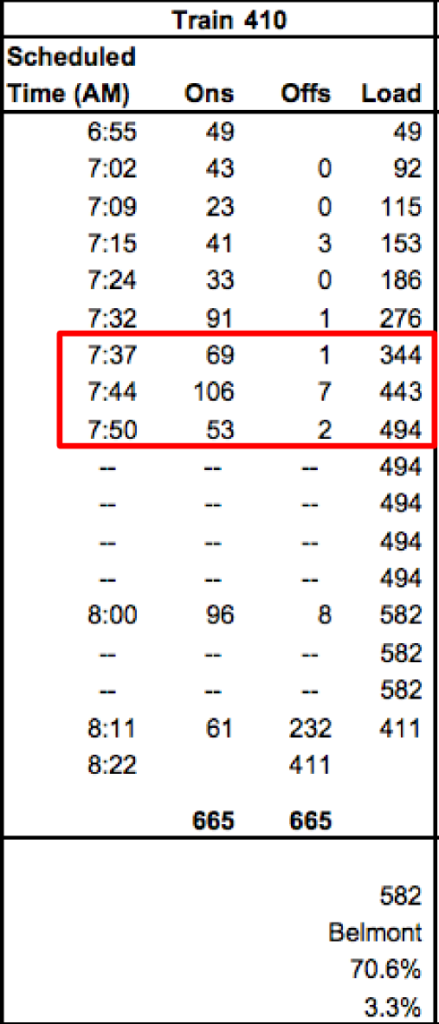

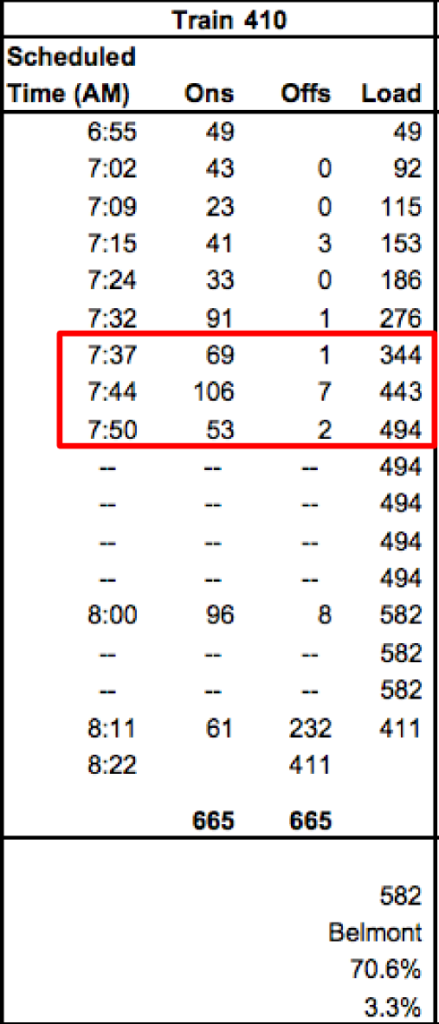

Train 410 boardings, 2012.

From here |

The Bad. The new express services are nice, but there are some issues. First, West Concord, Concord and Lincoln lose express service all together. This is a reduction in service for these communities, which will have fewer trains and longer trips. In addition, parking at South Acton is usually full before 7 a.m., so even though later express trains will stop there, they may have fewer riders as no one will be able to get to the station. Running the later express trains local to Lincoln would make too much sense, apparently, to help spread the ridership.

With the new track work, the schedules for these express trains will still be very competitive, but they’ll have more ridership. In the evening, one of the two express trains should have service added back at Lincoln and the Concord stations. Despite all the improvements, Concord, West Concord and Lincoln go from 5 departures to 4 in the morning. On train 410, Concord is the busiest stop, and more than 200 passengers board at these three stations (see right, from here). There is very little logic in cutting these stations. If anything, they should get a second express. How this counts as providing better service is questionable.

Weekend schedules get slightly better with all trains running to Fitchburg. But there are only trains every two-and-a-half hours, which, well, sucks. This kind of schedule means that the train is a mode of last resort on a weekend, and will attract few riders. This is an issue for the MBTA as a whole.

At some point, I’d heard that the plan was for the first train to arrive at Fitchburg before 8:00. 8:35 is certainly an improvement over the current 10 o’clock arrival, but could be earlier. The 45 minute headways the line currently has inbound between 7 and 9 p.m. shift to the 4 to 6 p.m. range, great for reverse commuters.

The new schedules should attract more commuters, especially to the express trains from Acton and Littleton. Driving Route 2 will never be time-competitive at rush hour with a 35 minute trip from South Acton to Boston. The issue there is that the parking lots have limited capacity and fill early. Increasing parking may be necessary, and in the longer range a station at West Acton would help spread the demand.

The Ugly. The last Fitchburg train leaves at 7:13—earlier than the current schedule—and there’s not another train until 9:00. The last rush hour train leaves Littleton at 7:51. In the current schedule, there’s another train at 8:58, but the new schedule has a gap until 9:35. So there’s no train in to North Station between 9 and 10 a.m. Want to drop the kids at school, grab a train at 8:30 and arrive downtown at 9:30? Tough luck. The T decided that rush hour trains should arrive between 6 and 9 a.m. and doesn’t seem to understand shoulder scheduling. Many other Commuter Rail schedules go from 30 minute rush hour to 60 minute midday headways (or longer) with a 45 minute headway in between. The same thing happens on either side of the evening rush. The T apparently doesn’t think that anyone works a non-9-to-5 schedule. If you want to grab a drink after work, you better grab two; you’ll be waiting a while.

There’s also the issue of what I call the “last trip fallacy.” Often the second-to-last service a route runs will be relatively busy, and people will see the last service as a safety net. So it appears that the final service doesn’t get high ridership, but it is the reason that the run before gets better ridership. If an agency cuts the final service—or in this case, creates a gap between the final rush hour train and the first evening train—people traveling at that time will simply abandon the system. There is no excuse for this type of poor service planning.

Suggestions:

* Push trains 410 and 492 back 10 to 20 minutes for a slightly later departure.

* In the evening, push train 421 back 15 or 20 minutes to better fill that service gap.

* Serve Lincoln, Concord and West Concord with trains 406, 410 and 417.

The Lowell Line (New Schedule Here)

The Lowell Line is currently the best-scheduled line the T runs. It has hourly, clockface schedules (which this page has long advocated for): show up midday at Winchester at 42 minutes past the hour and there’s a train to Boston. It’s what most other cities do, but the T can’t be bothered to run this sort of schedule on any other line. Lowell suffers from other issues, notably poor highway access to the Lowell and North Billerica park-and-ride lots (an extension to a park-and-ride lot at the New Hampshire border would be key—but should be paid for by New Hampshire), and a long gap between stations along the Billerica and Tewksbury Line.

But otherwise, this schedule is … ugly.

The Good. There’s not much improvement to report. I guess at least you don’t lose the hourly midday headways. That’s nice. And the bizarre and silly 322/216 pairing mid-afternoon goes away (two inbound trains ten minutes apart). Outbound service gains an express, and gets a nice gap-plugger 3 and 4 p.m.

The Bad. The weekend service. The T demonstrates five days per week that hourly service is feasible on the Lowell line, and that ridership supports it. Lowell, with the National Historic Park and Folk Festival, as well as a dense downtown, could easily support weekend headways. Yet it only sees a train every two hours.

In the morning, inbound service before 10 a.m. actually decreases significantly, from from 11 trains to 8! Neither of the Haverhill line trains stops at Wilmington or Anderson, reducing service on the inner part of the line. Right now, there are trains inbound from Anderson at 8:30, 8:45, 9:15 and 9:35. The new schedule has no train departing between 8:36 and 9:35. There’s plenty of room at the park-and-ride at Anderson, and today, if traffic on 93 is worse than usual, you don’t have to wait too long for the next train. With the new schedules? Good luck: miss 8:36 and you’re waiting an hour. The trains at 8:45 and 9:15 aren’t empty. Maybe both of those trains need not run, but a service around 9:00 seems like it would be necessary.

While the outer end of the line doesn’t lose service, the inner part gets killed. Winchester, Wedgemere and West Medford go from 9 trains arriving North Station before 10 a.m. to 6—a 33% service cut!

Outbound, the same issue arises: there’s no train between 6:25 and 7:25. Right now there is a train at 6:25, 6:55 and 7:30. The new schedule just kills off the 6:55 run. That’s just plain silly.

The Ugly. Let’s start with trains 304 and 306. Train 304 runs local out of Lowell at 6:40. Train 306 runs express ten minutes later and is scheduled in to North Station just four minutes after 304. Even without any issue on 304, this would mean that even without any delay, the express would be riding the local’s signals. This makes no sense. It could be easily solved in two separate ways: 1) Swap the local and express runs for 304 and 306. 2) Run 306 five minutes later, so that instead of a 10 minute gap and then a 24 minute gap, you get more even headways.

As commenter Tommy points out, the longest inbound gap in service at any time in the Lowell schedule is between—drumroll please—8:30 and 9:45 in the morning. Who goes to work between 8:30 and 9:45 in the morning? Anyone? Bueller? The answer is: more than 213 people from Winchester, Wedgmere and West Medford alone! The T touts “consistent, hourly local off-peak service” but doesn’t bother to provide this at the shoulder period of rush hour. Please.

Then there’s the Downeaster. The T claims they used computers to plan for constraints like Amtrak services. So then how would they explain the following:

* MBTA 337 departs North Station 6:00, arrives Anderson 6:25

* Amtrak 687 departs North Station 6:05, arrives Anderson 6:23

Now some of you may look at that and say “ooh! ooh! midline overtake!” Nope, there’s an inbound scheduled to leave Anderson at 6:05 and arrive North Station at 6:30. Sorry, guess again.

This is simply a glaring oversight. The T hired a contractor, ran a bunch of simulations, and completely borked Amtrak’s schedule. That’s just sloppy. Come on.

Suggestions:

Oh, boy, there are a lot here:

* Fix trains 304 and 306. This is not hard! Push 306 ten minutes later (it won’t affect the following Downeaster) to fill the gap.

* Stop each of the Wildcat trains at one of either Anderson or Wilmington, and maybe inner stations as well. Those trains aren’t full at Ballardvale, and the extra time to make one stop will not drastically affect the schedule (especially at Wilmington, where the line speed coming off of the Wildcat is 20 mph so the stop penalty is minimal). In the long run, running more trains via Wildcat and having skip-stop service on the inner part of the line would make a lot of sense; this can be a separate post all together.

* Push train 312 back to at least 8:25, its current departure time. Run it local; the two Haverhill Line trains will provide express service to Anderson and Wilmington.

* Good god, fix the Downeaster conflict. That’s just painful.

* And run service between 6:25 and 7:30. Reinstating the 6:55 Wildcat train would make a lot of sense.

The Haverhill Line (New Schedule Here)

The Good: Line speeds get faster; train schedules improve by 5 to 6 minutes for many trains. That’s good, and might mean that some trains running ahead of schedule will no longer have to wait a couple of minutes to maintain schedules. Train 206 will run from Haverhill to Boston in 58 minutes via the Wildcat Line, which is really quite good, although some of this time is saved with an express run in on the Lowell Line; this will result in a reduction in service on the Lowell Line. Another change is that midday short-turns are mostly eliminated, including the Anderson turn (which then ran duplicative service via the Wildcat), with more full-line service. This is good.

The Bad: Same as above. No trains inbound between 9 and 10, but that’s actually the current case for this line. And since this schedule is only being tweaked, it might be better planned when it’s complete.

But for some outbound trains, there’s some weirdness. Right now, there are outbound trains at 2:20, 3:10, 3:50 and 4:30. The new schedule has a big gap between 2:00 and 3:30 for the outer stations (vial the Wildcat Branch) and until 3:45 for the inner local. The 5:15 express, which currently makes its first stop in Wakefield, now will skip Wakefield—the third busiest stop on the line—but won’t save any time. This stop should be added back in. (More than 1000 people—more ridership than the Wakefield station!—have signed a petition calling for just this.)

The Ugly. Like other lines, there’s a big gap—70 minutes—after 6:30. The current schedule then has an 8:40 train; that disappears. So there’s a two-hour gap in the early evening where there wasn’t one before. This could adversely affect ridership in this area.

We’ll see if they can further disrupt the line once the bridge maintenance in Haverhill is done.

Suggestions:

* See if there is a way to account for the long service gap between the 2:00 departure an the first evening departures at 3:30 and 3:45. Maybe running the 3:30 as a local train would free up the other set to run another local run earlier in the afternoon (or reinstate the 6:55).

* Add Wakefield back in to the afternoon express run.

* Add some stops to Wildcat trains (see Lowell Line)

* Add service back to the evening schedule, which loses service with the new schedules.

The Newburyport/Rockport Line (New Schedule Here)

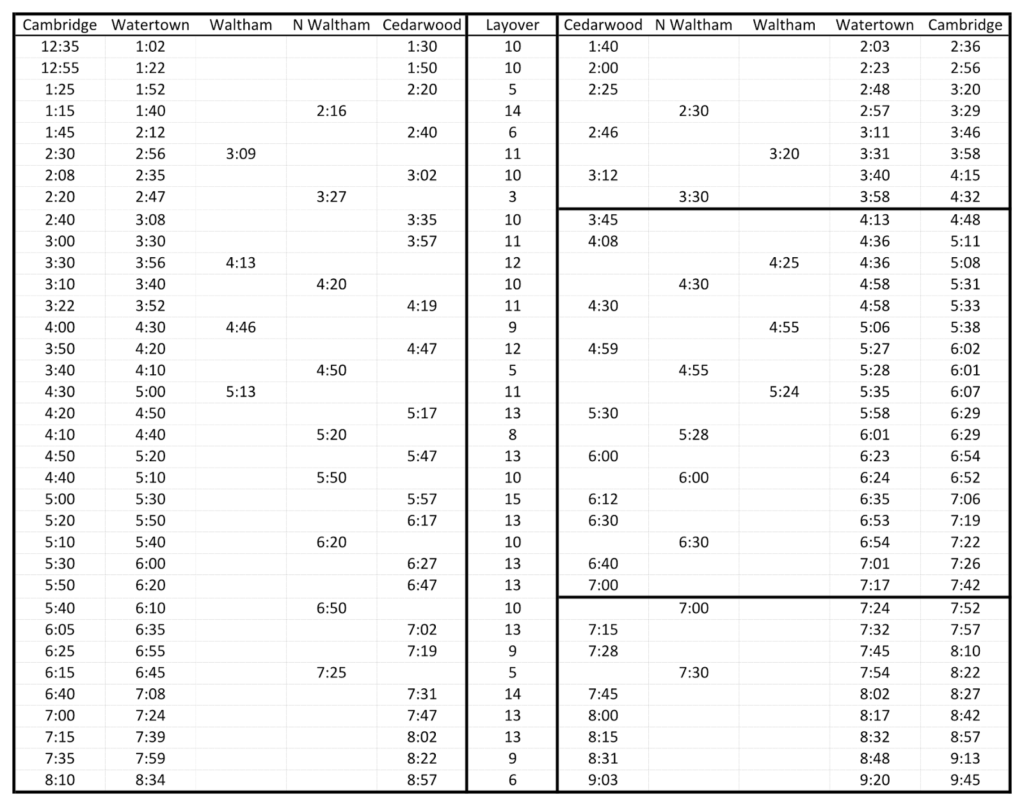

The Good: Newburyport gets some express trains. They haven’t had those in a long time (maybe not since the ’60s). Rockport loses some express trains but gets a later morning departure—currently the last train inbound on the Rockport branch departs at 7:22; the new latest train leaves 28 minutes later. That’s good! Newburyport’s last train gets a little earlier; 7:42 instead of 7:55.

Afternoon reverse-peak service on the Newburyport line is improved dramatically, with three inbound rush hour departures, no three-plus hour service gap after 5:55, and hourly departures all evening. This serves Ebsco Publishing, which has several dozen Commuter Rail riders from Boston and the North Shore owing to a generous transit benefit, limited on-site parking and a short walk from the station to the office.

The Bad: Service on this line is squeezed dramatically, and stops closer to the city lose service.

There is significant reverse-peak ridership on this line to Ipswich, where Ebsco Publishing has a parking crunch and transit benefit. Yet there’s no outbound service between 7:15 and 9:00. The new schedule doesn’t address this, but it could, and improve late-morning commute times as well:

The 7:05 Beverly turn train could be extended to Newburyport. This would give Newburyport a later departure in the range of 8:05, with an Ipswich arrival of 7:45. It could then depart at 8:20, depart Salem around 8:50, and arrive at 9:20. What happens to the current short turn? There are trains inbound from Beverly at 7:53, 8:00 and 8:10. The middle train is the current turn. An extra car on the 7:53 and 8:10 would take the necessary capacity. We don’t need Orange Line-level headways on the inner part of the Eastern Route, at least not at the expense of later service.

There’s also the question of why there is a 50-minute gap between Rockport service during the height of evening rush, and two Newburyport trains running 20 minutes apart. These could be better scheduled. And the current Salem transfer for the 6:45 evening train—which allows it to serve both lines—is gone. This is a good idea poorly executed: there is really no explanation why the transfer should take 23 minutes. Other Commuter Rail systems with transfers are able to run them much more quickly; the transfer train could sit north of Salem, wait for 171 to pull out, get backed in by the conductor, load, and leave 5 or 10—at most—minutes later. But instead of fixing this, it is axed. Great. (This would be a good place for DMU service, allowing one train to run the trunk route from North Station to Salem and set of DMUs to pick up one of the branches, especially for non-rush service.)

And for Swampscott, Lynn and Chelsea? Sorry, guys, you lose two trains per rush hour, and while you currently have service every 30 minutes or better, get ready for some 50 minute service gaps.

The Ugly:

Train 120. Express from Rockport to North Station. I just can’t even. I don’t have words. It makes my eyes bleed. This introduces a three hour gap for the reverse commute from Gloucester inbound. This is insane. People use these trains. I’ve been on these trains. They’re not full, but they serve the general public. Run this train with stops. If it means that some trains in the 6:00 range are run a bit later, that’s probably good. Just make the goddamn stops. This schedule is just stupid.

The huge gaps in late rush hour service both morning and evening is also so bad it belongs in Ugly, not just Bad. There are six trains scheduled in to North Station between 8:06 and 9:00—that’s one every 9 minutes. Then there’s a 90 minute service gap. Do you run the Red Line every four minutes at rush hour and then have a 40 minute service gap? No! Don’t do that here.

The current schedule, while not much better, has six trains in 1:06, and then a 54 minute gap. We’re taking something that is a problem, and making it worse. This is asinine. The above schedule change, which would enhance reverse-peak service, would also plug this hole quite nicely, with a catch-all train leaving Beverly and Salem around 8:50, and arriving in Boston around 9:20. Subway-level service is great, but it should not come at the expense of shoulder-peak times.

The afternoon is similar. Currently, the 6:45 departure from North Station carries more than 400 passengers, and it is unceremoniously brought out back and shot. There are trains leaving North Station at 6:10, 6:20 and 6:30, and then nothing until 7:45. Just pushing each of these trains back by a few minutes—departing 6:10, 6:30 and 6:50—would make a huge difference. If one of these is the turn of 120, then the extra time will give it sufficient time to make inbound stops.

Suggestions:

* Train 120. Fix it. It should make inbound stops. Otherwise it’s a brutal waste of public funds, running a revenue train with maybe half a dozen passengers and creating a three-hour service gap.

* Fix the service gaps in the later morning and later evening rush periods. Two plans to do so are outlined above.

* A train every 9 minutes is nice, but with any hiccough will cause cascading service issues. Better to have a train every 15 minutes, and get rid of the 90 minute later-morning gap.

* Look in to an improved Salem transfer for a later PM rush hour train.