Over several years, a median has been proposed on Snelling Avenue in Saint Paul, to calm traffic and aide pedestrians. A long saga may soon be coming to fruition, although the local city councilmember is holding up the process. In several parts, here is the story.

A. An anecdote

B. Background and history

C. Current conditions

D. Crossing the street

E. The Grand Avenue median

F. Bring the median to Snelling

G. Project status.

Snelling and Grand, the north end of the proposed median.

Snelling and Grand, the north end of the proposed median.

A. An anecdote

Last August, I walked from my house two blocks east, planning to attend the opening of a new athletic facility at my alma mater. There is one barrier between my house and the college, a quarter of a mile west: Snelling Avenue.

I walked down to Snelling, and—well—I’ll let my archived chat (cleaned up a bit) from that evening tell the story:

… I got to Snelling, which is four lanes wide and I did my usual walk out in the crosswalk and start waving my arms and pointing at the crosswalk as the idiotic traffic goes by completely neglecting crosswalks (I swear people are worse about stopping at crosswalks here than in Boston).

Finally, a guy in a minivan in the nearest lane stops and I slowly walk out in front of him as he glares at me. Then the car in the next lane slows down, honks at me, and speeds up.

I cross behind it and go on my way, but these cars aren’t done. The guy in the van flips me off, and then goes to bang an U-ey to come back and yell at me (Minnesotans bottle up their anger and let it out when they are driving.)—Except, the other car was in his blind spot, so he turned RIGHT IN TO IT!

No one was hurt, but the drivers were mad at me (even though the accident happened 100 feet down the road from the crosswalk). The woman in the car ran across four lanes of traffic—not in a crosswalk, mind you— and started screaming at me. I told her that it was a crosswalk and I had right of way.

Her response: “But it’s rush hour. You can’t go walking across busy streets at Rush Hour” and then claims that her mother, who was driving, is from Arizona, where the laws are different (they aren’t). The other guy also told me that, sure, maybe there is a law about pedestrians having the right of way, but it’s rush hour—they had conferred and this was their best defense. Obviously it is okay to break the law at certain times of day. (“I’m sorry officer, but I’m allowed to carry around half a kilo of cocaine at night, right?”)

The woman wanted me to stay until the cops came so they could give me a ticket … I said I highly doubted that I’d get a ticket. The cop came, and they rushed up to him. “And a pedestrian—” they stammered, but he cut them off.

“Someone was struck? Where are they.”

“I’m right here, officer, I’m fine,” I said. He sort of told them to go away and then told me that I certainly do have the right of way, rush hour or not.

The Goodrich crosswalk where the above incident was triggered. The cars actually collided about 100 feet to the north (right) of this picture.

The Goodrich crosswalk where the above incident was triggered. The cars actually collided about 100 feet to the north (right) of this picture.

B. Background and history

Snelling Avenue is a main north-south road in Saint Paul, and lies about three miles west of Downtown and a mile and a half east of the Mississippi, running down the center of a lobe of land around which the river curves. It was undeveloped until the early 1900s when several streetcar lines running from downtown ran west, and one of two “crosstown” lines (the other being on Lake Street in Minneapolis) was built on Snelling. Because of its location and streetcar history, it was built relatively wide—sixty to seventy-five feet—for its entire length from Ford Parkway to Como Avenue, plus parking in most areas. When the streetcar tracks came out, Snelling became a major north-south artery—it is designated as Minnesota State Highway 51—and given four lanes of traffic plus parking.

However, it was never designed to be a freeway and serves neighborhoods which, despite the Twin Cities’ reliance on the automobile, are still rather walkable. Nearly all of the construction along and near Snelling is pre-war, and most of it is still in existence. The avenue itself is lined with a mixture of single- and multi-family housing, a few apartment blocks and commercial development. While a few sections have been given over to surface parking and strip malls, most development is still built flush with the sidewalk, and the majority of the storefronts date from the 1920s or before, often with housing above. The route is still served by a bus line, the 84, which is designated as a “high frequency route” and has 15-minute headways every day but Sunday.

Still, despite the development along the street, the wide, straight nature gives it a resemblance to many of the four lane “streets” which grace the suburbs and have 45 or 50 mph speed limits. And, for a variety of reasons, it receives quite a bit of traffic which ostensibly does not orignate or terminate along the street. The local neighborhoods have, thus far, been successful in keeping Ayd Mill Road (I will, in the future, post about Ayd Mill) from being completed to connect Interstates 35E and 94, so quite a bit of traffic crossing the Mississippi on 35E chooses Snelling to travel north to the Midway and I-94. In addition, since I-35E is not open to trucks north of the river, many big rigs use Snelling to go north. And because these drivers often have navigated wide, fast roads they often don’t heed the 30 mph speed limit on Snelling. Enforcement is relatively good—more often than not a patrol car sits at the end of Goodrich Avenue, midway between Saint Clair and Grand Avenues, looking for speeders (although not drivers failing to yield right-of-way, it seems), and usually does not have to wait long. Still, traffic, especially at rush hour, is rather frenetic.

C. Current conditions

Between Saint Clair and Summit Avenues, Snelling is bounded on the west by Macalester College. From Saint Clair to Grand, about 0.4 miles, there are no lights and no cross-streets—all of the streets end at Snelling. Thus, along this section of road, there is little to keep traffic from moving slowly. The college generally opens away from Snelling on to quads, and while the street is well-landscaped, there are not uses which interact with the street. On the east side of the street, it is generally bounded by houses which face on to the cross-streets. It feels like a road that should have a faster speed limit than 30.

However, it is highly trafficked by pedestrians as well as cars. It carries the aforementioned 84 bus route plus an express route at rush hours to Minneapolis (the 144). And while most Macalester freshmen and sophomores do live in on-campus dorms, most upperclassmen do not. During the school year, there is a steady stream of pedestrian traffic from rental properties in the neighborhood to the east to the college and back, several times a day. None of this is a problem—the college interacts surprisingly well with the neighborhood (there are isolated incidents, and some resentment of student housing causing the decay of some property, but real estate values are quite high in the area). Added together, there are thousands of trips across Snelling every day in addition to the thousands of trips along the street.

D. Crossing the street

The crosswalk south of Lincoln

Herein lies the problem: it’s not easy to cross the street. Often at crosswalks, both marked and unmarked, one lane of traffic will stop for a pedestrian. However, walking in front of a stopped vehicle is nothing short of a death wish: traffic often passes stopped cars oblivious to pedestrians and statute at speed, making it absolutely necessary for pedestrians to check other lanes when crossing. With four lanes of traffic, waiting for traffic to stop in all lanes is often a cumbersome task, leading to irritation of both the crossing party and law-abiding motorists who have to wait for their less-lawful peers.

And then, as illustrated by the anecdote at the top of this post, there are those motorists who believe that they are somehow exempt from the law, and don’t find it necessary to look for or stop for motorists. While no one, to my knowledge, has been seriously injured or killed crossing Snelling, it is a proverbial accident waiting to happen. And a couple of motorists this past summer had some time with their cars in the shop because of their failure to obey the law. Perhaps, during that time, they had to walk as well.

E. The Grand Avenue median

Just west of Snelling, Grand Avenue bisects the Macalester College campus. Originally, Grand terminated at the campus, which ran north to Summit, but was extended west in 1890 to accommodate the streetcars. Grand is one of the major commercial corridors in Saint Paul, and both east and west of the college are blocks of stores. Grand is slightly wider than most of the east-west streetcar streets in Saint Paul (Randolph, Saint Clair, Selby, Minnehaha) and today sports, along most of its length, two lanes of traffic, a turn lane (despite the general absence of driveways along the street) and parking on both sides. Through the college, however, the parking lanes were eliminated and the turn lane became a striped median. Traffic didn’t zoom through campus, with a traffic light at the east end and a commercial corridor to the west, but was still able to make some speed through the campus without parked cars or storefronts.

The Grand Avenue median. Much nicer than yellow striping on asphalt.

The Grand Avenue median. Much nicer than yellow striping on asphalt.

The issue was less the traffic and more the fact that this portion of Grand Avenue divides the academic buildings and dining hall at Macalester from most of the housing. Thus, approximately 1000 students daily cross Grand for classes, meals and to go to the library. On any given day are likely more feet than tires on the avenue. And for decades, the students generally crossed the street at three intersecting sidewalks between Snelling and Macalester avenues. The median was first proposed in the fall of 2002, at a time when students periodically painted crosswalks across the street, which would then be blacked out by police. (Despite current signs which state that pedestrians do not have the right of way, the crossings would appear to be “unmarked crosswalks,” extensions of sidewalks across the roadway.)

The spring of 2003 brought the beginning of experimentation, with a chain-link fence erected in order to funnel students to one crossing, but the fence was taken down repeatedly by students (not that I know any of the culprits or anything). Subsequent surveys showed that students felt safer crossing in the temporary medians which were erected. Designs changed over the next few years; parking spaces which had been planned were eliminated, and the communited supported the median as well. It was erected in late 2004 and has beautified the street, created a better environment for pedestrians and not had any major ill effects.

F. Bringing a median to Snelling

View this map larger in a new window

Map of the area of the Snelling median

The median on Grand was not very controversial. The only abutter was the college, the center of the street was already striped as a median, and no businesses were impacted. The college footed most of the construction bill and the street is safer today for all. On Snelling, the median would be quite a bit longer and involve dozen of abutters and several cross streets. Furthermore, since Snelling is a state highway, the Minnesota Department of Transportation is involved. In other words, there is a much greater opportunity for dissent.

The median is being spearheaded by the Macalester High Winds Fund, Macalester’s community liason and real estate management. The Mac-Groveland community has also been heavily involved in the process. The community has generally been in favor, but not completely. The pros are generally rather obvious (calmer traffic, easier crossings, &c.) but the cons are a bit harder to figure, but still somewhat important to examine. According to several articles, they break down to:

• The potential loss of parking, especially near Grand and the new athletic facility

• Increased congestion related to slower traffic

• The elimination of left-turning traffic on to two streets (Sargent, Fairmont, Lincoln is currently one way and on to which turns are not allowed), and the subsequent addition of traffic to some streets (Goodrich and Osceola)

• Loss of access to some businesses, notably Lincoln Commons between Lincoln and Grand

• Narrower areas for bikers

• No pull-offs for buses

There are other concerns, but these are the most well-founded—the others are raised by citizens going on about the spoiled brats who dare to cross Snelling or residents who refer to Snelling as a highway (which it, historically, is not).

First, parking. Parking is a very frequent planning concern and probably one of the most unheralded (since it is not at all “sexy”), even in neighborhoods such as Mac-Groveland where parking is ample and generally free. Along Snelling, there are three distinct parking issues. The first is near Saint Clair. Here, some street parking would disappear, but its impact would be minimal. The stores along Snelling north of Saint Clair have parking behind, and on the west side the street borders the Macalester stadium, which is rarely a driver of major traffic. During events which do create traffic, the street parking fills rather quickly and then spills on to neighboring streets, but, again, this does not occur frequently.

Between Sargent and Lincoln, parking is rarely an issue. On the west side of the street, it is bordered by college buildings which do not drive huge amounts of traffic or, if they do, provide ample parking. The on-street spaces which might be eliminated are already minimized by bus stops and loading zones, so at most a few cars would spill on to the east-west streets, which, except during events at the athletic facility, have ample parking. The new athletic facility lots provide more parking than the ones which were replaced, even though it serves the same sized community. Except during events, it is rarely full. The church across the street has a large parking lot which is also underutilized.

The main concern is north of Lincoln. Here, street parking is rather heavily used for local businesses, especially at the end of rush hour. While businesses do provide their own parking (Lincoln Commons is a very small strip-mall) it is sometimes not adequate in the evening. However, the number of street spots available is minimal. North of Lincoln Commons is a bus stop and turn lane, and parking is prohibited. South of it, there are several driveways which preclude parking. Five spots, at most, would be eliminated which directly serve these businesses, and the lack of these spaces may ease congestion entering and exiting the lot.

This segues well in to the next issue: the elimination of left turns in to Lincoln Commons. Lincoln Commons is a four-store (a Kinkos-Fedex, a coffee shop, a hair salon and a fish store) urban-strip mall development. Unlike some parts of Snelling (notably the Cheapo Discs north of Summit, which has a parking lot far larger than necessitated) it is not set back far from the street and the parking is minimal and well-landscaped. Lincoln Commons is on the west side of the avenue, and while Lincoln Avenue, at the south end of the block, is one-way towards Snelling, Lincoln can be entered and exited to the southbound side of Snelling. There is a minimal turn lane from these lanes, which allows traffic to access the complex without tying up Snelling while waiting for the northbound lanes to clear. However, the rigmarole to access the complex seems quite dangerous—sitting in the middle of a busy street with cars passing by on both sides in opposite directions. In fact, it does not meet current safety protocols and would likely be eliminated by the Department of Transportation in upcoming years. It is also not particularly pedestrian-friendly, with traffic turning from thirty or forty feet and often gunning across the sidewalk in an attempt to clear small breaks in traffic.

The left turn “lane” in to Lincoln Commons.

The left turn “lane” in to Lincoln Commons.

The proposed median would cut off the southbound lanes of Snelling from Lincoln Commons, meaning that it could only be accessed and enterd from the northbound lanes. The concern amongst the businesses is that this will necessitate a longer procedure for southbound customers. Instead of a left in to the parking lot and a left out, they’ll be forced to make a U-turn in to the northbound lanes, a right turn in to the lot, a right out of it, and another U-turn at Grand, or a combination of turns to return to Snelling southbound. These will add time, but they will also require much less risky maneuvers, namely nixing the double mid-block left turns across the Northbound lanes of Snelling. It will help pedestrians as well, as cars will only come from one direction, and won’t have to worry about opposing traffic and pedestrians. It is not a perfect situation—it will probably have a minor effect on these businesses (especially the fish store, which is often visited by commuters for a short time to pick up dinner during evening rush hour)—but also not one which will effect the businesses to the extent that they will see a major negative impact in sales.

In fact, in the long term, it may help. If the neighborhood is more walkable—that is, if Snelling is no longer perceived as a barrier—they will expand their market for customers who do not drive. In fact, if the procedure for parking involves four moves (U-turn, right turn, right turn, U-turn) instead of two, it may entice some local residents to walk or bike, rather than driving. Consider, for instance, two potential markets. The first lives several minutes drive from Lincoln Commons, or pass the complex as part of a longer commute. They are coming to the stores there for a specific service they can not find closer to home, and driving is likely their only means of transportation. For these customers, the median may add one minute to a fifteen minute trip, an insignificant change. They’ll still come, and they’ll still drive.

The other market is made up of nearby residents, who may live only two or three minutes’ drive away, comparable to a walk of five or ten minutes. Most notably, I am thinking of residents who live west of Macalester. For these customers, adding a minute to their drive time would be an increase of 20-25%, making it significantly longer. However, their walking time would remain the same, and may even be shorter, and certainly more pleasant. For this customer base, the complex would be further in terms of driving time, but perhaps closer overall. And pedestrians do not require parking spaces.

There is also the concern that eliminating left turns on to and off of some streets will result in an increase in traffic on others. This is not a major issue because these streets only serve the immediate neighborhoods—all through traffic follows Grand or Saint Clair which lack stop signs. Traffic on these streets is quite minimal, with no more than a few dozen cars each hour. Doubling the traffic on any street would not be noticeable—they’d still be quiet, residential streets. In addition, with some turns blocked off, traffic would be more likely to utilize the north-south streets to access Grand and Saint Clair, and subsequently Snelling. Traffic patterns will change, and traffic may become more concentrated, but the number of cars involved are low enough that it will be a nonissue.

The Snelling “raceway.” Note the lack of any parking lane markings, making the street seem even wider than it is.

The Snelling “raceway.” Note the lack of any parking lane markings, making the street seem even wider than it is.

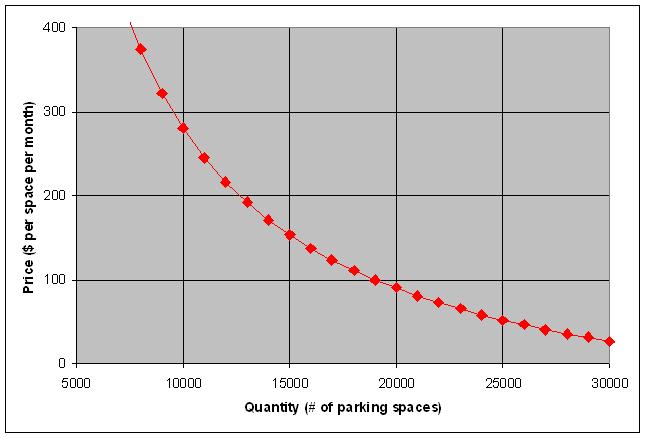

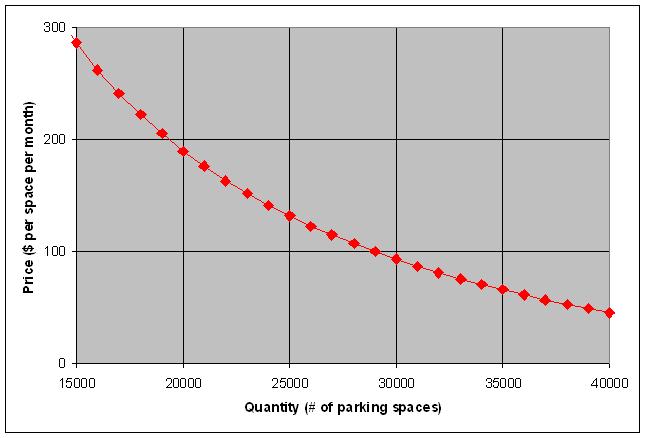

The next issue, congestion related to slower traffic is, in my opinion, a very minor concern. The main issue with more congestion is for those who consider Snelling to be a trunk highway. It is not. It is a city street, and for a variety of reasons, has a lot of traffic. Still, it is not congested. Traffic counts on the street are approximately 25,000 per day, which is not particularly high for a four-lane road. It is rare for traffic to have to sit at lights for more than one light cycle, and between intersections, traffic moves too quickly if anything. If anything, traffic calming would ease congestion. Instead of jackrabbit starts and braking for red lights from 40 mph to zero, it would allow for smoother traffic flow. The amount of congestion on such a street is not dictated by the speed of the traffic, but by traffic lights and turning vehicles. Reducing turns would do far more to ease congestion than reducing speed would to create it.

The median will mainly change conditions for motorists and pedestrians, but will also effect cyclists and transit riders. There is some concern that the narrowing of the street from five lanes (or even seven, if the parking lanes are included) to four will create a hardship for bikers, who will no longer have a wide, and often empty, parking lane in which to seek refuge. There are two reasons why the new design may actually benefit cyclists. The first is that it will better define the uses of the street, on which there is currently no delineation be the travel lanes and parking lanes. While bike lanes are not in the current design, it is possible they could be demarcated at a later date. The second is that biking on Snelling is currently rather horrid. If the avenue becomes more like Lexington Parkway, the north-south street a mile east, it will be superior to the current conditions.

Finally, the buses which ply Snelling four (or more) times per hour will no longer have stops in which to pull off at minor cross streets. This, too, is a minor issue. First of all, most bus ridership is concentrated at Grand and Saint Clair, where there are bus shelters and benches, as opposed to signposts. So buses usually stop for only a few seconds. Secondly, buses waste quite a bit of time pulling off the travel lane to pick up passengers and then having to attempt to merge back in, where drivers only sometimes yield right of way. And since Snelling will still have multiple lanes in each direction, traffic will be able to pass buses if they need to stop for longer periods of time.

G. Project status

The High Winds Fund at Macalester has been instrumental in securing funds for the Snelling median, which has received the approval of the neighborhood council as well. In addition to state funding, an appropriation of $475,000 was received from Congress, since it was federal legislation which made Snelling the de facto route for truck which might otherwise use I-35E. However, to received the state funds, and probably the federal funding, the project must start by June 30.

The ducks are all in line, except for one: The local councilmember, Pat Harris, has long been opposed to the project. The Lincoln Commons landlord has been unhappy about the perceived lack of business (which, as discussed, may not even be the case) and wanted the median to start south of his complex—negating the effect of the median where the plurality of accidents have occurred, and cutting off the possibility of state money. It will come down to a few days and community participation as to whether the median will come to fruition—or get caught up in local politics. If it does, it will be to the detriment of thousands of pedestrians in a supposedly walkable neighborhood.

Finally, like it or not, this is a shovel-ready stimulus project. Assuming we can agree that on its merits it is at least palatable, it will bring in jobs to the community. Can we afford not to do something like that?