The worst traffic in New England is on I-93, going north and south into and out of Boston. When highways were canceled in 1970s and money put towards transit, I-93 was left doing the duty of two highways south of the city (since the Southwest Corridor was nixed) and four to the north (where Routes 2 and 3 were meant to access the city via Cambridge, and Route 95 was to be routed over the Northeast Expressway). The phrase that comes to mind is “three quarts of [something] in to a two quart pail.” There is simply not the roadway capacity to handle the traffic on this road in the morning or evening, there are choke points at other interchanges, and as a result traffic is backed up for several hours each morning and evening, turning a 60 minute drive from Manchester to Boston in to a two- to three-hour ordeal.

The corridor from Concord, N.H. to Boston has frequent bus service, but these buses sit in the same traffic as everybody else until a short carpool lane just to the north of Boston. There is no rail service beyond Lawrence and Lowell, meaning that alternatives to driving require many motorists to travel I-93 to some extent. New Hampshire is spending $800 million to widen its section of the road, and is leaving space for future rail transit and building bus park-and-ride facilities. However, under the previous Republican administration, the state refused to study rail transit service. That vote was reversed recently, and New Hampshire will commission a study of rail service north of the border. *

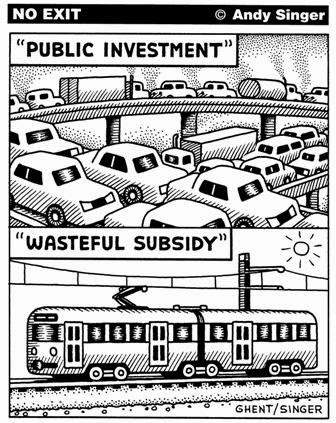

As usual, opponents come out of the woodwork whenever transportation dollars are slated to be spent on anything other than King Car. “Where are you going to find a few million dollars?” they exclaim, “When you just spent a billion on widening a roadway!” It’s a waste of taxpayer dollars! A boondoggle! It will never pay for itself!

Tell me, again, who is paying the billion dollars to widen 93? Oh, wait, that is a necessary public investment.

There are several salient issues here:

- Widening the roadway in New Hampshire makes some empirical sense, and going northbound will eliminate a traffic-knotting lane drop at the border. However, the bigger issues have to do with infrastructure further south in Massachusetts not being able to handle more cars from the north. So widening the roadway will not aid many travelers, and may in fact make overall traffic worse where people want to go.

- I-93 would be a good candidate for a proper HOV, or perhaps HOV/Toll lane, which would aid bus traffic and encourage carpooling, and given the number of buses on I-93 would benefit a high number of road users.

- In regards to rail, and to echo a frequent sentiment at the California High Speed Rail Blog, the cost of doing nothing is not zero. In other words, if there are no changes made to transportation between New Hampshire and Boston, there are significant costs which New Hampshire will incur. We’ve already seen that the cost of widening I-93 in New Hampshire is nearly $1 billion. What are the costs of poor access to the Boston job market for New Hampshire residents? Of lower property values because of decreased demand due to this limited access? Of time spent in cars in traffic for hours per day? Of tourists who don’t take a weekend trip because of traffic on Friday evening?

First, how widening in New Hampshire doesn’t help traffic down south, or the three quarts in a two quart pail issue. New Hampshire can widen I-93 within its borders all it wants, but driving solely I-93 in New Hampshire gets you from nowhere to nowhere. No offense meant—there are not the major, growing job centers in Southern New Hampshire as there are in Massachusetts. Much of the traffic on I-93 is destined for offices along 495 and 128 in the Bay State, or further south in Boston. Adding space on this section of I-93 will ease some congestion in the state, but it will only lead to more cars traveling southwards in to an existing wall of traffic. The utility of the road for everyone, but especially for New Hampshire commuters, is not enhanced by this project.

Every morning, from 6 a.m. until 9, 10 or even 11, traffic on I-93 grinds to a halt. It first slows in Lawrence, where traffic backing up off of I-495 can slow the commute. Even as the roadway widens from three lanes to four, traffic slows south of 495 as it approaches the wholly inadequate interchange at 128, where traffic backs up off the mainline and through the tight cloverleaf. From there, traffic sometimes eases through the Middlesex Fells, but the roadway then narrows from four lanes to three, one of which is a carpool-only lane. Although traffic no longer backs up off of the Central Artery (which cost, ahem,

$15 billion to replace), it’s sufficiently squeezed down that there are only so many cars which can find their way in to the downtown tunnel. Mitigating the 128 interchange is no easy task and will probably cost on the order of

$200 million or more. Adding capacity to the roadway through Somerville is a non-starter, and this squeeze will probably never be expanded.

There is a way to increase the utility of the highway without widening it, which is to change the demand model for the roadway by

introducing an HOV facility. Right now, there is a 2.5 mile long carpool lane on the southbound side of the roadway from

Medford to Boston. This saves carpoolers, and buses, a few minutes on their morning commute, since the lane starts before the Somerville lane drop. However, it is otherwise inadequate in several manners. It provides no access to the Storrow Drive off ramp, which serves major employment centers in Boston and Cambridge. It also reintegrates traffic on to the Central Artery where it has to merge across several lanes to exit. Most importantly, however, it starts far too far south, and during peak hours the traffic jam starts far before the lane becomes available. Oh, right: there’s no HOV lane going northbound.

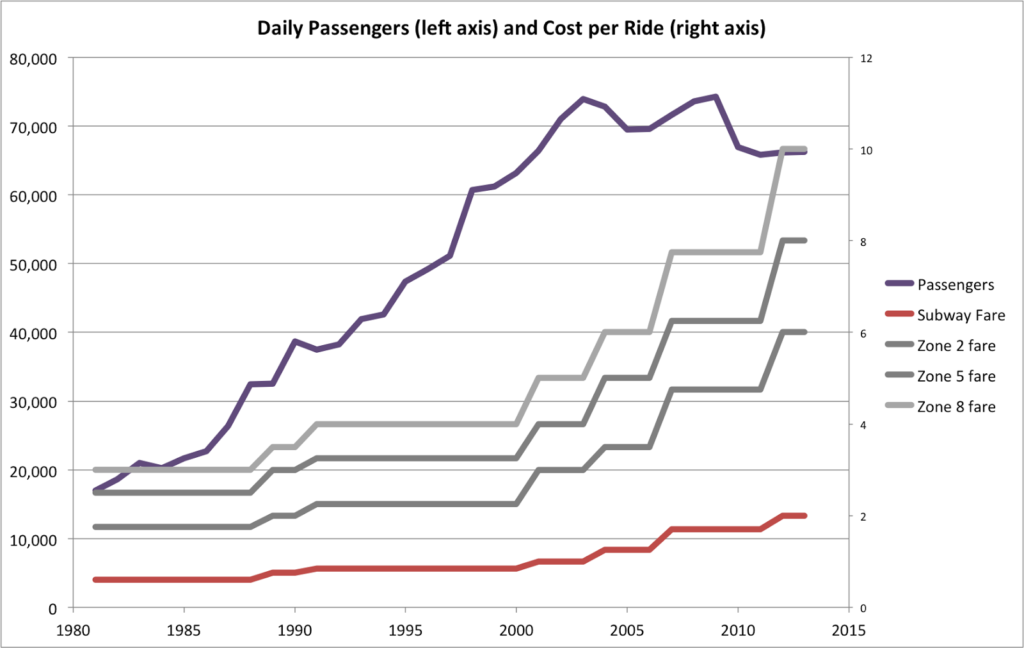

I-93 is the most heavily-traveled interstate bus corridor in to Boston of any length. Between 7 and 10 each morning, 27 buses travel from 495 to Boston (mostly private carriers from Hanover, Concord, Manchester, Nashua and Andover, Mass.). Another 21—Logan Express and MBTA—enter at or near 128, and 21 more MBTA buses enter the roadway in Medford. Most of these buses sit in traffic with everyone else. Once they access the carpool lane, and assuming they are operating at or near capacity, they transport 3500 people—about 1200 per hour, even though there is only a bus every three minutes. The capacity of a lane full of single occupancy vehicles is only about 1800, and in heavy traffic, it’s less. A better facility might also see buses coming down I-95 shift to 495 and 93 to avoid traffic on Route 1 as well, and encourage more people to ride.

And these are the statistics without any major benefits for ridership. These buses cope with the same traffic as everybody else in the morning and in the evening. Their operators are hamstrung by unpredictable traffic conditions which can cause schedules to run an hour late, or more. And there is no real time savings for riders. There is definitely a cost benefit versus driving, but the buses can’t go any faster than cars on their own. However, an HOV lane the full length of I-93 in Massachusetts would dramatically improve these commutes. It could be built for minimal cost by cannibalizing a lane off the current roadway. It would only require infrequent entrances, and exits before Boston would have to be minimized to preclude the possibility of the mainline backing up in to the HOV lane. It would allow buses to standardize schedules, and attract new ridership based on time savings—many of whom would otherwise be on their own in cars on the road.

An HOV lane would also attract carpoolers, and to keep the traffic flowing a minimum of three passengers might be feasible during high demand times. This might encourage

slugging from these far-flung park-and-rides in to the city. If the time savings were high enough—and at times avoiding traffic on I-93 can save an hour or more—many single-drivers would be keen to grab a couple of new friends for the ride.

Finally, this project could be paid for by tolling the carpool lane depending on the traffic conditions. At certain times of day, allowing single drivers to travel the length of the lane for $10 or more would raise significant revenue and allow those who wanted to avoid traffic to do so. While often derided as “

Lexus Lanes” such a system would be optimized first for traffic conditions and then for revenue. If the HOV facility was near capacity from carpools and buses alone, the price could be astronomical. If the rest of the road was mostly free-flowing, it would be low enough to entice a few drivers to save a few minutes without breaking the bank. And revenue from this lane could go to paying for the initial improvements, as well as funding parallel transit options.

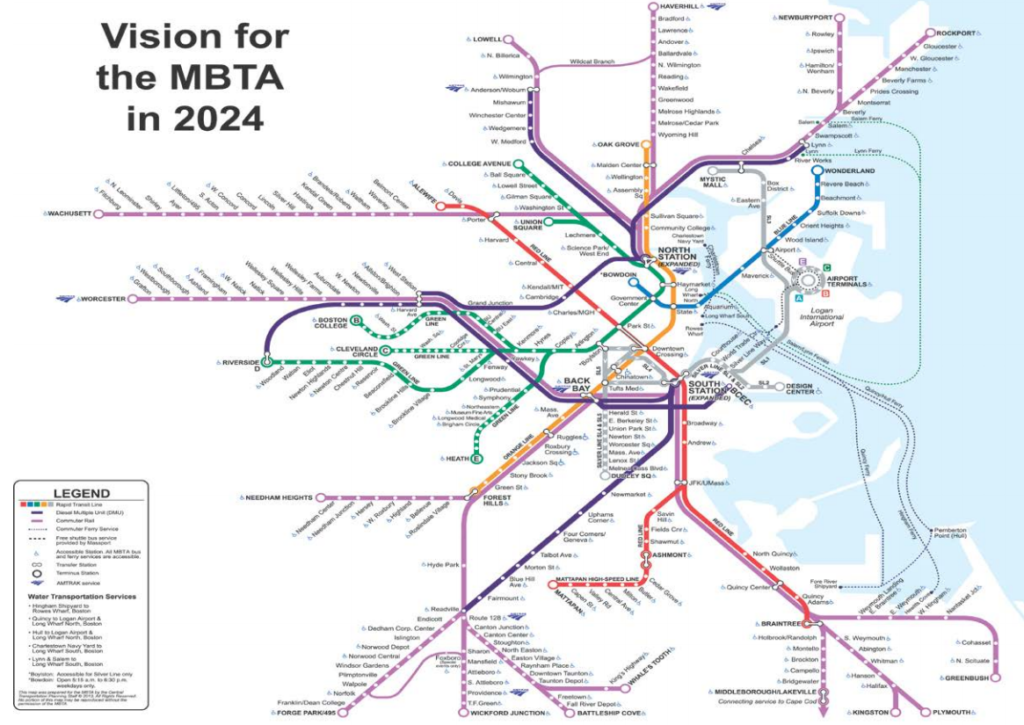

Finally, The Cost of Doing Nothing Is Not Zero. Basically, inaction on transit in this corridor will have negative repercussions throughout the region. Quashing a study because rail will require a subsidy (as opposed to $800 million highway widening projects, which apparently pay for themselves) is as bad policy as it is politics. Rail service would provide access to jobs in Boston from New Hampshire, but also access to job sites in New Hampshire from Boston. In theory, rail service would run express from Boston to Lowell in 40 minutes or less, and then provide access to the Spit Brook Road area, Downtown Nashua, Manchester Airport, Downtown Manchester and Concord. With gas prices poised again to break $4 per gallon, precluding access except by car—even to dense, downtown areas—is a good way to stagnate long-term growth.

New Hampshire has to realize that most of its population lives within the “commute-shed” of downtown Boston, and it is inextricably linked to the larger city to the south, even as it derides it with shouts of Taxachusetts and worse. If New Hampshire’s goal is to provide better access on I-93—and it seems that it is—it has to have some sort of alternative from Massachusetts to actually improve the access that I-93 provides. Whether this is a high occupancy facility or rail transit—or some other mode—is a valid question. Whether it should be studied, however, is not.

( * It should be noted that while the Amtrak Downeaster services has several stops in New Hampshire, it is funded solely by the State of Maine. New Hampshire benefits dramatically from the service, which transports hundreds of Granite Staters to Boston every day.)