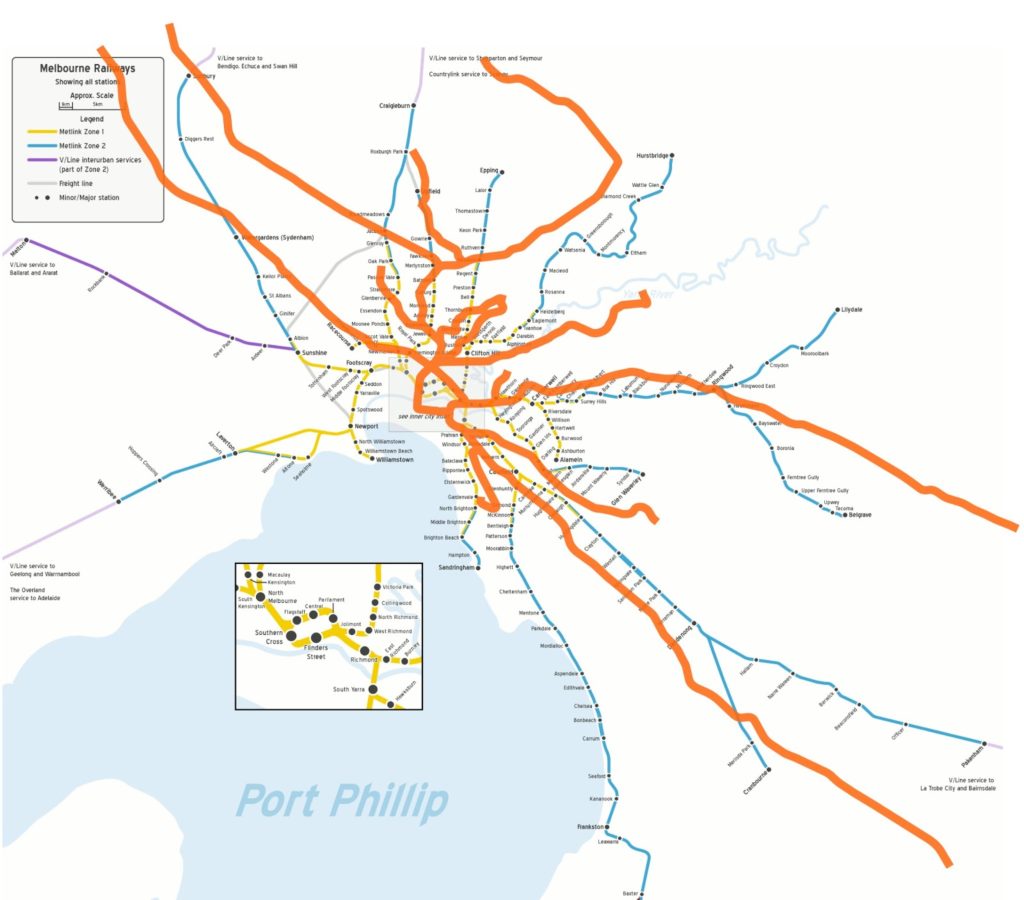

A quick follow-on to my previous post on clock face scheduling. I mentioned the commuter rail system in Melbourne, Australia. It’s being rebranded as a Metro system with service levels to match. Even the longest branch line has midday service at least every 30 minutes, and most of the system has service every 20, 15 or 10 minutes, with clock face scheduling at all times.

Melbourne has 231 miles of electrified route, and serves about 700,000 passengers daily. That’s more than any commuter rail system in the US outside New York City (where three systems combine with about a million riders), more than double Chicago (a city with a population more than double Melbourne) and five times the ridership of Philadelphia and Boston.

Why compare Melbourne and Philadelphia? Both operate almost solely electric trains. They have nearly the same track length (about 221 miles for Philadelphia; Boston has almost double the track length with not much more ridership). And, most importantly, both linked two separate commuter systems with downtown tunnels in the 1970s and 1980s to improve efficiency in their systems.

Now, while it’s not apples to apples, it’s not apples to oranges. Both systems have about 1 million daily riders on their non-regional rail systems (270m in Melbourne, 290m in Philadelphia). Melbourne lacks any heavy rail subway, but has an extensive tram network; Philadelphia has heavy rail, light rail, streetcars and buses, with the buses carrying slightly more than half the load. Both cities have populations in the neighborhood of 5 million. Melbourne is much more isolated (Philly is less than two hours from New York, Baltimore and DC, Melbourne is that far from Geelong, Bendigo and Ballarat) but both have extensive, car-centered suburbs.

Both systems saw ridership bottom out in the early 1980s and have doubled (in the case of Philadelphia, tripled, although the low occurred after hundreds of miles of diesel service was scrapped and a crippling strike severely cut ridership) since. Both run under overhead wires. Both have quadruple-tracking on some core segments.

And Melbourne’s regional rail system carries more than five times as many passengers as Philadelphia’s.

There are a bunch of reasons why this is the case. Two of the biggest: Frequency is certainly one—Melbourne has more commuter rail lines with 30-minute-or-better headways all day than there are in the entire United States (*)—only two SEPTA lines operate more-than-hourly. Melbourne’s two-zone fare structure, with full integration with bus and tram lines (this is the subject of another post entirely), also makes it much easier to use the system.

It would be a very interesting exercise to see if running SEPTA with Melburnian service levels and a simplified fare structure dramatically increased ridership—especially if someone has $100m burning a hole in their pocket.

* Actually, Melbourne has 11 full lines with at-least 20 minute headways and two others with 15 minute headways before branches split near their termini and have service every half hour. This is more than the 9 lines in the US which have 30 minute service patterns. BART and Washington Metro’s outlying branches could be seen as a similar system to Melbourne’s, but they were built in the ’70s; most lines in Melbourne were built in the 1800s.