It’s transportation week here in Boston, apparently, what with the Globe Spotlight series dropping and Boston Magazine publishing their list of 40 ideas for transportation.

I started reading the 40 ideas piece and with each one had a reaction. Mostly “yeah,” “mm-hmm,” or “what, are you out of your goddamn mind?” Then I realized: I should rate these. On a scale of 1 to 10. On my blog. Because who wouldn’t want to read one person’s ranting about other people’s ideas, rated on a 1 to 10 scale.

Well, a lot of people. But what if … two people each rated the ideas, on a 1 to 10 scale. That’s a little more interesting. Certainly more fun to read. And when I think of rating transportation on a 1 to 10 scale, I think of one person: Miles “Miles on the MBTA” Taylor (well, now that he’s in undergrad in Philly, he’s going by “Miles in Transit” but we know where his loyalties lie.)

That’s right: guest co-blogging this post is the one and only Miles on the MBTA.

GET EXCITED. Set your snark detector to high.

A few notes before we dive in. First, these are listed in the order they appeared in the Boston Magazine story (on several different pages), not based on our rankings (so you don’t have to jump around, note that the magazine has the ideas grouped by mode, and I’ll link to each page). I set some ground rules: points for (or against) creativity, feasibility, is it a “big” idea, and not “staying in your lane,” i.e. if someone works for an organization which advocates for x, and their proposal is to do x, it’s not as exciting. Also, it’s worth noting that Miles wrote his ratings and responses without looking at mine.

So, we’re off. Thanks, Miles! And somehow this is under 4000 words (I should stop typing!).

1. Congestion modeling as an investment (John Fish)

Ari: 9. Good idea, coming from a business leader. Good framing. One question: what do we do with the money? Does it go all towards transit? What if it was just put in an account and divided by the number of people in the state and returned as a tax rebate a la Canada’s carbon tax? Is this a good idea? How do we implement?

Miles: 8. Congestion pricing is awesome and Boston needs to do it. My one qualm: it’s really tough to find alternate, non-driving ways of commuting from low-income gateway cities like Brockton or Lawrence when the Commuter Rail is so inadequate. There could be equity issues here.

2. Tax garage parking (Ari!)

Ari: 10. Perfect. Do it. (But actually, a good idea, lots of precedent elsewhere, and, yeah, I’m going outside my usual transit “lane.”)

Miles: 10. Ew, Ari Ofsevit wrote this one—I can’t stand that guy. But seriously, this is a no-brainer, and every other major city has done it already.

3. Be less of a Masshole (Kenny Young)

Ari: 4. Fine idea, but doesn’t really do much. Sure, calming down is good. Looking at photos on your phone, however … demerits for that.

Miles: 3. Um, okay. Seems pretty fluffy to me. And aside from the phone use while driving (which doesn’t seem like a great way to “save transportation”), the bit about “singing at the top of your lungs” perpetuates the fact that it’s just you and your car—i.e. the geometry problem that got us into this mess in the first place. I like his title, though: “Personal driver, Kenny’s car.” That’s pretty funny.

4. Make drivers suffer (Sue O’Connell)

Ari: 9. Yes! Pedestrianization! Make it hard to drive! Although free transit is fraught.

Miles: 8. Pretty much a grander version of number 1, and it sounds amazing. I love the idea of having a city as painful to drive in as Amsterdam. O’Connell even addresses the potential equity problems with higher fees for having cars. It’s a lot, though, and pretty much a utopian vision with the current administration.

5. Late night transit (Garrett Harker)

Ari: 8. Make Boston more of a late night city? Great. Transit for late night employees? Great. Doing this through TNCs? Not sure what happens when they have to make money someday.

Miles: 6. Yeah, it would be nice to live in a city that doesn’t go to bed at 8 PM. Using a more vibrant nightlife to fuel 24-hour transit is an interesting idea, but I think the latter has to come before the former. And while it’s neat that he partnered with Lyft to get his workers home cheaply, early-morning MBTA buses get too packed to do something similar for them.

6. Autonomous cars for all (Lee Pelton)

Ari: 1. Can I go to zero? Can I go negative? Give me a break. We can all ride in an autonomous car driving around the city because there’s so much room on our roads. Seriously, Emerson? Has this guy ever looked out the window? Autonomous cars are cars. Cars in the city are bad. Please. I’ll keep him at 1 because at least he admits this is decades away.

Miles: 1. A Celtics game at TD Garden lets out. You have 20,000 people trying to get home. As the line of 20,000 individuals vehicles gets backed up along Causeway Street (and Commercial Street, and Atlantic Ave, etc. etc. etc.) waiting to pick everyone up, those autonomous cars suddenly don’t look so efficient, do they? What a shame.

7. Smarter tolls (Chris Dempsey)

Ari: 8. Good idea, should be implemented, but points off for staying too much in your lane. In other words, we know what to do? Now, how do we do it?

Miles: 9. It’s very much inside the box, but using existing infrastructure to cheaply instate congestion pricing is a great idea. The Tobin Bridge is a good place to try it, but the plan should come with a bus lane for the 111—goodness knows it needs it.

8. Fix potholes (Ernie Boch, Jr)

Ari: 2. If you don’t like potholes, move to Arizona or somewhere that doesn’t have freeze thaw cycles. Or start paying more for the roads, you Trump-loving sycophant.

Miles: 2. Are the potholes ruining your beautiful expensive cars? I’m playing the world’s smallest violin for you. Not a 1 because buses drive on the roads too, so at least they would benefit too.

9. Get cars off the road (Kristen Eck)

Ari: 10. Simple, and coming from the traffic reporter. More people without more roads = more traffic.

Miles: 6. It’s a good mindset to have, but the implementation is really vague and doesn’t do anything to fix the alternatives to driving. Sure, we can subsidize MBTA passes for employees, but if the Red Line breaks down for the 15th time that week, how valuable will those passes look?

10. Worcester-to-Boston (Mary Connaughton)

Ari: 8. Fixing the Turnpike outside of Allston is a good idea. But fixing the Worcester Line would do a lot more. People on Twitter think this could be done with toll revenue. Both, and?

Miles: 6. Kind of a mishmash of ideas here, some good, some bad. Improving Worcester Line service is a no-brainer, but keep the added service going past the time of construction, unlike what this entry seems to suggest. Fixing the monstrosity known as Newton Corner, fantastic. Increasing parking at Commuter Rail stations…fine at some of the more middle-of-nowhere ones, I guess. But building I-90 at grade just to make the project go faster? Hope you like diesel fumes!

11. Fix signage (Scott Ferson)

Ari. 2. This guy doesn’t seem to like the MUTCD. He rails against control cities. And he doesn’t understand that the exit number sign already indicates whether an exit is a left-hand exit or not. Not sure what this would do for congestion even if it made him feel better.

Miles: 3. I mean … whatever, man. Massachusetts has its share of crazy signs, but a lot of this comes down to the insane interchanges rather than problems with the signage itself. I’m not against the idea, per se, but its inclusion just feels like filler.

12. Give commercial vehicles more space (Ana Cristina Fragoso)

Ari: 5. Sort of a fine idea, I guess. More and better loading zones would make sense. Moving some stuff to rail? Fine. Ferries? Meh. More important are probably local loading zones, and getting people to stop ordering stupid shit from Amazon Prime and getting single rolls of toilet paper delivered by cars. We need a bit less Veruca Salt (“Don’t care how, I want it now!”) syndrome and a bit more walking half a mile to the corner store.

Miles: 5. Points for being a unique consideration (it’s not something I’ve ever thought about). I like the idea of focusing on other ways of getting freight into the city, although it is going to be a tough sell to dedicate entire roads to commercial vehicles.

13. End distracted driving (The Rev Laura Everett)

Ari: 10. Yes! Put your goddamn phone away. Not out of your hand. Not a glowing rectangle next to your face. No. Away-away. In the glove box until you get to your destination. Look at the directions before you start driving, like we used to do before we had phones. If you don’t know where you are going, you shouldn’t be on the road.

Miles: 8. Yeah, okay, let’s do it! This is by no means groundbreaking, but any way to eliminate pedestrian deaths is a good thing.

14: BRT (Julia Wallerce)

Ari: 8. BRT is great, but a) not going to solve all of our problems, and b) very much in Julia’s lane. But, yeah, put in some goddamn bus lanes already.

Miles: 8. BRT is a fantastic way to improve capacity in Boston’s overcrowded bus system. While this is a rosy look (how many Boston streets are wide enough for center-running BRT?), it’s still a great system to strive for.

15. Better interior bus design (Zuleny Gonzales)

Ari: 10. I was on the 70 and an already late-and-full bus was delayed several minutes while the driver helped a mobility-impaired person safely board. Plus the driver had to deploy the ramp by hand because it was broken. Making buses work better for people with mobility issues makes buses work better for everyone (goes for trains, too).

Miles: 10. Absolutely needed. If we can make riding the bus easier for everyone, especially those who are disabled, then not only will more of those riders take the bus, but speeds will be increased—I can’t be the only one who internally groans when someone in a wheelchair gets on and I know we’ll have to endure the two-minute strap-in process. It’s not the person’s fault, it’s the vehicle design.

16. Make way for buses (Jarrett Walker)

Ari: 8. Bus lanes and bus lane enforcement. Not a bad idea at all. Getting the police to care, though …

Miles: 10. I’m not a Jarrett Walker fanboy, I swear! Seriously, though, bus lanes are sorely needed in this city, along with proper enforcement. It’s definitely inside the box, and many bus lane projects are already happening, but there’s no denying that if we want to fix Boston’s bus problem, bus lanes are objective number 1.

17. Blue Hill Ave buses (Quincy Miller)

Ari: 10. Blue Hill Ave is the top corridor in the state for BRT. Tear out the concrete medians, put in BRT, and plant some trees.

Miles: 10. This is one of the only corridors where the treatment in number 16 would work. Plus, the 28 is the MBTA’s highest-ridership bus route—what better place for a BRT line? Redundant to the others, but I can’t argue with true BRT on Blue Hill Ave.

18. Electrification (Adam Gaffin)

Ari: 10. Adam gets it.

Miles: 10. Everyone knows this is sorely needed. It’s been talked about to death already, and it seems like the only people holding back are those up at the top. Let’s do it.

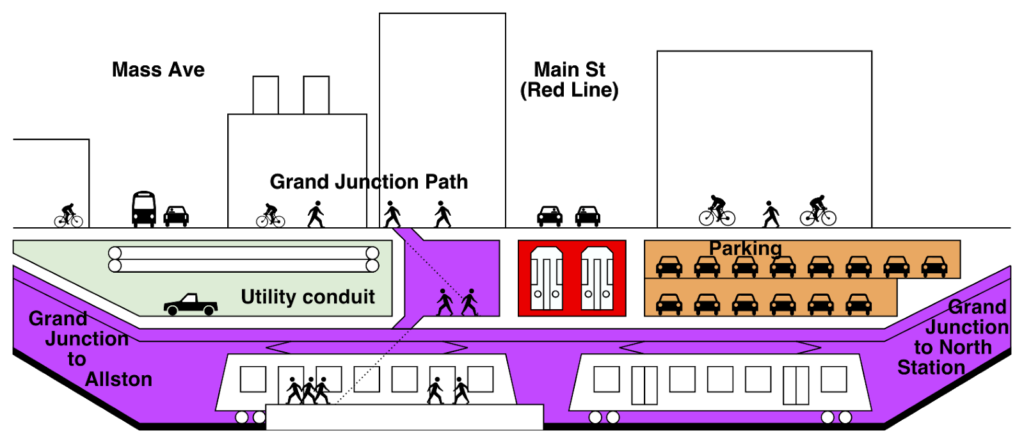

19. Build the Grand Junction (C.A. Webb)

Ari: 10. The Grand Junction is the best ROI for a rapid transit “crosstown” link. North Station-“Cambridge Crossing”–East Cambridge–Kendall–Cambridgeport–Allston. It doesn’t sound like a busy transit line today, but with ongoing development, that order of stations may soon read something more like North Station–Kendall–Kendall–Kendall–Kendall–Harvard (Allston). With the Allston project, the time to do this is now.

Miles: 8. More transit to Kendall Square is really important, and the Grand Junction is the only existing rail asset there besides the Red Line. I’ve never been a giant fan of the whole “run Worcester trains via the Grand Junction to North Station” thing, though—you end up with a reverse-branch that could potentially limit the number of trains serving South Station. Instead, how about a frequent shuttle from Allston to North Station?

20. Gondola!!!1! (Roger Berkowitz)

Ari: 1. Bus lane!!!1! (Or if you want a subway, put trains in the Silver Line tunnel. Remember, the gondola doesn’t work just because you say words.)

Miles: 1. THE SEAPORT GONDOLA IS BACK!!!!!! Look, we have a “subway tunnel service” to the Seaport—it’s the Silver Line, and yes, it is insanely overcrowded at rush hour. Convert it to light rail and suddenly you’re going to see a lot more capacity for that “subway tunnel service.” And reopen the Northern Ave Bridge for car traffic? Ever heard of induced demand?

21. Big rail (Kathryn Carlson)

Ari: 10. Yes, regional rail! And let’s remember, those cost estimates are … high. But $30 billion (less, though, because this includes the cost of buying rolling stock, which the T has to do no matter what propulsion system is used) over the next 10 years is $600 per person per year inside of 495, much of which you could get from the feds, to completely transform the regional transportation system. It’s really not that much.

Miles: 10. Another one that’s been talked to death, and pretty much every transit advocate agrees this needs to be done. Carlson even brings up the hefty cost and defends it.

22. Better PR (Max Grinnell)

Ari: 4. I mean, better PR would be nice, but it won’t make the trains run on time.

Miles: 2. I don’t think Max Grinnell reads the MBTA’s Twitter replies. When they’re stuck in a line of trains trapped behind a broken signal, people don’t feel any better by looking at cutesy PSAs. I guess it’s a nice thought, but it’s nothing more than that: a nice thought.

23. Widett transportation hub (Tom Tinlin)

Ari: 2. Oh, it’s Track 61 again. Like the gondola, it also still doesn’t work just because your mouthparts move.

Miles: 2. Points for originality, but I’m not quite sure what the goal is here. “A Widett Circle station could let commuter-rail passengers from the southeast get to Back Bay or Ruggles without going all the way to South Station.” What? How? Track 61, I guess? And Tinlin talks about connecting the Red Line and Commuter Rail here. So there’d be a new Red Line subway station? With a 700-foot connection from Dot Ave to a new Commuter Rail station? This had better coincide with a redevelopment of the area, or else you’re going to end up with a lot of wasted money.

24: Franklin Park Bike Hub (Elijah Evans)

Ari: 7. This would be great, having Franklin Park be more usable by bicycles (and overall, some of the paths there are overgrown, it’s kind of weird). And I do like the idea of making roads nearby more bike-friendly. But it’s not going to solve the regional transportation issue, even if it helps some.

Miles: 7. This seems like mostly a PR campaign to make local residents more aware of the ease of biking through Franklin Park, which is not a bad thing. Importantly, though, it would have to come with better bike infrastructure on surrounding roads—the park itself isn’t really gonna get you anywhere.

25. Bike the last mile (David Montague)

Ari: 6. A fine idea, although congestion isn’t always the last mile. This is also very much in the lane for David Montague, who owns a folding bike company.

Miles: 4. A novel concept for sure. But think about a cold winter day: you’re in your warm car, and you come to the “park-and-bike” lot—do you really want to get out of your private vehicle and get on your freezing bike through the pounding snow instead? Probably not. This isn’t a problem with a typical transit-based park-and-ride system.

26. Share the road (Jenny Johnson)

Ari: 9. Give bicycles better facilities and they’ll be more law abiding? Yup. Go to Europe and see how design begets ridership? Sure.

Miles: 10. Johnson’s anecdote about bikers waiting at the light in Vienna really drives home the idea that people will follow the rules when they’re fair. In Boston, bikers get so little compared to cars—of course they’re going to rebel and run the light. Give bikers the safe corridors they need, and you’ll see a lot more harmony on our roads.

27. Helmets for Hubway (Joanne Chang)

Ari: 3. I mean, fine, but helmets don’t keep people from riding BlueBikes. In fact, these upright, Dutch-style, stable bikes are probably the ones with the least need for helmets. This does basically nothing. (I’m surprisingly libertarian on bike helmets.)

Miles: 3. No one wears helmets in Amsterdam, because bike fatalities are ridiculously low, because the streets are designed for them. While helmets may make you feel safer here, they’re not doing anything to actually solve the transportation problem for bikers.

28. Connect the paths (Juliet Eldred)

Ari: 10. NUMTOT! But even if it wasn’t NUMTOT-in-chief @drooliet, it’s also a great idea. The real last mile issue with bikes (see above) is that the last mile of a bike trip is often unsafe. So people drive. Let’s cover the city with a web of bike lanes, instead of traffic lanes.

Miles: 10. As a proud NUMTOT, it is so cool to see that Juliet made the cut here. And her idea makes so much sense: why do we have these fancy separated bike lanes that connect to lines of paint on the road? We can’t wave a magic wand and instantaneously get separated bike lanes on every street in the city, but we can at least try to connect the ones we have.

29. Podcars (Bill James)

Ari: 1. No.

Miles: 1. Aahgahgaghhhghhh.

30. Road diets (Joe Curtatone)

Ari: 9. Yes. Now, can you call over to Marty and get Boston to stop shitting all over this?

Miles: 10. Putting aside the fantastic points, ideas, and examples put forth here, it’s amazing to see that this was written by an elected official, the mayor of Somerville. It gives me hope that there are people on the top who know what’s going on and want to fix it.

31. Flying cars! (Gwen Lighter)

Ari: 1. Also no. Not as crazy as podcars because they aren’t low-capacity elevated railroads, but has anyone talked to the FAA about this?

Miles: 1. What? Is this a joke? Am I reading an Onion article?

32. Fare equity (Tanisha Sullivan)

Ari: 8. Fare equity is great. Implementation is, well, not as easy. Price discrimination allows us to do things like keeping certain services from being even more overrun when they are already near capacity. Without this, we get a tragedy of the commons with poor service and long wait times like, well, like the roads at rush hour. (Off-peak pricing, now, there’s an idea!)

Miles: 7. This is a good, moderate look at how to improve access for people. Free MBTA fares for students and seniors is more realistic than making the whole system free, while encouraging flexible work hours would ease rush hour traffic a bit. Nothing groundbreaking here, but some fine ideas.

33. Ferries (Alice Brown)

Ari: 5. Ferries are useful for a few demand corridors, but not really a game-changer regionally. And this is very in-her-lane for the head of Boston Harbor Now.

Miles: 4. Utilizing our water assets and creating new ferry routes is good in theory, but who’s taking a ferry from East Boston to Long Wharf when the Blue Line exists? Maybe the people in the expensive luxury homes near the water, but not much else. East Boston to the Seaport is better, but even then, bus lanes in the Ted Williams for the SL3 would help here, too. I just don’t want Boston to end up with a repeat of the NYC Ferry http://secondavenuesagas.com/2019/10/06/its-time-to-stop-subsidizing-the-nyc-ferry-fares/.

34. Think outside the box (Jim Canales)

Ari: 7. Let’s be a world class city with outside the box ideas is fine, but vague.

Miles: 7. This is vague as heck, but the general call to [waves hand] think outside the box is solid.

35. Dockless scooters! (Lama Bou Mjahed)

Ari: 2. Small-wheeled death traps which are expensive and still lose money. Pass.

Miles: 2. This is listed under “Big Ideas”? Dockless bikes and scooters are already being implemented around the country, and even in the Boston region! It might take a few (a few) cars off the road, but this isn’t the big solution we’re looking for. And Bluebikes already has great coverage that’s expanding.

36. Robotaxis (Karl Iagnemma)

Ari: 1. Hooray, more cars! Using technology we don’t have! Magic!

Miles: 2. Okay … I guess it’s not hyping these things as a full-on takeover, but rather a low-cost last-mile solution that’s apparently being implemented in Vegas already. One point added for being realistic.

37. Teamwork (Patrick Sullivan)

Ari: 7. Getting people together is great. But as the Globe points out, if they are all subsidizing driving, it doesn’t help that much.

Miles: 6. Working with companies to open up new transportation options…okay, I can roll with that. But the example of the North Station/Seaport Ferry shows the flip side of it: it’s great for members of participating companies, but for members of the public, the ferry is near-unknown, and you can only buy tickets online in advance. These partnerships need to ensure that the public can benefit as well, not just the private companies involved.

38. Listen to users (Ambar Johnson)

Ari: 8. Not necessarily a big idea, but having a better way to have public feedback with the agency and cities and towns, especially outside of public meetings attended by old white people, would be good.

Miles: 10. I mean … it’s probably the least revolutionary idea on here, but it’s also one of the most obvious. The users know best, and the piece summarizes it well: “Listen and trust their judgement, and just implement it.”

39. Invest in Gateway Cities (Tracey Corley)

Ari: 9. Yes. Gateway cities are an opportunity to build more housing near transit, and build more walkable, livable areas people want to live. Millennials don’t necessarily want to be in Boston (or Cambridge, or Somerville) but to live in a walkable, urban community with amenities and good transit. Gateway Cities provide this opportunity.

Miles: 8. The idea of gateway cities being self-contained, you know, cities that are disconnected from Boston is such an alien idea, so this gets major points for being outside of the box. And mention RTAs and you’ve got me hooked—the transformation of gateway cities needs to be accompanied by improvements to their bus systems, which vary wildly in quality. Regional Rail isn’t mentioned at all despite being a key factor in gateway city revitalization, though.

40. Mayor of 128 (Amy Dain)

Ari: 6. Fine, but reducing car use along 128 will be quite difficult unless we nuke all the development along 128 and rebuild it very densely around transit stations along 128.

Miles: 7. Sure, I guess. It would be good to have someone looking to the future of a corridor that is really screwed up right now. Smarter future development will at least prevent more traffic from using 128. As a big final proposal though, this is a little underwhelming.