[* Kind of, and only at certain times of day. They don’t anymore.]

Before the pandemic, the MBTA relied on Commuter Rail fare revenue. In 2019, the service accounted for less than 9% of total transit system rides (about 32 million) but 36% of fare revenue: about $250 million dollars. While bus and transit fares are relatively low, flat fares ($1.70 and $2.40, with free transfers), Commuter Rail fares start at $6.50 (with a few exceptions) and go up from there, to more than $12 for trips extending more than 30 miles from Downtown.

There are exceptions. Fares within 6 miles of Downtown Boston, including to Chelsea, West Medford and Allston, are priced the same as a subway ride. The Fairmount Line, which serves low-income neighborhoods of Boston, is priced at the same, lower level. “Interzone” fares, for trips between outlying stations on the same line, give about a 50% discount compared to a trip from the same station to Downtown. Overall, fares per mile are about the same as for trips on the bus and rapid transit system (35 to 40 cents per mile), although Commuter Rail fares per mile vary considerably: a trip from Belmont to Boston costs $6.50 for 6.5 miles ($1 per mile) while a trip from Worcester costs $12.25 for 44 miles (28¢ per mile).

There was some sense to Commuter Rail fares. The Commuter Rail system was optimized for a balance of fleet constraints, overall public utility and fare revenue, and generally in that order. But only at rush hour.

Transit systems have very high up-front costs to provide a base level of service, but the marginal cost of adding passengers to this base level of service is nearly zero. In the case of Commuter Rail, the fixed costs involve the right-of-way (capital costs and maintenance), maintenance facilities, signaling, control center, customer service, stations, and other fixed assets. These costs are fixed, whether you run 1 train per day or 100, and account for much of the cost of the railroad. The first decision the agency has to make is the base level of service: how many trains to you need to provide an even level of service during the day.

Pre-pandemic, the Commuter-oriented system set this at a very low level. In general, trains ran about every two hours on each line (you can find an archive of schedules here). In some cases, trains were slightly more frequent (the Lowell Line had hourly weekday service), but two hours was normal on most lines, even those to Providence and Worcester. In addition, since most trains spend the night at outlying terminals, they need to be serviced and fueled at downtown termini, meaning that trains would be cycled in and out of these every-two-hour service levels for service (although fueling and inspections do not necessarily occur daily). So the baseline cost of running the service depends on the number of trains needed to run the service at this interval, plus to cycle trains to and from centralized maintenance facilities.

In the case of the MBTA’s Commuter Rail system, the agency needed approximately 25 trains to provide this base level of service, so about 35 including trains being serviced (the rest are stored Downtown or elsewhere), of the 65 train sets operated each day.

The next decision, which is based on the base level of service, is how much additional service to add at rush hour. The cost of adding some service at rush hour is relatively low: the trains which are being serviced during the base period can be pressed into service, so the marginal additional costs to rush hour service comes mostly from additional labor. Beyond these trains (about a 50% increase in service, so a train every 1:20 or so), however, costs for additional service increase quickly. To operate a rush hour-only train the costs include:

- The cost of additional labor, which often results in a split shift where the staff works in the morning and evening with a “midday release” during which they are paid half-time.

- The cost of midday layover facilities, or “parking spaces for trains.”

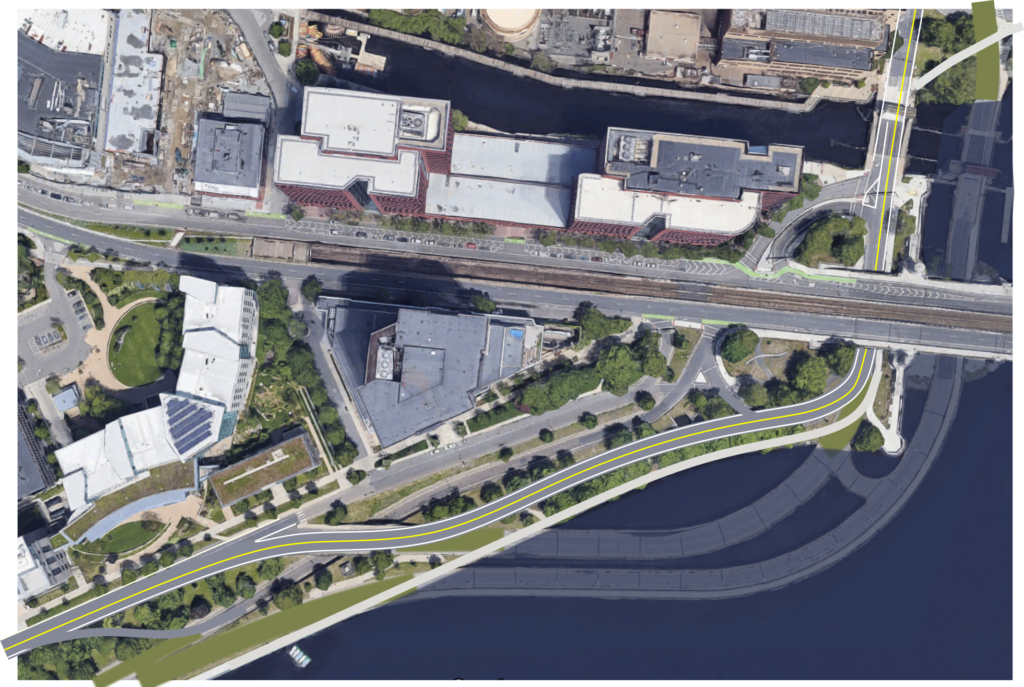

- The cost to operate empty trains to and from these midday layover locations, which in some cases are up to 10 miles from the terminal station. In the case of the T, this meant finding room for about 30 trains during the middle of the day. (I’ve argued before that these trains would be better used providing more service).

- The costs for the actual additional trains. Before the pandemic, three Commuter Rail train sets made just one round trip per day, and several others made just two, meaning that they were idle for 19 to 21 hours per day, so the capital cost of a train set (about $25 million) had to be amortized across this limited service. (The single-trip trains were generally the longest, largest trains, with 8 or 9 double-decker coaches carrying nearly 2000 passengers.)

The MBTA generally scheduled as many trains as they could fit on their lines without major capital improvements. There are several limiting factors to the number of trains, including often-antiquated signal systems, sections of single-track, and terminal design and congestion. The number of trains varied by demand by line (which, in many cases, depends on parking lot capacity, since the T has made the (poor, in my opinion) decision over the years to create park-and-ride stations and not stations with high density housing nearby), line capacity, and congestion at each terminal. In some cases this meant four trains per hour, in some cases fewer than two.

Given this service, there are two ways to set fares. One is to maximize the utility of the system (getting as many people onto each train as possible) and one is to maximize revenue (set fares where they will generate the most revenue, even if it means fewer passengers). The T’s fares sort of split the difference. The fares are almost certainly not revenue-maximizing; every fare increase analysis has shown that when fares are raised, ridership drops, but the elasticity is such that it drops by less than the fare is increased. Fare maximization would have less-frequent trains (reducing marginal operating costs) carrying only the riders who for whom the train was time- and cost-competitive with driving. In fact, such a system might have come close to revenue neutrality. Running emptier trains, however, would mean more people driving on the road and more congestion and pollution, which have regional negative externalities.

In general, the agency matched passenger demand to train size, meting out train cars across the system based so that the trains would be full, but not too full (when smaller sets had to be substituted in, passengers were sometimes left behind). If fares were much lower, the trains in the system would not have been able to handle the crowding. So if the MBTA’s Commuter Rail fare system was optimized in any way, it optimized overall utility given the fleet and system constraints, and then revenue maximization given the utility. There’s nothing inherently wrong with this.

Now, is this actually how Commuter Rail fares were set? Of course not, that would make too much sense. Commuter Rail fares are higher because Commuter Rail fares have always been higher. Before the Commuter Rail system was integrated into the MBTA, fares were even higher than today. In 1971, a fare from Malden to Boston (before the Orange Line was extended there) was 95¢, versus a 25¢ subway ride. The equivalent of a Zone 1 fare was $1.10 and the equivalent of a Zone 8 fare was $2.20, which would be $8 to $16 today (these distance-based fares—in 5¢ increments—were changed to zone fares at some point during the 1970s, and multi-ride tickets were offered with a 20% discount, similar to passes today but without any reciprocity on subways and buses). Since the system was, at the time, operated by private carriers with an agency subsidy, they were more interested in maximizing revenue than utility (they certainly weren’t interested in providing service, and provided very little).

Once integrated into the MBTA, fares have generally been about 2.5 times that of a base subway fare for Zone 1 travel, with Zone 8 costing 4 to 5 times a base subway fare. Fares fell, relative to inflation, during the 1980s and 1990s (when Commuter Rail ridership grew most quickly), and have doubled, relative to inflation, since 2000. In 1999, the $2.00 Zone 1 Commuter Rail fare is equivalent to $3.31 in 2021 dollars, about half of the cost of a Zone 1 ticket today. While this increase is tied to rapid transit fares, and while commuters were willing to pay higher fares at rush hour, it has made the Commuter Rail much less price-competitive with driving at off-peak hours.

| Year | Zone 1 | Zone 8 | Z1 2021 $ | Subway |

| 1970 | $1.00 | $2.00 | $7.19 | 25¢ |

| 1971 | $1.10 | $2.20 | $7.91 | 25¢ |

| 1977 | $1.10 | $2.25 | $5.11 | 25¢ |

| 1990 | $1.65 | $2.75 | $3.52 | 75¢ |

| 1991-9 | $2.00 | $4.00 | $4.04-$3.31 | 85¢ |

| 2000-3 | $2.50 | $4.75 | $4.02-$3.74 | $1 |

| 2004-7 | $3.25 | $6.00 | $4.77-$4.36 | $1.25 |

| 2007-14 | $4.25 | $7.75 | $5.70-$4.94 | $1.70 |

| 2014-6 | $5.75 | $10.50 | $6.68-$6.43 | $2.10 |

| 2017-9 | $6.25 | $11.50 | $6.99-$6.75 | $2.25 |

| Current | $6.50 | $12.25 | $2.40 |

Data from 1970 and 1971 taken from a photograph of a fare tariff posted at the Wayland Station in 1971, during the last months of service there.

There are two problems with this system. One, the optimization was only valid for peak rush hour! During the midday period, even with minimal service with trains every two hours, the higher fares were less competitive with driving. At rush hour, the trains could generally come close to matching driving times (in some cases bettering them) given congestion, and were less expensive than parking. (In theory, the pre-pandemic revenue-maximizing fare may have been closer to Downtown Boston parking costs.) At other times, service was slower than free-flowing traffic and more expensive than off-peak parking rates. Yet even though there was plenty of room on the trains, prices remained the same.

In 2018, the T introduced $10 weekend passes, a steep discount over normal one-way fares. These proved wildly successful, and the elasticity was such that revenue actually increased, providing much more public utility while netting the agency more revenue. (A flawed MBTA analysis attempted to cut the program short and did for a few weeks—they wouldn’t want to threaten the public with a good time—until the FTA told them that, no, it was fine, and to carry it forward.) Theoretically, a similar product could be used for midday service (for instance, unlimited daily trips for $10, excluding inbound trains before 9:30, similar to Metra’s Lollapalooza pass of years past). This was never proposed or instituted, because of the second problem: the pandemic.

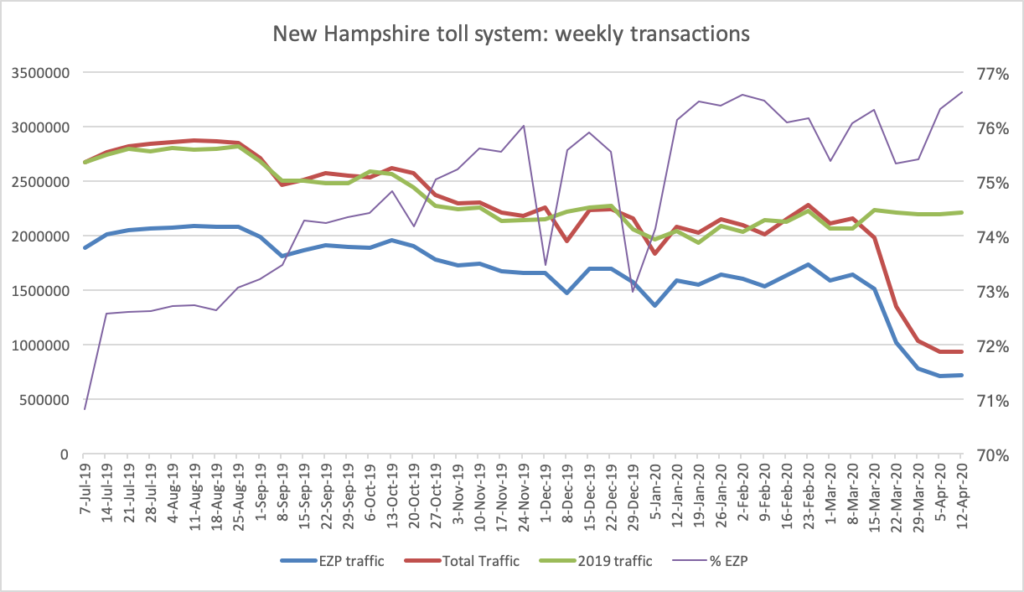

Transit ridership cratered after the pandemic, but it fell unevenly. Bus ridership on some routes fell less than 50%, and in some cases has nearly recovered to pre-pandemic levels. Rapid transit ridership fell more, but is also recovering. But Commuter Rail ridership fell by more than 90%, and it is clear that the 9-to-5 Commuter Rail market is unlikely to fully recover any time soon. The MBTA has responded to the changing trip patterns on Commuter Rail by flattening service: in most cases, there are now hourly trains on all lines, no matter the time of day (weekend service is still less), with only a few cases with more frequent rush hour trains. This provides quite a silver lining for the agency: they can provide more base service, without having the costs of midday staff releases, midday train storage and trains which are only in use for one round-trip per day. Anecdotally, ridership during rush hours remains quite depressed, but midday ridership and weekend ridership has shown significant recovery.

Fares, however, have not changed with the service levels, since the fares are still optimized for the previous 9-to-5 commuting crowd. Traffic congestion has returned, and while the peak traffic is not as congested as before the pandemic, overall volumes during the day are as high or, in some cases, higher. With ample capacity on the improved-frequency Commuter Rail system, it could provide a significant utility to the traveling public if it was priced more competitively. Yet it retains its peak-hour pricing.

The MBTA could experiment with Commuter Rail fares to provide more equitable service and attempt a different sort of optimization, choosing to optimize public utility first, and not maximize fare revenue until and unless trains experienced crowding. It turns out, however, that optimizing utility might actually increase revenues, as was experienced from weekend fares. It could also be an opportunity to make fares less complicated with fewer zones and more day-pass options. Imagine the following fare structure:

- $2.50 single trip in the MBTA bus/subway service area (basically inside 128, current zones 1 and 2), also available with a daily/weekly/monthly “link” pass.

- $5.00 single trip / $10.00 daily pass for trips originating at stations between 128 and 495 (current zones 3 to 6)

- $7.50 / $15.00 daily pass outside of 495

- $2.50 for “interzone” trips (trips not originating in what is today Zone 1A)

- Day passes also cover all buses and subways, single trip tickets allow free transfers to buses and subways.

This would set fares near buses and subways to the same price as the parallel transit service. In the past, the T has rationalized the higher prices on Commuter Rail by saying that if Commuter Rail prices were the same as local buses, too many people would crowd onto the trains (which may have been true). This is no longer the case! This fare system would mean that stations in places like Roslindale, Lynn, Waltham, Newton and Salem would have the same fare to Boston whether a rider took a bus, subway or train. That’s the product; moving people where they need to be. There’s no longer a capacity crunch excuse to price discrimiate. Furthermore, it makes the fare system much easier to understand. Instead of more than a dozen fares the T has today, it divides the system into three fare zones, and provides transfers between modes.

Beyond 128, prices would not be much different than prices in the late 1990s, when Commuter Rail ridership increased dramatically. With more midday service in these areas, there might be significantly more ridership at those times of day, since prices would generally be lower than driving and parking. And since the trains being operated have plenty of space, revenue may actually improve. It likely won’t hit the levels it did before the pandemic for some time, but we should be trying to maximize utility, not revenue.