Electronic tolling in the United States took a long path to implementation. EZPass was first developed and implemented in the mid-1990s in and around New York City, and began to spread elsewhere. Maine’s not-compatible TransPass system began around the same time, before being folded into EZPass in 2004. Massachusetts implemented the compatible, but differently-named (because, who knows) FastLane system in 1998, which was eventually folded into EZPass. Overall, EZPass-compatible systems stretch from Maine west to Illinois (still called I-Pass) and south to Florida (well, some toll roads in Florida). It is a reasonable example interagency cooperation—or of the size of the New York-area toll structure dwarfing the rest of the market—despite the inherent inefficiency of 40 separate agencies each with their own distribution and service networks.

I guess once the toll-taker jobs started disappearing each state still needed some agency jobs for patronage.

The longtime hold out to electronic tolling? New Hampshire. Maine’s system was in place in 1997, and Massachusetts in 1998. More than half of the system’s revenue is from out-of-state drivers, and the I-95 Turnpike—called the Blue Star Turnpike officially—likely contributes the highest ratio of out-of-state, so most of the drivers on the Blue Star were going from one state with electronic tolling to another through a facility without it. Once Maine switched to EZPass-compatible transponders in 2004, New Hampshire couldn’t even claim that there was a technological reason for the discontinuity.

New Hampshire finally put EZPass on their roadways in the mid-2000s, and phased out the tokens, converted the Hampton toll plaza into a one-way toll with the toll doubled to combat backups by having more lanes open and eventually converted two of the toll lanes into “open road tolling” or ORT, allowing vehicles with transponders to pass through the tolls at highway speeds. It now gives a 30% discount to people who use a New Hampshire-branded EZPass, even if they live out-of-state, leading some drivers (raises hand) to swap between Massachusetts and New Hampshire transponders at the state line.

There was one major problem with this implementation: the highway has four lanes. Even in the earlier days of New Hampshire EZPass use, many turnpike drivers used the electronic system. Yet the roadway was designed such that, if it were operating at or near capacity, the toll plaza would be a bottleneck if more than 50% of drivers were using the transponders, and since its busiest times are when out-of-staters are driving north for vacations from states with higher transponder use, although these less-frequent drivers appear to be less likely to have transponders. So when traffic peaks, the Hampton Tolls are the first place to back up.

Now, I’m not one to suggest that New Hampshire should be building wider or larger highways to combat congestion. Certainly not. But in the case of the Hampton tolls, they didn’t build a wider highway. They built too-narrow of a highway. The roadway is four lanes upstream and downstream of the tollbooths. It’s hard even to believe that it was any more or less expensive to build two through lanes instead of three or four. The gantries were built to allow an additional lane, but there are large barriers between the current ORT lanes and the parallel booth lanes. Maybe it’s cheap to make this change by just moving the barriers, but in that case: why hasn’t it been done? Maybe it’s expensive because it will require work on the base of the road and regrading, in which case, it’s a planning failure. What consultant green lit this?

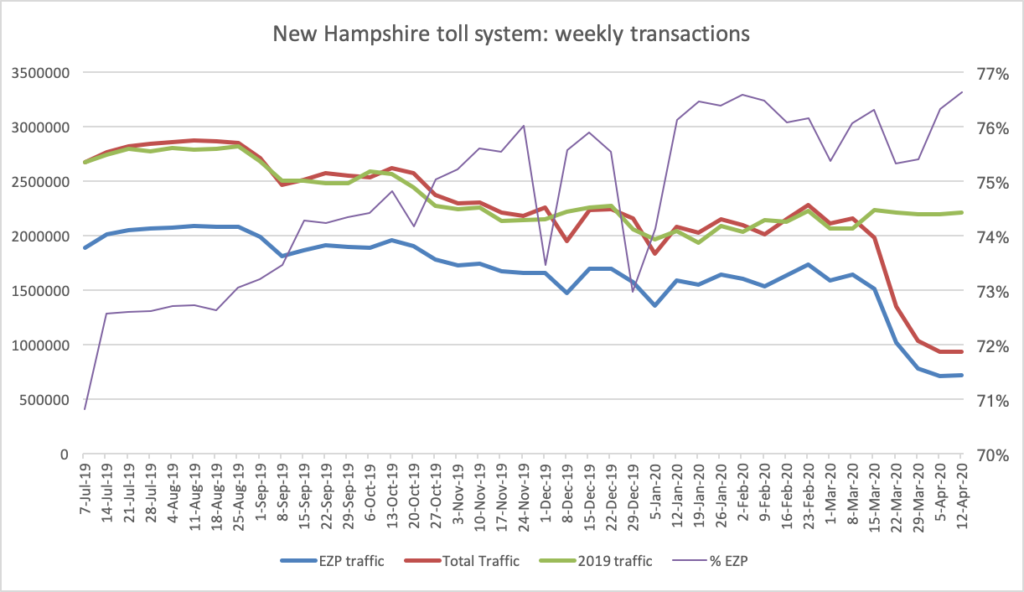

Why am I bringing this up now? Because I found (thanks to Casey McDermott of NHPR) New Hampshire’s weekly breakdown of toll data. I could write a blog post about the COVID drop off (the much richer data from the tolling facilities in Massachusetts hasn’t updated in a while, so I’m waiting on that), but instead, I want to focus on the percent of tolls paid with a transponder.

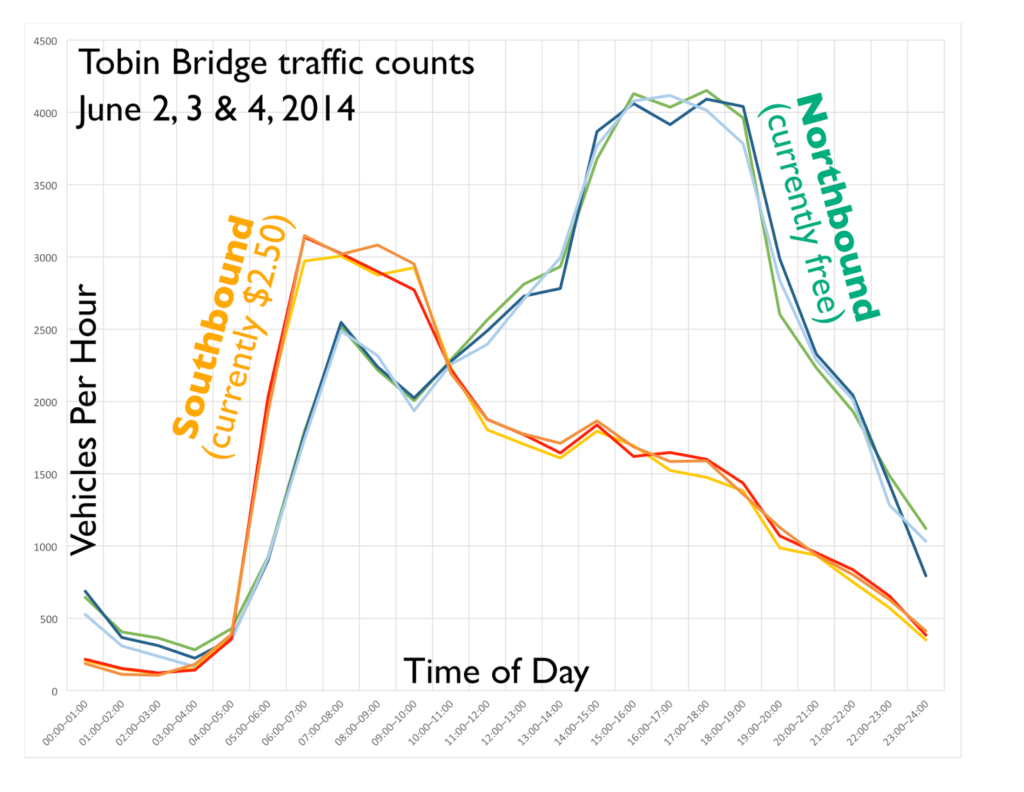

A few things to notice (beyond traffic dropping by two thirds during COVID):

- Even 10 years after implementation, the rate of EZPass use has been steadily increasing, from 72% in July of 2019 to 77% now. This means that of four lanes of traffic, more than three lanes-worth would be using EZPass.

- This may be due to seasonality. EZPass use rates are lower during non-tourist times. Rates were lower in the summer, higher in the fall (when more traffic is local) with local minima around the Christmas and New Years holidays.

- Overall traffic is quite variable, ranging from 2.8 million vehicles per week in the summer to 2 million vehicles per week in the winter.

- There is a steep drop off in traffic at the end of the summer, a local minimum in early fall, followed by a resurgence of traffic during “leaf season” in late September and early October. Variability for winter weeks may be due to snow storms reducing traffic.

The big takeaway is the first point: three quarters of New Hampshire toll road users are using EZPass, yet the toll booths are constructed such that only half (at Hampton) or two-thirds (at Hooksett) of the lanes are set aside for ORT. In addition to merging and sorting issues (cars on the right have to move left for ORT, and cars on the left without transponders have to move right) New Hampshire has constructed an artificial bottleneck. It was an unforced error in 2010, and, for a decade, it’s increase traffic congestion for no apparent need.

The generous take on this would be that what New Hampshire got wrong, its neighbors, Massachusetts and Maine, have improved on. That would ignore Illinois, which started building ORT gantries in 2004. Maine’s open road tolling north of Portland actually relies on a single through lane, but traffic volumes past Portland are low enough this doesn’t cause backups; its under-construction facilities in and south of Portland will not narrow the roadway through the gantries. And Massachusetts, in a fit of competence, did away with toll collection entirely, becoming one of the first legacy toll roads in the country to go to all-electronic tolling. This would also ignore NHDOT’s 20-mile road widening project now entering its 15th year of construction; while Maine argued about the Turnpike widening for decades, the actual construction was completed in only a few seasons. So I am not inclined to be generous, New Hampshire.

With COVID topping the news and traffic volumes down, of course, congestion is not an issue. But this may be a good time for New Hampshire to take the opportunity to fix a decade-old mistake. And as traffic volumes slowly increase, if nothing is done, there will be more unnecessary congestion on the New Hampshire Turnpike.