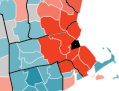

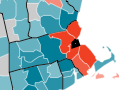

As with any city in the United States, many jobs in Boston are located away from the central business district, although those areas are not served by transit. Many jobs in Boston—in the Downtown, Back Bay, and Cambridge, are transit accessible, but many more are located in suburban office parks, far from the center of the city and with very limited transit options. There are shuttles from various transit nodes (namely Newton Highlands and Alewife) to locations along 128, mainly in Waltham. The MBTA operates limited bus service to the outer reaches of Waltham, Lexington and Needham along 128, although they are designed mainly for inbound commuting and their outbound scheduled times are likely too long for many commuters. There is limited availability and the speeds are not designed to be even close to being time-competitive with driving. However, there is ample office space which is inexpensive in comparison to downtown, and attracts all sorts of companies, even those with more urban employee bases.

There is transit service to near the Needham-Burlington employment node along 128 via the MBTA’s Riverside Line, but with a dozen suburban stops, it takes 45 minutes to reach the terminus from the core. With added shuttle times, it would create a quite-long commute. Two commuter rail lines pass through the Needham-Newton-Waltham-Lexington region, but neither has a station at 128, and their schedules are certainly not designed for reverse commuting. (It is also less desirable for park-and-ride commuters from Riverside and Woodland, as travel times to Back Bay and Downtown are not particularly speedy.) It is with these commuter lines—especially the Framingham-Worcester line—that there is potential for that to change.

There are two recent developments which make this change more feasible. One is the now-underway expansion of the

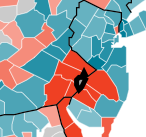

Yawkey Station (named after the long-time (and racist) Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey) near Kenmore Square in Boston. Originally built to access Fenway Park, the station received limited service in the 1990s on one side platform, but is being rebuilt to accommodate stops from all trains. The station is a short walk from Boston University’s campus and the large Longwood Medical Area, both of which have significant employment and expensive parking. In addition, the parking lots surrounding the station will be

redeveloped in to office space. With more frequent service, the station will better serve these communities.

The other new development is the (long-awaited) transfer of the Framingham-Worcester rail line from private ownership and dispatching (CSX) to the MBTA. The private dispatching has been blamed for delays which keep on-time performance on the line low, and the MBTA has been unable to increase service on the line west of Framingham because of limits in capacity. Still, the Framingham line sees ridership of nearly 20,000 (nearly 10,000 each way) a day (see this

pdf for full statistics), second only to the Providence-South Attleboro line, which sees a significant portion of its ridership board at it’s own station at Route 128.

There are three major problems with the

existing 128 station. The first is that it is not located near a major job node. There are virtually no jobs within walking distance, and no major job nodes nearby which could be reached in a short shuttle trip. In fact, east of the station, the Blue Hills take up several square miles of conservation land, which do not create many jobs. The station does serve about 2500 MBTA passengers daily and another 1000 Amtrak travelers. The second issue is that, when it was rebuilt in 2000, it was forecast to have more parking revenue that ultimately materialized, creating pitfalls for projects like it which are funded by parking revenues. Even with some MBTA parking facilites, like the Alewife, overflowing, 128 station sees hundreds of empty parking spaces every day.

These are exacerbated by the third: the 128 Station is located in the center of the least-population-dense area along 128. With the aforementioned Blue Hills on one side and relatively sparsely-populated suburbs on the other, there are few commuters who traverse several exits on 128 for the speedy trip downtown. Those coming up I-95 from Providence would likely use some of the park-and-ride stations further south, which, thanks to the high-speed nature of the line, have shorter-than-auto times to Downtown Boston (from Mansfield to Back Bay, for instance, scheduled train times average nearly 60 mph, along a much straighter line than the often-jammed highways). Commuters to the southeast use the Red Line service, and those to the north are served by the paralleling Needham and Franklin commuter lines.

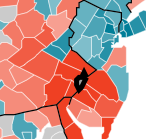

A bus/rail transfer station with commuter parking at Route 128 in Weston, near the intersection with the Turnpike, however, may prove much more fruitful to the business and commuting communities, as it would address many of the issues which the current commuting options do not. First, it would be a boon to 128-bound commuters. (A local planning group is in

early stages of discussion about this type of project.) The intersection of 128 and the Massachusetts Turnpike—which parallels the rail line—is only 11 miles from downtown Boston. Without freight traffic, rail service from Yawkey Station to this part of the line could be scheduled in 10 or 12 minutes—faster still if the grade-separated line was upgraded from a current speed limit of 60 mph. This would significantly shorten the transit time for many reverse commuters to the 128 corridor. Trains could be run at 20 minute intervals (they already are in the peak direction, so this would not require significant investment new equipment) with timed, coordinated shuttle transfers. In the future, an HOV/bus lane could speed these commuters to workplaces along the highway, and the current Riverside Line could be extended to this station. In addition to these outbound services, connecting bus service could be explored for inbound commuters with timed transfers at this station.

Such a station would not solely benefit non-traditional commuters. It would also be a boon to those Boston-bound (and, thus, not further encourage the less-than-ecologically sound movement of more jobs to the suburbs). With dedicated on- and off-ramps from 128 and the Turnpike, a garage could provide a seamless connection for park-and-ride commuters. Not only is I-90 more and more congested at rush hour (in both directions), but tolls are now $2.50 each way. Add in gas and parking costs, and $5 or $7 for parking to avoid the Turnpike would be a deal. In other words, there is already a $5 economic incentive to avoid the Turnpike, which could be a good push factor towards transit—if it were close to being time-competitive with driving.

In addition, with more-frequent off-peak service levels, such a station would serve non-commuters as well. Visitors to Boston’s many cultural and entertainment options could be enticed with an easy, comfortable ride, and one which would incur a significant cost savings over tolls, gas and parking. The MBTA already serves many customers going to Fenway Park, this could be expanded significantly.

Now, these options neglect to mention the fate of Newton’s inner stations, which are currently served by some Framingham-Worcester trains. These stations—which once had frequent commuter service—were relegated by the Turnpike to one-platform stations with no reverse commute options. Still, these stations—Auburndale, West Newton and Newtonville, average about 400 boardings per day, more than the further-out Wellesley stations which have more service. This corridor is one of the most densely-populated in Newton (moreso than the area traversed by the Green Line), and more frequent service would certainly result in higher ridership. A local-express service could be added through “The Newtons” with local trains departing the hypothetical 128 station and stopping in Auburndale, West Newton and Newtonville (and, perhaps, additional stops in Newton Corner, Brighton and Allston) towards downtown, allowing transfers from service further west and multi-directional travel in Newton and Boston.

Here, for instance, is a potential schedule for this service and assumes some line upgrades. E = express, L = local stops, NB this is a general idea, and quite condensed, but does show that clockface scheduling (except for a peak-hour express from Worcester) would be feasible. This shows inbound scheduling; outbound would be similar (with a quick transfer at Route 128) with slightly later first and last trains:

|

6a – 9a, 4p-7p |

9a – 4p, 7p-10p |

|

| Worcester |

4:30a |

|

5:30a |

:10 |

|

:20 |

|

:40 |

|

:00 |

|

11:00p |

|

| Framingham |

5:10a |

5:40a |

6:10a |

:10 |

|

:30 |

|

:50 |

|

:10 |

:40 |

11:40p |

|

|

|

L |

L |

L |

L |

|

E |

|

L |

|

L |

L |

L |

|

| 128 |

5:30a |

6:00a |

6:30a |

:10 |

:12 |

:30 |

:32 |

:50 |

:52 |

:00 |

:30 |

12:00a |

12:40a |

|

|

L |

L |

E |

E |

L |

E |

L |

E |

L |

L |

L |

L |

L |

| Yawkey |

5:50a |

6:20a |

6:40a |

:00 |

:12 |

:20 |

:32 |

:40 |

:52 |

:20 |

:40 |

12:20a |

1:00a |

| Back Bay |

5:52a |

6:22a |

6:42a |

:02 |

:14 |

:22 |

:34 |

:42 |

:55 |

:22 |

:42 |

12:22a |

1:02a |

| South Sta. |

5:55a |

6:25a |

6:45a |

:05 |

:17 |

:25 |

:37 |

:45 |

:57 |

:25 |

:45 |

12:25a |

1:05a |

Finally, there are not-insurmountable logistics towards building this type of service. The first is the ability to run two-track service between Boston and Worcester. The main current impediment to this service is through CSX’s Beacon Park Yard, which the freight railroad will mostly vacate as part of the deal with the state. This should allow the MBTA to build a second track through the area. Further west, service to the Newton stations would require platforms on both sides of the tracks, which is currently in planning stages for Auburndale (and likely relatively inexpensive for stations in West Newton and Newtonville).

The second is the ability to build a park-and-ride facility near Route 128. This, too, would present minimal issues—even for a three- or four-track station with local-express service. Why? West of Auburndale Station, the Framingham Worcester retains the four-track right-of-way which was present until the construction of the Turnpike between Back Bay and Framingham. The two tracks take up only half of the available real estate, and with shored-up embankments, there would be plenty of room for four tracks and platforms (currently, the right-of-way is 120 feet wide in this section). The office park to the north of the tracks could be connected to the station, and a parking facility could be built on the footprint of a large parking lot to the east of the offices. Furthermore, the parking facility could be connected, at rather minimal expense, to several of the ramps from 128 and the Turnpike, allowing easy access from the highways to the station. In addition, the station would allow access to the Leo J Martin Golf Course and Weston Ski Track, putting these recreational facilities within easy access of downtown Boston.

View Weston Sta. commuter rail in a larger map

Funding for this facility, and related commuter rail improvements would, of course, be a challenge. Certainly, parking revenues could help fund the parking facility, and maybe even subsidize rail operations. An additional toll surcharge could be placed on Turnpike commuters, but these drivers are already more burdened than others in Boston. Perhaps the nearby localities, which reap significant benefits from the office space in their midst, could be leaned on to help fund this type of project, which would benefit their residents and workers, and even provide some insurance to their suburban office parks against a future where higher gas prices make such car-centric facilities less economically desirable.

There is an obvious need for transit service along the Route 128 corridor. However, without smart investments in infrastructure, it will be hampered by slow service and unattractive to those who would most benefit.

(Or maybe I just want a quick train trip out to the Ski Track.)