This post has been a long time coming. A while back I asked people on Twitter if they would be interested in a post about bus bunching and short turns (answer: a resounding yes) and have been stewing on it for a while. I’ve gotten some feedback that this post is too long, so if you don’t care (and it’s quite possible that you don’t) feel free to skip and read something else. Thanks to my coworkers for looking this over and giving feedback, and the bus drivers on the service who executed the short turn.

A bit of background: in my day job, I work for the Charles River TMA. One of the programs we manage is the EZRide shuttle: a small, last-mile commuter shuttle between North Station (major transit node) and Kendall Square (major employment center). The service has been around since 2002, is mostly funded by local employers and property managers, and sort of serves as another branch of the CT buses, connecting North Station, Lechmere and Kendall. We carry about 2500 passengers per day, and are near or at capacity at peak hours (7:45 to 9:00 AM, 4:15 to 5:30 PM). Most of our ridership is comprised of Commuter Rail riders who work in Kendall. The shuttle is free to corporate members and open for a cash fare to the public.

For the purpose of this blog, I am italicizing certain transity jargon and defining them at the end of the article. Our organization contracts the route to a private operator, and we both have dispatch duties. As it breaks down, they mainly deal with driver issues (broken down buses, drivers needing time off the bus, work schedules) and we keep an eye on passenger issues (loading, bunching, headways).

Our route sometimes allows us short turns, especially when there’s bad traffic, but that successfully implementing a short turn takes a lot of know-how, and a bit of magic and luck. Some short turns are relatively easy: two buses are running back-to-back, the first bus as 33 passengers and the second bus has two. (This sort of bus bunching—here’s the best resource on that from WBEZ—is all too frequent on busy routes, even when buses run at a scheduled, even headway.) If we can empty the second bus on to the first, we can turn the first bus back to fill a gap elsewhere on the route. This only works if there is a need precipitated by traffic, but that is often the case.

Since many people have asked (okay, maybe a couple people) for a description of a short turn, here is one, with way too many words, and a bunch of maps, too. A follow-on post talks about locations where the MBTA could implement short-turns.

*****

The Route

A short turn doesn’t just happen. It comes about from a unique set of circumstances, deep knowledge of the route, traffic, passenger loads, the weather, an innate, built-up sense of what the route looks like and how it will be affected by traffic and loading in to the future. Sure, there’s some luck thrown in, but most of that is self-made: a well-executed short turn should be more science than art—it just feels like luck when it works. (And it doesn’t always work; rule number one, before you even consider a short turn, is to try to at least not make things worse.) I’ll describe a recent short turn success, and the elements that go in to it. The whole of the operation, from diagnosis of the problem to the successful implementation of the turn, took about 12 minutes—likely shorter than it will take you to read this blog post.

We have separate morning and evening routes, due to passenger loading (our reverse-peak carries MIT students) and one-way streets. The route map can be found here, and our route in Nextbus’s interface here. The route requires several routes and jogs, mostly due to one-way streets, and it’s prone to traffic, especially during construction. Our evening route can be roughly divided in to four segments, each of which takes about 15 minutes, with 16 minutes of recovery time as follows:

Inbound:

Cambridgeport to Kendall Square (moderate commuter ridership, minimal traffic delays)

Kendall Square to North Station (heavy commuter ridership, moderate to heavy traffic delays)

[12 minutes of schedule recovery time (necessary due to traffic)]

Outbound:

North Station to Kendall Square (minimal commuter ridership, moderate traffic delays, although heavy recently)

Kendall Square to Cambridge (moderate student ridership, minimal to moderate traffic delays)

[4 minutes of schedule recovery time at Cambridgeport]

*****

The Situation

On Thursday, April 9, we had some operational issues. Due to traffic signal timing problems, O’Brien highway backed up, and we experienced a 10 to 12 minute delay on our outbound route (this section carries very few passengers at this time of day, but it is necessary to get our buses from the terminal back to the start of the route). On a nice day, we might have some buses operating empty outbound through Kendall Square, but with cold rain on April 9, we had no buses which were empty and could be rerouted, so we couldn’t deadhead a bus to the terminal, or an intermediate part of the route.

The scenario was to the point where we had a 15 minute service gap. This is not good for a few reasons. First, this is double our scheduled headway is 8 minutes, so this was nearly double our schedule, even if it means that waits will only be a few minutes longer. But the issues would cascade: the first bus to pick up during this gap would fill up well before the end of the route, meaning the headway for later stops would be longer and would wind up being based on the headway of the second bus, so it would wind up being more in the 18 to 20 minute range.

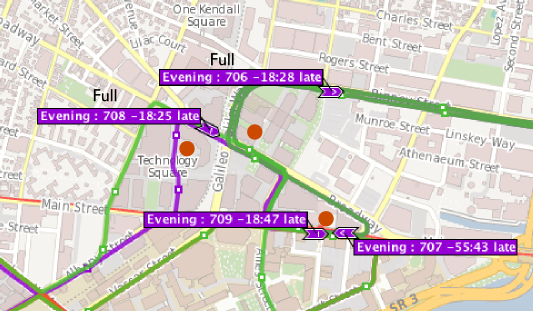

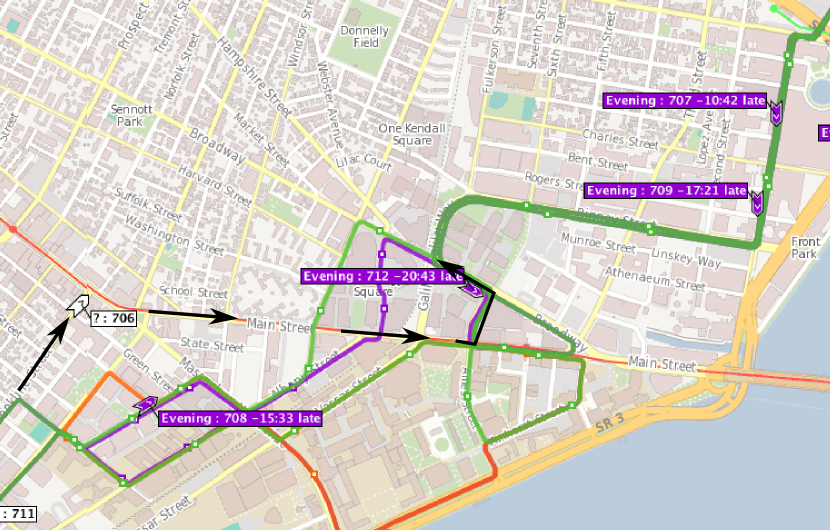

And then: the bus that was supposed to run called in with a mechanical failure. All of the sudden, 7 of our 9 buses were on the outbound route, and we were facing a 20-24 minute service gap. In other words, we were screwed. Here’s the setup:

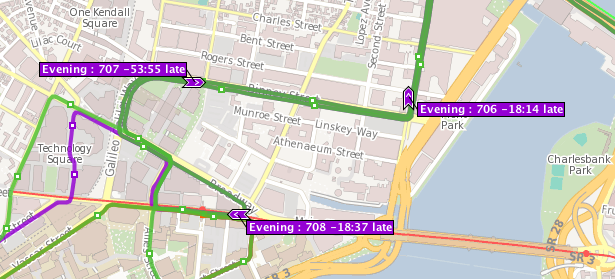

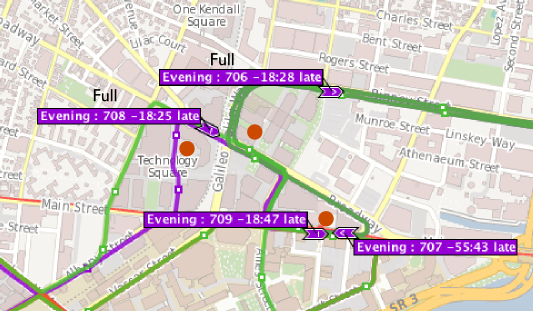

The arrows show the inbound route, and the red dots show the major passenger generators at this time of day (peak rush hour); as you can see that there are no inbound buses between the west end of the route and the eastern terminal (just off of the map) except for bus 9901, which is most of the way there. (Ignore the times “late”; we’d already had some delays to this point.) Bus 711, shown in gray, is broken down. And the driver of bus 708, at this point, got off his bus to try to diagnose the issue of 708, and due to radio traffic we were unable to tell him to get on his [goddamn] bus and drive the [goddamn] route.

So now we had a problem. 706 caught 708. We needed a bus to run the route, but expected it to fill up before it could board all the waiting passengers, especially at the three red dots. It also coincided with the peak loading time for our route, when even under normal operations buses can load to capacity and leave riders behind. We could send a double draft to run the route, but then the second bus would wind up empty behind the first bus as it boarded passengers (most of our route is too narrow to safely pass) meaning that the passengers later in the route would have a longer wait. While I was yelling at no one in particular about 708 (in our office, using curse words) my boss (who has been watching this route for more than a decade: that’s institutional memory) mentioned that we could deadhead 706. What a splendid idea—as my ire grew with 708 for attempting to fix a broken down bus and not just covering the route I hadn’t noticed this possibility. (To be fair, the driver of bus 708 probably didn’t realize the situation on the rest of the route.)

*****

The Operation, or, the Rules of the Short Turn

Rule #1 of the short turn: Don’t Make Things Worse

The first question to ask in a short turn is: will this actually make much of a difference, and might it make things worse? If you are going to move heaven and earth to get a bus somewhere 90 seconds earlier, it’s much easier to just have buses run the regular route. Unless you can solve a loading issue and a headway issue together, it’s rarely worth doing. (A service gap in a non-peak direction affects many fewer passengers than in the peak.) The second question is: will this short turn now cause more problems later? If the answer is yes (and quite often it is), you have to weigh how severe of a problem it will be, and when it will occur. Can you solve an inbound issue at 5:15 that creates an outbound service gap at 6:15? Fine, better to improve the ride for 50 riders and inconvenience a handful at a much less busy time. If you can get two people off of the second of a bunched pair and on to the first, turn the empty bus and cut the wait time for two dozen, totally worth it. But if you’re trading off a delay for three people now versus a delay for five people later, it’s not worth doing.

In this scenario, we were not going to inconvenience anyone, really, and improve service for a lot of people (and get buses better spaced in to the future). It was a no-brainer.

Rule #2 of the short turn: Know Your Route.

If you’re running a short turn, you need to know your route. You need to know where a driver can go around a block easily, or where they might get stuck in traffic (or worse: a tight corner not suited to a 40 foot bus, a frequent problem in Boston). Before you can do this kind of active dispatching, you have to know where you can safely and expediently turn a vehicle. It helps to have twenty-plus years of dispatching in the other two members of my office (I’m the new guy): they’ve been through everything. Construction detours, full road closures (the Craigie Bridge reconstruction), never-ending blizzards (okay, that was this year) and the like.

Due to the one-way nature of Kendall Square, the route does have a bizarre loop built in, which takes a couple of minutes to traverse but accesses a major stop. So one idea would be to deadhead bus 706 and have him run out of service (and preferably off-route down Main Street to Ames: nothing makes passengers angrier than seeing an empty bus drive by without stopping) and pick up at the last red dot on Broadway. If he got there expediently, he’d be able to at least pick up at that stop—and ensuing stops—and mitigate the service gap there, and take on the passenger load the first bus, 708, would not be able to pick up.

Rule #3 of the short turn: Be Invisible.

To passengers, at least. The best short turn is one where the deadheaded bus doesn’t pass any passengers waiting, where no passengers are asked to leave the vehicle, and where, except for the driver and the dispatcher, no one knows. This could also be phrased as “don’t piss off the riders” which is always a good policy: sending an empty bus past waiting passengers is a recipe for angry calls and emails. Generally, we operate under a policy of transparency with riders (we will suggest alternate transit means during especially bad traffic, for instance—it’s beyond our control but our goal is for our passengers to get where they’re going, not to boost our ridership), but we don’t feel the need to describe every piece of our operation. In the case of a short turn, we might send out a Tweet such as “Service gap inbound due to residual traffic delays and disabled bus. We will attempt to redirect service to fill this gap” usually suffice.

Rule #4: Know your Drivers

Now at this point it is worth pointing out that that you really need to know your drivers when juggling buses in this manner. Some of the drivers on our route could dispatch themselves: they have an innate idea of where every other driver is on the route, what their scheduled times are, and what their likely traffic and passenger load impacts will be. (Another recent night, two long-serving drivers basically rerouted each other and other buses, on the fly, to avoid traffic and fill route gaps far better than I could have even while staring a map of the bus GPS locations.) Other drivers are newer to the route and may not know the vagaries of Cambridge’s off-route street grid, and need a lot more guidance across the route. In this case, the driver of 708 is somewhat newer and knows the route fine, but harder to manage: we were happy that his only instructions were to run the regular route. The driver of 706 is one of our best and has been driving the route for a while; a simple instruction like “deadhead to Main Street, left on Ames, first pickup on Broadway” would be all that he’d need.

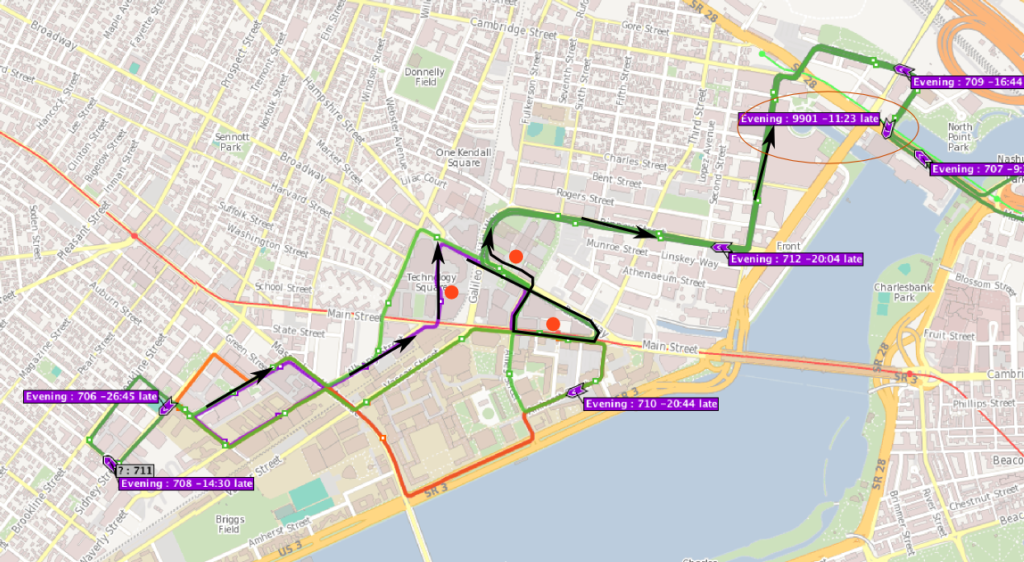

So that’s what we did. Bus 708 would run the regular route making all stops, and would likely be full at Kendall Square. (The buses we currently run are 35 foot buses with 32 seats and a stated crush load of 45, although more passengers have been known to cram aboard.) There was no point holding 706—we had another outbound bus behind him—so we sent him to do the pick-ups beyond Kendall, but to take a direct route there, leapfrogging ahead of 708 and shortening the wait at the subsequent stops (and we expected him to fill up at those stops). 708 would then run by those stops a couple minutes after 706, so would have fewer passengers to pick up.

Rule #5: Pay Attention.

But the operation isn’t over until the buses are back on the regular route, drivers know future departure times, and they have recovery built in to get back to normal. So far, everything was going according to plan, but you have to pay attention to a short turn until it’s on its way to a logical conclusion. 706 had made good time on Brookline Street and had chosen an appropriate, off-route path for his deadhead; again, had this bus passed a group of long-waiting passengers, they’d go from irked to irate. 708 was serving some moderate-ridership stops, and headed towards Technology Square, where he’d take on many more passengers.

#Protip: if two buses are coming together, take the second one. It’s unlikely to be any slower (it might actually pass the first bus) and you’re more likely to get a seat.

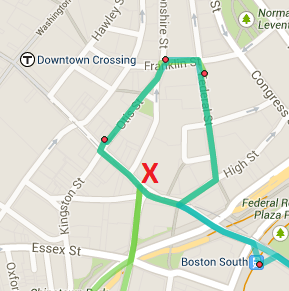

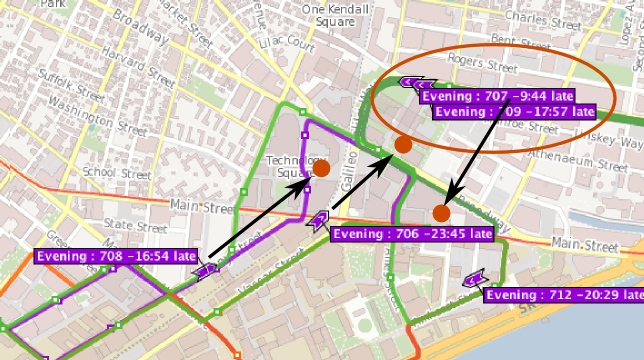

Anyway, the plan was working, rather swimmingly. And then: nirvana. See how, above, bus 707 is catching up to bus 709? While this is not a busy part of our route, but on a rainy day, there are some passengers who will take a circuitous bus ride to Kendall rather than make the walk. So while bus 709 was stopping for a rider here an there, 707 wasn’t, and he radioed in that he was behind bus 707, and was empty. Bingo. We were worried 708, upon reaching Kendall Square, would be too full for the boardings there. But 707 could conceivably balance the load between three buses as long he was slotted in before 708 reached Kendall. Each of the main passenger nodes would get its own bus, balancing the load well. If it worked. It was worth a try.

But remember: you have to know your drivers. 712 is a driver who had recently bid on to our route, and had had some issues with the route (not entirely his fault: our route flips based on the time of day—since we serve students and commuters in separate directions—and can be confusing for both riders and drivers to learn, although once familiar, it works quite well) and certainly didn’t know his way around Cambridge. In other words, if he’d been in 706 a few minutes earlier, it’s doubtful we would have sent him on the deadhead in the same way we did 706.

|

| Somehow this worked. |

But we could coach him through it. 706 and 708 had their charges, and the radio channel was clear. So the call went out. “707: take a left on Broadway, then proceed straight down Main to Third Street. Make a right turn there, and make your first pick-up at Kendall Square.” We’d have to watch him like a hawk and keep in radio contact: if he missed the turn there, at best we’d have to coach him on to Memorial Drive, and on to the outbound route (a portion of our route uses Memorial Drive, and our drivers have never missed the turn and gotten stuck under the Mass Ave overpass). At worst, we’d lose him across the Longfellow for half an hour. (Don’t laugh. This has happened.) The short turn can be dangerous.

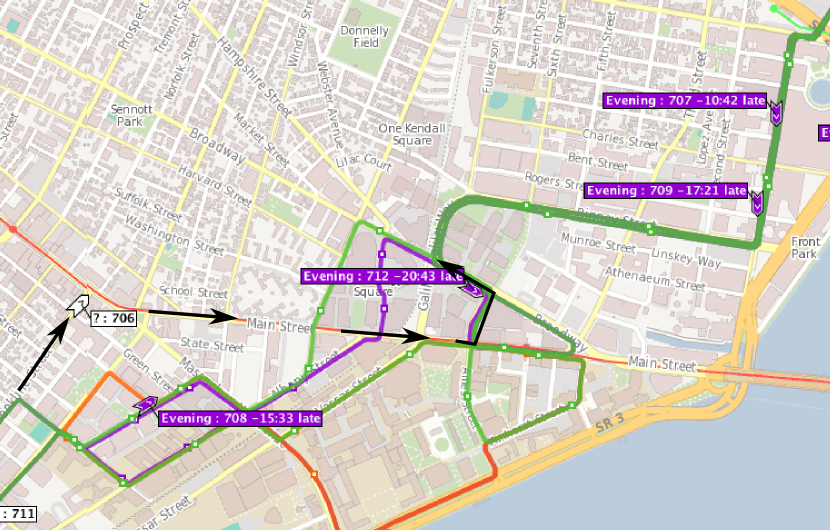

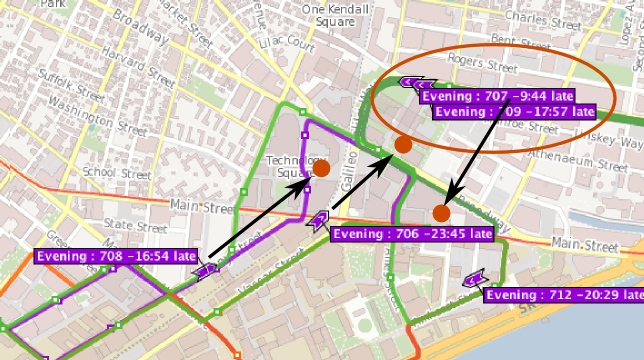

And it worked! 707 made the short turn in to Kendall and instead of following 709 on the outbound switched to the inbound. Astonishingly, we had evenly spaced the buses with about 3 minutes between each, which is particularly impressive since that meant that 706 was now 6 minutes—nearly a full headway‚ ahead of 708, who had left the route terminal behind him! And both 706 and 708 were nearly full, so bringing in 707 kept bus 708 from reaching Kendall, filling up there, and then reaching the next stops later, with more passengers to pick up, filling further, and perhaps leaving passengers behind. Much of the credit goes to the drivers, who let us know their situations (when they were empty and bunched) and were willing to jigger their routes in order to balance the load. The fact that such reroutings are not infrequent means that they’re used to being asked to do so, and that they execute the maneuver well.

Once the buses had all made their way on route, we actually had well-spaced buses. In fact, 706 and 708 were a full headway apart at this point: had we not deadheaded and short-turned they’d both be where 708 was, and we’d have cascading issues as they both ran into and then out of the terminal late. (Often, a headway issue at 6 PM can be caused by a traffic jam at 3:30.) But the pieces of the puzzle had fallen in to place, and the short turn had been executed, successfully.

This is pretty much what our map should look like in normal service. (Well, except that the buses were way off their originally scheduled runs, but if I look at the map and every bus is 20 minutes late, that means that we have even headways and just had some issue earlier on.)

As my boss said, it was ballet. It was all over in about 12 minutes. But the best part? We had the buses in numerical order: 706, 707 and 708. Boom.

*****

The Aftermath

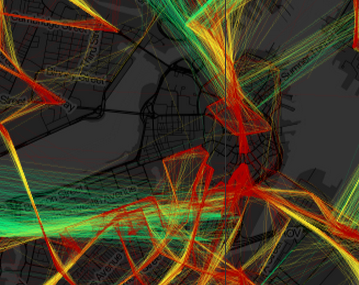

Why “art and science (but mostly art)”? It’s often suggested that computers could do this better than people, and why do transit agencies employ dispatchers, anyway, since an algorithm would do a better job? But that assumption is flawed for several reasons. First of all, unless an algorithm has nearly perfect ridership data, someone familiar with the route will have a better idea of where and when stops have heavy demand. Second, an algorithm would have to be able to not only know that a deadhead route will have less traffic at a given time than the normal route, but also communicate that route to the driver (and, frankly, I don’t find Waze and its ilk that useful at the block scale). And the algorithm would have to know which buses were full and empty: passenger counters are not perfect, but a driver can pretty quickly and easily respond to a radio call of “do you have any passengers?”

But the fundamental issue is that this type of service is dealing with people, both drivers and passengers. It’s pretty easy for a person—with some knowledge of the route—to balance out which stops to serve, and in what order, and what stops to prioritize. Maybe you’re a bit less concerned with Kendall Square because it has a shelter, so a minute or two longer there isn’t a problem. Maybe you know that given the weather one stop is more likely to be used than another because it has an overhand or an alcove for people to stand at. Maybe you know one driver is able to navigate the route faster than another (we have one of these: he drives safely and smoothly, but knows the route so well he regularly covers it faster than any other driver), while another is slower. Maybe one bus is balky and you don’t want to push it lest it break down.

Certainly you don’t want to deadhead an empty bus past a full bus shelter, or incur the wrath of customers who—even if you are doing it for the benefit of the service—would be understandably upset. And it’s also important to know your drivers, know what they are capable of, and talk them through what they need to do. Because despite all the talk of autonomous vehicles and hyperloops, right now and for quite some time to come, buses are driven by people and carry people, and despite various limitations, there are certain things where the Turing Test is still yet to be achieved.

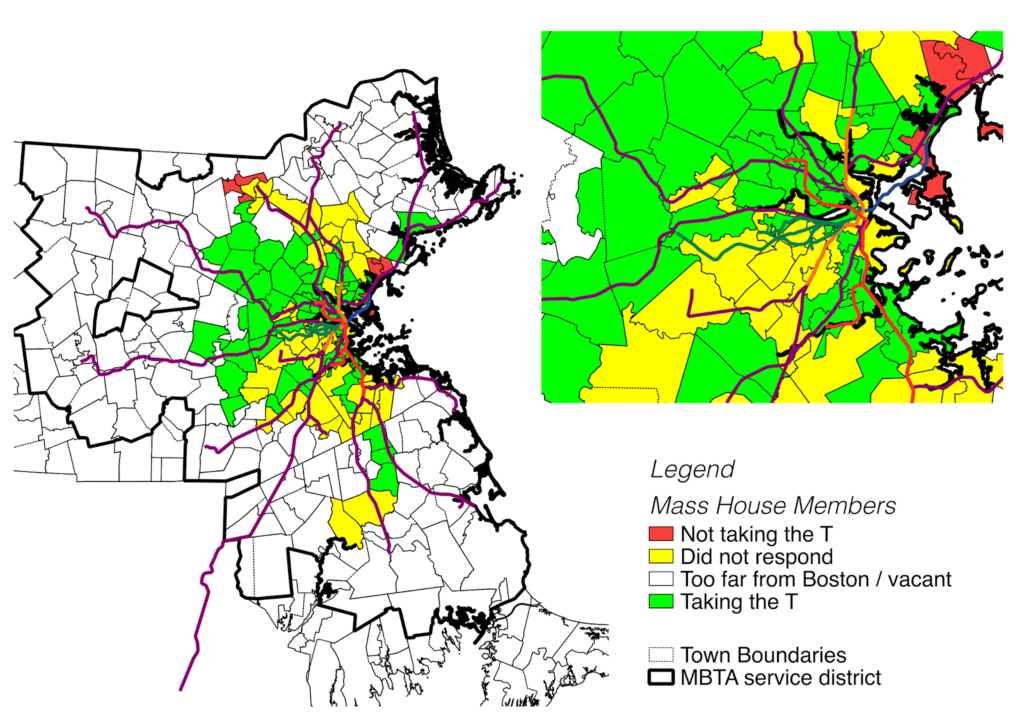

A subsequent post will discuss routes where the MBTA could potentially use short turns to mitigate the effects of bunched buses.

Glossary:

Deadhead: run an empty bus without stops, and possibly on a more direct route.

Headway: the time between buses.

Double draft: two vehicles running together; more of a train term coopted here.