I’ve gone to my fair share of meetings and written quite a bit about the Allston viaduct project.

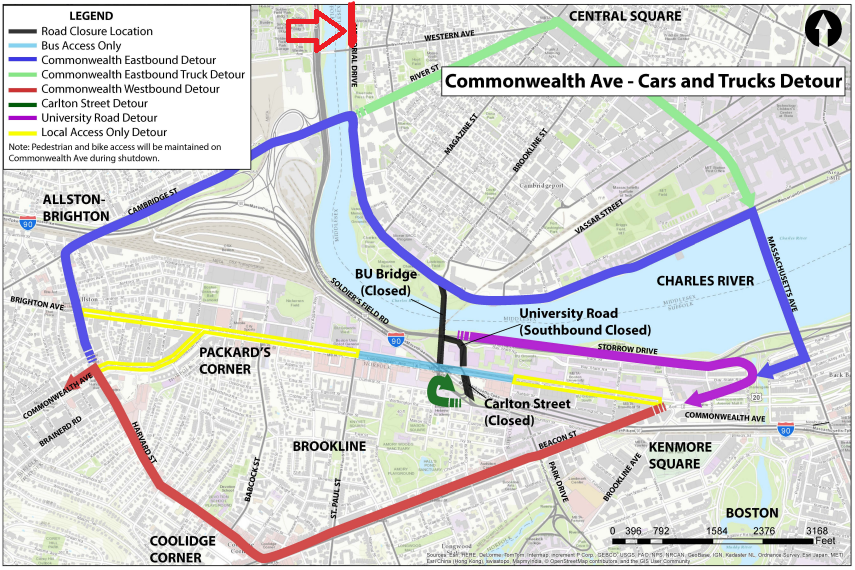

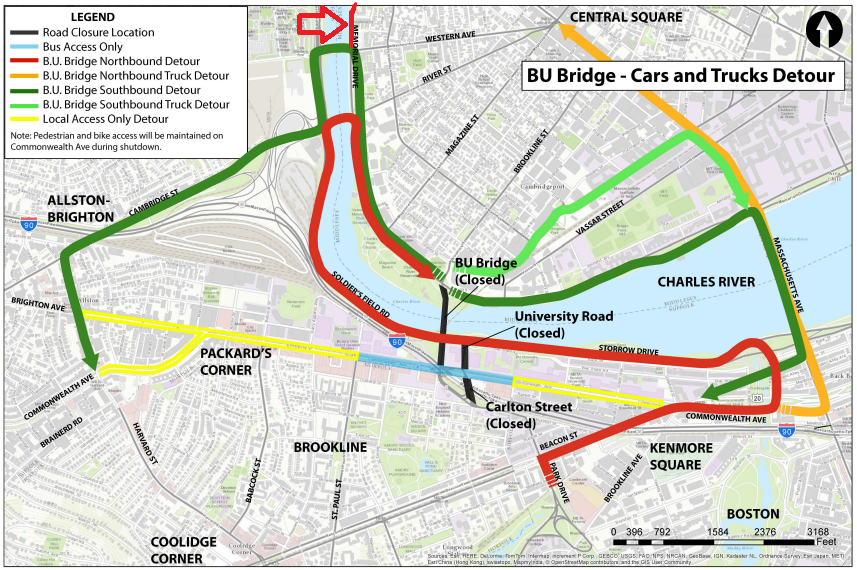

The long and short of it: $250 million for a replacement viaduct basically replicating the old one, and maybe some transit, walking and biking improvements if they can “find” the money. Everyone agrees the project has to happen: the viaduct is falling down. There are preliminary plans, and arguments over how big and wide of a viaduct to build.

But what if you didn’t build a big, wide viaduct at all? If you think outside the box (as this page has before), there’s the potential to save money. Considering how much cheaper it is to build other roads at grade, potentially lot of money. $50 million. Maybe more. The resulting highway would be safer, have better grades and sight lines, and integrate better in to potential development in Allston. It just requires a slightly change of the state of mind.

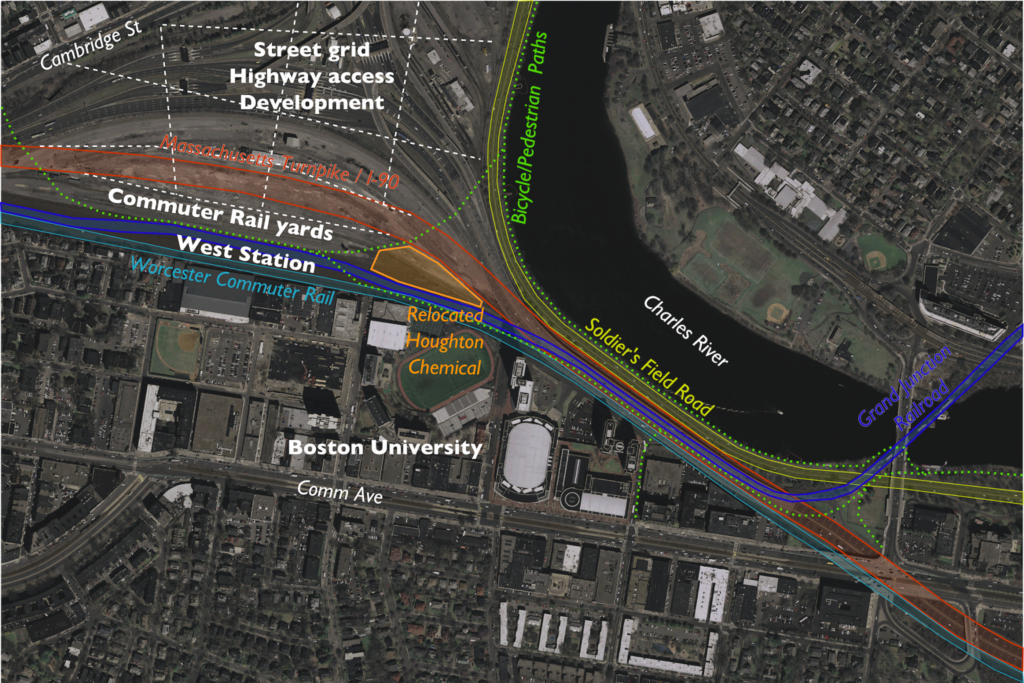

I won’t blame anyone for not realizing this earlier. I’ve been writing about this for years and it took a prompt to see if everything would fit at grade to figure it out. (The answer is you’d be about 30 feet short of lateral space to put everything at grade, and you still need to cross the Turnpike and Grand Junction.) But once you change you frame of reference, elevating the Grand Junction over the Turnpike, instead of the other way round, makes a whole lot of sense.

$250 million is a lot to spend for a mile of roadway; much of that cost is in building a high-and-wide viaduct, supports and steel and drainage, and said viaduct then costs more to maintain. This project has a lot of moving parts (bike/ped paths, Soldiers Field Road, Mass Pike, four railroad tracks going to two separate destinations) in a narrow corridor, including one (the Grand Junction branch) which has to cross another (the highway). But what if you could do it all without a hulking, expensive highway viaduct? An at-grade highway would save a lot of money. It would cost less to maintain. And it would remove the Great Wall of Allston between the river and the neighborhood.

With the state budget deficit and without increased gas taxes for infrastructure spending, we need to fully analyze projects so they are as fiscally responsible as possible. In this case, the project is necessary—the viaduct is the same age as the crumbling nearby Commonwealth Avenue bridge—but replacing a viaduct with another viaduct is far more costly than moving as much of the project as possible to grade. There is a way to do this—to build much less elevated structure—which would likely save tens of millions of dollars. We need to seriously consider it, although so far any project which does not include a large, wide road viaduct has been dismissed out of hand. That must change.

I think it comes down to priorities. With so many moving parts, there needs to be some back and forth. Certain things are immutable: you can’t get rid of the Turnpike, or the railroad. Others—what goes where, construction impacts, and the like—can be changed. So here is a rundown of priorities, roughly ranked:

- Retain Turnpike capacity at completion.

- Retain Worcester Commuter Rail at completion.

- Retain two-track right-of-way for Grand Junction at completion.

- Retain Paul Dudley White path along river.

- Provide connectivity for a future West Station

- Minimize cost.

- Maximize economic development opportunities by minimizing above-grade land use for transportation infrastructure in the Beacon Park Yards area.

- Minimize disruption to rail and road traffic during construction.

- Improve quality of life for surrounding neighborhoods.

- Add width to highway to improve emergency lanes and sight lines.

- Build a “People’s Pike” connecting the river to Allston and Boston University

- Improve parkland along the Charles River.

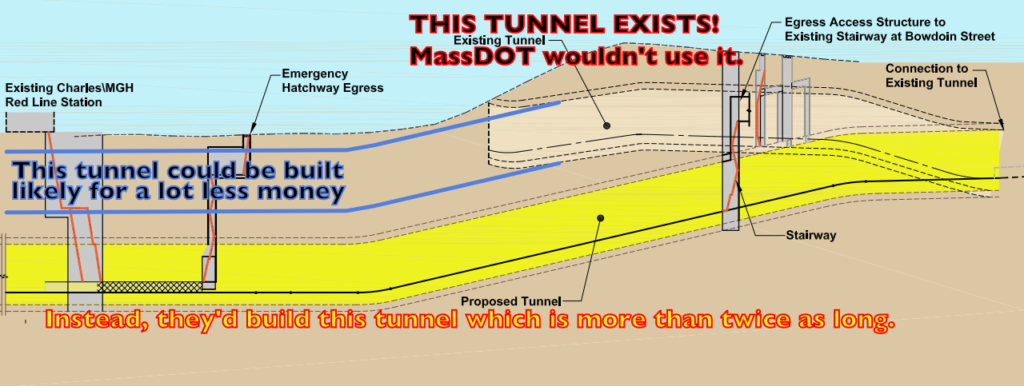

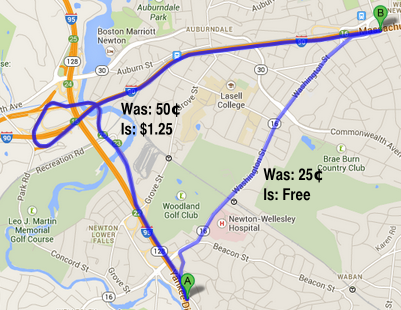

The first four items are the immutable ones. A project which fails to address them is dead on arrival; Turnpike is not going to become an Arborway-like boulevard with crosswalks and bike lanes (at least not in the next 50 years). But beyond that, it gets more interesting. The most complicated piece of the puzzle is getting the Grand Junction rail line from the south side of the Turnpike to the north side. Since 1962, it has gone underneath the roadway, and perhaps because “we’ve always done it that way,” all the plans for the future have the same scenario. Yet this requires a large, wide viaduct, and those don’t come cheap. And even setting cost aside, it turns out that it might not even be the best way to build the project anyway.

If you take a few steps back, the highway viaduct just doesn’t make sense. The Grand Junction is two railroad tracks wide, or 30 feet. The Turnpike is, at a minimum, 110 feet wide. Why not put the turnpike at ground level, and build a viaduct that is one quarter the width ? Does it make sense to put the wider, higher, larger structure above the lower, narrower one? No. Elevating the Grand Junction would be far less expensive.

What’s more, on the eastern end of the project area, the Turnpike passes underneath Commonwealth Avenue, while the Grand Junction passes over Soldiers Field Road. 1000 feet out from the narrowest part of the corridor, where one has to pass over the other, the Grand Junction line is 16 feet higher than the Turnpike. Yet the railroad slopes down and the Turnpike ramps up, as they zigzag in vertical space to attain the necessary grade separation. From a terrain standpoint, putting the Turnpike at ground level just makes sense.

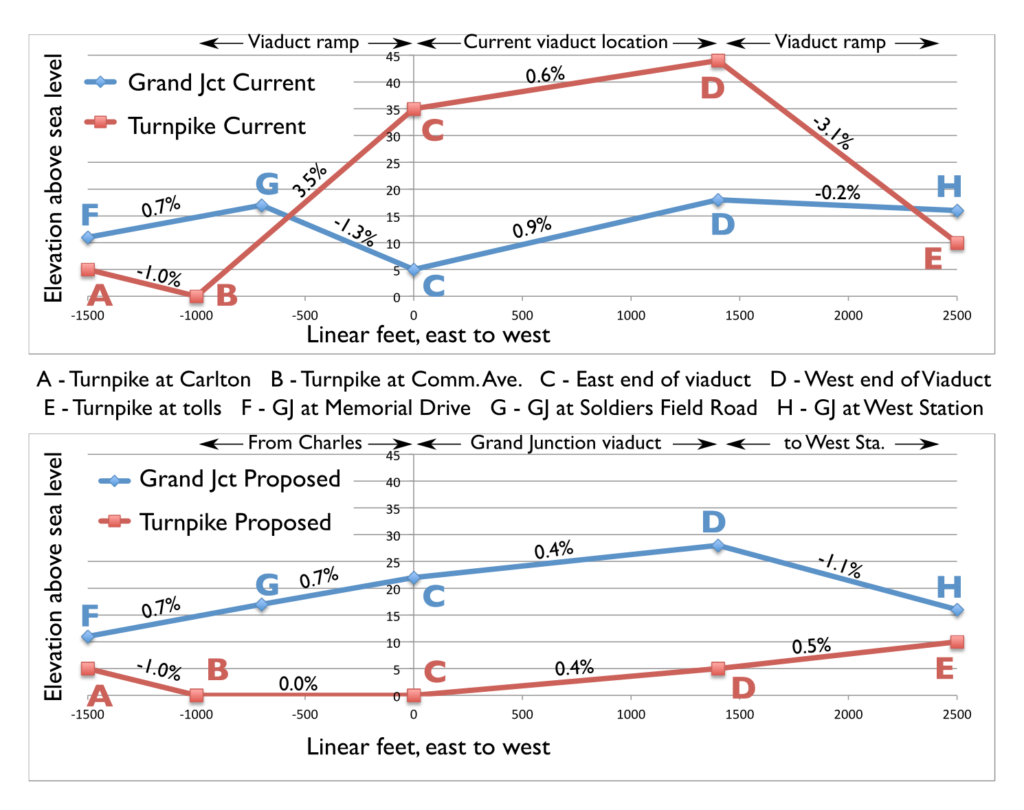

In the current setup, coming from Cambridge, the Grand Junction ascends to cross Soldier’s Field Road, and then descends sharply at a 1.3% grade to move under the viaduct. The roadway, on the other hand, ascends at a 3.5% grade to the viaduct, and then nearly as sharply at the other end to reach the toll plaza. This results in limited sight lines on the Turnpike. In the proposed Grand Junction viaduct, the ruling grade of both the road and the rail line is reduced; the rail line requires a 1.1% grade towards West Station (although this could be mitigated by slightly raising the elevation of the Worcester Line tracks), still better than the current 1.3%. And the highway has no grade steeper than 0.5% west of Comm Ave, where before it was seven times as steep, improving sight lines and safety.

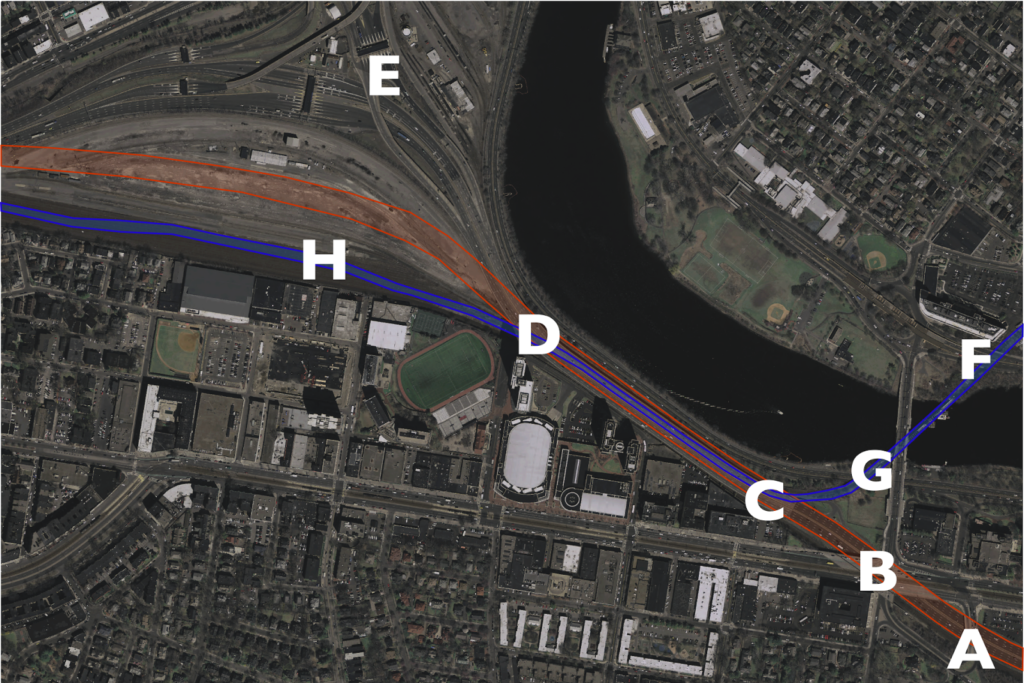

The charts below show the gradients for the current and proposed scenarios. The map below corresponds which each of the letters shown on the charts (data from MassGIS LiDAR data). Note how the Turnpike starts and ends at a lower elevation than the railroad. It makes no sense to have it resemble a rollercoaster.

What we have right now is a half-mile-long, eight-lane-wide viaduct to cross a double-track railroad right of way. It’s as if a highway were tunneled under a small stream instead of going over it on a small bridge. For whatever reason, a highway viaduct may have made sense in 1962. It doesn’t today.

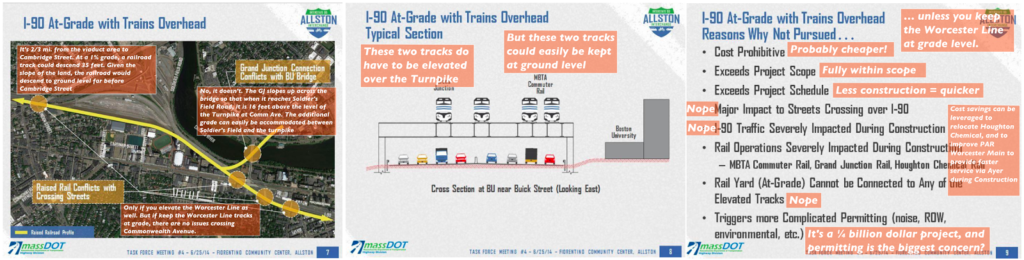

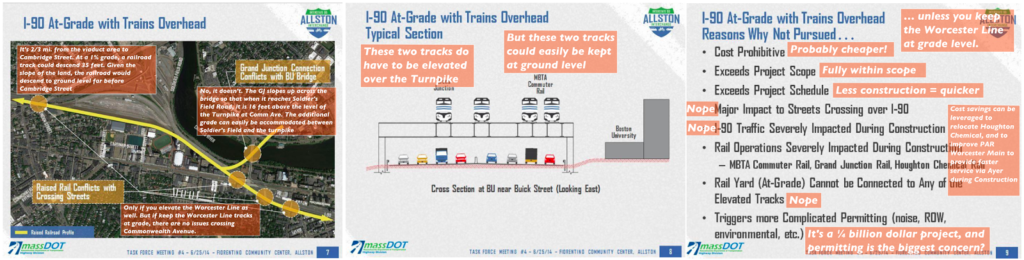

MassDOT “considered” elevating the railroad, but they dismissed it as infeasible. Why? Because they assumed that all four tracks of the railroad would have to be elevated. I don’t think it’s nefarious; I think everyone’s mindset is that the highway has to go over the railroad, because that’s how it’s always been. But the Worcester tracks stay on the same side of the highway as the whole way: they can stay at ground level; there’s no need for grade separation. The Grand Junction is much easier to elevate, and requires a much narrower structure, too. Here are three slides (from here) dismissing the overhead rail line as impossible, and my annotation on each as to why it is not the case. (Click here for full size.)

One issue is that MassDOT “requires” 135 feet of highway width for full-width shoulders. While this is “Interstate standard,” waivers can be granted for constrained areas, and much of the Turnpike (including the existing viaduct) doesn’t have any such lanes. If the highway is kept at grade, it will have much gentler grades and better sight lines. This added safety will mitigate the narrow width—and such a compromise would allow for better use of the corridor as a whole.

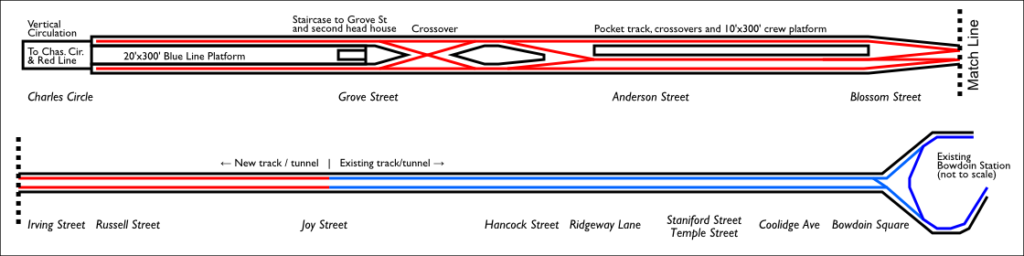

So you should kee the Grand Junction line high, and the highway low. Westbound drivers would cross under Commonwealth Avenue and then stay level. From their right, the Grand Junction line would ascend slightly—about 5 feet at a 1˚ grade—and pass on to pedestals over the center of the highway. It would continue down the center until it curved off to the left towards West Station and descended to grade. This is not a novel concept: the JFK AirTrain in New York operates in a similar manner in median of the Van Wyck Expressway. And since initial foundation work could be completed under the existing overpass early in the project, the bottoms of the pedestals and median could be pre-built with minimal impacts to traffic; less of an impact than shown here. One note: the AirTrain uses lighter vehicles than the Grand Junction, so it may require more closely-spaced supports and a somewhat thicker deck akin to what is used for other “modern” T bridges like the Eastern Route crossing of the Mystic River. (The photo on the right is of construction of the Van Wyck AirTrain, from this site.)

Which of the following is more inviting?

Since the AirTrain is elevated above cross streets as well, it’s quite a bit higher than a viaduct would be in Allston, what a cross-section would look like from the Paul Dudley White Bike Path is similar to what it looks like when it crosses a cross street. That’s a bit less obtrusive than this. Or see below:

The photos above are actually taken from approximately the same distance away. Note how much more of the sky you can see above the Van Wyck. Wouldn’t you rather have something like the image on the right?

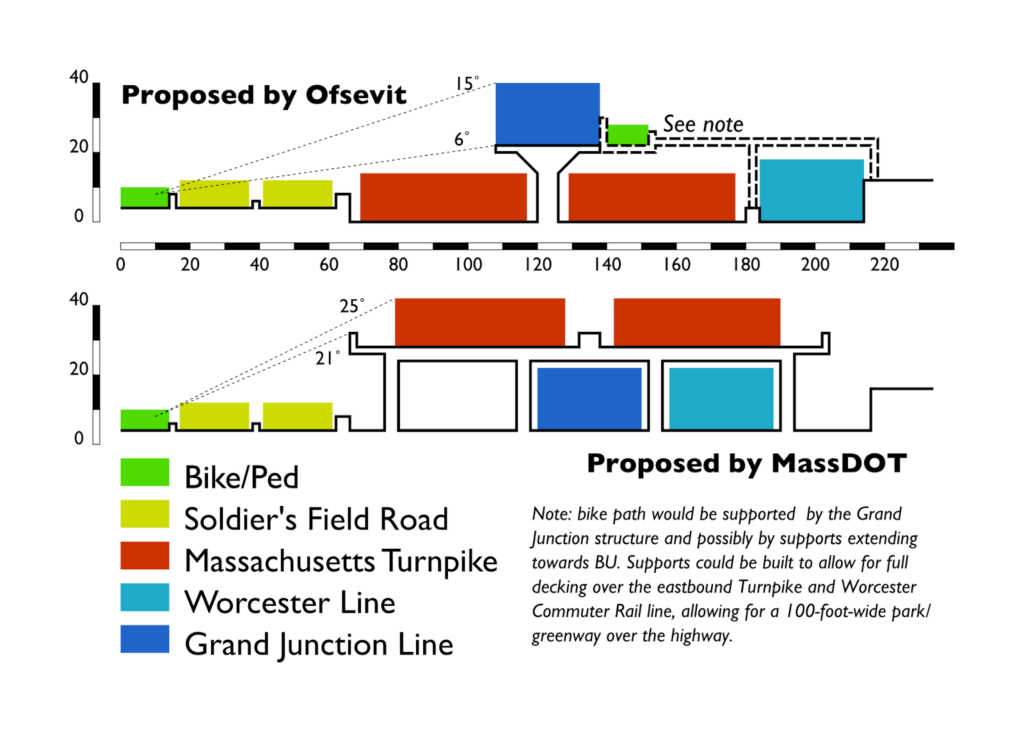

Not only is it one third the width, but it appears (and, in fact, is) lower for two reasons. In the nearby Prudential Tunnel, roads require about 14’3″ feet of clearance, trains 16’9″, so a road viaduct over a rail line is higher than the other way around. Second, trains don’t require guard rails. Put together, these add up to the top of the structure being six or seven feet lower for a rail structure. Much like how the Somerville Community Path is being built as part of the Green Line Extension, the “People’s Pike” path, it could cantilevered off the side of the Grand Junction viaduct (with additional support extending to the higher ground in—and connections to—Allston, if necessary). For an observer standing on the Paul Dudley White bike path, a rail viaduct in the median of the highway would be visible up to 6˚ in the sky, and 15˚ when a train passed over. By matching the initial grades, the highway can be lower than the Grand Junction since they don’t have to swap positions. The nearer and higher highway alternative would be visible in 20˚ of the sky, and 25˚—nearly a third of the way to vertical—when traffic is taken in to account. The smaller rail viaduct would cast many fewer shadows across the bike path and river as well.

Here is a cross section of my plans and the viaduct plan. Colors denote uses, and are scaled to the height of the users/vehicles. Scale in feet:

By elevating the Grand Junction, there is enough room for the rest of the uses:

- 14 feet for the Paul Dudley White path (an increase from 8 to 10 feet now, narrower in places)

- 24 feet for each side of Soldier’s Field Road, with a two foot median and two feet separating the bike path. This is the current width, and the road would need little modification overall.

- A four-foot barrier between Soldier’s Field Road and the Turnpike.

- 54 feet of travel space for each side of the Turnpike, enough for four twelve-foot lanes, a two foot left shoulder and a four foot right shoulder, with a six foot median where the supports for the rail line sit. Including barriers, this is 11 feet more than the current 107-foot-wide viaduct, although it is not as wide as the proposed MassDOT viaduct with full shoulders. However, by mitigating the steep grades and sight line issues, the road could be designed in this section with these narrower shoulders. With 11 foot lanes, an 8 foot shoulder could be accommodated.

- Six feet for the concrete pedestal supports for the box-girder structure for the Grand Junction rail line, which is 30 feet wide.

- 30 feet for the Worcester Line right of way, which would be relocated only slightly once the viaduct abutments are removed.

From above, it would look something like this (with just a sketch of ramps and street grid in Allston, which would built above grade):

And a focus in on the narrow viaduct area:

It would also have benefits in the Allston area. In current plans, the Turnpike viaduct has to slope gradually down through the Beacon Park Yard area. If it were at grade, it could be easily decked over, and ramps could go up to a street grid on that deck. The Grand Junction would have to descend towards West Station, but it has a much smaller footprint and would start its descent from a lower elevation, thus it would much more easily integrate in to the surrounding area.

Construction would also be much simpler, because instead of a multi-stage process where the viaduct was unbuilt and rebuilt at the same time, it would simply be unbuilt in stages, with the new roadway built on the ground below. The current staging plans call for a new, wider viaduct to be built in stages, two lanes at a time, while the old bridge is being torn down, including many temporary supports and other engineering issues. By putting roadways at the surface, you could accomplish the entire task without building any new bridging, in fewer stages (dismantling four lanes at a time instead of two), and only shoring up a few supports temporarily. It’s even possible that pedestals for the Grand Junction—which would likely be built under the current viaduct before other construction—could be used during construction to shore up the viaduct as it is dismantled.

As for the final product, rather than a 110-foot-wide, 30-foot-high viaduct, you’d have a 30-foot-wide, 24-foot-high one. The rail structure would have just 22% of the mass of the road viaduct. Road noise would be lower to the ground (with the potential for an overbuild park to cap noise all together), and the viaduct would be further from the river and from buildings at BU. And ongoing maintenance costs would be far lower. The main loss is the inability to tuck some of Soldier’s Field Road under the viaduct and create slightly more parkland in the vicinity of the viaduct. But for a cheaper project, you get a much smaller viaduct which casts fewer shadows over this area, so the bike path is a more pleasant experience.

The only major issue would be a relatively long-term closure of the Grand Junction branch, so MBTA operations and a small amount of Everett-bound freight would have to move via Ayer and Worcester. This happened recently when the Grand Junction bridge was undergoing emergency rehabilitation for several months; the biggest issue was the 10 mph speed limit on Pan Am trackage between Ayer and Worcester. (The railroad out to Worcester is Class 3 and permits 60 mph speeds, the rebuilt railroad inbound from Ayer will mostly be Class 4 with speeds of 80 mph.) With a small portion of the money saved from not building a road viaduct, that track could be upgraded to Class 2 (30 mph) trackage to save considerable time with equipment swaps and improve a freight rail trunk line as well. It would also be an opportunity to fully rebuild the Grand Junction bridge, and other portions of the corridor to Kendall Square and beyond. (One other minor issue is serving Houghton Chemical, which could be accomplished, by relocating Houghton Chemical to the other side of the highway as depicted above. In the “armpit” of the Turnpike and railroad, it would be a perfectly good site for such a use, sustain a family business in the area, and free up developable land near the river.)

Once you take a step back from the current situation and think about this, it’s obvious. It makes no sense to build a wider, higher viaduct for a roadway when you can build a narrower and lower one for the railroad. All it requires is some grading underneath the viaduct, construction that is certainly no more complex that what is being proposed. A surface roadway has a much longer lifespan and lower maintenance costs than an elevated one, and it provides a much less obtrusive—and more future-proof, as it fits in better with potential development in Allston—structure as well. It’s a better project. Best of all, given the cost differentials for projects like the Casey Overpass elimination (and McGrath and Bowker), it could probably be built for $50 to $100 million less than the viaduct, with future savings from lower maintenance costs.

That money would go a long way towards full completion of this project, mitigation steps, and ensuring the safety of other roads and bridges across the Commonwealth.