The Longfellow project is set to begin next week—signs have been flashing across the city advertising the multi-year lane closure—and at a meeting last week (documentation here), concerns were aired about traffic, gridlock, and banning bicycles from the roadway when the T is closed and buses traverse the bridge.

Wait, when the T is closed and transit riders are shunted on to a bus shuttle, were going to prohibit cyclists from crossing the bridge? When there are Hubway stations on either end? When buses will be packed with weekend travelers and trip lengths will be 10 or 20 minutes longer than usual? When taking a few people out of the system would reduce crowding and speed up trips for everyone else?

Yup.

MassDOT and the MBTA had been cagey about this, never outright saying that bikes were verboten until very recently, when their language was challenged (what does “emergency bike/bus lane” mean, anyway?) by cycling advocates.

In a recent email to stakeholders, MassHighway administrator Frank DePaola wrote:

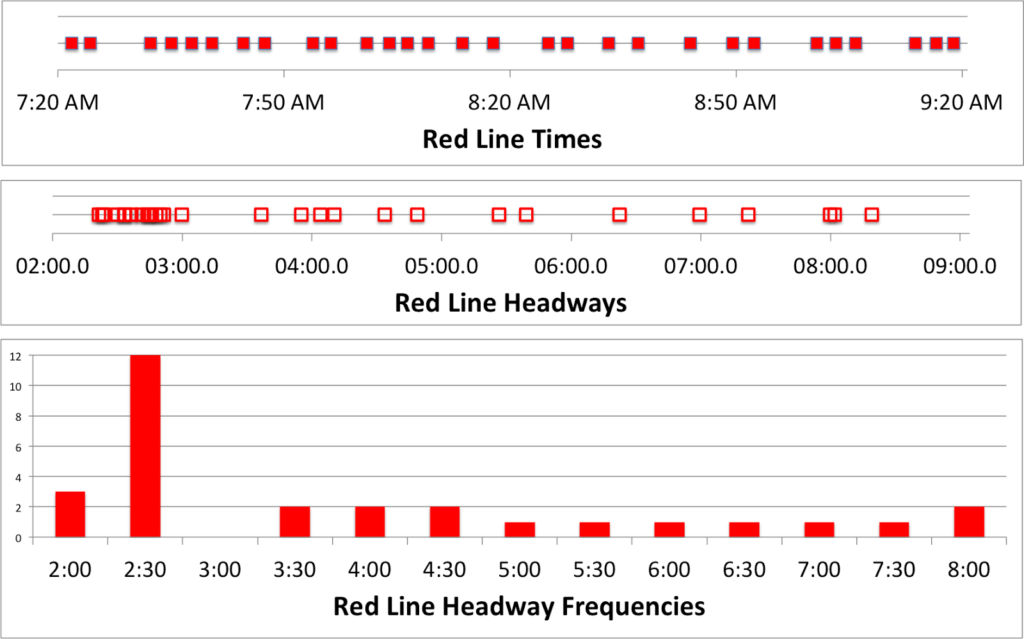

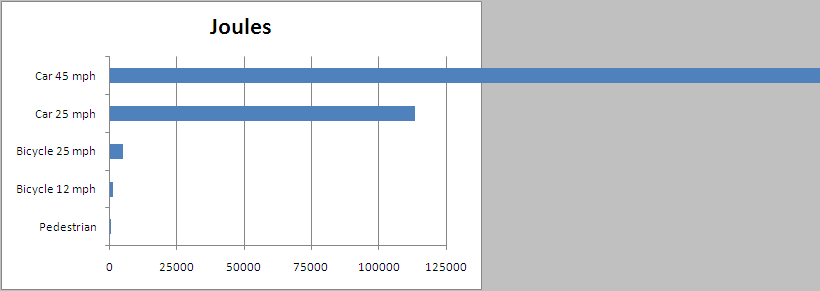

There have been recently a few tragic incidents between Busses [sic] and bicyclists one common factor has been tight clearances and the bicyclist on the right hand side of the bus. During a red line bus diversion the frequency of busses [sic] between Kendall and Park Street will be quite high the probability of an incident on the tight quarters of the bridge, especially at the approaches is too high and safety is a big concern.

Let me attempt to rephrase:

There have been multiple crashes where buses have hit cyclists when passing them. If we get rid of the bikes, we won’t have to worry about these any more.

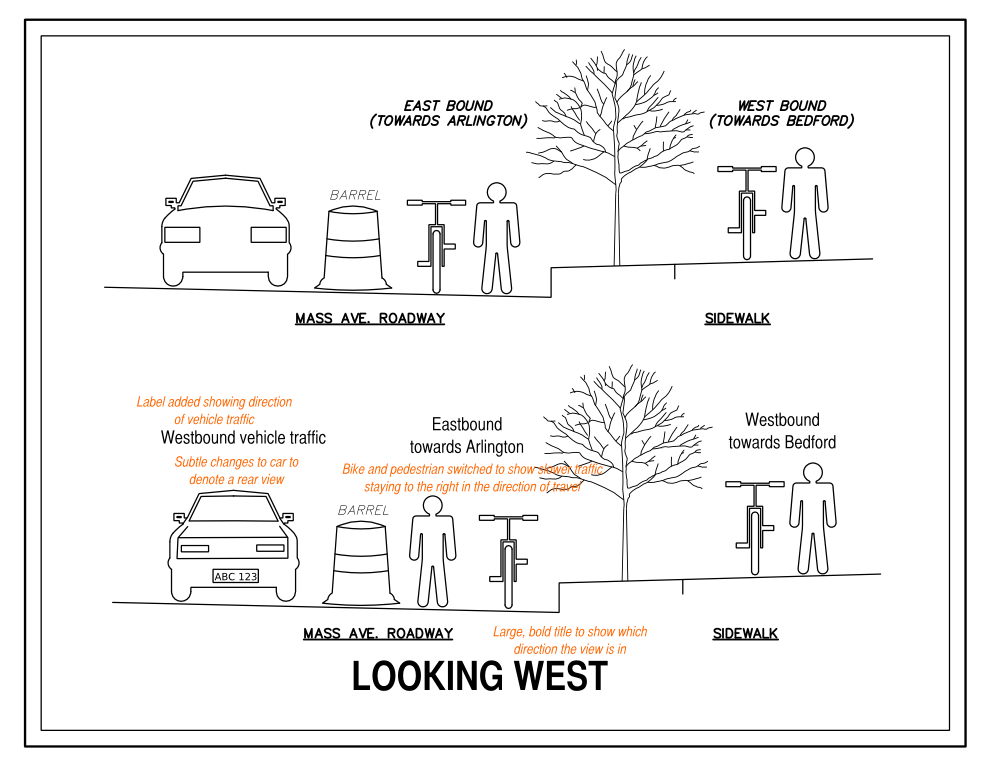

Never mind the fact that these bicycle-bus incidents have occurred with buses in normal operation, on roads with other vehicles, many distractions, and with buses pulling in and out of bus stops. The Longfellow, while narrow, won’t have any of this. There are no bus stops on the Longfellow. There will be no other cars on the Longfellow at this time. When a bus pulls out of a stop, the driver has to worry about cyclists passing on the right and cars going around on the left, while at the same time worrying about the rider running up and tapping on the door to try to get on the bus. None of this will take place on the Longfellow. Yet the default policy is to ban bikes.

While this is dismaying to the cycling community, it seems to be almost insulting to MBTA drivers. It almost says to them that the T and MassDOT don’t have faith in them to successfully pass cyclists—something they do thousands of times per day in heavy traffic—on an otherwise closed roadway. I’m sure that experienced MBTA bus drivers can drive across the Longfellow and pass cyclists at the same time.

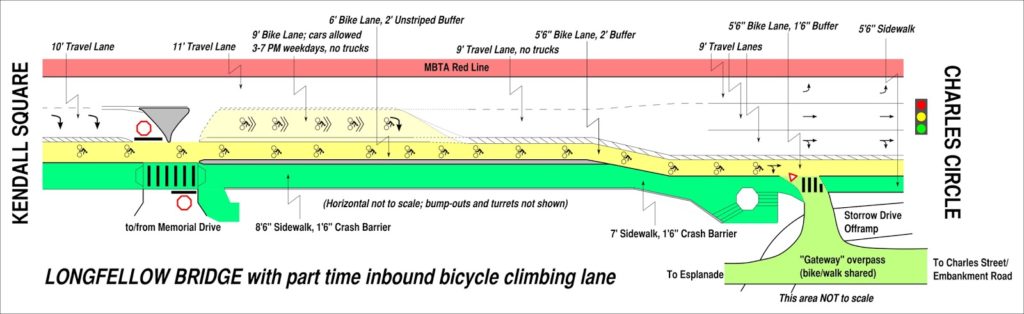

A salient issue is the pinch point at the Boston end of the bridge, where the width reduces from 29 feet to 22 feet for a 300 foot stretch. This is of concern, but could be remedied with a simple instruction to bus drivers: do not pass cyclists on this section of bridge. There is no need to erect signage to get this point across; MBTA supervisors could remind drivers of the policy before each shift crossing the bridge. (The narrowness of this portion of the bridge is another reminder that two-way vehicle traffic at any other time should be a total non-starter, especially since bicycle counts have actually increased since the new bridge configuration.)

Yes, this will result in some measurable delay for bus passengers. But these delays, I think, would be minimal. Let’s run some (estimated) numbers:

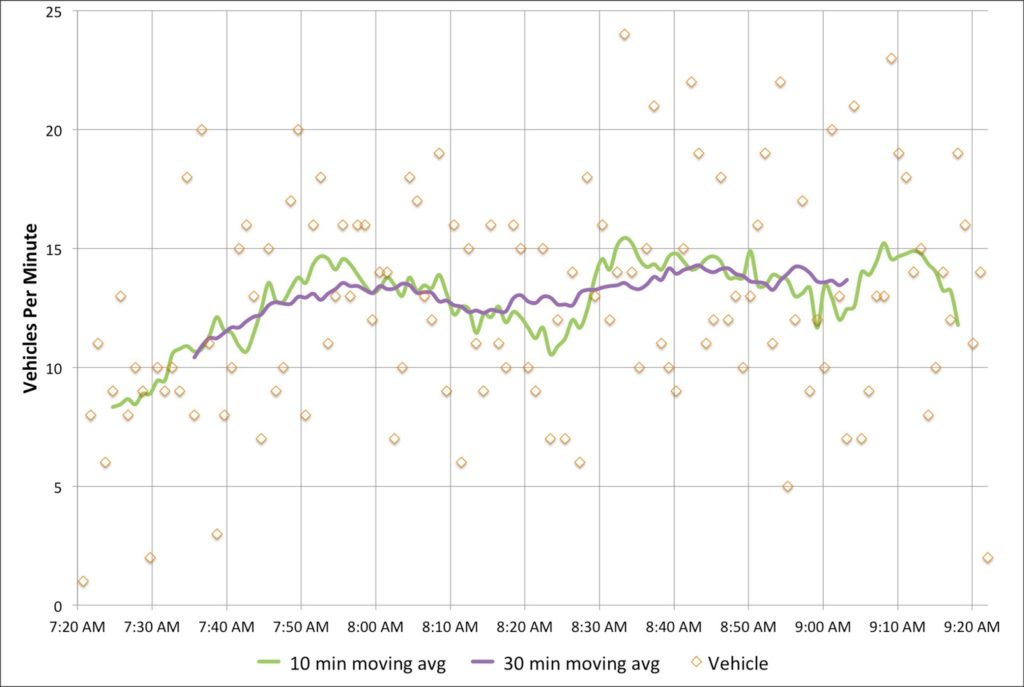

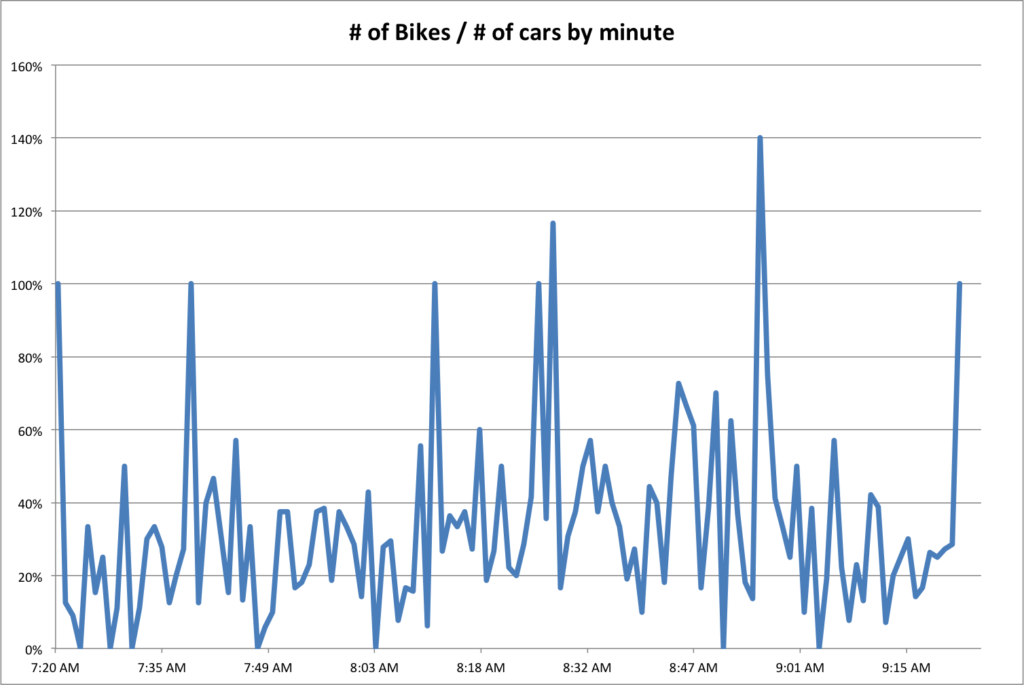

- The MBTA will have up to 15 buses on the Red Line loop to serve passengers. Assuming the route takes 15 minutes (it will likely take slightly longer) this is an average of 1 bus per minute.

- Each bus will carry 50 passengers (35-40 passengers plus standees).

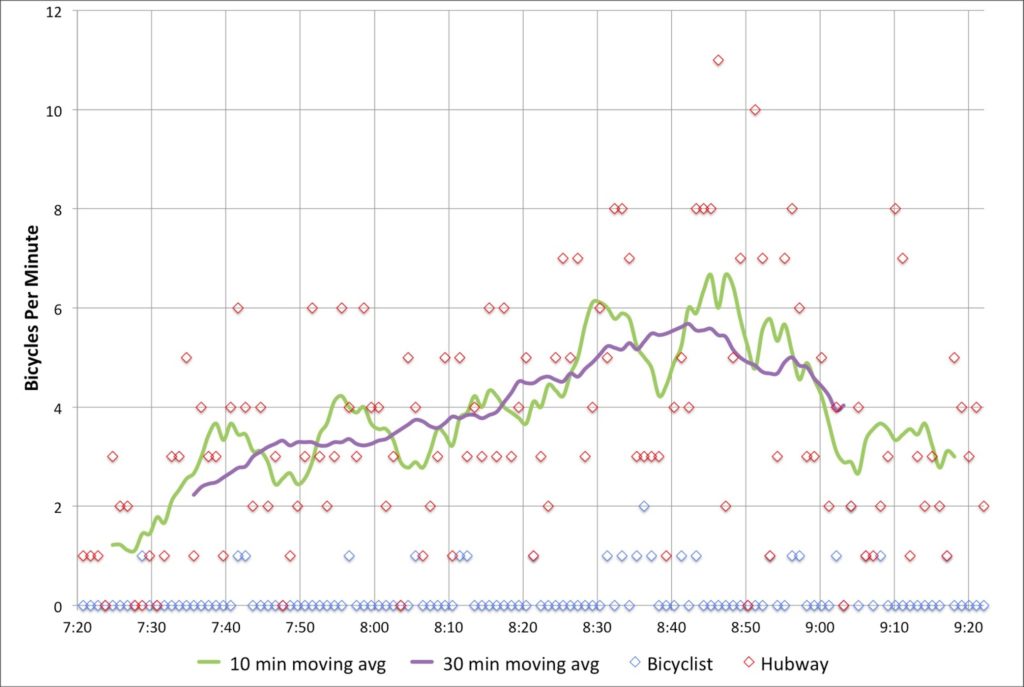

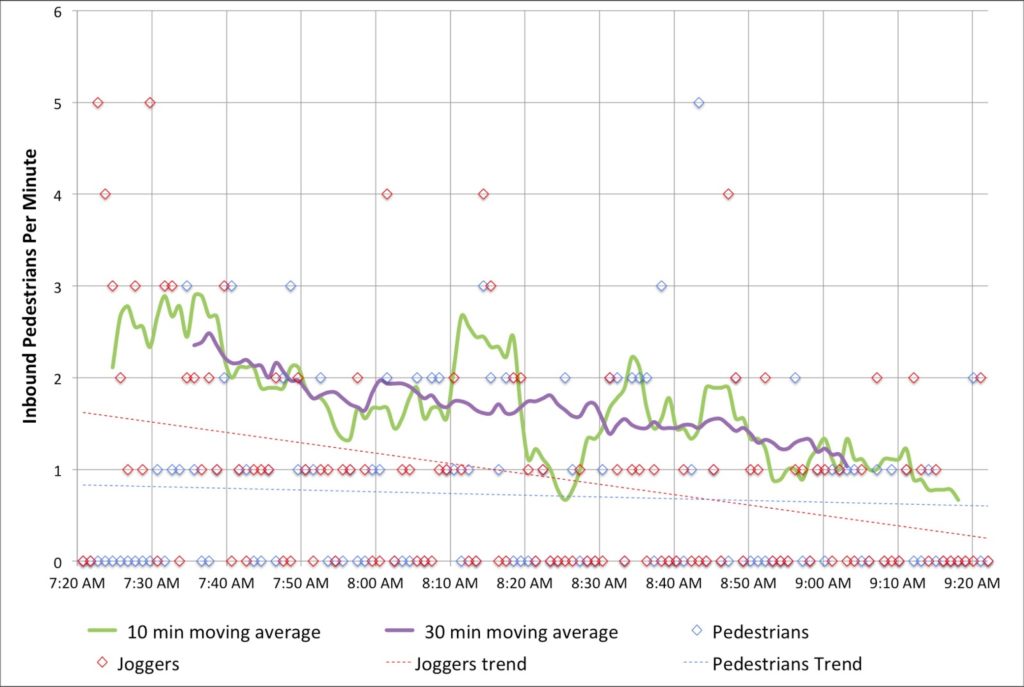

- The 2011 bicycle/pedestrian counts found an average of 30 bikes per hour in each direction crossing the Longfellow midday on weekends. While numbers may have climbed since, some cyclists will choose other routes due to the construction, so this is a fine estimate.

- Cyclists on this section will average 8 mph going towards Cambridge (uphill) and 16 mph towards Boston (downhill).

BICYCLES KEEP SINGLE FILE

This will remind cyclists that there are buses passing on the bridge. The second sign, approaching the outbound side in Boston, would read:

BICYCLES YIELD TO BUSES

This would mean that if a bicyclist and a bus approached the choke point at the same time, the bus would go ahead, and the bicyclist would then be able to navigate the narrow section before the next bus enters the bridge. This would reduce potential conflicts, as well as reducing the need for buses to pass cyclists in this narrow section.

A better policy than hoisting “no bikes” signs would be to allow bikes, and evaluate any issues which arise. This is the policy they are taking towards Mass General, TD Bank and other institutions which are insisting than closing the road to traffic will result in so much gridlock the people won’t be able to get home from sporting events or concerts (seriously) or home from the hospital (a major reason the inbound direction was selected to be kept open was to allow emergency access to MGH). If we are going to make concessions to these groups, we should do the same for cyclists who will actually help to alleviate congestion during the closure times.