Last year, the state announced that it was going to straighten the Mass Pike in Allston. Everyone agrees this is a good idea: it’s an aging structure, it includes far more grade separation than necessary, wider roadways than will be required for all-electric tolling, and a speed-limiting curve. The initial design last year left a lot to be desired: it doesn’t change much of the area, and included big, sweeping, suburban-style ramps to move vehicles at high speeds from the Turnpike to Cambridge Street, and then funnels those vehicles in to the same godforsaken intersection with River Street and Western Avenue that already exists. Apparently it will be updated, but as stated now, it is a wasted opportunity.

This area represents a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to engage major institutions and infrastructure to connect Boston in ways it has never been connected before. This page previously discussed the various related projects in the area. Harvard realized that a decade ago when they bought all the land underlying the area (MassDOT retains full easements). But there are several facets where a long-range outlook for the area would allow massive redevelopment, a new, transit-oriented housing and employment hub, and dramatic improvements to traffic flow to boot. While little of this may come to pass early on, it is important that construction that does take place does not preclude such improvements in the future.

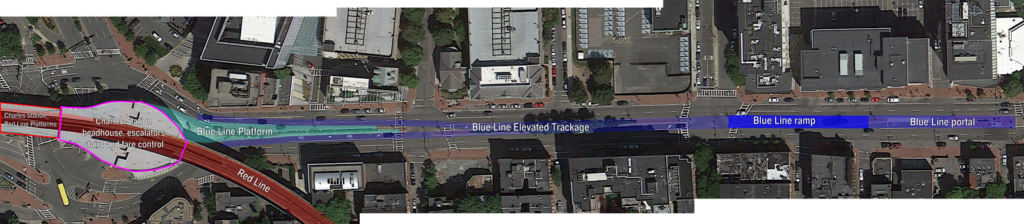

| Image from this post. Read the whole thing. |

I’m not the only one who thinks this. David Maerz has a great graphic about how Storrow Drive could merge in and out of the Turnpike, and off of the river, and it’s a huge step in the direction I’m thinking. I assume we came up with these on our own; it’s the right thinking. Hopefully we can convince the state to go in this direction as well.

The long and short of it is that while the project scope may be limited now, nothing should be constructed to preclude future development. The worst thing that could happen would be a highway engineer’s dream ramps, speeding traffic along swooping elevated highways. That may work fine 25 miles outside the city, but it would represent a lost opportunity in Allston.

Decongestion:

While traffic on the main trunk of the Turnpike (100,000 vehicles per day) flows reasonably well, the same can not be said for the ramps leading on and off (30,000 per day). (Traffic counts here) All traffic is funneled through two toll booths (or in the parlance of the Turnpike, “Plazas”) and subsequent sets of ramps. Most of it then goes through a bottleneck. Except for traffic to and from Allston, all traffic to/from Soldiers Field Road, Memorial Drive, Western and River Streets—and by extension Harvard, Central and Kendall Squares and beyond—runs through the intersection at Cambridge Street and the river. Thanks to a series of traffic lights and one-way streets, this ramp backs up to and sometimes through the toll plazas, and because of minimal throughput and merging, often creates delays of 15 minutes or longer. For traffic coming from Cambridge and Storrow Drive, there are similar delays as traffic has to run across the intersection outbound. This ties up in both directions for most busy times of the day.

In addition, these ramps create a horrid environment for cyclists and pedestrians. A relic of 1960s-era planning, Cambridge Street was built like a highway, and pedestrians and cyclists have to cross high speed ramps and then navigate an intersection with long light cycles and few, if any lane markings. Straightening the turnpike without addressing these shortcomings would be a major failure.

|

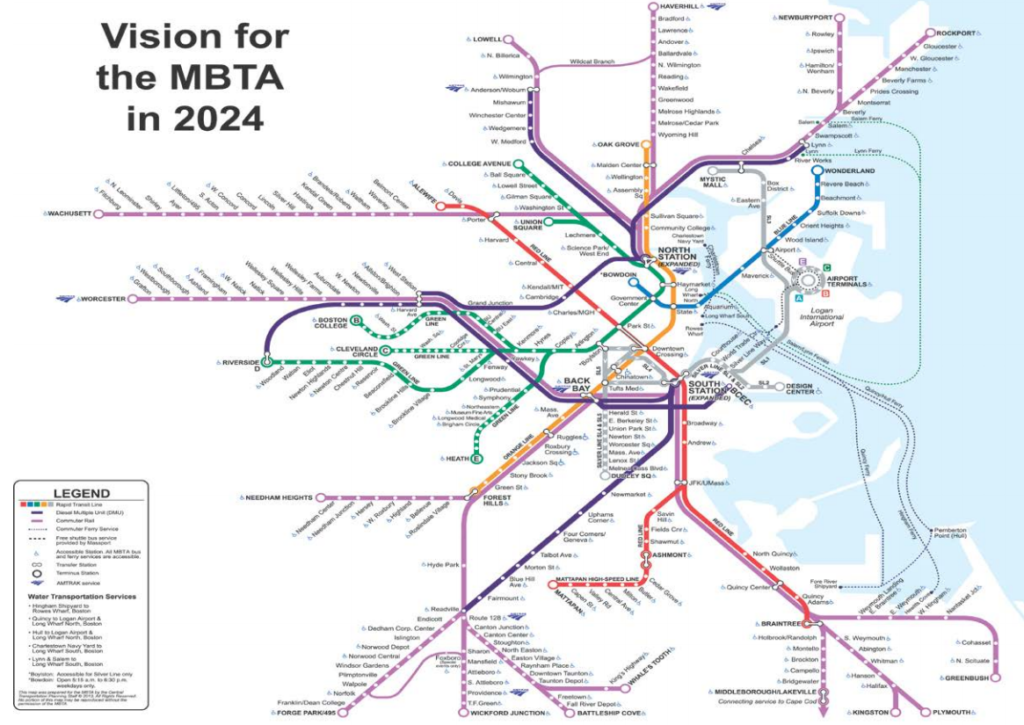

| Example of a more efficient vehicle route. |

Looking further out, however, there is ample opportunity to create additional entrances and exits from the Turnpike, and pull the congestion out of this area. For instance, a set of ramps further west in Brighton would allow traffic from Harvard Square and Fresh Pond Parkway to use the Eliot Bridge and avoid the Turnpike all together. This would remove traffic from this intersection, and reduce travel distances overall. It would also allow better highway access to the New Balance development in Allston, and several neighborhoods which border the Turnpike but do not have nearby highway access. Changes like this are not necessarily directly wihtin the project scope, but they are so intertwined that they should be analyzed along with the straightening itself.

A extension of the street grid (see next section) through the area would also help with congestion, and allow better access to the BU property bordering the rail yard.

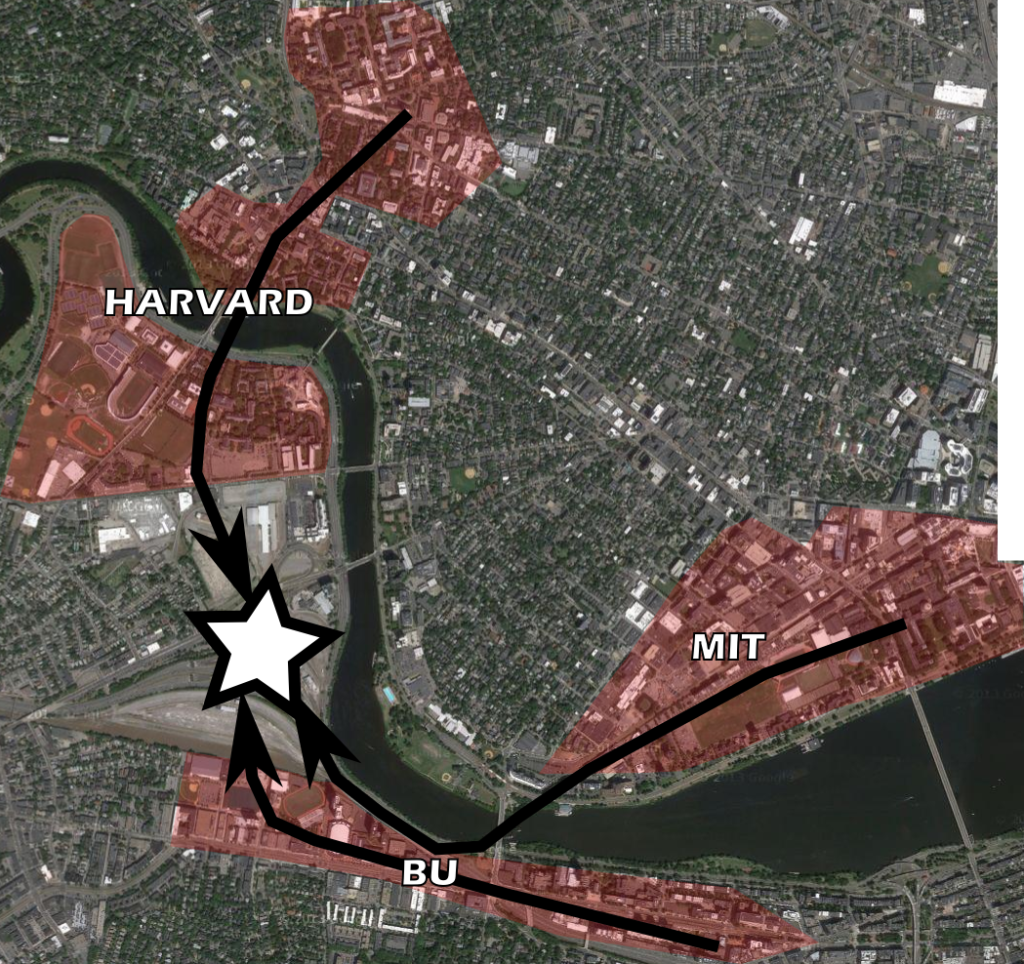

|

|

Bicycle facilities in yellow:

Potential highways in orange

Potential green space in Green

Potential street grid in white

|

Street Connectivity

Allston is currently a black hole for getting from one side of the world to the other. From Boston University to Harvard Square on a bicycle, your options are to use the BU Bridge or Harvard Avenue and the Cambridge Street overpass or a derelict pedestrian bridge. Options by foot or by vehicle are not much better. While concepts include a street grid generally along and north of Cambridge Street, there is the opportunity to connect the streets south to Boston University and Commonwealth Avenue. These would increase bicycle and pedestrian mobility as well as easing the current gridlock at the nearest crossings of the turnpike east and west of the Allston Yard, at the BU Bridge and Harvard Ave/Cambridge Streets. Entrances and exits from the Turnpike would allow for far better connections across this current hole in the system. It would also provide links between much of Boston’s bicycle network, which is one of the premises of the People’s Pike.

Development

One huge issue in Boston is a lack of affordable housing. Housing in Allston, Brighton, Cambridge and the surrounding areas is accessible to jobs by transit and to the nearby universities. The Allston plot happens to be right in the center of three schools: within a mile of BU, Harvard and MIT. While Harvard owns the land, it could provide housing for all three schools, as well as for the population in general. High-priced riverfront housing (especially if the roadways were pulled away from the river) could help to subsidize construction with less lofty views, but still a great location nearby thousands of jobs and educational facilities. Would this be a complete panacea to the housing issues in Boston? Probably not. But the land would be available to add thousands of housing units, many of them owned by colleges for student housing, which would free up some demand in nearby neighborhoods and stabilize prices. It would also provide an area which area which could be very well connected to transit for commercial development as well. By depressing as much infrastructure as possible and decking over it, a large, open area could be available for development.

One huge issue in Boston is a lack of affordable housing. Housing in Allston, Brighton, Cambridge and the surrounding areas is accessible to jobs by transit and to the nearby universities. The Allston plot happens to be right in the center of three schools: within a mile of BU, Harvard and MIT. While Harvard owns the land, it could provide housing for all three schools, as well as for the population in general. High-priced riverfront housing (especially if the roadways were pulled away from the river) could help to subsidize construction with less lofty views, but still a great location nearby thousands of jobs and educational facilities. Would this be a complete panacea to the housing issues in Boston? Probably not. But the land would be available to add thousands of housing units, many of them owned by colleges for student housing, which would free up some demand in nearby neighborhoods and stabilize prices. It would also provide an area which area which could be very well connected to transit for commercial development as well. By depressing as much infrastructure as possible and decking over it, a large, open area could be available for development.

Parkland

|

| Potential route for Soldiers Field Road away from the river and new parkland |

Right now, the Charles River is lined with roadways for five solid miles from Boston the Eliot Bridge and beyond. On the Boston side, Soldiers Field Road and Storrow Drive leave little room for bicycle and pedestrian facilities between the river and the roadway. In addition, Harvard’s Business School campus is cut off from the river by the roadway, and the advantages of a beautiful riverfront campus are denuded by a four-to-six lane highway. Harvard is obviously a major stakeholder here, but if they were amenable, the highway could be routed west of their campus and the Stadium. This would, if anything, shorten the length of the roadway, and for Harvard, instead of decking over part of Soldiers Field Road, they would have a direct link to the river.

The change would be dramatic. The current underpasses at Western, River and Harvard could be repurposed for bicyclists (a goal of the Charles River Conservancy and many bicycling and pedestrian activists) saving millions of dollars and achieving a goal for the DCR plans along the river. It would also create one of the best riverfront parks in the country. It would increase the value of real estate near the river. In the 1930s to 1960s, we paved along most of our riverfront. This would be a great opportunity to take it back.

Transit

|

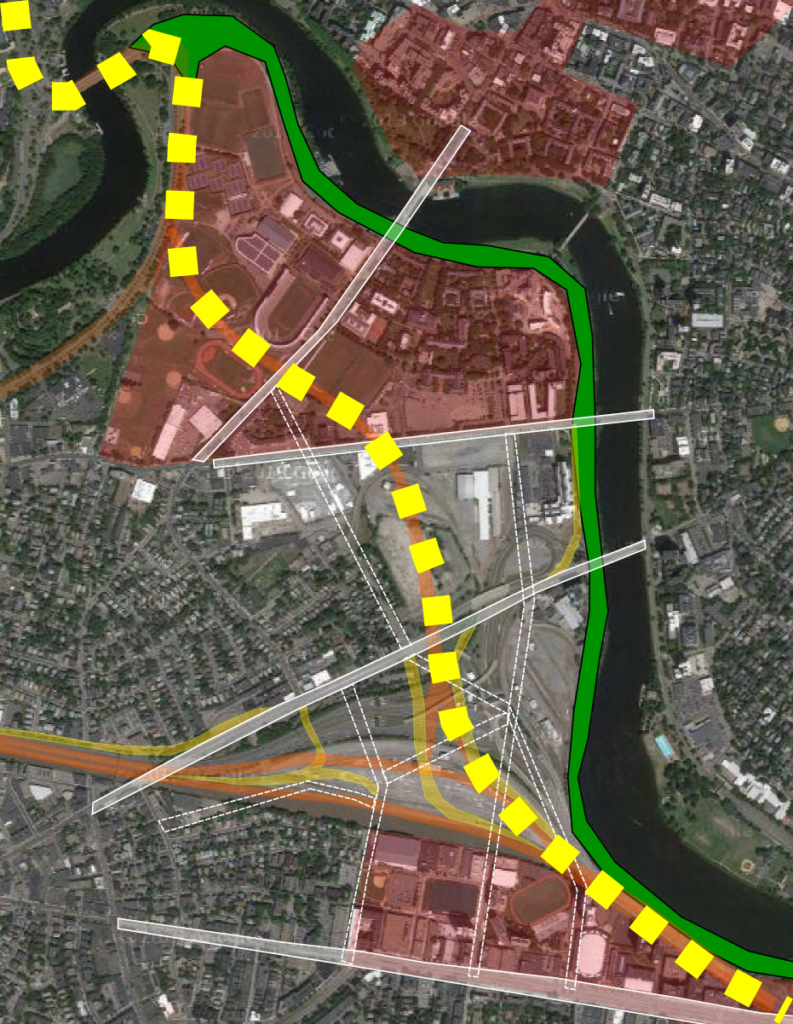

| Existing (solid) and potential (dashed) transit. New stations shown. |

Finally, this area is currently reasonably well-connected to the transit system, but it could be dramatically better connected. The state’s 10 year transit plan shows DMUs operating from a “West Station” in the Allston yard area to both North and South stations. This is a fine start. But the opportunities here are endless. Currently, there is a drastic demand for travel between Cambridge and the Fenway/Allston/Brookline/Longwood areas. The 1 and 66 are the top two bus routes the MBTA operates, and the M2 runs from Harvard to Longwood ever 5 to 10 minutes at rush hour, and frequently all day. If there were a better connection, it would be great for jobs access and congestion reduction. And buses currently skirt the Allston area, but better connections would certainly improve the situation.

So a first step would be the DMUs between Allston and the downtown terminals. Further along, the line through Kendall could be improved to allow more frequent service and transit-level service could be provided between 128 and North and South stations, serving the high-density Newton-Brighton corridor and adding more transit choices for commuters along the Turnpike, easing congestion further (and pulling off enough demand to, say, eliminate Storrow Drive west of the Bowker overpass).

In the long run, however, the Allston area provides a dramatic link between Harvard Square and Kenmore and points south. When the Red Line was relocated in the 1980s, the former yard leads to the Cabot Yards (now the Kennedy School) were maintained—the tunnels exist to this day, curving from the Red Line tracks parallel to the bus tunnel. The right-of-way is maintained through the campus (a conspicuous gap between buildings) to the river. While tunneling would be expensive, this is a transit corridor that could connect to Allston (via North Harvard Street) and then across Allston. An initial corridor could connect to the B Line on Commonwealth Avenue via the BU campus, with a connection at the “West Station.” Further along the line, it could be extended (via tunnel—expensively) through the Longwood Medical Area and Melnea Cass Boulevard to the Andrew or Columbia stations, creating the opportunity for a true Urban Ring. Since it connects with the Red Line on both ends, it could use the Red Line rolling stock (which has higher capacity than other MBTA equipment).

Obviously this is a decades-long plan, but the transitway could be at least roughed in in the Allston area (and maybe connected to the Green Line which could have a short A-Allston branch extending in to the Harvard campus) with provisions added for extensions in both directions. Again, this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity with basically a blank slate, and it’s much cheaper to build a box now than dig a tunnel under already-built infrastructure.

A lot of these steps are long in the future. However, there is no reason we should construct something now which will preclude this potential in the future.