The Boston Globe carried a story this week about Watertownies (Watertownians?) who want better MBTA bus service. Watertown is one of the furthest-in, densest communities in the Boston area with only bus service, and residents want improvements. Residents of Watertown are asking for more buses at peak hours (the T doesn’t have the vehicles to provide this), faster service (perhaps they should invest in bus lanes) and better services overall.

There is particular sentiment about improvements along the Arsenal Street corridor, which is served by the 70 bus. And the 70 bus is one of the most interesting routes in the MBTA system, and one which could certainly stand to be improved. In fact, it’s bizarre, a compilation of several separate routes, and it seems to have taken place haphazardly. The route is one of the longest in the system, and its headways are such that while it may operate on average every 15 minutes, there are frequently much longer wait times, leading to crowding, bunching and poor service levels.

The T claims to want to study the route, but can’t come up with the $75,000 to do so. We here at the Amateur Planner will provide a base analysis (for free), in hopes that it can be used to improve service on this route. One concern in the article is that “There are people waiting 40 minutes for a bus that’s supposed to run every 15 minutes.” Unfortunately, this is not an isolated occurrence based on equipment failures and traffic, but rather the fact that the 70 bus route is set up with uneven headways which mean that a bus which is supposed to come every fifteen minutes might actually have schedule gaps much longer. It’s a complicated story, but fixing the 70 bus should be a top priority for the MBTA.

I. The Route

The 70 bus was, like most bus lines in Boston, originally a streetcar line, much like the 71 and 73, which still run under the wires in Watertown. When the 70 was converted from streetcar to trackless in 1950 and from trackless to diesel ten years later, it was much like any other MTA route. It ran along an arterial roadway from an outlying town center (Watertown) to a subway station (Central), a similar distance as, say, the 71 or 57 (a car line until 1969) intersecting it in Watertown Square. But after that point, it’s fate diverged. Most other lines continued to follow the same routes they always had. The 70, however, absorbed services of the Middlesex and Boston, leading to a much longer route. As time went on it was extended to Waltham (in 1972, combining it with the M&B Waltham-Watertown line) and then to Cedarwood. The 70A routing was only merged in to the route in the late 1980s when through Waltham–Lexington service was cut, adding a third separate line to the 70/70A hodgepodge. (More on the history of this—and every other MBTA route—here.)

It now extends—depending on the terminus—10 to 14 miles from Central Square in Cambridge to nearly the Weston town line. Along the way it serves several distinct activity nodes: Central Square in Cambridge, Barry’s Corner and Western Avenue in Allston, the Arsenal Mall, Watertown Square, Central Square in Waltham, and the outlying branches. While these nodes fall in a straight line, it creates a bus route with several loading and unloading points and heavy use throughout the day. This is not a bad thing—except that the line is poorly scheduled and dispatched, so that it effectively provides far less service than it could.

II. The Schedule

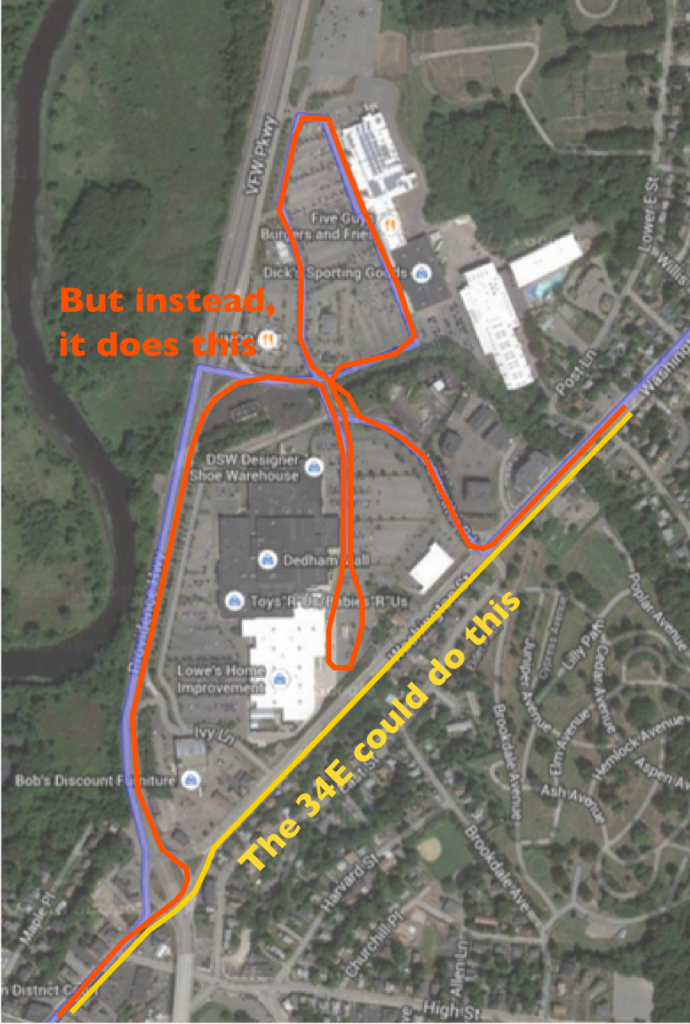

To its credit, the MBTA has very few split-terminus routes. (In many cities, split-terminal routing is the norm, as one trunk route will branch out to several destinations. Since MBTA buses generally serve as feeders to rapid transit stations, it is far less prevalent.) The 34 has short-turn service (the 34E) and the 57 has some short-turns as well. A few other routes have some variations (the 111, for example) but few have the sort of service that the 70/70A has. The 70A is particularly confusing inasmuch as the morning and afternoon routes run separate directions, to better serve commuters but to the detriment of providing an easy to understand schedule. It it almost as if the T has put all of its annoying routing eggs in one basket. Or, in this case, in one route.

The issue is that while there are two routes which are generally separately scheduled, for the bulk of the route, from Waltham to Cambridge, the operate interchangeably as one. For someone going from Waltham to Cambridge or anywhere in between, there should be no difference between a 70 and 70A. If there are four buses per hour, there should be one every fifteen minutes. For those visiting the outside of the route, the buses will be less frequent, but for the majority of the passengers, it wouldn’t matter.

Except, the route doesn’t work this way.

It seems that the 70 and 70A are two different routes superimposed on each other with little coordination. This often manifests itself in buses that depart Waltham—and therefore Watertown—at nearly the same time, followed by a gap with no buses. If you look at nearly any bus route in Boston, it will have even (or close-to-even) frequencies during rush hours. Some—the 47, for instance—may have a certain period of time with higher frequencies to meet demand. But even then, the route quickly reverts to even headways.

This is not the case with the 70 bus. If you are in Watertown Square traveling to Cambridge on the 70, there are 16 buses between 7 and 10 a.m. This should provide service every 10 to 12 minutes. Here are the actual headways (the 70As are bolded):

16 7 9 9 6 13 8 12 8 24 0 24 5 15

Anyone want to point out the problem here? The headways are completely uneven. The route is frequent enough that it should be a “just go out and wait for the bus” but it is completely hamstrung by poor scheduling. The initial 16 minute headway will carry a heavy load—nearly twice the headway of the next trip. The next trip will operate with half the load, and more quickly, catching up on the heavily-laden bus ahead of it. Later in the morning it gets worse: headways inexplicably triple from 8 minutes to 24, followed by two buses scheduled to leave Watertown at exactly the same time. (In fact, one is scheduled to overtake the other between Waltham and Watertown.) This is followed by another long service gap. Miss the two back-to-back buses, and you’re waiting nearly half an hour. This makes no sense.

And it’s not just the mornings. Midday headways are just as bizarre. When traffic is at a minimum and the route should be able to operate on schedule, headways range from 10 to 25 minutes. There are at least three buses each hour (and usually four) yet there are long service gaps—the effective headway is nearly half an hour when it could conceivably be 15 minutes. It’s obviously not easy to schedule a route with two termini, but the vagaries of the schedule mean that missing a bus may mean a wait of nearly half an hour, only to have two buses come with ten minutes of each other. And it’s not like these buses are empty, either. They serve the bustling town centers in Waltham and Watertown, and the Arsenal mall area stops regularly see ten or more passengers per trip. Yet they are subjected to a bus that comes at odd times—not one that is really reliable.

For a time during the evening rush hour, the T actually manages to dispatch an outbound bus every 10 minutes. But overall, most of the weekday schedule is a range of times which have no relation to each other, and mean that the route provides a much lower level of service than it could. (Intriguingly, Saturday service on the 70 is provided on an even 10 minute headway for much of the day; it’s a shame this schedule can’t be used on weekdays, too.)

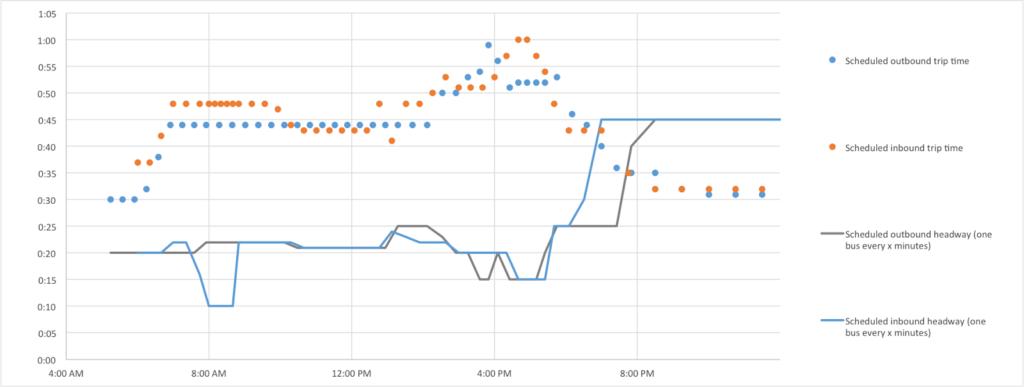

I’ve been experimenting recently with graphically displaying route schedules. It shows scheduled route times as points, and headways as lines. Time of day is on the x axis, frequency and running time on the y axis. Here, for example, is the 47 bus:

Notice that while there is a major service increase during the AM rush hour, the headway lines are generally flat during different service periods during the day.

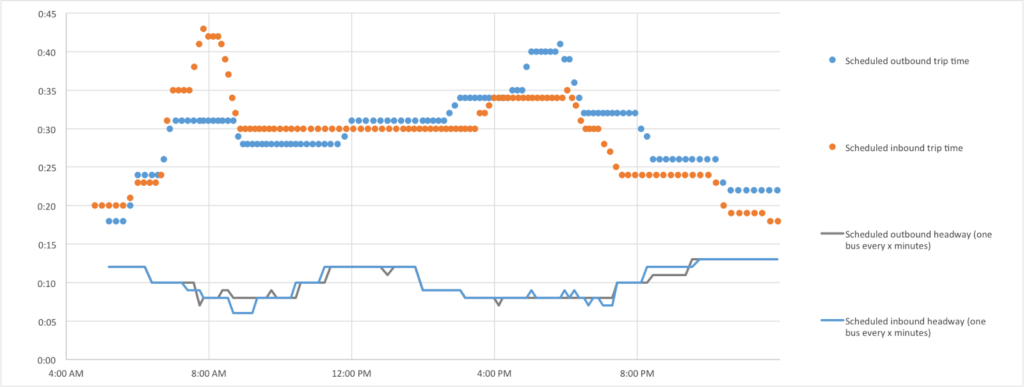

Another example is the 77 from Harvard to Arlington:

The 77 is a very frequent bus which sees 8 to 12 minute headways throughout the day. There is some minor variation at rush hours—and longer scheduled trip times at those times—but variations are minimal, and when headways change, they do so by only a couple of minutes.

Most bus routes have this sort of chart. Trip times may vary, but headways do not change drastically during the day.

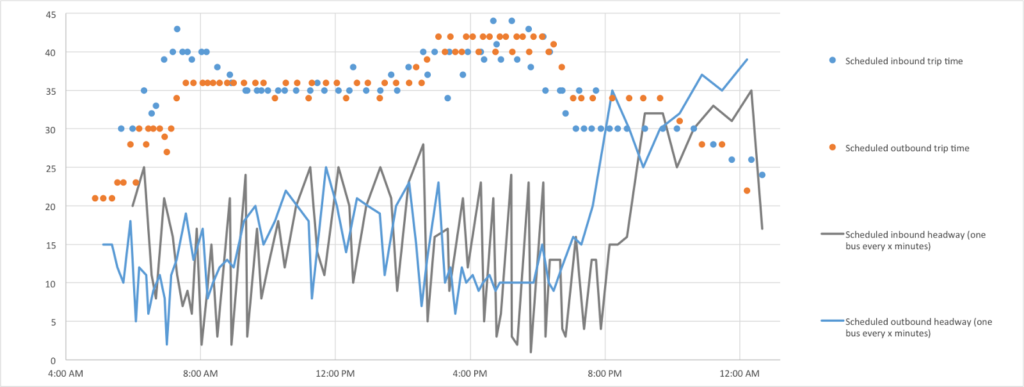

Now, here’s the 70 from Waltham to Boston:

This is chaos! Instead of a flat line, the headways bounce around uncontrollably, ranging from one or two minutes (this is from Waltham, so the 0 minute headway in Watertown Square is slightly different) up to nearly half an hour. If you go wait for a bus you may see two roll by in the span of five minutes, and then wind up waiting 25 minutes for the next. It’s only during the evening rush hour (the flat blue line) that there is any order to the schedule; even late at night headways bounce around by five minutes or more.

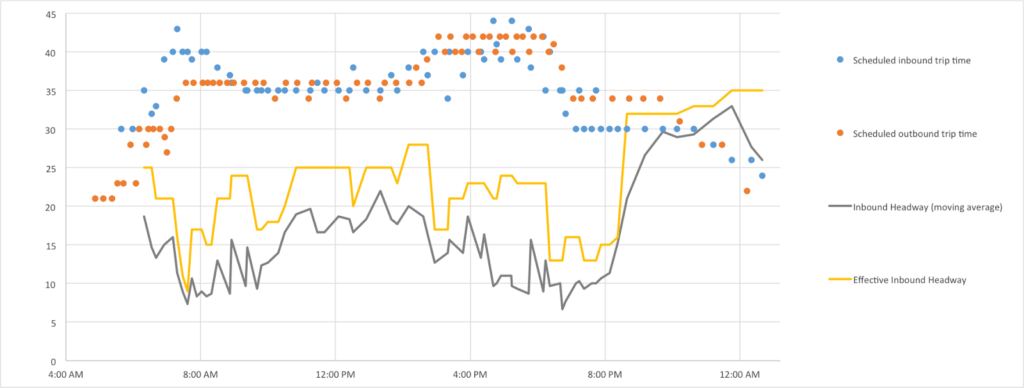

Another way to visualize these data are to look at the average headway versus the effective headway. Here, the gray line shows the moving average of three headways, which smooths out some (but not all) of the variability shown above. However, the yellow line is more important: it shows the greatest of the three headways, which is the effective headway: if you go out and wait for a bus, it’s the maximum amount of time you may wind up waiting. Here’s the inbound route:

The average headway for bus is generally about 10 minutes at rush hours, and 15 to 20 minutes during the midday, which is not unreasonable for this type of route. However the effective headway is much worse. It is more than 20 minutes for much of the day—and often eclipses 25 minutes. For most routes, the average and effective headway would be equal (or close to it). For the 70, the effective headway is sometimes double the average.

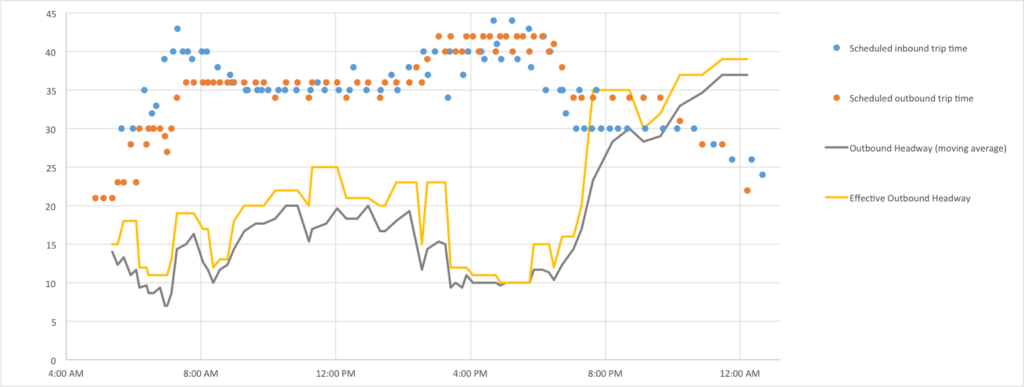

The outbound chart shows what is possible. From 4:00 to 6:00 in the afternoon, the average and effective route are nearly even—this is when buses are sent out on equal headways (and this is what the entire day would look like for most routes). However, during much of the rest of the day, the headways are less sensible. It should be possible to operate a service every 20 minutes or better, but there are often 25 minute waits for the bus, despite the fact that the two routes share an outbound departure point in Central Square.

All of this does not align with the T’s stated policy. According to the MBTA service deliver policy, “passengers using high-frequency services are generally more interested in regular, even headways.” This is the practice for most routes, but not for the 70.

III. What can be done?

As currently configured, the 70’s headways are particularly hamstrung by the 70A. Not only is it longer and less frequent than the Cedarwood route, but it’s outer terminus is not even a terminus but instead a loop (with a short layover), so the route is practically a single 25-mile-long monstrosity beginning and ending in Central Square. Without a long layover and recovery point, the route is assigned two buses midday and can’t even quite make 60 minute headways: the 10:10 departure from Cambridge doesn’t arrive back until 12:11, and that’s at a time of day with relatively little traffic!

It’s also not clear why the 70A needs to run to Cambridge. It is a compendium of three routes—the original Central–Watertown car route, the Middlesex and Boston’s Watertown–Waltham route and the Waltham portion of the M&B’s Waltham–Lexington route. This is a legacy of the 1970s—and before. It would seem to make much more sense to combine the 70A portion of the route with one of the express bus routes to downtown Boston, and run the 70 as it’s own route with even headways.

There seem to be two reasonable routes to combine the 70A with, each of which could probably provide better service with the same number of vehicles: the 556 and the 505. The 556 provides service from Waltham Highlands (just beyond the Square) to Downtown Boston at rush hours, and to Newton Corner at other times. It has an almost-identical span of service to the 70A and operates on similar headways (30 minutes at rush hours, 60 minutes midday). Instead of running all the way in to Cambridge, 70A buses could make a slight diversion to serve Waltham Highlands and then run inbound to downtown. Currently, the 70A is assigned five buses at rush hour, and the 556 four. It seems that using two of these buses to extend the 556 to North Waltham would easily accommodate 30 minute headways, freeing up three buses to supplement service on the 70. During the midday, one bus could provide an extended 556 service between North Waltham and Newton Corner (where connections are available downtown), and it might be possible to extend run 60 minute headways between downtown and North Waltham with just two buses, allowing the other to supplement service on the 70, or allow for transfers to the 70 and Commuter Rail in Waltham and express buses in Newton Corner.

The other option would be to extend the 505. The 505 is currently a rush hour-only bus, but its span of service matches that of the 70A at either end, it is only from 10 until 3 that it provides no service. The simplicity with the 505 is that it’s current terminus is in Waltham Square, so it would be a simple extension to append the 70A portion to the route. The 505 currently runs very frequently in the morning with 10 buses providing service every 8 to 9 minutes, and has 7 buses running every 15 minutes in the evening. If every third bus in the morning and every other bus in the evening were extended to North Waltham, it would provide the same level of service as the 70A, but with direct service downtown. Midday service would be more problematic, as it would require two buses to operate, and additional vehicles would be necessary to supplement the loss in service on the 70 (although the T has a surplus of buses midday, so while it would require extra service time, it would not incur new equipment needs).

Either of these solutions would allow for 10 vehicles to provide service on the 70 route at rush hour, and they could be dispatched at even intervals during that time. With recovery time, the roundtrip for the 70 at rush hour is less than 120 minutes, so with ten buses it could easily provide service every 12 minutes, and perhaps be squeezed down to every 10 minutes with faster running time on the shoulders of rush hour. If every other trip was short-turned at Waltham, 10 minute service would be possible, with service every 20 minutes to Cedarwood. And the headways would be even—no more 20 minute waits in the middle of rush hour. Transfers could be made at Waltham for 70A patrons wishing to go to Watertown or Cambridge. During the midday, similar even headways of 15 or 20 minutes could be offered—no more long waits for a crowded bus with an empty one right behind.

Over the years the 70/70A has been cobbled together from a number of routes, and this has hobbled the efficacy of the route. While the exact scheduling of the route has to take in to account many other factors (pull outs and pull ins, union rules, break times, terminal locations and the like—and as someone who recently helped create a route plan for a very short route, I can attest there is more to route planning than meets the eye), it would be hard to make it any worse than it is now. With some creative thinking, the T should be able to provide better service for everyone who takes the 70 bus without expending any more resources, and should be able to increase the effective capacity, and make it a better experience for its customers.