Shirley Leung, the Globe’s business columnist (and Olympics cheerleader) wrote a spurious article on Friday about MBTA privatization (we dissected that piece line-by-line here, and promised this longer post), where she leaned significantly on a recent study from the Pioneer Institute. Why Pioneer is taken seriously in regards to transportation is beyond me. Their numbers rarely stand up to the light of day, and when Very Serious Columnists are taking their analysis as gospel, it is a bad sign for the news media, and bad for local politics in general.

This post will look at some depth at the Pioneer Institute’s bus maintenance cost study, titled “The T’s Bus Maintenance Costs are Out of Control.” I’ve referenced the spurious “research” from the Pioneer Institute before, and mentioned this report; this is a full examination. Their assertion is that the T’s bus maintenance costs are “out of control”, some of the highest in the country, and that the T could save tens of millions of dollars a year if they just reformed how they maintain their bus fleet, asserting that their costs are twice as expensive as “peer agencies” (as defined by them, although we’ll see that their definition of “peer” is, well, suspect). There are numerous problems with this study and the numbers they use in it, to the point where their conclusions are drastically overstated and need to be fully reexamined. Since this is a very long post, I am going to break it in to two pieces: a shorter executive summary, and a larger jump deep in to the weeds of the data.

This post will discuss and dissect the following specious and disingenuous parts of the report:

- The Pioneer Institute’s faulty definition of “peer agencies”; the metric they use to select agencies is one of few which by definition varies by agency policy.

- Is “cost per revenue mile” the best metric for measuring the effectiveness of maintenance operations? Does a different number (cost per revenue hour) give us better data and better match how most bus operations account for bus costs, anyway?

- Pioneer cites Minneapolis as a close analog. But they don’t account for dramatic differences in costs of living and maintenance facilities in the two cities.

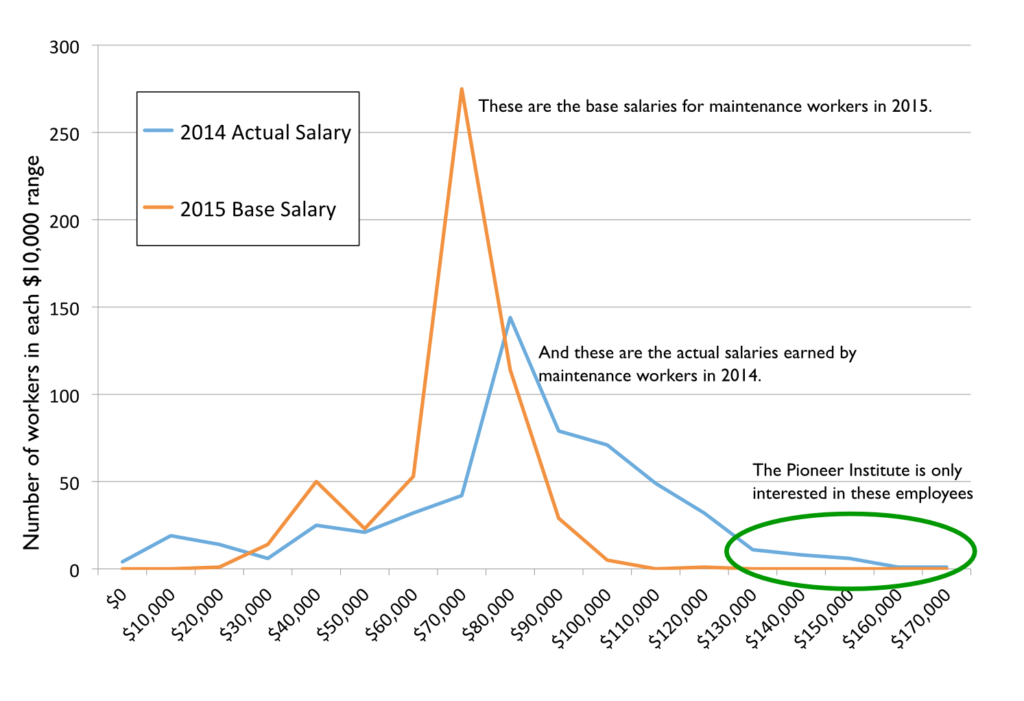

- Pioneer also digs in to the T’s salary database to pull out examples of highly-paid maintenance workers. Yet they look only at the top salaries, not at averages. This is simply hyperbole; their selective use of data serve not to inform people but to scare or anger them.

Overall, much of the supposed variation between the MBTA’s costs and other agencies that Pioneer cites are easily debunked, and they misuse data to misconstrue a problem to fit their agenda of privatization and overall cuts to transit. Instead of looking at appropriate data to try to see how the MBTA could best reign in costs, they use some of the worst data they can find to make hyperbolic statements. And when

MBTA reform panels view these data

as fact, they’ll make uninformed decisions.

In Brief: By Manipulating data, Pioneer Misrepresents Facts on the Ground

To make its case that the T’s costs are “out of control”, Pioneer first needs to find other agencies to compare the costs to. While there are many ways to use the National Transit Database to choose systems similar to the T, the Pioneer Institute takes an interesting approach. And I don’t mean interesting as in novel, I mean interesting as in suspect. The most logical idea would be to use a list of other large transit systems, but the Pioneer Institute uses miles between “failures” which the NTD explicitly points out in their definitions is subject to variation in agency policy.

By doing so, and by selecting agencies which carry one fifteenth as many passengers at MBTA buses alone (and in some cases as few as one fiftieth—or two percent—of the total number of passengers) they are really comparing apples to oranges. The T is being compared to sunbelt cities (no road salt, roads with less traffic and fewer acceleration and deceleration cycles) with many fewer passengers. These include systems which serve Palm Beach County, suburban Detroit and El Paso, for example, yet the report doesn’t compare the T to Philadelphia or Seattle, much better analogs. Comparing the T to its actual peers—other top-20 transit agencies—makes the costs go from 100% higher to just 40%. More than half of the supposed out of control costs are because of a false comparison.

The report also uses “revenue miles” while “revenue hours” would be a better metric. The T, which serves a compact, urban area, has a relatively high maintenance cost per revenue mile while its cost per revenue hour is more in line with other areas. It turns out that per hour (and many bus operation costs are per hour, not per mile) the T has some of the most efficient buses in the country, in the company of Chicago, San Francisco and New York, and far ahead of El Paso and Spokane. To put it another way: not all miles are created equally: a mile on the T will have more stops, more acceleration and more stress on the bus infrastructure, but also many more passengers.

Pioneer then cites Minneapolis as a good analog for the MBTA. While Minneapolis has a similar number of buses to the T, this analysis is somewhat fraught for a few reasons. First, Minneapolis carries only about half the bus passengers of the MBTA (and operates only a nascent rail system, so its overall transit ridership is only 20% of the T). Minneapolis also has much newer maintenance facilities (all have been built since the 1980s) as opposed to the T’s facilities, many of which date from the streetcar era. In addition, Minneapolis has the capacity to store nearly all of their vehicles indoors, a far cry from the T’s outdoor yards. Boston does have an advantage, however; it’s facilities are much more centrally-located, and it has only about half the deadhead requirements moving vehicles in and out of service that Minneapolis has, saving significant operating expenses.

Finally, Pioneer makes a hyperbolic statement about how highly-paid some T maintenance employees are, but it of course only cites the highest paid employees, and doesn’t look at any averages. The average worker is not paid in excess of $100,000; and the $70,000 maintenance salaries commanded by the skilled workers who keep the T’s rolling stock in place may be high, but are commensurate with the high cost of living. (House prices in Boston are twice what they are, for example, in Minneapolis.) The high salaries cited are due to overtime accrued (those lazy union members at it again, working 60 hour weeks), likely at times when many vehicles are in need of repairs to maintain service (the T has a relatively low spare ratio, so a problem which at another agency might be put off while a new bus is put in to service would have to be fixed at the MBTA). These cost differentials, and the fact that the MBTA has invested far less in capital facilities than Minneapolis (upgrading all of the T’s bus facilities would likely stretch beyond a billion dollars), bring the costs much closer together. Additionally, the T keeps a lower headcount (which saves on the number of benefited employees) and instead pays more overtime. This may actually save money, since for many employees the cost of benefits amounts to 30% or more of base salary, so having more employees working fewer hours may cost more.

Pioneer’s study is a textbook case of having an agenda and massaging data to best fit ones premonition. The problem is that under more scrutiny, the numbers mostly fall apart. The T’s maintenance costs are more expensive than several other large systems (although notably less than New York), and there are certainly lessons that we could learn from them. However, instead of beating the drum of the greedy unions and that privatization is the only answer, we should look at what works—and what doesn’t work—and how the T can take advantage of more efficient workplace and management practices. Relations between government and the T unions have never been warm, but specious threats based on hollow data and parroted time and again in the news media will not help the matter. And rather than trying to drive a wedge between management and the laborers, the T should give the unions a seat at the table: workers without the constant specter that their jobs may be outsourced are likely to be more productive, which may save money in the long run.

In Detail: The Numbers Behind the Curtain

What is a “Peer Agency” anyway?

In their report, the Pioneer Institute defines the “peer agencies” against which they compare the MBTA’s costs. Before we get in to exactly how they do so, below are three lists of cities (or in the case of larger statewide agencies, the city or region in which the agency operates). Two are what the Pioneer Institute used as their “peer agency” list. Which do you think is a better fit for the comparison against the T? (NB: I’ve colored systems which appear on two or more of the lists to show the amount of crossover between them.)

| List A: |

List B: |

List C: |

Washington, D.C.

Houston

Oakland

Salt Lake City

Sacramento

San Jose (VTA)

Saint Petersburg

Spokane

Baltimore (MTA)

New Jersey Transit

Orange County, Calif.

Cleveland

San Diego

Delaware Transit

Suburban Detroit

Palm Beach County

Albuquerque

Cincinnati

Jacksonville

Suburban Chicago |

Washington, D.C.

Houston

Oakland

Salt Lake City

Sacramento

San Jose (VTA)

Saint Petersburg

Spokane

Minneapolis

San Francisco

Chicago

Fort Worth

Dallas

San Bernardino

Rochester, N.Y.

Syracuse

Providence (RIPTA)

Charlotte

El Paso

Memphis |

Washington, D.C.

Houston

Oakland

Baltimore (MTA)

New Jersey Transit

Minneapolis

San Francisco

Chicago

New York City

Los Angeles

Philadelphia

Denver

Miami

Atlanta

Pittsburg

San Diego

Las Vegas

Portland

Honolulu

Seattle |

Any guesses?

List C is a list of the largest bus transit systems in the country by daily ridership. Lists A and B are the lists the Pioneer Institute uses. Does it make sense to compare the MBTA to cities like Spokane, Salt Lake City and Saint Petersburg? Or does it make more sense to use cities like Los Angeles, Philadelphia and Denver? I’d argue the latter. The Pioneer Institute, apparently, thinks the former. Note that of the Pioneer Institute’s two lists comprise 32 cities, of which just 8—25%—are among the top 20 transit systems. The MBTA, for comparison, is the 7th largest.

Before we go any further, let’s look at one piece of data for these lists:

|

Pioneer List A: |

Pioneer List B: |

Top 20 Agencies: |

| Mean Daily Ridership |

157396 |

186315 |

483682 |

| Median Daily Ridership |

100596 |

67335 |

320815 |

They’re comparing apples to oranges! The average ridership for the top 20 bus agencies is 483,000. (The T carries 405,000 daily.) The average sizes of the agencies Pioneer is comparing the MBTA to are 32% and 39% as big. Looking at the median size (more important, actually, since Pioneer does not weight their averages), the median Pioneer agency is 16-25% as big as the T. Unless there’s a very good explanation as to why they chose these agencies, it seems that they weren’t chosen for a logical reason.

So, how did Pioneer define “Peer Agency”? They looked at two metrics for vehicle maintenance: miles between failures (List A) and miles between major mechanical failures (List B). Pioneer Institute took some lower bound for the size of a bus fleet or daily ridership (somewhere in the neighborhood of 100 buses or 25,000 daily riders; they don’t define this) and sorted it by the overall miles between mechanical failures metric (which they define as “maintenance productivity performance”) from the National Transit Database (NTD) to find the “most similar” agencies.

This is problematic for two reasons. First, choosing this lower bound means that they are going to be comparing a wide variety of systems very different from the T, as seen by the list above that includes several transit systems with one tenth or fewer the daily ridership of the MBTA. Six of the agencies have ridership under one tenth of the T—40,000—another 13 come in under 100,000, or less then a quarter the size of the T. This means that nearly half of the MBTA’s “peer agencies” carry 1/4 or fewer the number of passengers daily; few of these have interconnected rail systems either. One comparison, to Palm Beach Transit, is so risible that on a Sunday, the 28 bus in Boston carries more passengers than the entire Palm Beach transit system.

This is more of an issue, because it means that Boston is being compared to many cities which have far, far less transit service. Since the MBTA carries 2/3 of its passengers by rail (New York, DC and—believe it or not—Atlanta are the only other cities in the country with more rail riders than bus riders) it means that the MBTA carries fifty times as many passengers each day than the smallest “peer” agencies in cities where transit accounts for a tiny percentage of trips. I’m going to pause and say this again: the Pioneer Institute defines a “peer agency” as one which carries 2% as many passengers daily as the MBTA. That’s a rounding error! This is like trying to draw conclusions by comparing Starbucks and an independent coffee shop. It doesn’t make any sense.

Thus, most of these systems will have buses which operate in much different conditions than the T. They have longer distances between stops, far less acceleration and deceleration, fewer passengers per bus and much less time spent with crush-load capacities which put more strain on the vehicle’s physical infrastructure. In most cases, their routes often operate through less-dense city centers and not mainly as a feeder system for subway stations like the T does, with many fewer cycles between full and empty.

Second, and perhaps even more egregious, there’s the definition of system failures (italics mine):

(List A) Other Mechanical System Failure: A failure of some other mechanical element of the revenue vehicle that, because of local agency policy, prevents the revenue vehicle from completing a scheduled revenue trip or from starting the next scheduled revenue trip even though the vehicle is physically able to continue in revenue service.

(List B) Major Mechanical System Failure: A failure of some mechanical element of the revenue vehicle that prevents the vehicle from completing a scheduled revenue trip or from starting the next scheduled revenue trip because actual movement is limited or because of safety concerns.

While most NTD numbers are rather concrete (“passenger miles traveled” or “revenue service hours”) these much more fungible based on different maintenance criteria for different agencies. Note especially that the first list is explicitly based on

local agency policy. So, not only is Pioneer choosing cities with much smaller systems, but they are compounding this issue with a metric which varies by local agency policies! What’s more, some agencies, like the Maryland Transit Agency, don’t report “other mechanical system failures”, only major ones.

It would make sense to use a variable that is well-correlated for this analysis. Here are the r-squared values for agencies with at least 25,000 daily bus passengers:

- Major failures and maintenance cost per revenue mile: 0.049

- Other failures and maintenance cost per revenue mile: 0.018

- Average weekday passengers and maintenance cost per revenue mile: 0.39

One of these things is not like the others. One of these things is correlated order of magnitude with the cost per mile than the others. And the numbers range more than one might expect: major failures range from every 1600 miles to once every 117,000 miles; and other failures, for agencies which report them, range from once every 2900 miles to once every 953,000 miles.

What might cause a bus to be removed from service in one system might not in another. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it makes it very suspect to use these numbers as a basis for further analysis, especially when better numbers certainly exist. It would make much more sense to choose the cities in the top 20 to compare to the MBTA. The problem is that such a list wouldn’t have supported the Pioneer Institute’s “conclusions” nearly as strongly.

Pioneer is measuring the “productivity” of a bus maintenance shop by the frequency with which the buses broke down without looking at any other data. This is like measuring the “productivity” of a doctor by the frequency with which his or her patients die. Which is all well and good—some doctors are actually more productive than others—except that a cardiologist is going to have more patients die than an optometrist, a gerontologist is going to have more patients die than a pediatrician, and a doctor that works in a high smoking state like Kentucky is going to have more people die than someone working in Utah. If you’re not correcting for the age of the vehicle, variations in the kinds of vehicles used, and variations in the duty cycle, you’re going to come to some screwy conclusions.

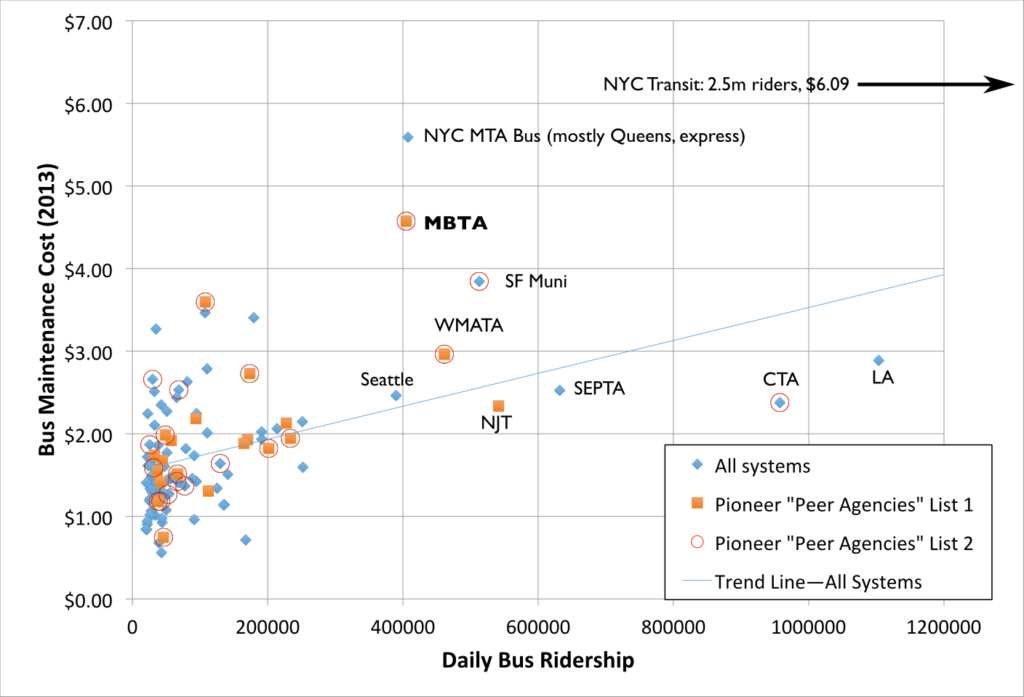

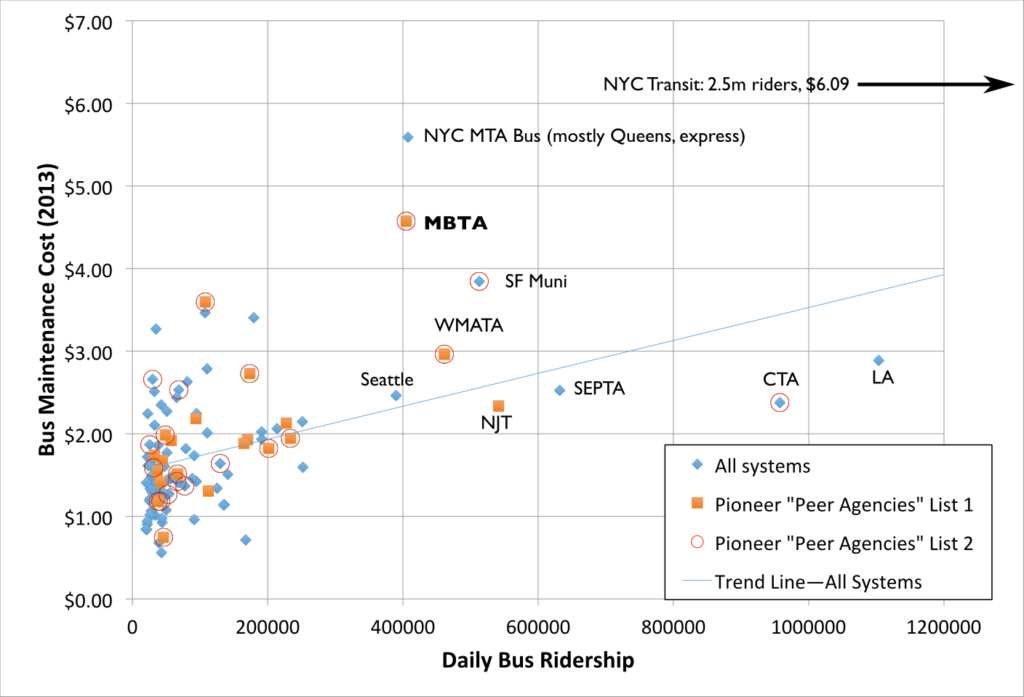

I like charts, so here is one. It shows transit systems with more than 20,000 riders. Note how the Pioneer Institute’s “peer agencies” are mostly clustered in systems with much lower ridership than the MBTA. I threw in a best fit line for fun, and, yes, larger agencies have higher maintenance costs. Which is not surprising.

I like charts, so here is one. It shows transit systems with more than 20,000 riders. Note how the Pioneer Institute’s “peer agencies” are mostly clustered in systems with much lower ridership than the MBTA. I threw in a best fit line for fun, and, yes, larger agencies have higher maintenance costs. Which is not surprising.

In any case, it comes down to a sort of Occam’s Razor question: the obvious definition of “peer agency” would be “other large transit systems.” Since that was not the metric used, we need to look in to why it was not. If there’s no good answer why it wasn’t—and there isn’t—then it certainly seems like the reason Pioneer used these criteria is to try to prop up their preconceived conclusion, rather than to make an honest argument.

I’ve only compiled the 2013 data (why? because I am doing this evenings and weekends and I don’t have a paid team of fellows and researchers funded by right-wing climate change deniers to go back through several years), but note the following:

|

Pioneer List A: |

Pioneer List B: |

Top 20 Agencies: |

MBTA maintenance

cost % of average |

208% |

192% |

153% |

In other words, just by choosing a more representative data set, we’ve explained away half of the discrepancy between the T and other agencies.

But, wait, there’s more. Let’s say you only looked at the small group of agencies clustered near the T. There’s a big (50% increase) gap between Denver at 250,000, and Seattle, at 391,000, and another 50% gap between SEPTA and the CTA. If we compare Boston to Seattle, New Jersey, San Francisco, New York MTA Bus division and Philadelphia, the T averages just 140% of those other agencies, barely one third of the difference Pioneer’s “data” show. That seems like a much more representative sample than, say, Salt Lake, Sacramento, San Jose, Saint Petersburg and Spokane. I would wonder if the Pioneer Institute would deign to offer an explanation as to why they chose “peer agencies” in the manner that they did.

As I see it, there are three. One is that they randomly picked the metric to categorize this, and somehow stumbled on to the worst one they could since it’s really the only NTD data which varies by agency. I doubt this based on the Occam’s Razor principle that if you asked a student in a first year transportation statistics class what to use, they’d be hard-pressed to come up with what Pioneer did. The second is that someone doing research at Pioneer just isn’t that bright, and that’s a possibility. But the third is more nefarious: they came in to the study with a question they had a preconceived answer for, and then found the snippet of data which best supported their thesis. The problem is, well, the data.

Are all miles created equally?

Once the Pioneer Institute chose the wrong systems to compare the T to, they then chose to compare those systems based on a metric of “maintenance cost per mile.” On its face, this seems like a good analysis, and it’s not bad, but it ignores the issue that not every mile is created equally. For instance, which causes more wear and tear on a bus: a mile in stop-and-go traffic with a stop every 800 feet and 60 passengers on the bus, or a mile at 35 mph with two traffic lights and two passenger stops carrying 20 or 30 passengers?

Here’s another way to think about it: which is more stressful for your car? Driving with four passengers, a full trunk in stop-and-go traffic or a highway trip? The former is what buses in major cities are put through on a daily basis. But in many of the “peer systems” on the lists above, buses ply faster suburban arterials in much less dense areas. This means that they make fewer stops, and at those stops they pick up fewer people. That means less wear and tear on door mechanisms, air bags, transmissions, tires and even the vehicle frame. Wear and tear on a bus depends on its operational environment.

A better metric—one that accounts more for operational differences—would be maintenance cost per revenue hour. Bus costs are usually measured in hours (operators are paid by the hour, not the mile) and calculating revenue hours is a better way to account for different operating environments. For instance, a bus in City A might average 10 miles per hour and a bus in City B might average 15 mph. However the bus in City A might have more passengers over the course of that hour, more openings and closings of the doors, and a heavier average load. Cost per hour lets us better account for this.

So how does the T stack up on this basis? It’s still quite high, around $45.00, while the top 20 cities average to $30 and the Pioneer “peers” come out at $25. Instead of being 200% of its peers, the T is “only” 180%. So by using this metric, the T is still underperforming. However, there are more outliers in the same range. In the previous chart, the T was the only agency in the range of the New York systems; in this metric, it is joined by three others: VTA (Santa Clara County/San Jose), Pittsburgh and Detroit. Still, it is 50% higher than its peers, so there is some room for improvement. Perhaps Pioneer’s conclusions should not be “we need to privatize everything and eliminate the unions” but rather “let’s see what these other cities are doing and what we can do better.”

Is Minneapolis the right analog?

Much of Pioneer’s study focuses on comparing the MBTA to MetroTransit, the bus system in Minneapolis, Saint Paul and the surrounding area. After comparing the T to the two lists of 20 cities (one of which includes MetroTransit) the authors focus in on comparing the T to one such agency which is more like the T. (And in a stunning use of logic, they don’t choose, say, El Paso.) MetroTransit operates a similarly-sized fleet to the MBTA, and also operates in winter weather (which is not the case for many “peer agencies” above). So comparing the T to Minneapolis is not a bad choice.

But are there differences that probably account for a lot of the difference? Certainly. First of all, Minneapolis carries about 215,000 bus passengers, about half as many as Boston. The average trip is longer, as buses are the workhorse of the system (the two rail lines combine for only about 60,000 passengers per day), so there are fewer bus-rail transfers. But the number of trips per revenue mile in Minneapolis is still only 60% of Boston*—in fact, Boston has one of the highest number of trips per mile of any system in the country.

[ * This will probably be lower in coming years, as Minneapolis replaced one of its busiest bus lines—the 16 and 50, connecting downtown Minneapolis and Saint Paul and accounting for 10% of the total system ridership—with a light rail line in 2014. This has led to a significant overall increase in transit use (already nearing 2030 estimates with 36,000 daily riders), but an overall decrease in bus patronage and the number of passengers per bus. The 16 ran at 24 hour service and 10 minute headways at most times of day and was supplemented by the limited stop 50, especially at rush hours. Combined, they carried 24,000 passengers per day. ]

Pioneer examines several years of data (to their credit) and I’m looking just at 2013 (because this isn’t, you know, my job), so there are obviously fleet age questions, but when looking at a sample of this size (2 cities), there are all sorts of questions. Did numbers spike some years because many buses went out for mid-life overhaul? Were old buses give only very necessary maintenance in anticipation of retirement? Did new buses coming online require much less maintenance? I’m not sure how much difference this might make.

But what I do think makes a difference are two factors:

- The Twin Cities have a much lower cost of living than Boston

- While Boston uses a variety of maintenance yards, some of which date back well in to the streetcar era, the Twin Cities made large investments in large, modern and enclosed maintenance facilities.

Boston is an expensive place to live. Housing prices are skyrocketing and affordable housing is somewhat hard to come by. Working on buses requires the ability to commute to a maintenance facility, most of which are located in areas with high housing prices, and staff need to be paid accordingly. Minneapolis is far less expensive. Housing prices in the Twin Cities in 2014 were just 53% as high as in Boston, and the overall cost of living was 16% lower. Since personnel costs are a large part of maintenance costs, it is not surprising that it costs more to pay staff in Boston.

Then there’s the question of capital investment. One of the reasons the T is reluctant to add bus service is that it can’t expand its fleet. The number of buses is constrained by yard space, and new bus yards don’t come cheap. Recent discussions about rebuilding the bus yard at Arborway have quoted figures in the range of $200 to $250 million, and that’s one of more than half a dozen facilities the T operates. Rebuilding enough bus yards for the whole system would likely be a billion dollar project, or higher.

What’s more, the current locations of the T’s bus yards are worth a lot of money, and would help with the regional housing crunch. One sits at Arborway, and could be sold for $20 million (or leased to a developer as well)—and the city would also reap property taxes from a property which is currently untaxed. Another, Cabot, sits steps from the Seaport District and South Station, Albany is similarly situated in the South End, and the largest is the Charlestown Yard, in a decrepit-but-transit-rich part of Sullivan Square. So there’s the opportunity cost of not selling these off for development as well. But having well-located bus yards is an asset to the T, as it’s non-revenue (“deadhead”) mileage is some of the lowest of any large system (11%), it can’t afford to lose any facilities without replacing that capacity, and large plots of land in warehousing or industrial areas are not plentiful in Boston.

What’s more, the current locations of the T’s bus yards are worth a lot of money, and would help with the regional housing crunch. One sits at Arborway, and could be sold for $20 million (or leased to a developer as well)—and the city would also reap property taxes from a property which is currently untaxed. Another, Cabot, sits steps from the Seaport District and South Station, Albany is similarly situated in the South End, and the largest is the Charlestown Yard, in a decrepit-but-transit-rich part of Sullivan Square. So there’s the opportunity cost of not selling these off for development as well. But having well-located bus yards is an asset to the T, as it’s non-revenue (“deadhead”) mileage is some of the lowest of any large system (11%), it can’t afford to lose any facilities without replacing that capacity, and large plots of land in warehousing or industrial areas are not plentiful in Boston.

Minneapolis, on the other hand, has relatively new bus maintenance facilities. Every facility has been built since 1980. (And there are only six facilities, as opposed to the MBTA’s nine, lending economies of scale.) With lower land prices and much less density, most of the facilities are relatively centrally located, yet don’t take up valuable, transit-rich land. What’s more, every bus facility in Minneapolis is fully enclosed. In Boston, most bus facilities consist of an open yard with a maintenance garage. In the case of Arborway—one of the largest facilities—it is a small, temporary building. Buses are by and large stored outside. In Minneapolis, nearly all buses are stored inside. There’s adequate room to work, and the buses being stored don’t sit overnight in freezing temperatures.

Even still, the Twin Cities’s bus yards are not as centrally-located as Boston’s (T yards are often shoehorned in to small parcels; MetroTransit yards are usually larger and squarer). While Boston runs 11% of its mileage out of revenue service (deadhead), the Twin Cities run 24% (and as far as hours go, Boston is 9% deadhead and the Twin Cities 14% owing to a larger and less-crowded highway system in the Twin Cities). To access these newer, more efficient facilities requires significantly more operation expense. It would be as if the T built new bus facilities in Billerica, Southborough and Brockton: they’d likely be more efficient, but savings would be eaten up driving buses back and forth to and from them. Given the T’s salaries, if their garages were located such that they required 14% deadhead hours like the Twin Cities, it would add $5 million to annual operating costs.

That being said, MetroTransit has certainly invested money in vehicle maintenance facilities that the T has not. If the T had spent a billion dollars on a set of brand new bus maintenance facilities, it would likely spend less on maintaining its buses. Of course, if we assume that there is $1 billion in deferred facility capital outlay and that a bus maintenance facility has a useful life of 50 years, it would cost $20 million per year to build those facilities, money the T is currently spending on other projects. I’m not saying that this is a logical way to do business; the T should budget for and build adequate maintenance facilities. But comparing a system with new, enclosed facilities with the T’s antiquated mishmash of bus yards and small garages certainly needs some qualification.

The T’s maintenance budget runs $40 to $60 million ahead of MetroTransit each year. But, again, there’s much more to this than meets the eye. If the T required as many deadhead hours as MetroTransit, it would cost $5 million extra in operating costs just to get the buses to and from the garage. Given the difference in cost of living, the T’s salaries are higher than MetroTransit’s. If we only look at salary, the cost of living difference accounts for $6 million of that difference, and if we add in benefits it’s $11 million. And then, there’s the $10 to $20 million annually that the T hasn’t spent on new maintenance facilities. Better fleet renewal and capital outlay for maintenance facilities would probably help the T’s maintenance budget: maintenance is not siloed financially from the rest of the transit system’s operation.

In 2013 the T spent $104 million on vehicle maintenance to MetroTransit’s $45, so I’ll use those numbers. I will note that was a year before the T accepted a large order of New Flyer hybrid buses, which should require less maintenance than the 20-year-old RTS fleet they replace. In 2013 T’s bus fleet (average age: 9.4 years) was significantly older than MetroTransit’s (average age: 5.1 years). (I’m not even accounting for the lower capital costs the T has with an older fleet, although the fleet age obviously manifests as higher maintenance costs.) This could certainly be reanalyzed for other years; by using the year when MetroTransit had a much newer fleet, this probably paints the T in a worse light than is actually the case. According to Pioneer, during years in which the fleets for the MBTA and MetroTransit were similar ages, the T’s costs were only about double MetroTransit’s.

In any case:

| Total Annual Expendeture |

$105m |

% of total |

| – Deadhead operation cost difference

– Cost of living difference (salary, salary+benefits)

– Facility construction |

–$5m

–$6m-$11m

–$10m-$20m |

5%

6-10%

10-19% |

| Adjusted total |

$69-$84m |

66-80% |

| % of difference |

$21m-$36m |

35-58% |

| † Adjusted total ($90m MBTA) |

$55m-$70m |

22-39% |

| † % of difference ($90m MBTA) |

$20m-$35m |

44-78% |

† From 2006 to 2009, MBTA costs were about 200% of MetroTransit costs, and the bus fleets’ ages were similar. Assuming that if the T had a similarly-aged bus fleet to MetroTransit and double the costs, it would have a $90 million maintenance budget. If this is a good way to account for the fleet’s age difference, between 40 and 80% of the difference could be explained by deadhead operation expenses, cost of living and facilities.

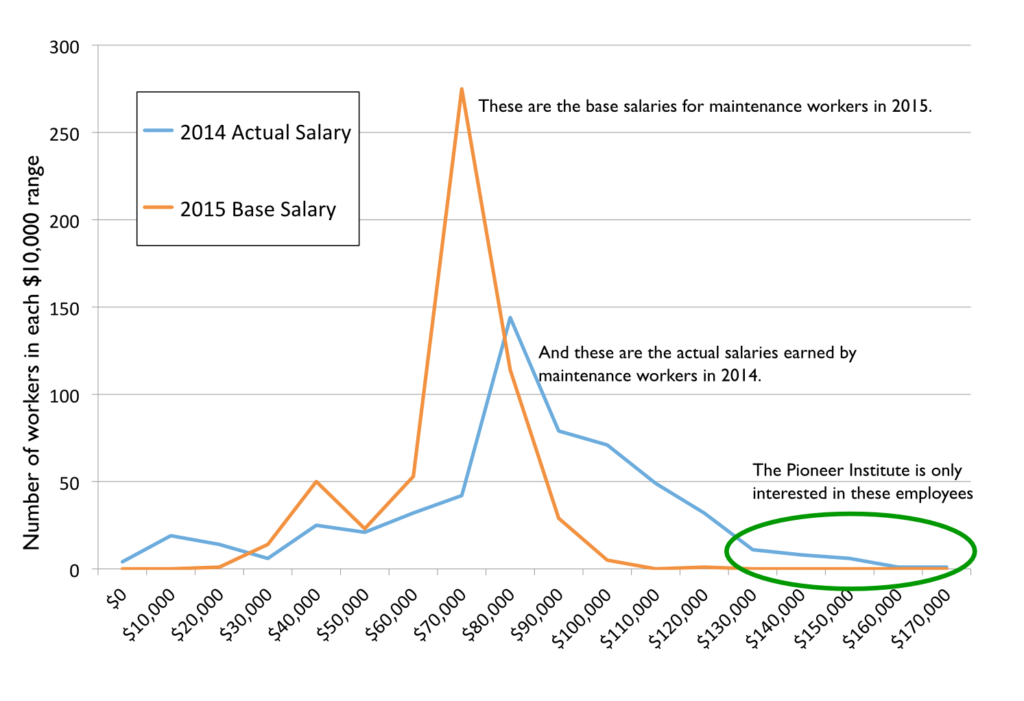

Citing high salaries as a scare tactic

One of the favorite pastimes of the anti-union, anti-government folks is to find someone who works for the government and makes a lot of money and hold it up as an example of government waste (well, unless it’s a football coach; they’re fine with that). In their report, they go and find examples of people making a lot of money (a painter making $80,000! A machinist making $120,000! A car cleaner bringing home $70,000!) and use this to show how wasteful government is. But, of course, this is hyperbole. These are outliers: probably people who worked a lot of overtime—some 60 hour weeks—in order to make that much money. Since transit runs 24/7, there’s overtime to be had: a few extra buses break down, or someone calls sick and a worker picks up an extra shift. Are there some savings to be had from better oversight of overtime? Probably. But without showing the average numbers, these are pure scare tactics, a rhetorical device that doesn’t stand up to any scrutiny. Luckily, I have the T’s salary database sitting around (which is public record, of course), so we can do some such analysis.

|

Yes, all MBTA salaries are public information.

You can access the file here. |

It’s unlikely the T will ever be able to use non-union employees, even if maintenance is privatized. Given the construction boom in Boston, these salaries do not seem far out of hand for union labor (union sheet metal workers, for example, make nearly $100 per hour, or $200,000 per year, although they don’t of course, have the job security a T worker does). Here are the base salary ranges for the major employment categories among the T’s bus maintenance personnel:

| Fueler |

$34964 – $43014 |

| Machinist |

$57262 – $77750 |

| Car cleaner |

$60278 |

| Painter/Carpenter |

$82035 |

| Foreman |

$87672 – $100672 |

| Sheet metal |

$89669 |

| Pipefitter |

$94994 |

| Wireperson |

$95617 |

On average, employees earned 119% of their 2015 base salaries in 2014. Why? As mentioned before, overtime. Could the T hire more employees and pay less overtime? Probably. But if they did, there’d be outcry from Pioneer about how even more workers were getting the platinum-level union compensation package and benefits. They want to privatize operations, and assure lower pay and benefits for everyone. Is that a way to treat public employees? I’m all for accountability, but it shouldn’t require these sort of threats.

To add it all together …

Pioneer’s top line statement—that the T could have saved $250 million in bus maintenance costs over 6 years—is specious. They massage and manipulate data, but it doesn’t stand up to any scrutiny. Does the T have some of the highest maintenance costs around? Yes, it does (although New York is higher still). Some of this is due to the operating environment, some is due to local costs of living, some is due to the lack of appropriate facilities and, yes, some may be due to the performance of MBTA employees. The T could probably reduce it’s overall maintenance expenditures with different management practices, but to insist that those are put in to place without any funding (for instance: to insist on better management while many repairs take place in outdated and/or temporary facilities) is just silly. To use blatantly and obviously manipulated numbers to make this argument is disingenuous, and, once examined, the Pioneer Institute’s argument falls apart. There is very little defense for this sort of sloppy “analysis,” and it certainly should not be relied upon to make policy changes.

Using several different—and more honest—metrics, we can explain away much of that difference:

- 60% of the Pioneer Institute report’s difference in costs arise from their suspicious definition of “peer agency.” Of the $250 million that they claim the T could save, that accounts for $150 million of it.

- Just by using maintenance cost per hour instead of maintenance cost per mile, the difference is 20% lower.

- In comparison to the Twin Cities, we can explain 35% to 75% of the difference in costs between the two systems.

The Pioneer Institute had an agenda: to reduce the power of public employee unions and privatize all that they can. Their position may well be “why spend time and money figuring out how to reform our management when we can just outsource it and let the magic of free market competition figure all that out for us, via a contractor, now?” But without good data on other systems (Has any large system privatized and had major cost benefits? They don’t say.) this is a hollow sentiment. And the MBTA’s current contractors have been doing a

less-than-stellar job of late: the publicly run subway operations recovered from the blizzards far more quickly than the private-contract Commuter Rail system.

Pioneer saw a well-compensated set of individuals, and tried to make a case that they are lazy, that they have a poor work ethic, and that compared to their peers in other cities, that they have poor work quality. It’s true that MBTA costs are higher than many other agencies, and the T could probably implement policies to bring costs down to some degree. Upon further examination, however, it is the “research” coming from the Pioneer Institute that is low quality, not the work of the maintenance department at the MBTA.