Early Monday morning, on Twitter, Cambridge City Councilor Jan Devereux posted this photo of the taxicab line at Logan Airport:

The line for taxis at Logan (not TNCs) has 100+ people after midnight. The TNC pickup equally chaotic & crowded. Insane. pic.twitter.com/IjYPI1X1OR— Jan Devereux (@jandev) October 28, 2019

Then she went to check out the Uber/Lyft line and it was no better:

Meanwhile it’s a zoo in the TNC line at Logan @Massport @MassGovernor 12:46am Sun night pic.twitter.com/W2z4IOW29f— Jan Devereux (@jandev) October 28, 2019

By 1:30, others reported that the cab line was an hour long.

Things got even worse after 1:30am. Made it 3/4ths of the way down the cab line in 45 minutes before sharing a ride.Late night SL service noted for next time! pic.twitter.com/Od4MuY3dvG

— Ryan Cullen (@transporyan) October 28, 2019

What’s going on here? Where are all the taxis? Where are all the Ubers? Why are people arriving at the airport after midnight then waiting an hour for a ride home? What can we do about this?

It’s not really a simple answer. Please, though, follow me down a rabbit hole.

Logan airport is not a hub airport (okay, not really: Delta and especially JetBlue are doing their best to create a hub, but it still is mostly an origin-destination airport). This is a matter of geography: because it is tucked away at the northeast corner of the country, the airport mostly handles passengers flying in one direction, south or west, either on direct flights, or to other domestic hubs (although international travel has increased markedly in recent years, and JetBlue even has a bank of later domestic flights to accommodate connecting passengers).

Boston’s flights can be grouped in to three main types: short haul flights to non-hub cities, short-haul flights to hub cities, and long hauls, both domestic and international. Only the first group operates without geographic constraints which dictate that flights can only arrive and depart at certain times of day. Non-hub short-haul flights, mostly on JetBlue and Delta (to places like AUS, BUF, RDU, MKE) are spread more evenly throughout the day, because they don’t have to make connections at hubs. Hub-based flights within the eastern half of the United States (say, as far as MIA, DFW and MSP). These flights account for many of the early departures, but few leave Boston after early evening. They don’t arrive in Boston until mid-morning, but are the bulk of the last flights arriving later in the evening. Because of these travel patterns, Logan has a lot of early and late flights: in the morning, people want to get to a connecting hub for the first “bank” of connecting flights, and in the evening, flights have to leave the connecting hub after the last bank has occurred.

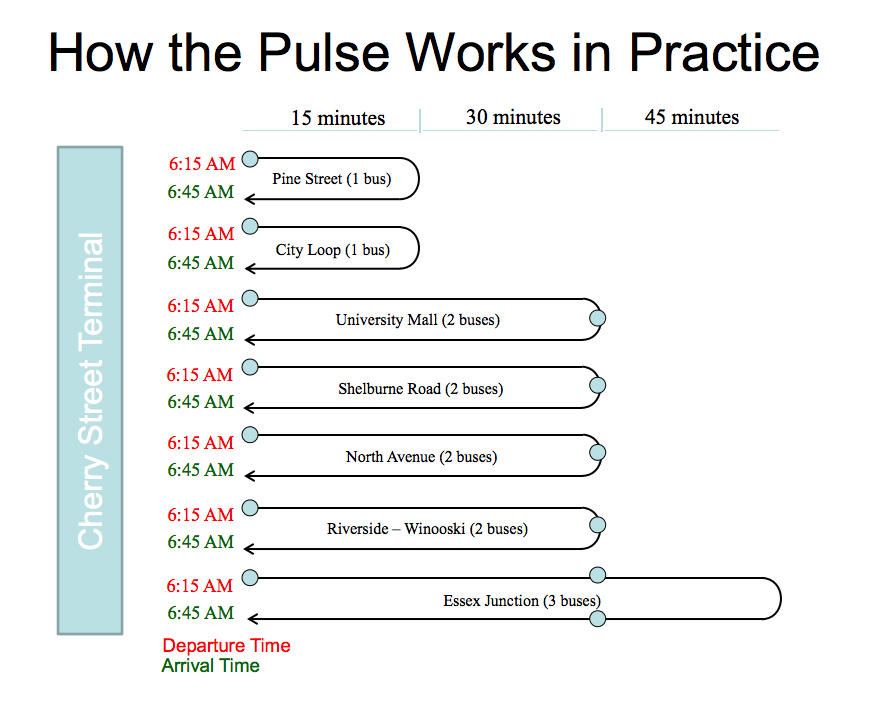

(Not all airlines utilize banking at hubs—Southwest most notably runs continuous hubs—and there are pluses and minuses to each method, about which I won’t go into too much depth here. But basically, banking decreases fleet utilization and increases congestion at hub airports since flights arrive and depart all at the same time, followed, in some cases, by periods of relatively low flight activity, but passengers have much shorter connection times at hubs since connections are coordinated. It’s actually something like a pulse system for buses, except that airports have finite numbers of vehicles which can arrive and depart at any given time, and longer dwell times. As airlines have consolidated, hubs have grown and seen more frequent banks such that they are now closer to continuous operation, especially at large airports like Atlanta and Chicago. See how this is a rabbit hole? Also, when I say people want to connect to the first bank, I mostly mean airlines, no rational human being wants to be on a flight departing at 5:15 a.m.)

Then there are longer-haul flights. Transcons have to deal with time changes, cycle times, and the fact that flights generally don’t depart or arrive between 1 a.m. and 5 a.m. local time. So they arrive from the West Coast either as redeyes between 5 and 10 a.m., and then turn to depart between 6 and noon, or as day flights, arriving in the afternoon or evening. Thus, in addition to the overnight lull, there are basically no transcons which arrive in or depart Boston during the midday. International flights (mostly TATLs) generally are redeye flights going out, leaving Boston in the evening, and return during the middle of the day, arriving in the afternoon. All told, Boston has demand throughout the day, but particularly high demand for flights arriving later in the evening.

For instance, O’Hare and Atlanta, the two busiest airports in the country (by number of aircraft movements), have 29 and 24 flights scheduled to arrive after 11 p.m., respectively. Boston has 39. After 11 p.m., Boston is basically the busiest passenger airport in the country (about tied with LAX), and possibly the world (since in many countries, airports have noise regulations which limit late night flights). Yet at the same time, there are few flights departing Boston. The airport has only 14 scheduled departures after 11 p.m., and only six of these are domestic flights (all are JetBlue E190s, so they’re small planes). There is basically zero demand for passengers to get to the airport late at night. This creates a demand imbalance for ground transportation: there’s a lot of demand to leave the airport at midnight, but almost no one who wants to go there.

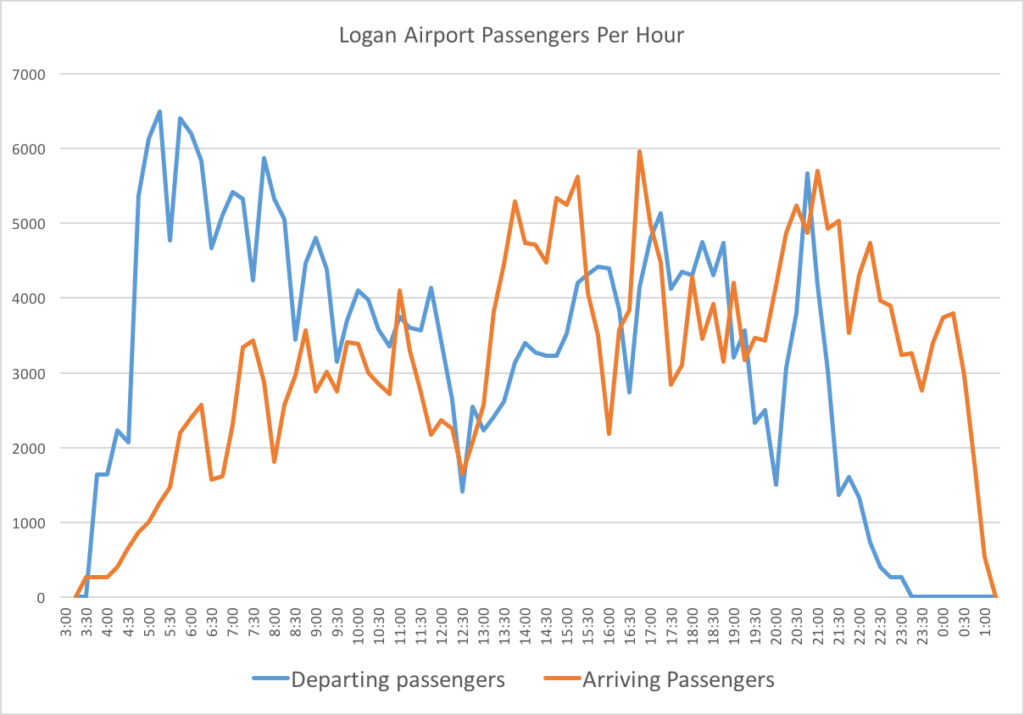

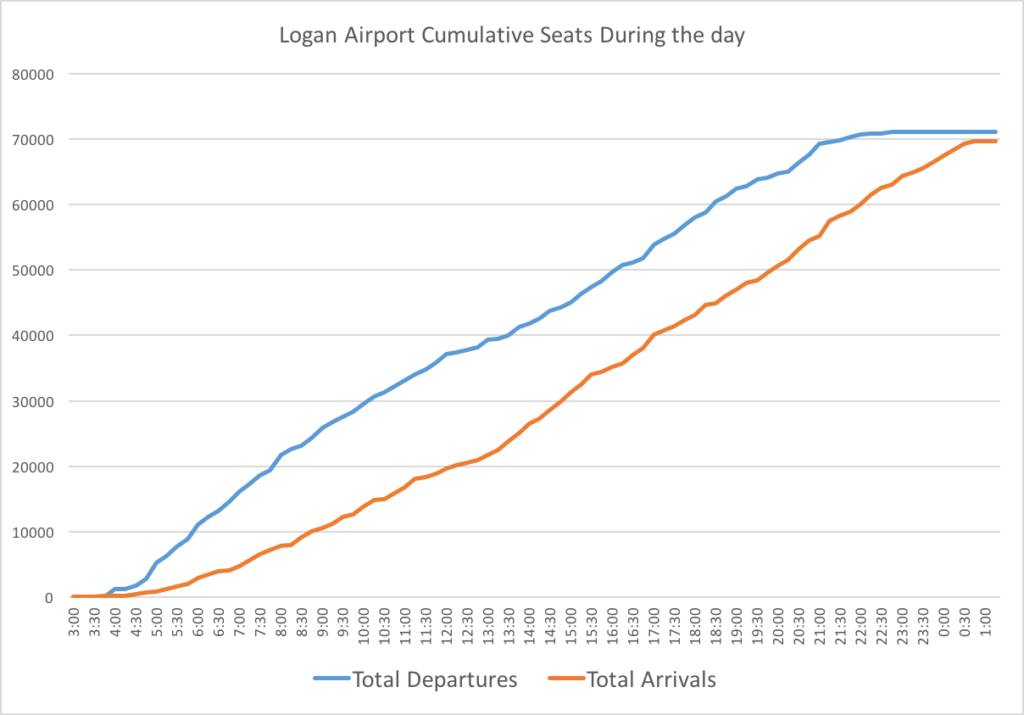

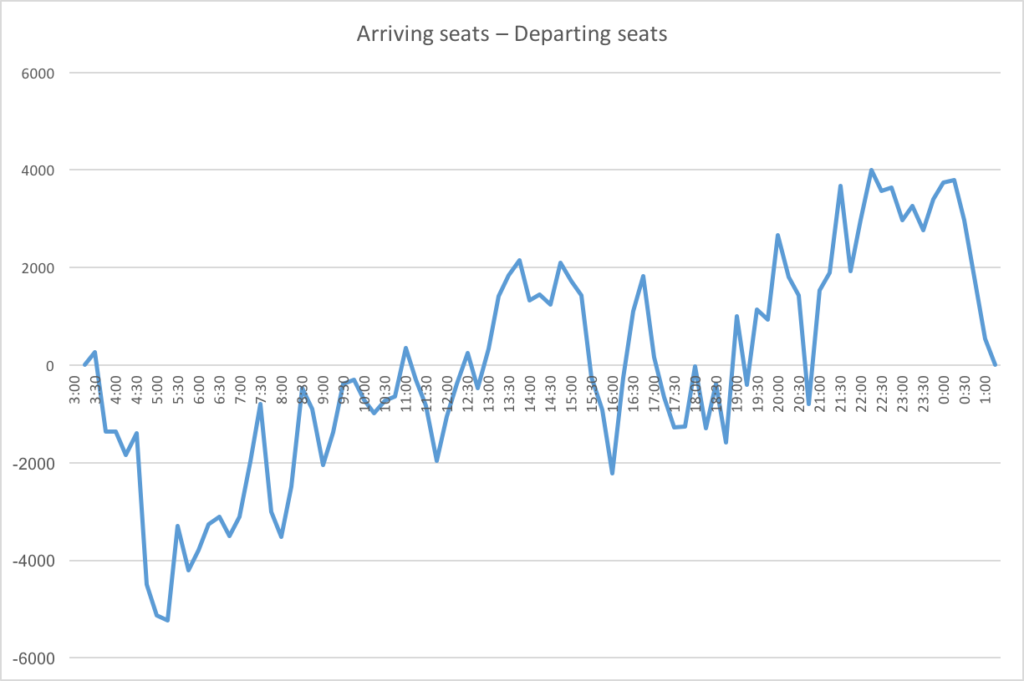

Here are some charts of the approximate number of airline seats arriving and leaving Boston. I adjusted for the typical arrival time at the airport (60 minutes for domestic, 120 for international) and assumed it would take 30 minutes for the average international passenger to clear customs.

(Note, the seat numbers for arrivals and departures don’t exactly match because each day at Logan is not identical and this was a snapshot of a day. This is total seats available, not total passengers, and is also a rough estimate based on plane sizes at different times of day, but should show general trends well.)

So, it’s clear that there is a good deal more demand to get to the airport in the morning, which doesn’t even out until around 9 a.m., various points of imbalance during the day, and then, starting around 7 p.m., significantly more demand to leave the airport.

A couple of personal anecdotes can illustrate this. The first illustrates the imabalce in the morning. Back before the Big Dig was completed (and, in fact, pre-Silver Line, and back when the airport had half the traffic it has today), when I was going to college, getting to the airport was, perhaps, worse than today. It involved both the elevated Central Artery and then the Sumner/Callahan tunnel complex: a trip to or from the airport to downtown could take an hour (which is, of course, not much different than it is now). For several years, however, the Ted Williams Tunnel had been open to commercial vehicles only. The connecting highways were not yet complete, so this was a way to keep the local streets from getting overrun by people trying avoid the congestion.

From Newton, where I grew up, my father came up with a solution, especially for early morning departures. He would drive me to South Station. Rather than risk the airport traffic, I’d get in a cab for the usually $10 or $12 trip under the harbor in the tunnel only cabs could use. Early one morning, I got in a cab at South Station and told the driver I was going to the airport. He quoted the fare: “$20” and didn’t turn on the meter. What I should have done is say “I’ll pay you whatever the meter quotes at the end of the ride, so it’s in your best interest to turn it on now,” but I was 18 and hadn’t quite figured that out, so at the airport, I paid him $20, noted his medallion number, and immediately reported it.

A month later my dad got a check for $20 from the Boston Police (which oversee taxi medallions), along with a note that the taxi driver had been given a stern talking to that he was never to refuse to turn on the meter for a trip within the city.

But I understand why the driver was reticent to take the fare. He would get to the airport and have two (bad) decisions. One would be to go to the taxi pool and wait in line for an fare back to the city: a long line, because there is much less demand going in to the city at 7 a.m. than there are taxis arriving at the airport. The other would be go cross back downtown without a passenger, but still incur the cost of driving, as well as the tunnel toll (which was one-way inbound at that point), with no passenger to pay it. Still, because of redeye arrivals from the West Coast in the morning, there is some traffic for cabs that do make it to the airport going back, although they have to cycle through the cab pool (or the Uber/Lyft pool) before their next fare. Even now, if you take a cab or a ride-hail vehicle to the airport in the morning, the driver is probably not particularly happy taking the fare.

The second example was an extreme example of the late-night issue. I was flying back from SLC and the flight was delayed several hours. Originally scheduled in at 11:30 (plenty of time to catch the Silver Line downtown and take the T home), the plane was more than three hours late, and didn’t arrive in Boston until about 2:30. The airport was empty. Yet a 757 had arrived with 200 passengers, and no one was making the trip at that point to pick us up. So we all converged on the cab stand, but there wasn’t a cab in sight. Immediately, people started self-pooling: it was clear that if we all took our own cabs, the line wouldn’t clear for hours. “Who’s going to Brookline?” “I’m going to JP, that’s close!” “I’m going to Concord.” “I’m going to Lexington, let’s share.” Every few minutes, a stray cab would roll up, three overtired strangers would pile in, and the line would get slightly shorter. I found a cab pretty quickly, but imagine those at the back of the line may have seen the sun rise.

Finally, here’s a picture of the departures level at Terminal A at 8 p.m. this past week.

Delta’s last domestic flight leaves at 7:45 (to MCO) and the last hub-based flight leaves at 6:56 (for ATL). Two international flights leave around 8:30. At this time, it’s a ghost town. Note: if you’re picking someone up at the airport in the evening, plan to meet them on the upper level, and note that Terminal A is a great place to wait without having State Police harass you. (Terminal B was pretty quiet, too.)

Here are scheduled arrivals and departures, by carrier, at different times of day:

Note: not all regional flights appear to be in this sample, for instance, there are no Cape Air flights shown after mid-evening, when Cape Air flies several late flights out of Boston, but these flights are minimal as far as number of arriving passengers is concerned.

Notice how departures peak in the morning, then lull in the midday, and then have a secondary peak in the evening, before domestic departures (except for JetBlue) tail off quickly after 7 p.m. International carrier flights are clustered arriving in the afternoon and leaving in the evening. But there is a clear imbalance for flights arriving and departing the airport.

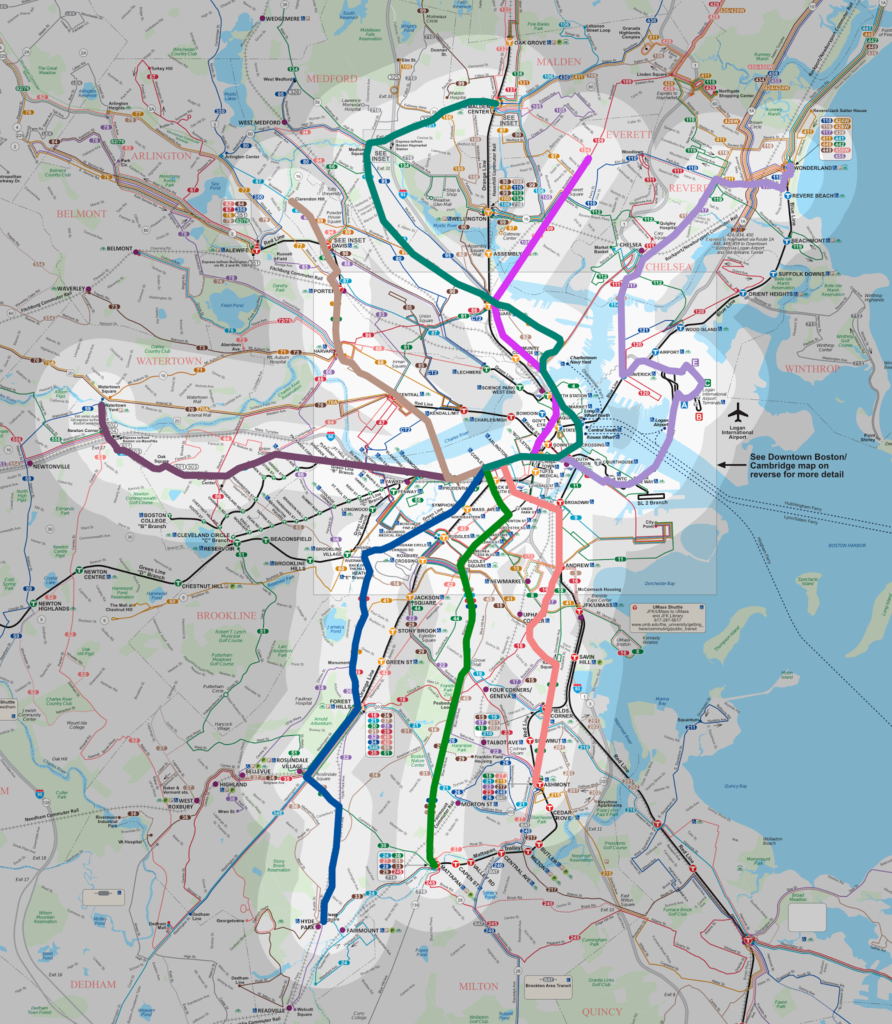

In any case, this has been a problem for years, and it’s a structural issue pertinent to Logan Airport based on the airport’s geography on both a macro and micro scale. On a macro scale, the geography of the airport at the corner of the country means that, late in the evening, flights feed into it but don’t feed out. On a micro scale, the airport’s geography encourages taxi/app-ride/ride-hail use (I’ll call these taxis, for simplicity). The constrained location means that parking costs are high, because demand for parking outstrips supply. The proximity to areas with high trip generation (downtown, and high density areas nearby) means that taxi costs are often significantly lower than a day’s parking cost ($38) in the garage. The combination of these factors push many people to use taxis.

Much of the day, taxi supply roughly matches demand, and there is a minimal delay for these services. But this breaks down at the beginning and end of the day, especially in the evening. Once again, Logan’s geography comes into play. While the airport is close to the city geographically, it is expensive to get to for a taxi driver. When there is high demand for fares back to the city at 1 a.m.—especially once buses have, for the most part, stopped running—there is negligible demand to get to the airport, or even East Boston in general, so to pick up any fare would require the driver to deadhead to the airport.

Unless a driver happens to pick up a stray fare to East Boston, this requires a driver to travel several miles, and to pay the cost of the tunnel toll. Once at the airport, there is no promise that the trip home will be lucrative enough to cover these costs. They might get a $50 fare to a far-flung suburb. But it might only be a $15 fare to a downtown hotel or, worse, to Revere or Winthrop, meaning a driver would then have to drive back home—likely through the tunnel—and foot the bill for the toll both ways. Moreover, this is the end of the day for most drivers: except on a Friday or Saturday night, there is only so much demand for rides after 1 a.m. For many drivers, the potential upside of getting a decent fare from the airport doesn’t make up for the potential downsides, especially when the alternative is shutting off the app (or taximeter), driving home, and going to bed an hour earlier. There is a high disincentive to be in the last group of taxis at the airport: a driver might get one of the last passengers, but if not, there is not likely a job for several hours when the first redeye flights start to trickle in around 4 a.m. There is little incentive for taxicab drivers to go to the airport during this dwindling time, so demand is only met by drivers already in East Boston who need a fare back to the city.

This is not an easy issue to solve. It also shows why Uber and Lyft are basically just taxis: they are subject to the same supply and demand issues that affect the rest of the market. Alas, they’re providing the same service: a chauffeured ride from Point A to Point B. And the airport is pretty much the only place that cabs still have a foothold, partially because matching passengers to specific vehicles is quite inefficient with large groups, like you might find at an airport. This has been a recent point of contention at LAX, which consolidated its taxi and ride-hail facilities away from the terminals (as Logan is planning). It hasn’t gone particularly well to start, but I would venture to guess that there are similar supply and demand issues at LAX. (As several people have pointed out, the buses there are running much more smoothly, too.)

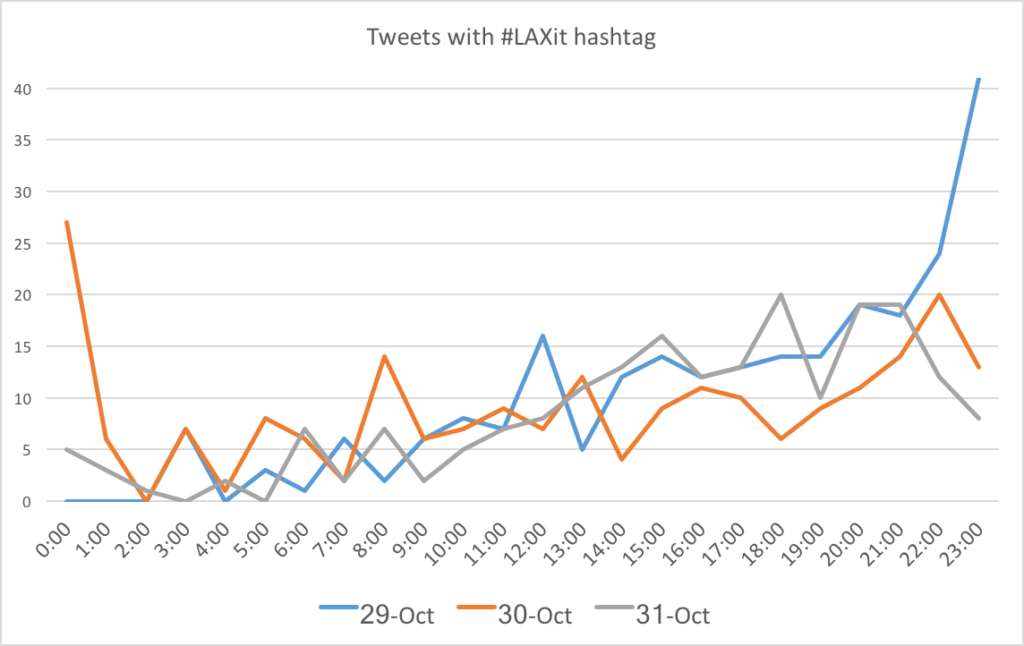

Of course, at LA, there is a temporal aspect to the complaints about #LAXit. Most of the issues are in the evening. Los Angeles has more balanced operations, with plenty of departures in the evening, both redeyes to the East Coast and transcontinentals, mostly TPACs but some TATLs as well. There is probably both more demand for cabs in the evening because LA is on the opposite side of the country as Boston, and also because most of the transcon redeyes leave before 11 p.m., and most of the later flights are international, which are fed more by connecting travelers and by passengers arriving at the airport much earlier. Thus, for the actual demand for taxis, there is a similar, if less pronounced, demand compared with Boston.

I scraped Twitter for #LAXit from the first few days and it seems clear that the issue is mostly in the evening.

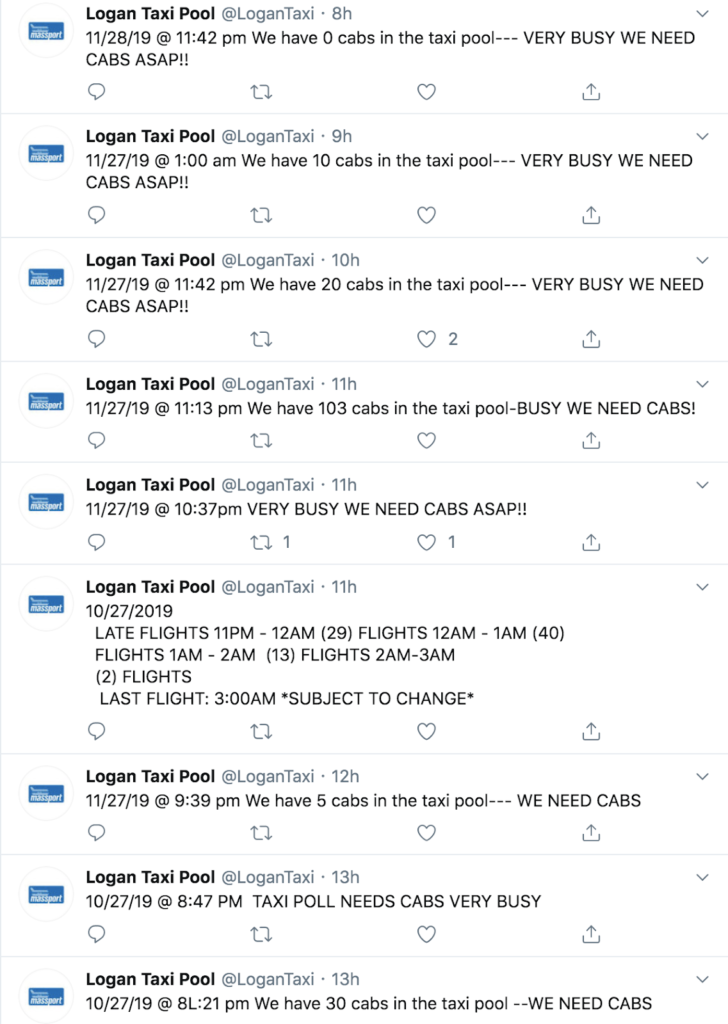

But back to Boston. Here’s what the Logan cab pool Twitter feed (because of course Logan’s taxis have a Twitter feed) looked like last Sunday. There was a cab shortage by 8 p.m., and the late night arrival issue was foreseen by 10 p.m. It wasn’t a surprise. It is a market issue.

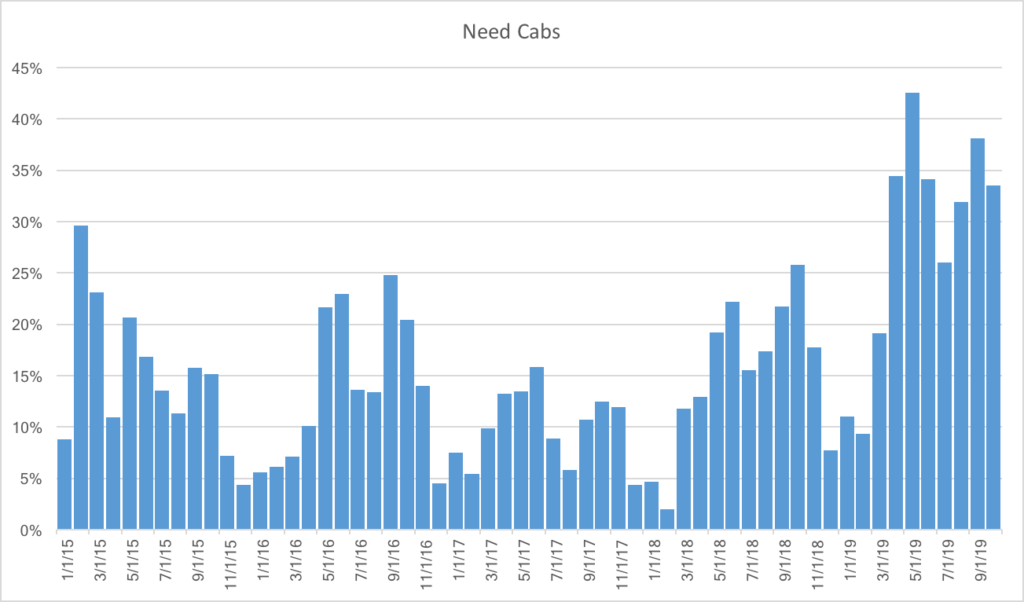

Is this feed a bot? Certainly not! Note the wrong months, typos, misspellings, random numbers of hyphens and use of quotations. The one thing that seems constant is the use of the word “need” when the airport has a cab shortage (with various qualifiers like all-caps or exclamation marks). I’m pretty sure it’s a guy standing by the taxi pool furiously typing tweets into the Twitter machine. So, I decided to scrape the feed (about 60,000 tweets), and code each tweet by whether it included the word “need” or not, to get a very rough estimate of the frequency of taxi delays at Logan.

From the charts of arrivals and departures above, we would assume that the airport would generally need cabs mid-afternoon, as well as in the evening. If we chart the arrival and departure relationship and the Twitter feed’s need for cabs together, and we shift the need for cabs back 1:15 (probably due to actual behavior of arriving passengers), voila, they match pretty darned well.

A few other notes on the need for cabs:

- There is more demand on Sundays (36% of Tweets include the word “need”), followed by Mondays, Thursdays and Fridays (28%), with the least demand on Saturdays (20%)

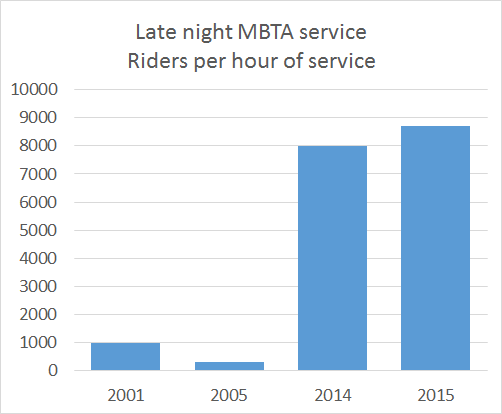

- The cab shortage is generally higher in the summer than the winter (and highest in May, June, September and October, while lowest in December, January and February), and it has been particularly high this year. In fact, the only higher demand for cabs at the airport was in February of 2015. I wonder why.

TL;DR: it is definitely getting harder to get a cab at the airport, especially during certain times of the year and at certain times of day. And when flights are delayed, this is exacerbated. Departing passengers generally still get to the airport on time, but arriving passengers get in later, meaning the cab shortage is even more acute. Which leads to situations like the one which occurred earlier this week at the start of this post, which may have taken you nearly that long to read

So what can be done about it? Well, Uber/Lyft could use their surge features to increase the cost of a trip to the point where it would make economic sense for drivers to come to the airport at this time of day. But that might double or triple the cost of a ride, so while it is a very market-based solution to the problem, it is not consumer-friendly. It (and taxi starters) could do a better job of pooling rides, and moving the Ubers and Lyfts to the same site might make pooling easier there. A very low-tech idea might be to figure out where vehicles are going and, at high-demand times, put people into lines based on regions to help them self-pool. This might nibble around the edges on the demand side, but it doesn’t help supply. It turns out that Lyft and Uber are not a magic panacea to mobility: they are subject to the same supply and demand issues as the rest of the world. And if the answer is pricing, it’s not a great answer, especially since prices might have to go up significantly to provide enough supply or suppress demand enough to satisfy market equilibrium, especially after midnight when there are really no other options available.

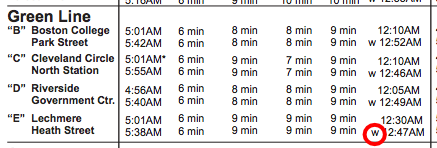

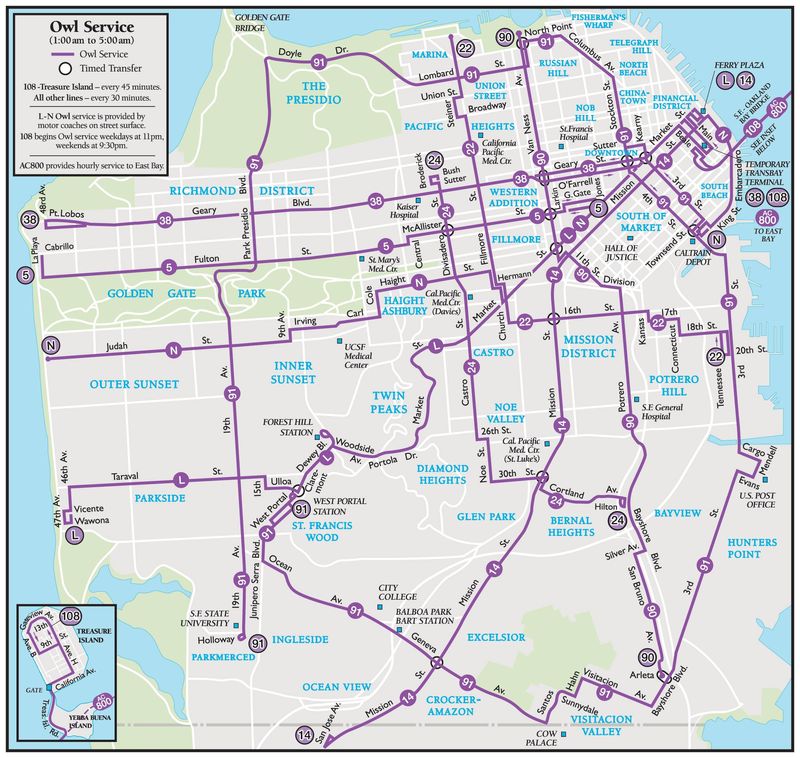

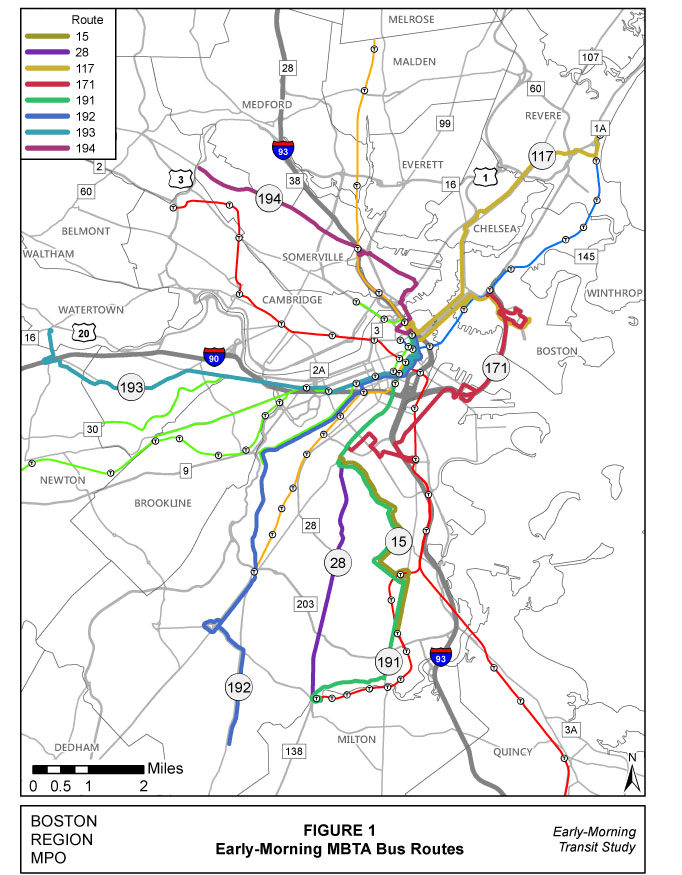

One solution, I think, is that rather than trying to bring supply to the demand, we should move the demand to where there is more supply: get people, en masse, downtown. This requires a magical invention: the bus. While the supply of hire cars is not limitless (there are only about 1800 taxicabs in Boston, and probably far fewer are active today, and many more Ubers and Lyfts, but a finite number), it is significantly less constrained on the other side of the Harbor. Instead of trying to entice drivers to come to the airport, we could instead move riders to where are there are more cars. Most riders are going north, west or south of the airport, and need a ride through Downtown Boston anyway. The bus might not be that appealing to a traveler at 1 a.m., but neither is a 45 minute wait for a cab. This basically takes what LA is doing, and extends it a couple of miles.

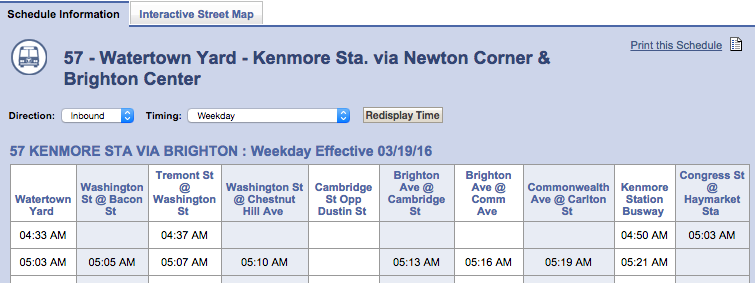

The MBTA runs the Silver Line until 1:15 a.m., which could easily bring passengers to South Station, where catching a taxi or ride hail vehicle is easier than at the airport. Massport and the T, however, do a poor job of advertising these late buses, both with signage telling passengers the hours as well as real-time information about the buses’ whereabouts (important especially if you are unsure if the last bus has left). But these are easy issues to solve. The bus real-time data is available: I have no issue pulling it up on mbtainfo.com, for instance.

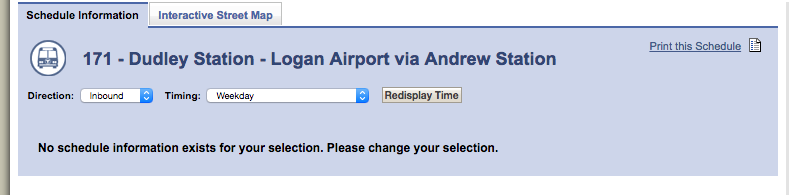

Not helpful, especially if you’re trying to figure out if the last bus has left, or even deciding if it’s worth waiting in a cab line versus waiting for the bus.

And Massport could put up static signage:

And as I’ve written before, with some minor schedule tweaks, the T could use the Silver Line 3 returns from Chelsea to supplement this service even later, and keep one bus in service to make an extra round trip to provide service until 2:30 when, on most nights, the planes have all landed. Alternatively, or in addition, Massport could continue its Back Bay Logan Express bus later in the evening and into the early morning (or even 24/7), providing late night trips to the taxicab-rich parts of Boston when there are cab shortages at the airport (and perhaps even direct service to large hotels in the Back Bay).

Even more, the Logan Taxi Twitter feed often includes this kind of Tweet:

10/31/2019

LAST FLIGHTS 11PM – 12AM (22) 12AM – 1AM (17) 1AM-2AM (7)

LAST FLIGHT 3:29 am. *SUBJECT TO CHANGE*— Logan Taxi Pool (@LoganTaxi) November 1, 2019

By 10:00 most evenings, someone at Logan knows how many late flights are coming in. So, conceivably, the bus driver could be held on duty to make extra trips in the cases of delays. Massport, which already helps to subsidize the fares for the Silver Line, could shoulder the rather minimal cost of the extra trips. And passengers arriving at midnight would no longer have to face an hour-long wait for a cab, when there are many more options across the harbor.

The market has never provided enough cabs at Logan when they are needed, and at certain times of day, lines of cabs are the rule, not the exception. Assuming the market will take care of this has never worked, and it is unlikely that it ever will. If Massport worked with the MBTA, however, it could pilot a project to move people downtown and create a secondary taxi queue there, where drivers would be much more willing to go for a fare, because even if the demand had dried up, they wouldn’t be out the tunnel tolls, mileage and time to show up at the airport.