(And, 2024 update, bonus on long, tall arch bridges!)

I haven’t posted here in a while (year and a half!) but with the demise of functional Twitter and figuring out HTTPS on my site (which … took me longer to do than it should have, sorry to everyone who attempted to enter their credit card to give me all the money and wound up giving it to a Nigerian Prince, but, really, I have a Patreon, it’s for my ski-related podcast but you can certainly click buttons over there) I figured it was time. In any case, I have a new job, I can probably not post about a lot of things, but now instead of long, ramblingTwitter threads, I’ll probably just post long, rambling posts here. Anyway …

Alon wrote a blog post nearly a decade ago about using highway medians for rail, and the differences between the US and Europe. It’s informative and mostly on-point, but I think he missed a couple of nuances and I’m going to go down a rabbit hole about a couple of them, specifically a) that roads are often less curvy than design limitations (with a nifty Google Maps way to measure that) and b) in most cases, European motorways/autobahns do not have wide medians, while North American roadways often do.

Highway medians: Europe vs America

First, a story: this summer, I was in Berlin (having gotten there from FRA via 9€ train), and was supposed to take a train to Frankfurt, meet my girlfriend (2024 edit: my wife!), and take another train (or maybe the same train) to Switzerland for some mountain time. Instead, I got the covid, got holed up for a few days, and walked around Berlin and looked at tram tracks. In a fit of genius, she suggested we rent a car and drive the die Autobahn mit the windows down (she’d been exposed along with me and had had it a few months before, so this seemed like a reasonable precaution) and so we rented a car at BER (which exists!) for the trip south to almost-Basel (much more expensive to return the car in CH than DE).

Was it how I had planned to cross Deutschland? Nein! But it was an interesting trip. My experience driving stick is limited to 20 years ago in New Zealand and a few days practice on her Fit. But once I got into gear in a rest stop, I could handle the autobahn fine (I even made it through a traffic jam, sorry, someone else’s clutch). I topped out at 183 km/h, slower than the ICE but plenty fast with the windows down. Sidebar to the sidebar: driving the autobahn is very civilized. There are rules: no passing on the right, overtake and then change lanes, no trucks on Sunday (this was a Sunday) and 100 mph didn’t feel that fast. 120 did, the Opel handled it fine, and I kind of wish I’d looked up the premium for renting a BMW. After 900 km we stumbled into a Michelin star restaurant (quite accidentally: it had the cheapest single rooms in Lörrach) and had a lovely meal that I could mostly taste.

Anyway, one thing I (sort of) noticed at 100 mph was that the autobahns do not have wide medians. There are some exceptions; like crossing the Swabian Jura between Stuttgart and Ulm, where the A8 splits into two roadways a mile apart, once of which runs on an old bridge under the Filstal high speed rail viaduct. with some gnarly curves, apparently this is a dangerous part of the network. But in general, medians for rural highways in Germany are only a couple of meters wide. France, too, where they sometimes get by with just a metal guardrail. Italy, Poland, Britain, Spain all seem the same.

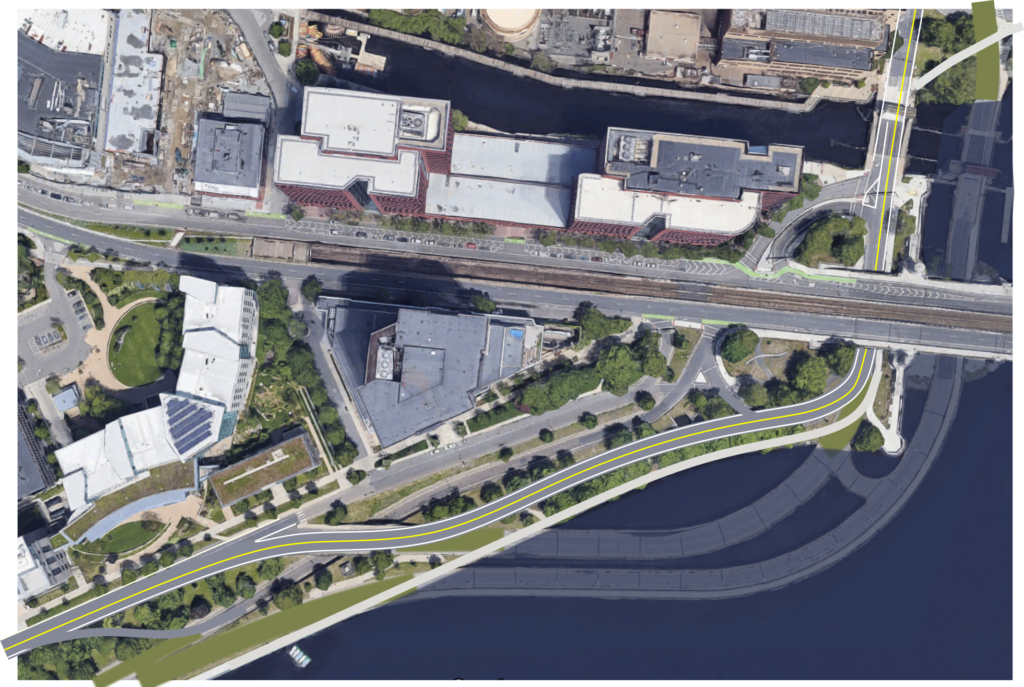

Last year, the Wendlingen-Ulm high speed line opened along Autobahn 8, and outside of the aforementioned area (where it’s mostly tunneled) much of it follows along the side of the A8, because there’s no median. A side-running routing means that exit ramps become complex to build (such as here, in Merklingen), requiring much longer bridges and complex entry and exit ramps or, in this case, a tunnel. Putting the railroad in the median would obviate the need for any of these issues, especially retrofitting rail into an existing roadway layout, but those medians don’t exist in Europe.

They often do in the US. Newer roadways in open, rural areas often have medians which are 50 feet wide or wider. In many cases, these are grassy medians which do not require any guard rails, the assumption that if a car goes into the grass it will decelerate enough before it crosses to the other side. The medians can also be used for drainage when they slope down between the roadway.

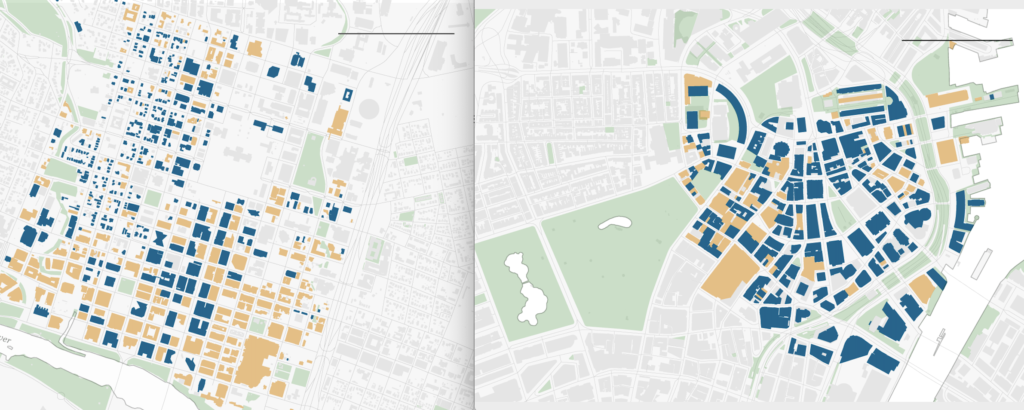

As such, there are a number of Locations in the US where railroads already exist in highway medians. Several of these are transit lines in urban areas, where—to vehemently agree with Alon—they don’t belong (in many cases, the roadways were designed to accommodate rail lines, or even replace them). The width of these medians (between inside solid yellow lane lines) varies, and none has high speed rail:

| Location | Width (ft) | Type | Notes |

| I-25 New Mexico | 100 | CR | Retrofit, single track but designed for 2. |

| DC Metro | 65 | HR | Often in roadways designed for rail, several examples. |

| Chicago | 46-75 | HR | Wider Congress originally designed for 4 tracks |

| SF BART | 55 | HR | Dublin, other examples exist. |

| Albany, NY | 46 | Freight | Urban area |

| Portland | 58-82 | LR | Wide inside shoulders |

| LA C Line / Century Fwy | 35-55 | LR | Built 1980s-1990s, light rail included as mitigation. |

Many, if not most, rural interstates have wide medians. To route a rail line alongside in very rural areas, it doesn’t matter much if a median is used or not: exits are widely spaced there’s plenty of room to rebuild them, and sticking to a median may require shifting over or under the roadway for curves, so it depends on the roadway curvature. Cities rarely have wide medians and they’re decidedly bad places for transit anyway. There are, however, “happy medium” areas where median-aligned rail might make sense, especially in more built-up areas where highways have wide medians and railroads could benefit from higher—if not truly high—speeds.

Measuring curvature with Google Maps

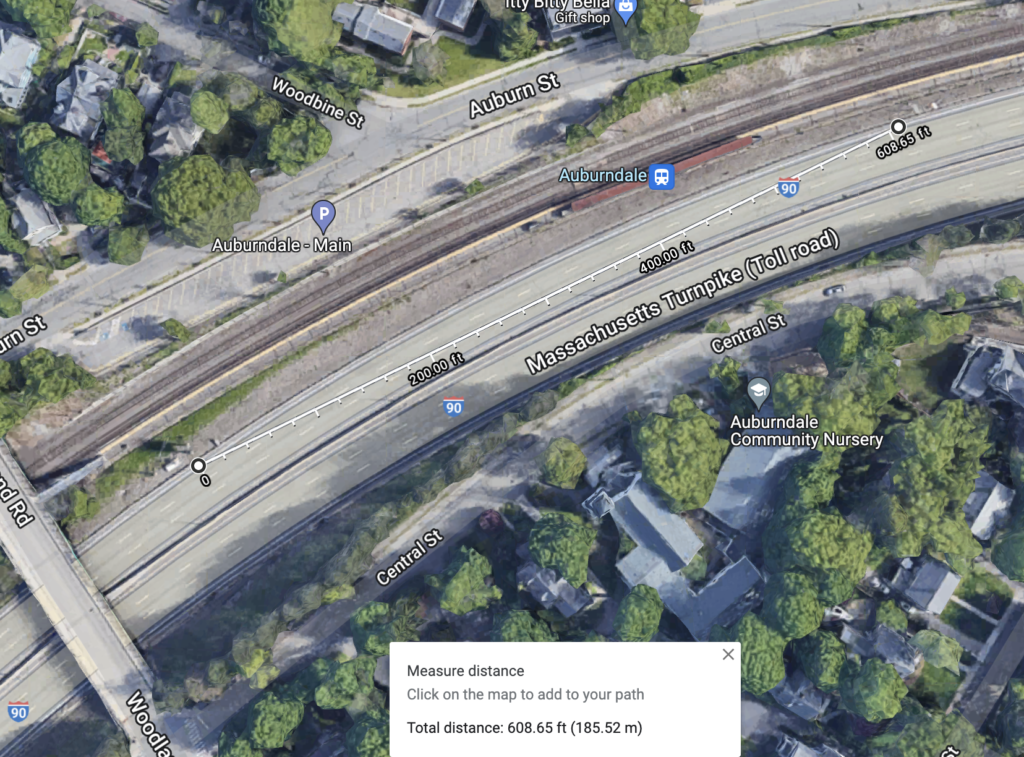

Alon’s other again-valid point is that sticking to a median means sticking to the curve of the roadway. Such an alignment may require constantly varying speeds, which is not exactly good for high speeds (see, for example, the Shore Line in Connecticut). But many roadways with wide medians are straight—or close to it—and would allow higher speeds. It’s hard to figure out curve radii using just Google Maps so I’ve created a bit of a cheat sheet. If we assume that highway lanes are 12 feet wide (in general, they are), we can draw a chord across a curve tangent to the second lane of the roadway using the measure distance tool (right click to activate it):

This example, in Newton, Mass. where the Turnpike is adjacent to the railroad, shows a 600 foot chord, which, if you do the trigonometry, traverses about 18˚ of a circle. US railroad curvature is measured as “degrees of curve per 100 feet”, which in this case is about 3˚. (I selected this example because I happen to know current speed limit here—55—and a resource with the curvature, although the original railroad may have been slightly straighter.) This corresponds to about a 575 meter radius. This can be extrapolated outwards as follows (approximately, see also this conversion table, and speed information here):

| Chord (feet) | Degrees | Radius (m) | Speed |

| 400 | 6.8 | 260 | real slow |

| 450 | 5.4 | 325 | |

| 500 | 4.4 | 400 | slow |

| 550 | 3.6 | 480 | |

| 600 | 3 | 575 | ~100 km/h / 60 mph |

| 650 | 2.6 | 675 | ~120 km/h / 75 mph |

| 700 | 2.2 | 780 | |

| 750 | 2 | 900 | |

| 800 | 1.7 | 1020 | ~150 km/h / 90 mph |

| 900 | 1.4 | 1290 | |

| 1000 | 1.1 | 1590 | |

| 1100 | 0.91 | 1925 | 200 km/h / 125 mph |

| 1200 | 0.75 | 2290 | |

| 1300 | 0.65 | 2690 | 250 km/h / 150 mph |

| 1400 | 0.56 | 3100 | |

| 1500 | 0.49 | 3575 | |

| 1600 | 0.43 | 4070 | 300 km/h / 186 mph |

Note that this can also be done in metric, and it can also be done by drawing chords on the inside of standard gauge railroad tracks. The calculator has information for both metric and imperial for both highway (two lanes) and rail tracks. (You can probably save a sheet as your own and change the values to pretty much anything else.)

Where median-aligned rail makes sense

Absent steep grades, roadways with sharp curves are not really suitable for true high speed rail. Even a road like I-95 in Connecticut has several 700-foot-chord curves which would limit speeds to about 80 mph in a few places, so the median might not be suitable. Still, a route along the Connecticut Turnpike would probably be much faster than the Shore Line: some of the sharpest curves have a wide median which could allow smoother curves, tilting trains could improve speeds, and the curves on the Shore Line are far more restricting. Several other Interstate highways in the northeast have similarly restrictive curves. And older and more urban highways often have narrow medians anyway.

That said, there may be other opportunities to leverage our wide medians in the US. Back when I blogged more regularly, I proposed routing South Coast Rail via a stretch of 495, which has a 100-foot-wide median. (This somehow pissed off people in Taunton, who didn’t want a good idea to get in the way of the current iteration of SCR.) The only appreciable curve this encounters on 495 is a 1200′ chord, so … fast (getting to 495 would be trickier). Whenever I drive up I-95 to New Hampshire I think about how straight and wide the highway is and, yes, it could support high speeds (but it doesn’t really connect anything). Out in California, I-5 on the west side of the Central Valley bypasses every population center between LA and San Francisco, but if California HSR had used its median instead of the debacle of going through the Central Valley cities, it may have allowed a much easier path to construction in the valley.

Sometimes “high speed rail” is thrown about by people with no idea what they are talking about. Like as a solution to I-70 traffic in Colorado. Certainly not in the too-narrow median, but also not along the highway with sharp curves. (In Europe they’d just dig a base tunnel, of course, the mountains in Europe are narrower.) And then you have the Connecticut NIMBYs saying to build an inland route along I-84 which … has hills, curves and development. The same ones who killed I-95 high speed rail because highways adjacent to historic sites are fine, but highways and trains next to historic sites are bad. (To be fair, the Lyme portion of I-95 has a narrow median, and 900m curve radii.)

Virginia S Line

Too often, railway planners don’t even consider the potential to use a highway median. The S Line project between Raleigh and Richmond is illustrative of this. It will use an existing railroad right-of-way, with many curves mitigated for higher speed operation, and new grade separations to create a fully grade-separated railroad (albeit not too many as it runs through a rural area). Most of the railway, especially in Virginia, runs parallel to I-85, which has a wide median (mostly 180 feet, a few sections near exits are closer to 80 but those have pre-built grade separation). Rather than re-engineering the parallel, abandoned rail line, a high-speed line could be laid in the highway median (the sharpest curve is about 0.5˚/3000m radius, which might limit speed at three short segments to about 165 mph, but given the width of the median the railroad could traverse a wider curve and maintain higher speeds.

The median here is mostly in a “natural” state, or about as natural as a treed-in area between two road carriageways can be. This would require considerable disruption of this “habitat” since it would leave only a small strip on either side (or, the trees would be removed entirely) which may have additional environmental burden compared to an existing, if long-abandoned, rail right-of-way. But since the parallel rail right-of-way will require several miles where the railroad will be rebuilt to be straighter, the highway median might be a more prudent choice, minimizing new grade separations and maximizing potential alignment for high speed.

Notably, this wouldn’t work as well in North Carolina. For whatever reason, while Virginia’s highway engineers left a wide median, North Carolina’s did not. The median narrows at the border to about 30 feet (portions of the road do have wider medians, but nothing like Virginia). It’s also more populated; the section between Henderson and Petersburg is only shown with one station in 920-person Norlina; the I-85 alignment would bring it closer to South Hill which, at nearly 5000 people, is the largest town in this 90-mile stretch by a wide margin (thus using the highway median won’t give up ridership). Meanwhile south of Henderson, the rail line goes through the fast-growing suburbs of Raleigh of Wake Forest which, notably, is not home to Wake Forest University (it moved 100 miles west to Winston-Salem in 1956). Following the highway alignment past Henderson would be more complicated and aim away from Raleigh and instead at Durham (serving both will require some amount of deviation, and there’s no reasonable right-of-way to Chapel Hill, but Richmond-Raleigh-Durham makes more sense since it then aims towards Charlotte and Atlanta; if there were ever demand a bypass of Raleigh could save about 25 miles). Further south in North Carolina, I-85’s median is often narrow, the roadway itself has more curves, and at one point crosses over itself for a mid-highway rest area. North Carolina’s highway engineers are cut from a different cloth.

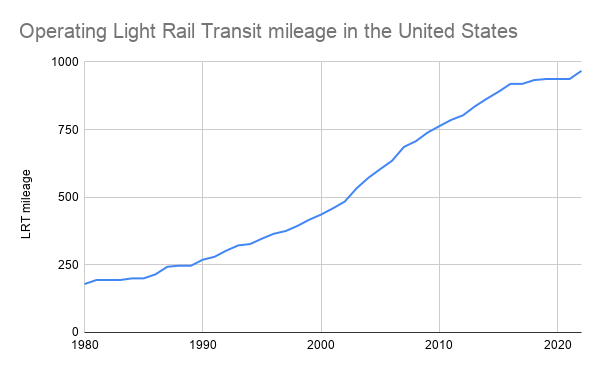

Brightline

Sometimes, planners use medians too well. Two high-speed rail projects which are in operation or planning are Brightline in Florida and Brightline West in California. Neither is without issues: Florida’s only has a few miles of high-speed operation (and it’s not so fast) but was built inexpensively along a very rural (and being Florida, straight and flat) highway. Where it does cross exit ramps, it required significant ramp redesigns or slower rail speeds (crossing Route 417 requires a 90 mph curve). Brightline in Florida has shown latent demand for mid-speed rail projects (although the Borealis train in the Upper Midwest has shown high demand using existing infrastructure).

Meanwhile, out west, Brightline’s next project is to connect Vegas and LA. And by Vegas I mean “near the strip, kind of” and by LA I mean “somewhere east of LA.” Downsides: lots of single track, the median isn’t as fast as it could be (curves, and some narrow sections). It won’t be faster than flying for most trips, and will only beat out driving at high-traffic times (which to be fair, because LA, is a lot of the time), and it will be hard to scale by speed or capacity, but it will be high speed rail, even if, going from exurbs to far-from-the-city-center and mostly single-tracked, it would be laughed out of Europe. (There are a number of European lines with stations far from city centers, but those are mostly smaller cities and towns mid-route, not major end-of-route destinations.)

There’s also the question of “can you build a new 220-mile right-of-way in four years?” Yes, the Florida version only took four years to build (if you discount some early work moving some exit ramps). But it was a simpler project: about 20% of the distance, no electrification, and much closer to an available workforce, with only one significant roadway reconfiguration (the Beachline east of I-95). If they can get this built, good, although hopefully it doesn’t encourage an American version of high speed rail with single tracking to save money but which inhibits future capacity.

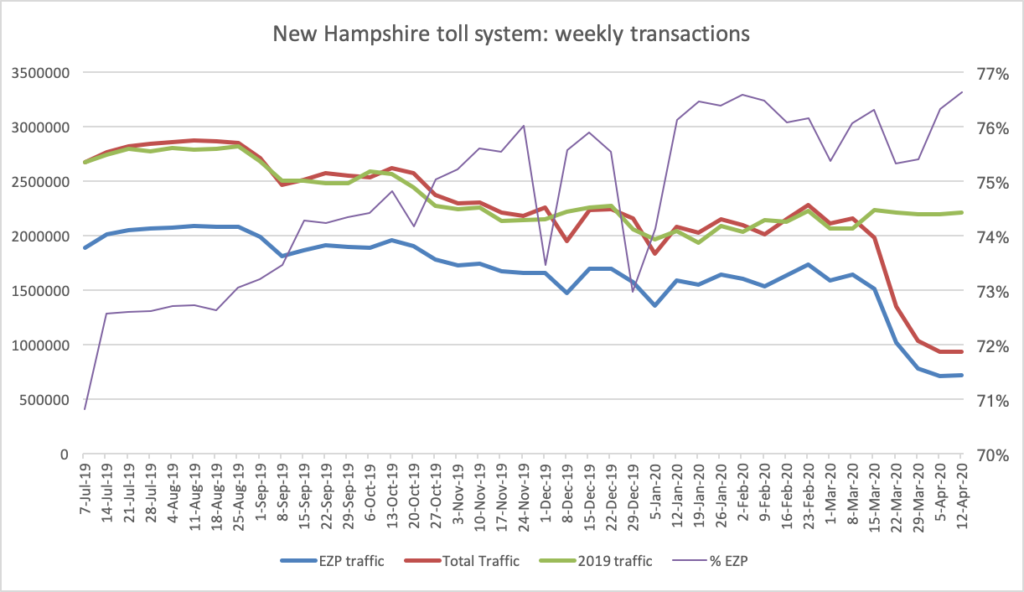

A local proposal: Cape Cod?

My interest was recently piqued by the continuing failure of the Cape Bridges project to garner necessary federal funding. Maybe the Feds are just not that interested in giving a couple of billion dollars to some bridges which are only at capacity a few days per year, and which MassDOT wants to widen (although they are nearly a century old). Of course, there is no mention of improving the rail link to the Cape, which currently takes 2:20 to get to Hyannis, an hour longer than driving without traffic (rare!).

In a civilized country, the Cape would be a transit-first destination. It has 220,000 year-round residents, 500,000 summer residents and significant additional short-term tourist traffic, and its 339 square miles include 100 square miles of National Seashore and military reserve. The two bridges crossing the canal create bottlenecks; when they were build in the 1930s, Barnstable County only had 32,000 residents. The Cape is a narrow peninsula which could be well-served by an arterial transit line, has many destinations with limited parking, and is most heavily-used in the summer, when bicycles should be a major transportation mode. Trips to the Cape include access to island ferry terminals: the islands have year-round populations of about 30,000, but nearly 10 times that in the summer, with the Steamship Authority providing half a million trips per month during peak season, plus other private ferries, with thousands of cars parked at mainland ferry terminals and minimal transit connections.

In America, transit on the Cape is barely an afterthought. Good transit would require a combination of useful local transit, safe bicycle facilities and various ways of discouraging traffic, a fast train to Boston, Providence and beyond, and special notice given to transporting people to the island ferry terminals since many of them have to park far away and board a shuttle already (so why not shift the shuttle of the other side of the bridge?). Density would help but wouldn’t be easy: one reason development on the Cape is so spread out: It was developed without a sewer system. (Building one ain’t cheap, and those chickens are coming home to roost.) As it is, there are commuter buses subjected to the same traffic as cars, a regional transit authority providing hourly service at best (although their route between Orleans and Provincetown does have the latest scheduled departure in the state, a 1:30 a.m. trip, and serves many workers priced out of the Lower Cape), and three train trips per week in the summer, which run on an existing commuter line, a straight line on the mainland at reasonable speeds before crossing the old lift bridge, and then at speeds charitably described as “pokey” on the Cape itself. CapeFlyer, which I wrote about in 2015, is a nice alternative for some but is not making much of a dent in traffic.

Imagine a high speed link from Middleborough to Hyannis. The line would transition to the median of 495 (sharpest curve: ~1500m) and where 495/Route 25 curves towards the Bourne Bridge, follow a power line right-of-way cross the Cape on a new fixed crossing where the canal splits two hills and is already crossed by power lines, eliminating any need for long ramps to attain grade. (More about this bridge below.) From there, the power lines lead to the Midcape Highway, which has a narrow median at first (but borders miles of state-owned military reserve) and eventually has a wider one. For most of the Midcape, the State owns a 400-foot-wide cross-section, and much of it includes a 100-foot dividing area between a service road and the highway itself. The worst curves there are also about 1500m, there are no long grades (although a couple of instances with grades above 3% which might need some earth moved), and the underlying topography is a glacial moraine so no need for significant blasting. So while the highest speeds might be off the table using a median alignment, averaging 100 mph—which would allow a trip from Middleborough to Hyannis in about 24 minutes and a trip from Boston in just over an hour—would be attainable.

I’m sure people would yowl about ruining the pastoral feel of the partially tree-lined highway median. And a train below a power line would harm the environment to no end. As for what to do with the existing railroad? With transit (and the trash train) moved to a new, faster corridor, it would be a great extension of the existing rail trail, since the portion east of Hyannis is relatively sparsely-populated and could be served by parallel highway-aligned stations. This would allow the popular rail trail to run from the canal to Wellfleet (beyond which the right-of-way is no longer intact, although the state is planning safer bicycle facilities along Route 6 to Provincetown).

Highway medians are certainly not always the answer for rail lines: they have to be wide, straight and flat enough and serve a desired path of travel. They also are suboptimal in urban environments, where the highway can be a barrier to potential rider access. Elsewhere in New England, there are few good examples:

- The Turnpike west of Boston is neither wide, straight or flat, and improving the parallel existing railroad is a better alternative.

- I-95 to Providence has a wide median but is paralleled by one of the few high speed rail segments in the country.

- In Connecticut, the highway might be useful to bypass the curvy shore line in the eastern part of the state, but is shoehorned in amongst sprawling suburbs further west, where improvements to the existing New Haven line are probably a better investment.

- I-91, I-84: hilly, curvy, narrow, or all of the above.

- I-95 north of Boston is straight, wide and flat and would make a good segment of a higher-speed line to New Hampshire and Maine … if only it connected anywhere near the existing railroads.

- Elsewhere in Northern New England: curves and mountains, although the 15-year, nearly-a-billion-dollar reconstruction of I-93 in New Hampshire may have left room so as not to preclude an eventual rail line.

Given enough width and straight enough corridors and a good route profile, they can provide a good alignment for some new medium- to high-speed corridors. This requires both wide-enough medians (rare in Europe and hardly a given in the US) and straight- and flat-enough alignments. When these ingredients come together, highway medians can provide a potential lower-cost, politically expedient means of building a railroad.

Oh, about that Canal bridge …

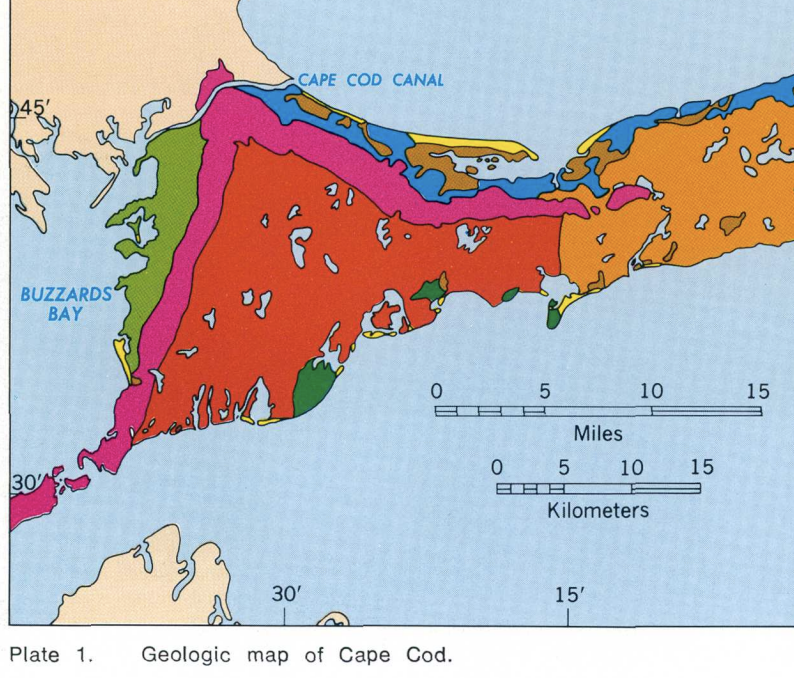

It’s worth remembering that Cape Cod is a terminal moraine and related glacial outwash which was formed at the end of the glacial ice sheets which covered New England in the not-too-distant past. (So are Long Island, Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard, here is a useful publication.) Notably, as shown on the map below, two moraines from glacial ice lobes meet near the canal, creating a narrow cut with steep hillsides on either side (magenta).

Between the tops of the hills at this point the canal and its cut is about 2100 feet wide (in this image the power line supports sit on top of the nearby hills). The canal itself is 700 feet wide, although the navigable portion is just 480 feet; the Bourne and Sagamore bridges’ longest spans are 616 feet with supports in the edge of the canal. 600 feet is not a particularly remarkable length for a bridge: the Hell Gate Bridge has a span of nearly 1000 feet (and miles-long approach spans, something which wouldn’t be necessary here).

In Germany, the recently-completed Erfurt-Nuremburg high speed line has several bridges of interest, the longest of which are the Grümpentalbrucke (Germany finally has some streetview) and the Talbrucke Froschgrundsee, each a 270 meter span. The Talbrucke Froschgrundsee is 65m in height (it’s unclear if this is to the top of the bridge or clearance below; in either case, much higher than the Cape Cod Canal clearance of 41m) and cost 16 million Euros to build in 2008 (adjusting for inflation and currency, about $36 million today).

Even more impressively, the Almonte and Tajo bridges near Cáceres in Spain are both more than 300 meters long and 70 meters high. These bridge were built over a reservoir with strict environmental guidelines which didn’t allow any construction in the water itself. Also, these concrete arch bridges are visually interesting, and would be a dramatic addition to the landscape and possibly a net positive (especially if the power supply were put into a conduit on the bridge and the power line towers removed).

Closer to home and present, the new bridge over the Genessee River in Letchworth State Park in New York was completed in 2017 for $71 million (for a single track). The current lift bridge to the Cape is just as old as the fixed highway bridges, and replacing it with a fixed, higher speed crossing could pay long-term dividends.

Why not a tunnel? A tunnel wouldn’t take advantage of the topography, and because it would have to clear well under the canal, it would require a long approaches on either side. On the mainland side, it would need to go from about 100 feet above ground level to 100 feet below, and on the Cape side from 200 feet above to 200 feet below. Even with a 3% grade, this would require about a mile and a half on the mainland side and two and a half miles on the Cape side, plus half a mile under the canal, meaning a five mile tunnel versus a half mile bridge.