Boston has a bus problem. Beyond narrow, congested roads and

routes which traverse several jurisdictions—in some cases half a dozen in the

span of a single mile—there are simply not

enough buses to go around. At rush hour, some MBTA bus routes only have

service every 20 to 30 minutes, despite crush-capacity loads on the vehicles

serving them. To add significantly more service would require the MBTA to add

additional buses to the fleet, but procurement of new vehicles is not the rate-limiting

factor. The larger issue is that the MBTA’s bus storage facilities are

undersized and oversubscribed, so adding new buses would require adding

additional storage capacity to the system, a high marginal capital cost for any

increase in service.

Before doing this, the MBTA may be able to squeeze some

marginal efficiency from the system. All-door boarding would reduce dwell

times, speeding buses along the routes. Cities and towns are working with the agency to

add queue jumps, bus lanes and signal priority, steps which will allow the

current fleet to make more trips over the course of the day. Running more

overnight service would mean that some number of buses would be on the road at

all times of the day and night, reducing the need to store those buses during

those times (although they might need to be serviced during peak hours, and may

not be available for peak service). Still, all of this amounts to nibbling

around the edges. Improving bus service may result in increased patronage, and

any additional capacity wrung out of the system could easily be overrun by new

passengers. The MBTA’s bus system is, in essence, a zero-sum game: to add any

significant capacity, the system has to move resources from one route to

another: to rob Peter to pay Paul.

Furthermore, Boston’s bus garages are

antiquated. In the Twin Cities—a cold-weather city where a similarly-sized bus

fleet provides half as many trips as Boston (although about the same number of

passenger miles)—nearly every bus garage is fully-enclosed, so buses don’t sit

outside during cold snaps and blizzards as they do in Boston. Every facility

there has been built since 1980, while several of the MBTA’s bus yards date to

the 1930s; some were originally built for streetcars. Boston

desperately needs expanded bus facilities, but it also needs new bus garages:

the facilities in Lynn, Fellsway and Quincy are in poor condition, and the

Arborway yard is a temporary facility with very little enclosed area.

However, what Boston’s bus yards lack in size or youth they

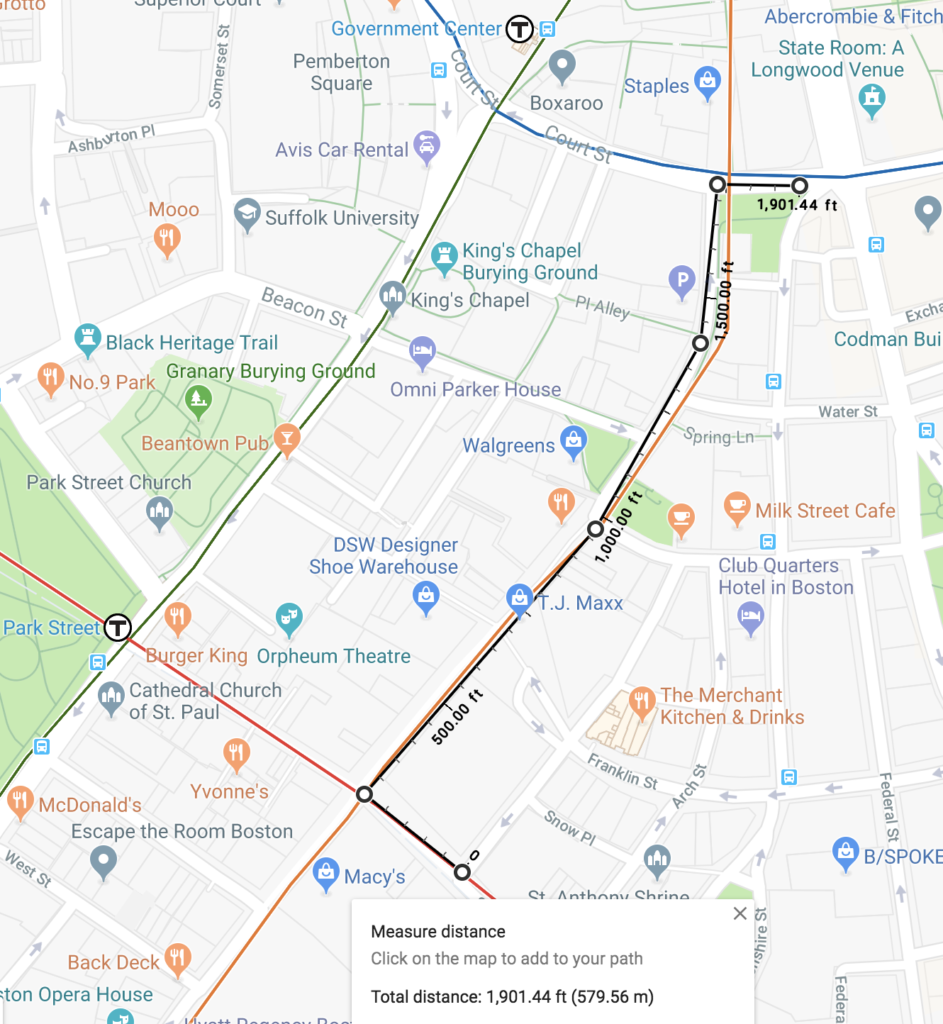

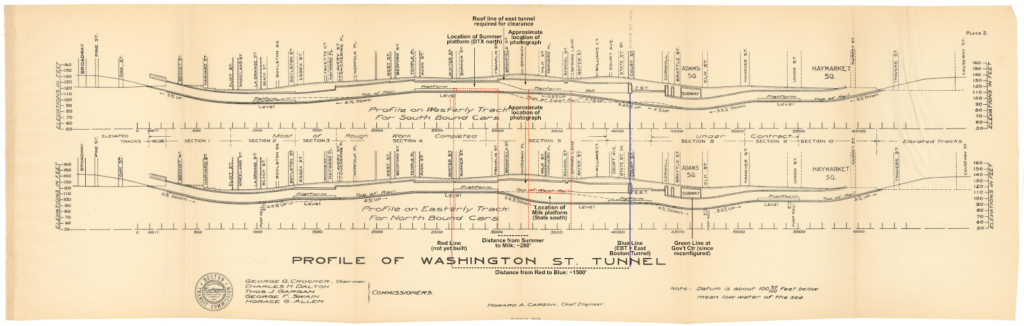

make up for in location. The MBTA bus system is unique in the country in that there is no bus service through downtown: nearly every trip to the city requires a transfer from a

surface line to a rapid transit line. In the past, elaborate transfer stations

were built to facilitate these transfers, with streetcar and bus ramps above

and below street level (a few vestiges of this system are still in use, most

notably the bus tunnel at Harvard), with bus routes radiating out from these

transfer stations. When the Boston Elevated Railway, the predecessor to

the MBTA, needed to build a streetcar yard, they generally built it adjacent to

a transfer station, and thus adjacent to as many bus routes as possible. Many

of these have become today’s bus yards, and the MBTA has some of the lowest

deadhead (out of revenue service) mileage to and from the starts of its routes.

From a purely operational standpoint, this makes sense: the

buses are stored close to where they are needed. But from an economic

standpoint, it means that the T’s buses occupy prime real estate. Unlike rail

yards, which need to be located adjacent to the lines they serve, bus yards can

be located further away. While this introduces increased deadhead costs to get

the buses from the yard to the route, it frees up valuable land for different

uses. In recent decades, the T has sold off some of its bus garages, most

notably the Bartlett Yard near Dudley and the Bennett Yard near Harvard Square,

which now houses the Kennedy School. The downside is that the T currently has

no spare capacity at its current yards, and needs to rebuild or replace its

oldest facilities.

While the agency has no concrete plans, current ideas

circulate around using park-and-ride lots adjacent to rail stations for bus

storage, including at sites

adjacent to the Riverside and Wellington stations. The agency owns these

parcels, and the parking can easily be accommodated in a nearby garage. The

issue: these parcels are prime real estate for transit oriented development,

and putting bus garages next to transit stations is not the best use of the

land. Riverside

has plans in place, and Wellington’s parking lot sits across Station Landing, which has

hundreds of transit-accessible apartments.

In addition to what is, in a sense, a housing

problem for buses, the Boston area has an acute housing problem for people. The

region’s largest bus yards are adjacent to Forest Hills, Broadway and Sullivan

Square: three transit stations with easy downtown connections. These issues are

not unrelated: there are few large parcels available for housing or transit

storage (or, really, for any other use). If the region devotes land to housing,

it may not have the ability to accommodate the transit vehicles needed to serve

the housing (without devolving the region in to further gridlock). If it uses

transit-accessible land for storing buses, it gives up land which could be used

for dense, transit-accessible housing. What the transit agency needs are sites

suitable for building bus depots, on publicly-owned land, and which would not

otherwise have a high-level use for housing.

Consider a bus maintenance facility: it is really something

no one wants in their back yard. And unlike normal NIMBYism, there actually

some good reasons for this: bus yards are noisy, have light pollution, and

operate at all times of day, but are especially busy for early morning

operations. An optimal site for a bus yard would be away from residences, near

highways (so the buses can quickly get to their routes), preferably near the

outer ends of many routes, and not on land which could otherwise be used for

transit-oriented development. It would also avoid greenfield sites, and

preferably avoid sites which are very near sea level, although if necessary

buses can be stored elsewhere during predicted seawater flood events.

The MBTA is in luck. An accident of history may provide

Boston with several locations desirable for bus garages, and little else. While

most sites near highways don’t have enough space for bus yards, when the regional

highway system was canceled in the early 1970s, several interchanges had

been partially constructed, but were no longer needed. While portions of the

neighborhoods cleared for highways have been, or could be, repurposed in to

developable land, the “infields” of highway ramps is not generally ripe for

development. Yet they’re owned by the state, currently unused, convenient to highways

and unlikely to be used for any other purpose. For many bus routes, moving to

these locations would have a minimal effect on operation costs—deadhead pull-in

and pull-out time—and the land will otherwise go unused. Land near transit

stations is valuable. Land near highways is not.

Building bus yards in these locations would allow the T to

add vehicles to the fleet while potentially closing some of its oldest,

least-efficient bus yards, replacing them with modern facilities. They wouldn’t

serve all routes, since many routes would still be optimally served by

closer-in yards with shorter deadhead movements to get the buses to the start

of the route. (To take this to an extreme: it would be very cheap to build a

bus yard at, say, the former Fort Devens site, but any savings would be gobbled

up by increased overhead getting the buses 35 miles to Boston.) Highway ramps

are optimal because it allows buses to quickly access the start and end of

routes, many of which, by history and happenstance, are near the highways

anyway.

Most importantly: moving buses to these locations would enhance

opportunities for additional housing, not preclude it. Building thousands of

new housing units adjacent to transit stations pays dividends several times

over. It increases local tax revenues and also creates new, fare-paying transit

riders without the need to build any new transit infrastructure. Finally, by

allowing more people to use transit for their commutes, it reduces the growth

of congestion, allowing people driving—and people riding transit—to move more

efficiently.

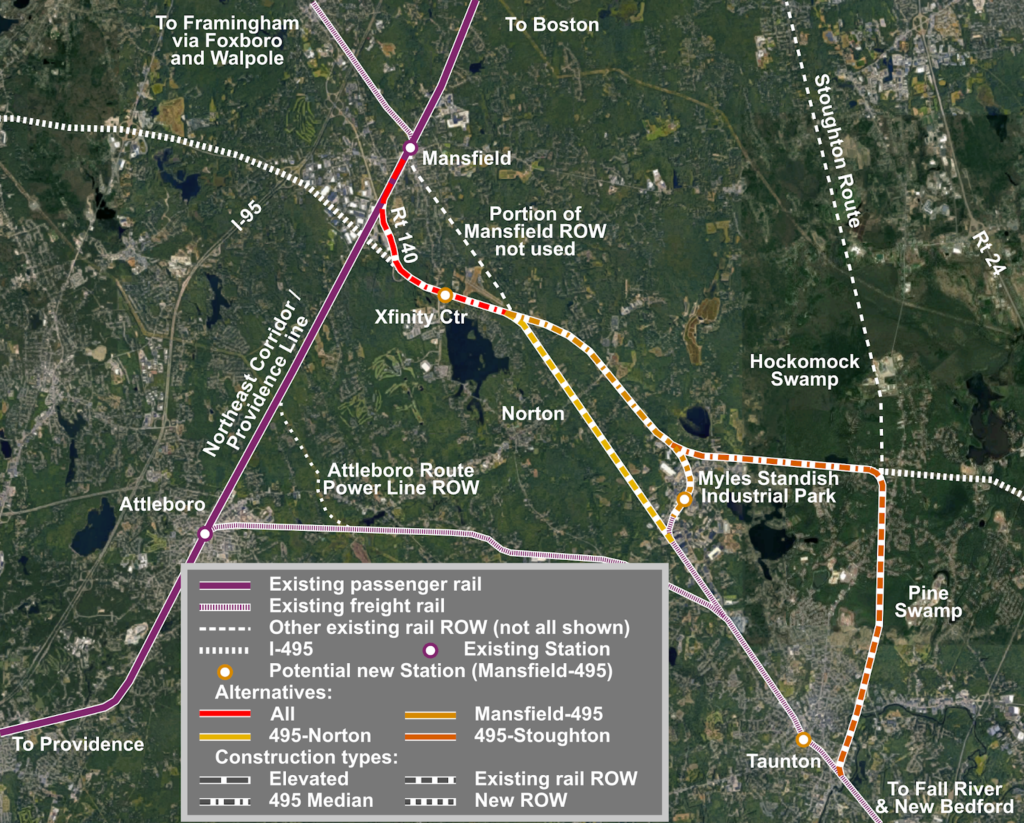

Specifically, there are five highway sites in the region

which could be repurposed for bus fleet facilities:

- Quincy, in between the legs of the

Braintree Split - Canton, on the aborted ramps of

the Southwest Expressway - Weston, where the new all-electric

tolling has allowed for streamlined land use - Burlington, in the land originally

planned for the Route 3 cloverleaf - Revere, in the circle where the

Northeast Expressway was originally planned to branch off of Route 1 through

the Rumney Marshes.

In more detail, with buses counts from the MBTA’s 2014

Blue Book. These are in-service buses required, so the total number of buses

at each location, accounting for spares, would be 15 to 20 percent higher. The

system currently maintains approximately

1000 buses.

Quincy (67 buses)

All 200-series Quincy Routes

The current Quincy garage serves the

200-series routes, with a peak demand for 67 vehicles. The current garage is in

need of replacement. The current yard takes up 120,000 square feet on Hancock

Street, half a mile from Quincy Center station. This could easily be

accommodated within or adjacent to the Braintree Split, with minimal changes to

pull-out routes. Serving additional routes would be difficult, since the

nearest routes run out of Ashmont, and pull-out buses would encounter rush hour

traffic, creating a longer trip than from the current Cabot yard.

Canton (35

buses)

Routes

24, 32, 33, 34, 34E, 35, 36, 37, 40

This would be a smaller yard and would

probably only operate during weekdays with minimal heavy maintenance

facilities, but would reduce the overall number of buses requiring storage

elsewhere.

Weston (71 buses)

Routes 52, 57, 59, 60, 64, 70/70A, all

500-series express bus routes.

With the recent conversion to all-electronic

tolling on the Turnpike and different ramp layout, the land is newly-freed,

plentiful, and many buses serving this area have long pull-out routes from

Boston. The portion between the two branches of the Turnpike and east of the

128-to-Turnpike ramp is 500,000 square feet, the same size as the Arborway

Yard, and there’s additional room within the rest of the interchange. Without a

bus yard west of Boston, any route extending west or northwest would benefit

from this yard.

Burlington (50 buses)

Routes 62, 67, 76, 77, 78, 79, 134, 350, 351,

352, 354

These routes utilize serve the northwest

suburbs, but most are served by the Charleston and Bennett divisions in

Somerville. Most routes would have significantly shorter pull-outs.

Revere (157 buses)

The two oldest bus garages north of Boston are

Lynn and Fellsway, which account for a total of 125 buses and about 200,000

square feet. They are both centrally-located to the bus network, so moving

buses to the 128 corridor would result in longer pull-outs, except for a few

routes noted above. However, the circle where Route 1 turns northeast and the

Northeast Expressway was originally planned and graded towards Lynn across

Rumney Marshes has 750,000 square feet, and the extension towards the marshes

more. The fill is far enough above sea level to not worry about flooding, and

grade separation allows easy exit and entry on to Route 1. Some buses may make

sense to base at the Route 3 site, particularly the 130-series buses. In

addition to the Lynn and Fellsway buses, this site could take over for many

routes currently operating out of the Charlestown yard, freeing up capacity

there for other uses.

Other routes served by the Charlestown yards

would face somewhat longer pull-out times from Revere, but given the development

potential in Sullivan Square, the T could consider downsizing the yard facility

there and moving operations to a less valuable site. This site, at more than

one million square feet, could likely replace the Charlestown bus facility

entirely.