The Red Line derailment didn’t look too bad at first. The train stayed upright, there were no major injuries, and it appeared that the train would just have to be rerailed, the track repaired, and normal service would resume. The T did an excellent job setting up what skeleton service they could to bypass the site, providing rail service to Braintree and Ashmont without resorting to trying to put ten thousand people per hour on buses which would tie up half of the bus fleet (which is otherwise occupied at rush hour). It seemed the incident had happened in a relatively good location, one of the few where there was some redundancy, as passengers could just transfer from one side of the station to the other.

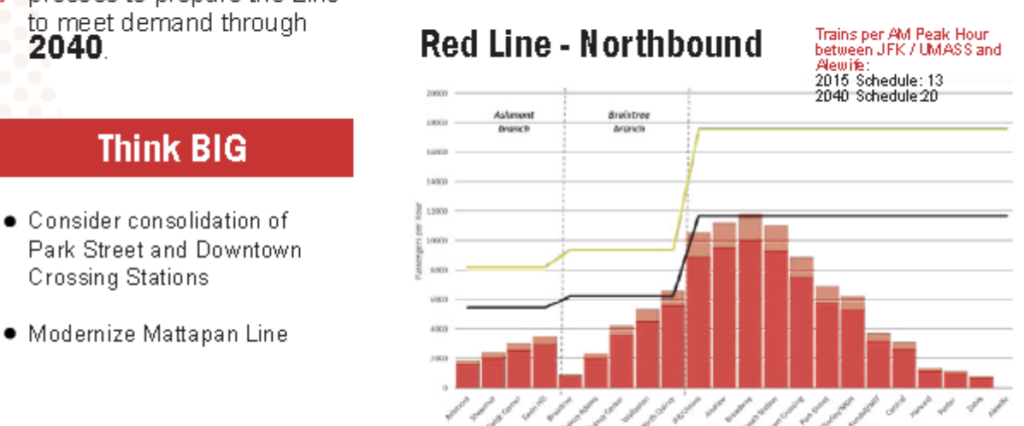

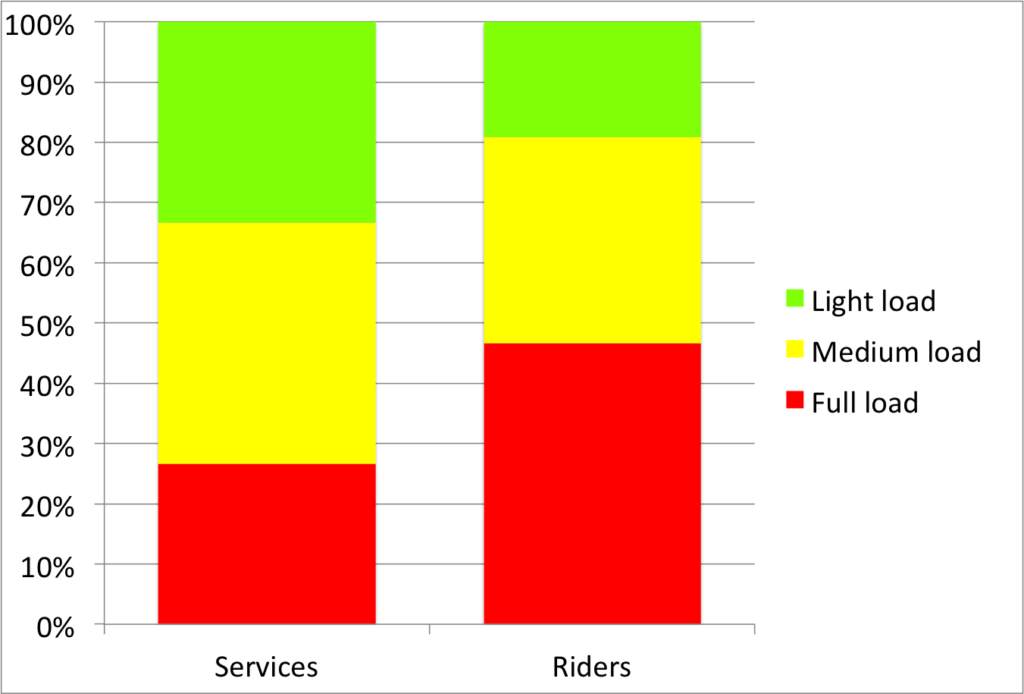

On Wednesday we found out just how bad it was. With the railcar finally removed (it is rumored that the reason the crane wasn’t placed on the Columbia Road bridge as originally proposed was because DCR didn’t know the maintenance level weight limit of the bridge and dropping the bridge on the Red Line would have been even worse) we saw what it hit. The little building next to the tracks housed the signal equipment for not only Columbia Junction—often dubbed Malfunction Junction, and that’s when the signal system works!—but several miles of track in either direction. Now the 14 trains per hour normally scheduled across the line—which are barely enough to handle rush hour traffic—are reduced to four to six, for the foreseeable future. It turns out that this derailment didn’t happen in a good location, but a bad one.

Signal systems are complex and bespoke, so a full replacement may take months or years to procure, if not longer. In 1996, when the Muddy River flooded into the Green Line, normal operations didn’t resume for months, and fixes for the system itself took years, and $40 million in repairs. The T now closes the Fenway portal during heavy rain events every few years to prevent a repeat of that situation. However, the proximate cause—flooding from the Muddy River—was a bigger issue: a century ago, the river was relocated in to culverts below Park Drive, and with only so much space in the culverts, it would back up along the Riverway during heavy rains, overtop the levee, and, once the D Line was built in 1959, pour in to Kenmore (which had happened in 1962 as well). This was eventually fixed as part of a 20-year project spearheaded by the Army Corps of Engineers and multiple other agencies, and with the new drainage in place, future flooding of the MBTA is less likely. Instead of continuing with the same reactionary system—where floodgates and sandbags were required every few years, and if they didn’t work, as occurred in 1996, the results would be catastrophic—we changed the larger ecosystem to one which would prevent the problem in the first place.

The Red Line derailment should serve as a similar wake-up call. Despite Governor Baker’s repeated calls for no new revenue, simply fixing the system we have won’t work. We—and I’m putting this in italics—can not continue to double down on the same system we have and expect different results. In the short term, this is going to require we invest in the system to make it more efficient and more resilient. In the long term, addressing wider problems will create the sort of system that will pay dividends when things like this week’s derailment occur less frequently and, when they occur, have less impact.

A short history of Cabot Yard and Columbia (a.k.a. Malfunction) Junction

The Red Line was the last of Boston’s subways to be built. The original segment operated between Harvard and Park and it was eventually extended, as the “Cambridge-Dorchester tunnel“, to Ashmont. At first, the only yard facility was on the north end of the line at the Eliot Shops, a complex of yards and shops tucked between Harvard Square and the Charles River, which is home to the Kennedy School today. When the line was extended in the 1920s, it added another yard—Codman Yard—past Ashmont station. For the next 50 years, the line would operate quite simply: trains would pull out of a yard beyond the terminal, service the line, and then pull into the yard at the terminal. This is optimal: the line requires no mid-line switches, and every train coming in or out of service simply pulls in to the first stop.

The 1970s and 1980s changed that. In 1965, the T purchased the Old Colony right-of-way to build an extension to Quincy and Braintree. This was originally planned to be an independent, express line (which is why there is no Braintree station at Savin Hill or Neponset) which would terminate at South Station. Eventually, it was aligned to be part of the Red Line, which required a new junction where the lines split at Columbia Road.

More importantly, it needed somewhere to store and service the cars. The Eliot Shops were small, cramped, and sat on valuable land eyed by Harvard for years. The T gave the land to Harvard in 1966 but needed to find a new location for its yards. The Ashmont Branch was out: Codman Yard was surrounded by housing. Braintree didn’t want a rail yard at the end of the line and blocked efforts for a yard there, so the T finally paid the Penn Central for the freight yards in South Boston to store Red Line cars. This was by no means their first choice: in order to access the line, trains would have to traverse nearly two miles of non-revenue track to get to JFK-UMass, and would then have to run the rest of the way back to Braintree to begin their inbound trips. (A small yard—called Caddigan, in keeping with an apparent rule that all Red Line facilities must begin with a hard C—exists past Braintree, but it can only store a few cars.)

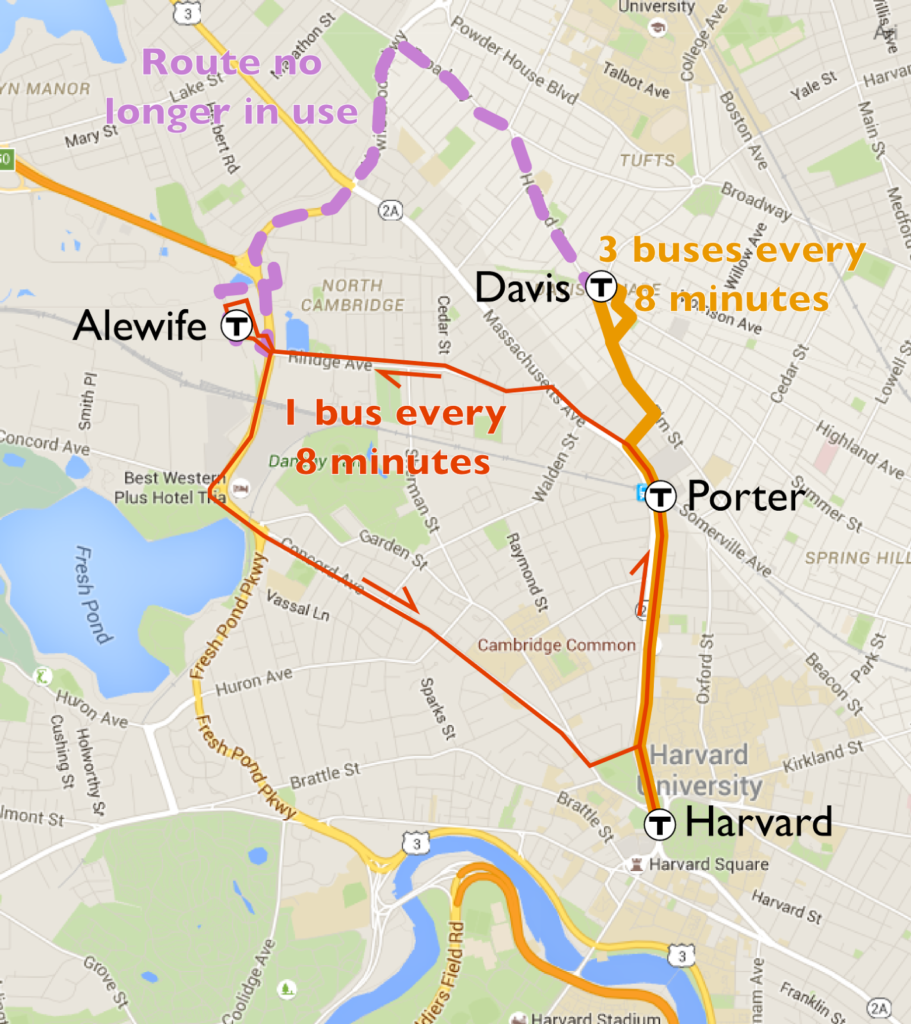

This issue was exacerbated in the 1980s when the Red Line was lengthened once again. The line was extended from Harvard to Alewife, but was originally slated to go beyond. As late as 1977, the line was planned to Arlington Center (with an eventual extension) and the decision was made to curve the line past the Alewife station to aim towards Arlington, forgoing the ability to build a yard on then-vacant land just west of Alewife. The next year, the town decided it didn’t want rail service, but the deed was done, and no terminal was available at the north end of the line, either. (This was related to me by Fred Salvucci, who had some choice words for Arlington and Cambridge about this. I’ve written about an idea to build a yard below Thorndike Field beyond Route 2 to mitigate the terminal issues at Alewife.)

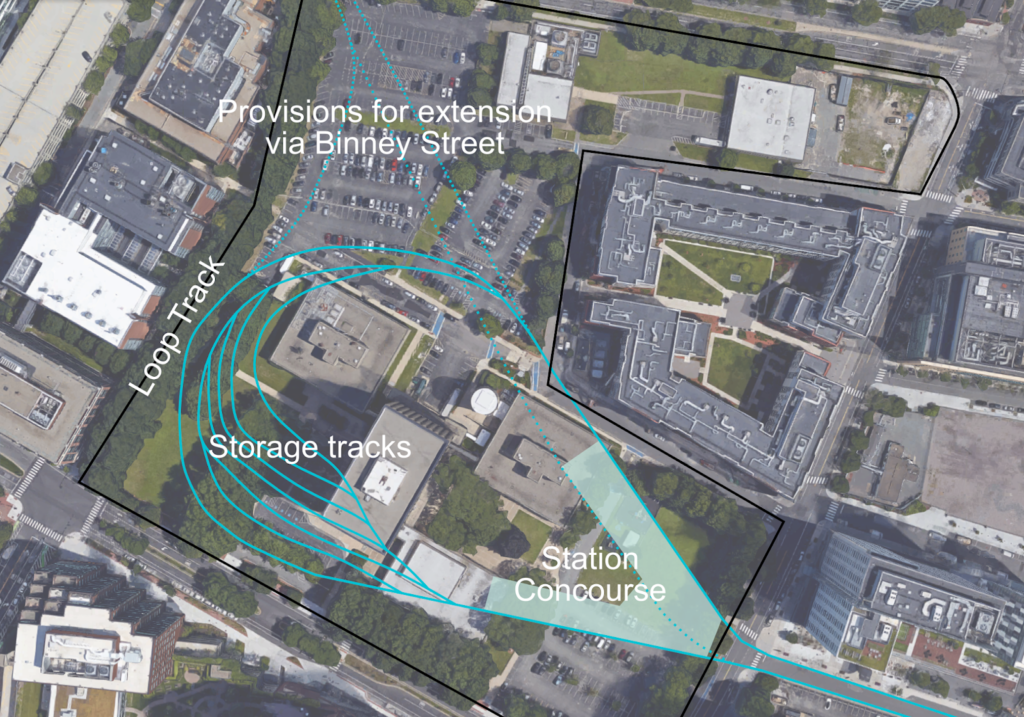

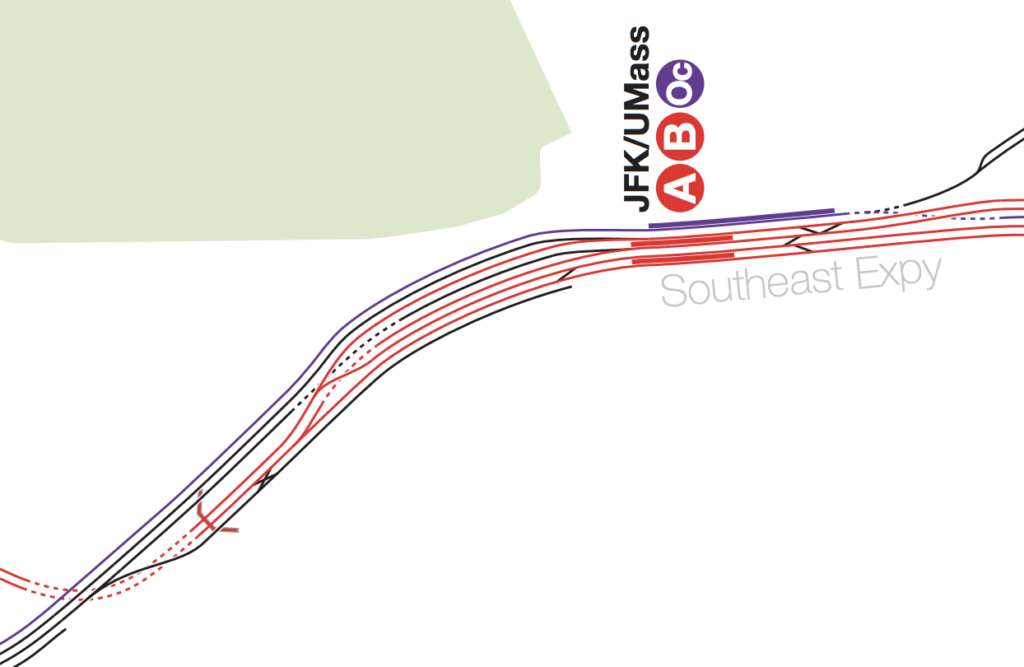

So Cabot is it. It serves most of the trips for the Red Line and is the only maintenance facility. It sits less than a mile from Downtown and the Seaport on what is undoubtedly valuable land. (The nearby MacAllen Building and its neighbor have 279 condos; the two northernmost portions of Cabot are about three times as big.) And Cabot is the main reason that the location where the train derailed—Malfunction Junction—is as complex as it is. In fact, the switch where the train derailed has nothing to do with splitting apart the branches of the Red Line, but rather a switch for a “yard lead” allowing trains to return to Cabot. The entire complex is conceptually designed quite well: it creates a series of “flying junctions”—not just between the two branches, but also for trains between the Braintree line and Cabot (most Ashmont trains operate out of Codman so therefore don’t require as frequent movement). This requires a series of complex switches and flyovers, but means that operationally no train ever has to cross another line.

|

| Columbia Junction. North (towards Downtown Boston) is at the left. A snippet of a full MBTA track map (the best MBTA track map!) which can be found here. |

But Columbia Junction, as built, is a known problem spot and frequent cause of delays, and this doesn’t change the fact that Cabot is in the wrong geographic location for a rail yard. In Chicago, nearly every yard is at the end of the line, or close by (the last mid-route yard—Wilson—was decommissioned in the ’90s in favor of a yard at Howard). New York, DC and San Francisco rely on yards mostly built on the outlying portions of the line. The T specializes in mid-route yards for the Orange and Blue lines (Wellington and Orient Heights), but both are located adjacent to the line, not miles away.

Thus, Cabot Yard has four major problems:

- It connects to the wrong part of the line for a rail yard

- It is not even close to said line

- Where it connects to the line it requires a series of complex switches

- It sits on otherwise valuable land, probably the most valuable land of any heavy rail yard (setting aside Commuter Rail yards downtown which, while in sensible locations operations-wise, sit on huge parcels of valuable land and which could be freed up with a North-South Rail Link, but that’s the topic of another post entirely).

I wrote last year about how the optimal location for bus garages is probably on state-owned land adjacent to highways, rather than next to transit stations as the T is proposing at Wellington and Riverside. No one wants a bus yard in their backyard, and building bus lots next to train stations instead of transit-oriented development is doubly wrongheaded. While rail yards are more location-constrained than bus yards (since they have to physically connect to the railroad) there is some potential to leverage the same sort of arrangement of land in Braintree for the Red Line.

If the Braintree branch were being built today, a logical location for a yard would be at what is currently the Marketplace at Braintree development. When the line was built, this was an active rail yard (a small portion still is a freight yard), and the Red Line was built on the “wrong side” of the tracks to access this parcel. Using it today would require not only nearly $100 million to buy the land and businesses, but nearly-impossible negotiations to somehow reimburse Braintree for that commercial tax base. The site south of the Braintree garage has less value (about $25 million) but is also on the “wrong side” (the Red Line is east of the Commuter Rail to allow access to what is now the Greenbush Line) and would require some sort of flyover or duck-under to gain access, while being slightly smaller than Cabot. Further south, there are some potential sites, but these would require longer lead tracks and have potential wetland impacts and NIMBY implications.

|

| A map showing the locations of the sites mentioned above. |

There is a site near Braintree, however, which would have no acquisition cost, since the state already owns it. It would have no impact on the tax base, since it has no assessed value. It will never be suitable for residential or commercial development, since it sits inside a highway interchange. It is, of course, the land within the Braintree Split. The land in the “infield” of the Braintree Split amounts to about 70 acres, which is nearly four times the size of Cabot Yard. The interchange is a “Directional-T” interchange, and designed so that at its center, three roads cross each other at the same point. The are, from lowest to highest, the mainline route from 93 north to 93 north, from Route 3 north to 93 south, and from 93 south to Route 3 south. This is important, because it would impact how a potential rail yard could be linked together.

None of the parcels bounded by the Braintree Split is as large as the entirety of the Cabot Yard (about 18 acres), although Cabot itself is split roughly evenly by the 4th Street bridge between the maintenance facility and the storage yard. Four of the sectors are roughly the same size, two are significantly smaller. Given the topographical constraints, it would be easiest to link together the 16 and 12 acre parcels. The map below shows the parcels within the Split, the size of each in acres, and, superimposed with dashed lines on the 16- and 12-acre parcels, the outlines of the Cabot shops facility and storage yard, respectively, with dashed lines.

|

| Braintree Split parcels, with the Cabot shops and yard superimposed on the 16- and 12-acre parcels. |

The Braintree Split is not as optimally located as, say, the site south of the Braintree station. It’s a bit further from the Red Line, and not at the end of the line, so some deadhead movement would be required to reach the terminal. But it’s considerably closer to both the end of the line in Braintree and to the line itself. The closest portion of the 12-acre parcel is only about 0.25 miles from the Red Line tracks, although there are some roadway ramps in between. (There are plenty of examples of rail yards interacting with highways, like the WMATA West Falls Church yard in Virginia, 98th, Rosemont and Des Plaines yards in Chicago, and South Yard in Atlanta.

It is worth noting that Braintree Split isn’t exactly flat. If you drive from 93 south to Route 3 south, you descend from an elevation of 180 feet down to 40 feet. Rail yards have to be flat (so, you know, unmanned trains don’t roll away if their brakes fail), and rail grades, even for a rapid transit line, should be at most two or three percent. Given that the 12-acre parcel is lower than the 16-acre parcel, the two would have to be used for separate facilities, but there is no reason that the 12-acre parcel couldn’t host a storage yard with shop facilities at the 16-acre parcel. In fact, the 12-acre site is better suited for a storage facility (since it is long and narrow) while the 16-acre site would have plenty of room for a maintenance facility and potentially additional storage tracks, which might be necessary if the Red Line were one day improved to offer service every three minutes.

This would require about 1400 feet of lead tracks from the Red Line to the storage yard, and no new land acquisition as all would be built on land already owned by the state. The yard lead would extend flat over the first set of ramps and Route 3 north (the Red Line climbs at about a 3% grade out of Quincy Adams to cross over the Old Colony Commuter Rail), and would then descend down to the level of Route 3 to pass over the northbound Burgin Parkway ramp and under the southbound one. There it would split in to two, with one set of tracks leading to a level storage facility and the other extending up to the maintenance facility further north. Access to the maintenance yard would be available from near the zipper lane facility just north of the split, although parking might be better provided on the side of the highway with a pedestrian bridge for workers to access the yard. If funds were available from nearby developers, these walkways could even allow a station to provide better access to nearby office buildings to provide a shuttle service from Quincy Adams or Braintree.

Simplifying Columbia Junction and Savin Hill

There are other knock-on effects to simplifying Columbia Junction and relocating Cabot Yard.

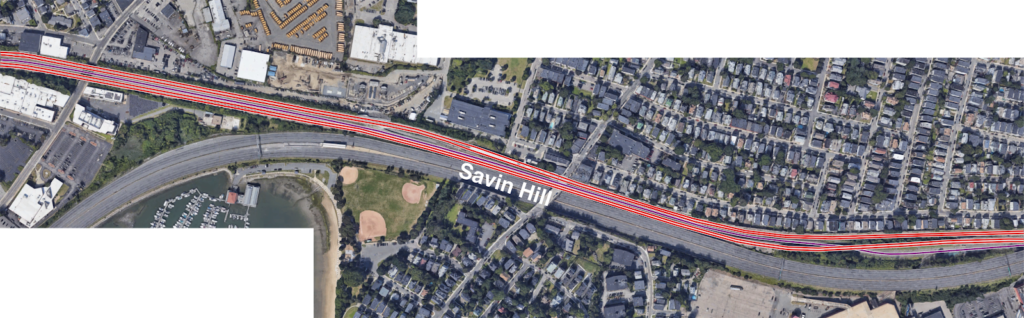

In addition to the Old Colony Commuter Rail line running through a single-track bottleneck south of JFK-UMass (which is part of the reason only a few extra trains can be run at rush hour), there is a bottleneck on I-93 there as well. In 2012, CTPS developed a concept to add HOV lanes to I-93 and a track to the Old Colony lines (thereby removing a single-track bottleneck) near Savin Hill by burying both the Old Colony and the Red Line for the better part of a mile. Yet this concept would likely rival the Allston I-90 project in complexity and cost.

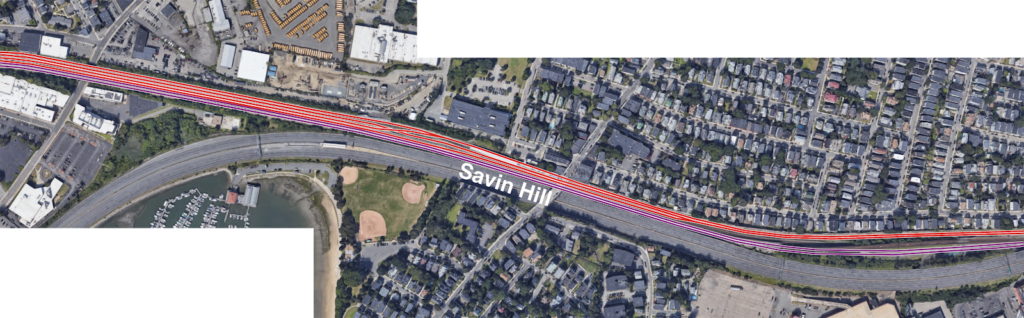

With South Coast rail now being (wrongly, in my opinion) pushed down the Old Colony Line, the FMCB has considered a similar plan. Yet this is based on the false premise that four tracks need to be provided to JFK/UMass, which is mostly required to allow access in and out of Cabot Yard from the Braintree Branch. Without the need to access Cabot Yard via a flying junction, there is no need for four tracks through Savin Hill: by combining the two Red Line branches south of Savin Hill, one of the existing Red Line tracks could be used for Commuter Rail through the Savin Hill bottleneck with only some minor modifications, at least relative to the state’s incoherent plan. In addition, by replacing Cabot Yard with a facility in Braintree, the entirety of “Malfunction Junction” could be replaced by two switches, one to split the southbound main line in to two branches, and another to combine the two northbound tracks together.

The sketches below show the current configuration of the railroads adjacent to Savin Hill, and a proposed concept. The proposed concept would have outbound trains stop at Savin Hill, but inbound trains on the Braintree Branch (which has less capacity) would bypass Savin Hill and merge in past the station (as they do today), although it could certainly be realigned to allow all trains to serve Savin Hill. North of this junction, the Red Line would operate as a simple, two-track railroad through to Andrew and on to Downtown and Alewife. Inbound passengers at JFK/UMass would no longer have to play platform roulette, or stand on the overpass and wait for the next train, as all service would take place on a single platform.

|

| Current track layout. |

|

| Proposed track layout showing the combination of the Red Line branches moved further south. |

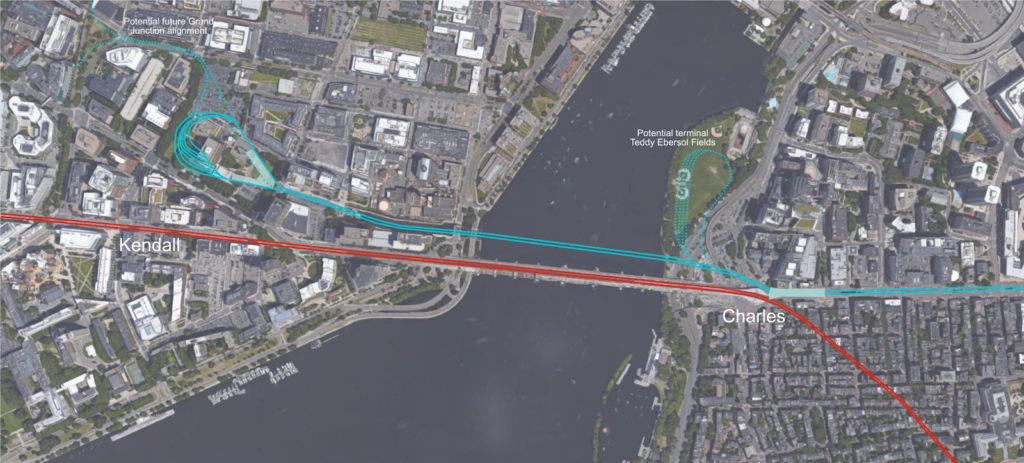

The Cabot Yard leads and Track 61

The tracks from JFK/UMass to Cabot would not have to go unused, however. I pointed out several years ago that Track 61 could reasonably be connected to Andrew Station to provide a shuttle from JFK/UMass to the BCEC and Seaport. With the Cabot yard leads freed up, such a shuttle could instead run from JFK/UMass to the BCEC, providing a connection from Dorchester and the South Shore to the Seaport without relying on the overburdened Silver Line. There should be enough room for two light rail tracks from JFK/UMass to the Seaport (with a single-track terminal at JFK, much like the Braintree branch of the Red Line is being operated after the derailment) with the other Red Line track given over to the Commuter Rail. This would provide a useful link using the otherwise-excess right-of-way.

Cabot Yard as midday layover for Commuter Rail

While Cabot Yard is poorly-located as a Red Line facility, it is in the right place for midday Commuter Rail storage. This page is on the record saying that the best way to reduce the need for midday storage is to just run more trains, but peaks will be peaks, and having somewhere near a terminal to store trains will be important until we build the North South Rail Link (in which case trains will be able to run through the tunnel to outlying yards, freeing up land near the terminals). Today, the Commuter Rail system uses yards at Southampton (near Cabot) and Readville (at the end of the Fairmount Line, so not near Cabot, or really anything) for midday train storage.

Yet to run more trains, the agency needs more storage, so it is looking at sites in Allston and Widett Circle, despite the expense of building in these locations and their desirability as development sites. (As a participant in the planning process for Allston, the supposed need for storage drives many undesirable and expensive portions of that project.) If Cabot Yard was vacated by the Red Line, it would make a fine facility for midday storage: it’s very close to South Station and, with a rail yard on one side and bus yard on the other, a less-desirable development site. The portion of the facility between the Haul Road and 4th Street is more than double the size of Readville, and could thus replace Readville entirely while providing enough additional capacity to obviate the need for new construction in Allston or at Widett Circle.

Conclusion

As usual, actions taken in one location decades in the past cascade through the entire transportation network. NIMBYs in the 1960s pushed the T to build Cabot Yard, even if it was nowhere near the Red Line itself. A changing economy means that the land it occupies, which was little more than a post-industrial wasteland in the 1970s, is now worth hundreds of millions of dollars. The Braintree Split, built in the 1950s, provides enough room for a rail yard in its median. Malfunction—er, Columbia—Junction has always been a solution looking for a problem. By thinking pretty far outside the box, we could correct many of the mistakes of the 1970s. But it involves making an investment in infrastructure beyond just fixing what we have.

The current administration, it seems, is willing to double down on the mistakes which got us in to this mess. When the Muddy River flooded in to the Green Line, we didn’t just build a storm barrier and hope that it would work. We looked upstream for the cause, and rebuilt the Muddy River to keep it from overflowing in the first place. While the reactive solution might seem cheaper today, in the long run, unless we take proactive, decisive action, we’ll pay for the mistakes again and again.