I recently wrote about short turning a bus on the EZRide Shuttle route. People will ask: “why doesn’t the T do this, my bus is always bunched?!” The answer is a) it’s not easy to do, b) they are way too understaffed to do so, and c) their schedules are so much more complex that there are many more moving parts. At rush hours, the T has four dispatchers watching 100 buses; my office has one or two watching nine (although it’s not our only job, sometimes it demands full attention). The need for short turns arises at times when there is heavy traffic and ridership. At those times, it’s all the dispatchers can do at that time to keep some semblance of order among the 250 buses they’re watching, not turn their attention to one particular part of one single route.

And also: there are only so many places and times you can successfully execute a short turn. Our route has a lot of twists and turns which make it easy for a bus to take a right instead of a left and go from outbound to inbound, but often a short turn may require a bus to go around a narrow block in traffic, and you certainly don’t want a bus getting stuck on a narrow corner where it doesn’t belong. There are more issues with the T: we know our drivers are on one route and that their shifts end around the same time. I’ve actually had times where a driver couldn’t cover an extra run because he or she had to be at another job; this is more frequent at the T where shifts start and end in a very complex scheme and at all hours of the day; a driver might finish one trip and set out on a different route, so a short turn would find them far away from where they needed to be. And finally, the T has thousands of drivers, so there is no way for a dispatcher to know whether a driver is familiar with the route and where to make a turn, or whether it’s his first day in the district and he or she is following the route for the first time.

Trains? Buses are much easier than trains. Trains require operators to change ends, change tracks—often at unpowered switches—and obtain a ton of clearance to do so, especially on the older sections of the MBTA system which don’t have the kind of new bi-directional signaling systems that, say, the DC Metro has. If the T had pocket tracks in the right places, it might be easier. But without them short turns would only save time in a few circumstances and a few areas.

And on a train you’re dealing with even more passengers. I’ve been on trains expressed from Newton Highlands to Riverside. Even with half a dozen announcements, a couple of stray passengers won’t pay attention (buried in their phone, perhaps) and then wonder why the train is speeding past Waban. I’ve heard of crews at Brigham Circle, after switch the train from one side to the other, walking through the car rousing passengers who are on another planet (or just staring at their phones). If you can’t run a short turn expediently, it’s not worth doing at all.

That being said, I have a couple of thoughts on routes which could benefit from more active management and, perhaps, some short turns. Both are frequent “key” routes, both experience frequent bunching, and both carry their heaviest loads in the middle of the routes, so that the passengers from a mostly empty bus in the trailing half of a pair could be transferred forwards without overcrowding the first bus. The are (drumroll please): the 1 and the 39. Let’s take a quick look:

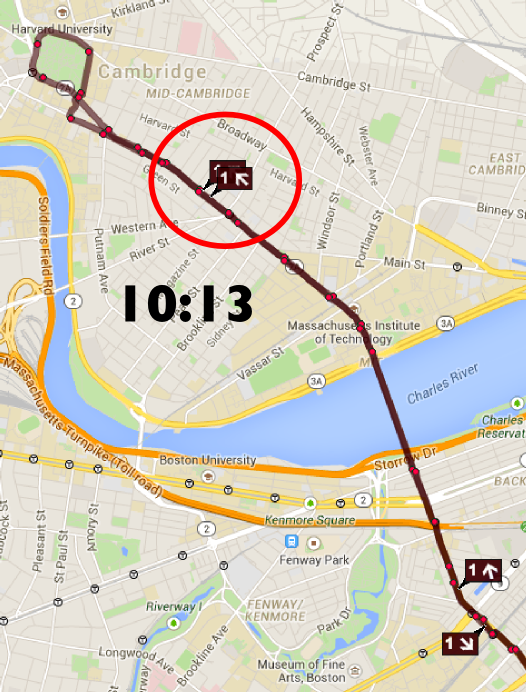

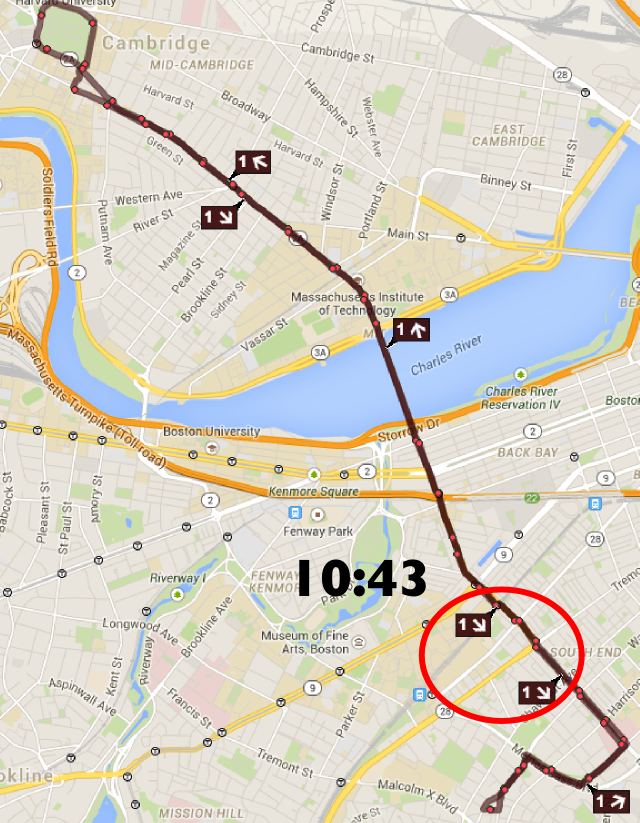

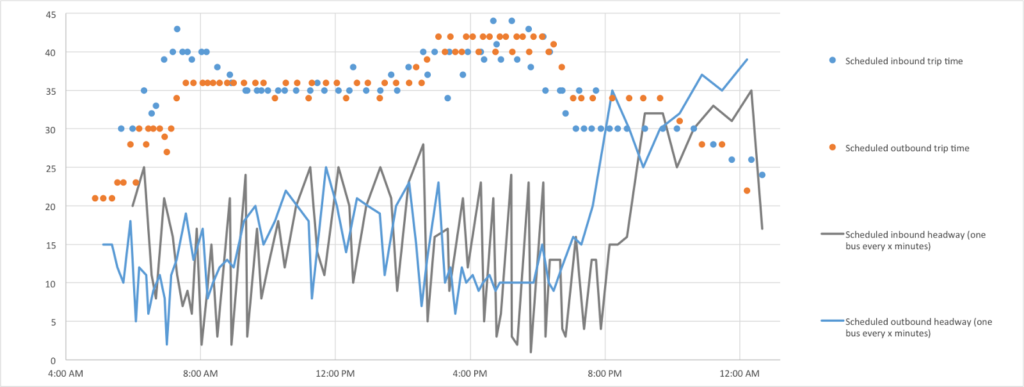

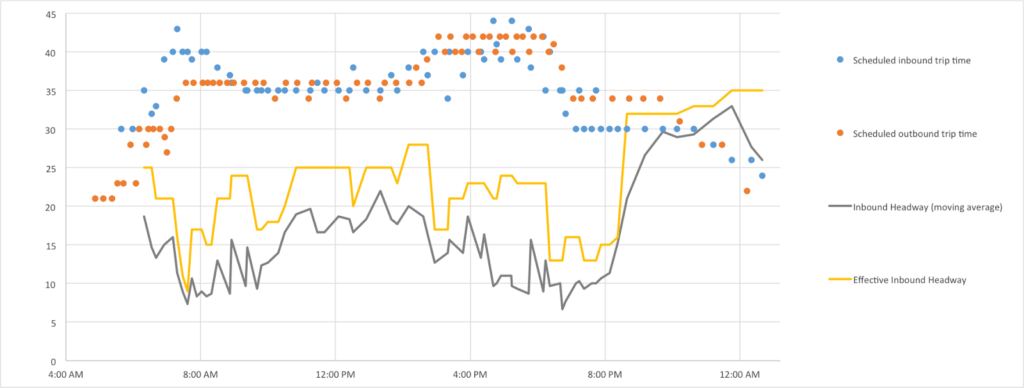

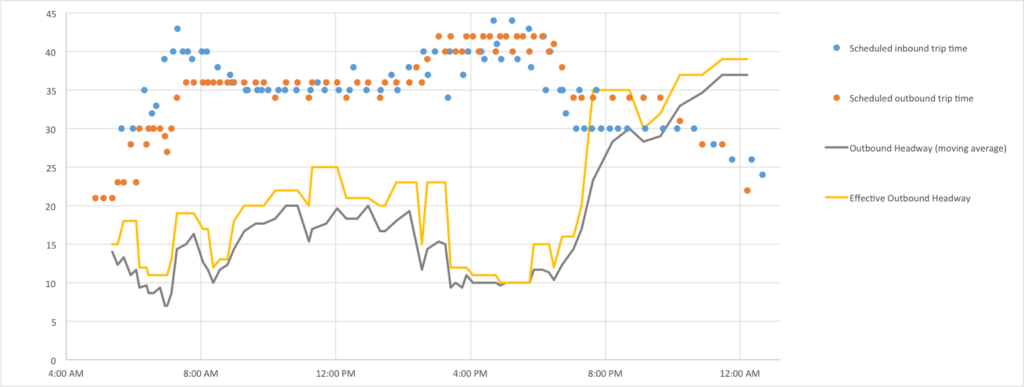

|

| Actual NextBus screen shot for the 1 bus. |

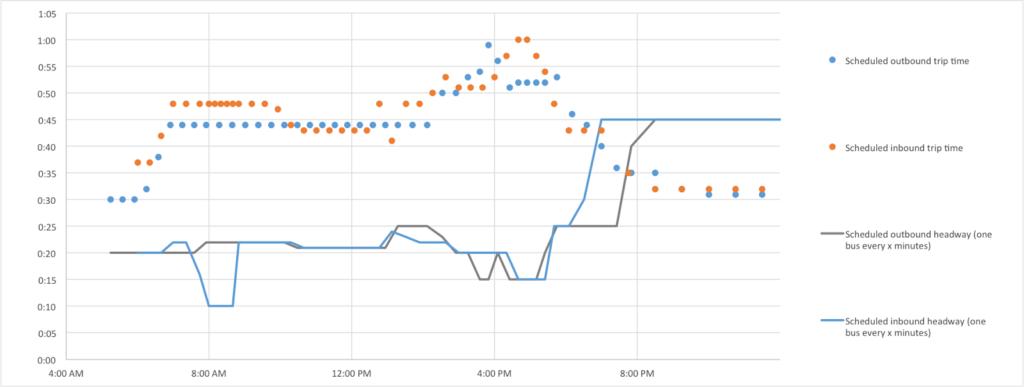

1. The 1 Bus is one of the busiest routes in the system (combined with the CT1, the Mass Ave corridor has more riders than any other such route except the Washington Street Silver Line) and frequent headways of 8 minutes at rush hours. There is no peak direction for the route; it can be full at pretty much any time in any direction. And it is hopelessly impacted by crowding and traffic, such that bunching is almost normal, and on a bad day, three or even four 1 buses can come by in a row, with a subsequent service gap. (It could benefit, you know, from bus lanes and off-board fare collection, but those are beyond the purview of this post.)

But the 1 has a couple of features that make it a candidate for short turning. First of all, its highest ridership is in the middle of the route. The route runs from Dudley to Harvard, but the busiest section is between Boston Medical Center and Central Square. Going outbound (towards Harvard) many passengers get off at Central to transfer to the Red Line or other buses, inbound (towards Dudley), many passengers get off at Huntington Avenue and the Orange Line to make transfers. So here’s a relatively frequent scenario:

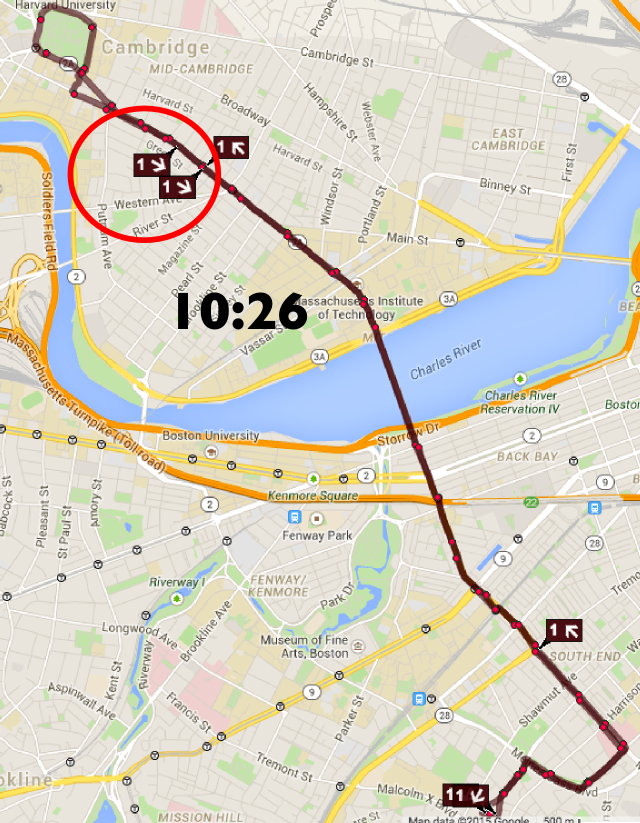

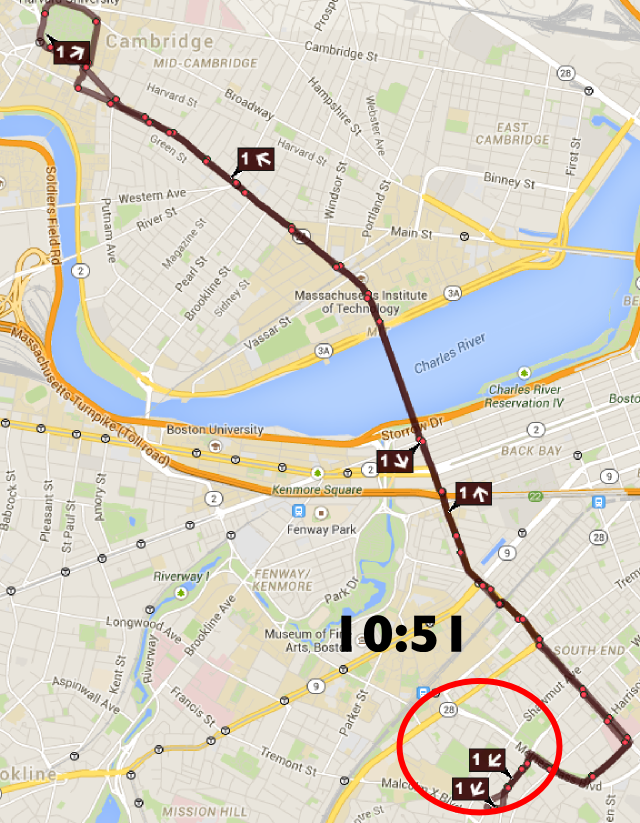

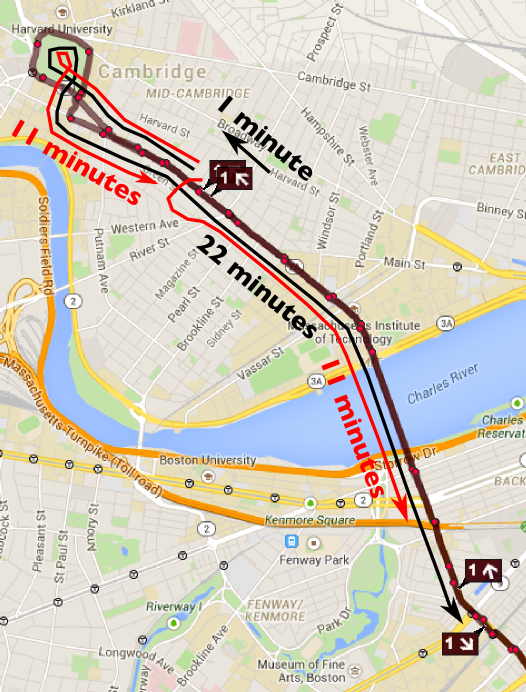

|

| The black lines show the actual headways. The red shows what could be accomplished by short-turning one of the bunched buses at Central Square. |

An outbound 1 bus gets slightly off headway, encounters heavy crowds, is filled up, and runs a few minutes behind schedule. Meanwhile, the bus behind encounters fewer passengers, spends less dwell time at stops, and catches the first bus. The first bus may have 60 passengers on board and the second 30. The buses remain full past MIT and pull in together to the stop at Central Square, where two thirds of the passengers disembark (and few get on: it’s faster to the the Red Line to Harvard or beyond). So now, the first bus has 20 passengers on board, and the second 10. In the mean time, since the first bus is behind schedule, there is now a 20 minute service gap: the first bus should have looped through Harvard by now, and if the buses proceed as a pair, the first bus will pull right through the loop and head out late and with a heavy load, and even if the second bus has a few minutes of recovery, it will quickly catch the first, and the process will repeat inbound.

You won’t be shocked by this, but I went to Nextbus, pulled up the map for the 1 bus, and at 10:15 p.m. on a weeknight, found this exact scenario. See the map to the right. The first bus has gotten bogged down with heavy loads, so there is a 22 minute gap in front of it, while there is another bus right behind. The bus in front should be going inbound at Central right now, but instead both will continue to Harvard, loop around, and start the route bunched: the second bus will lay over for about three minutes and, most likely, after passing several vacant stops, be right on the tail of the first.

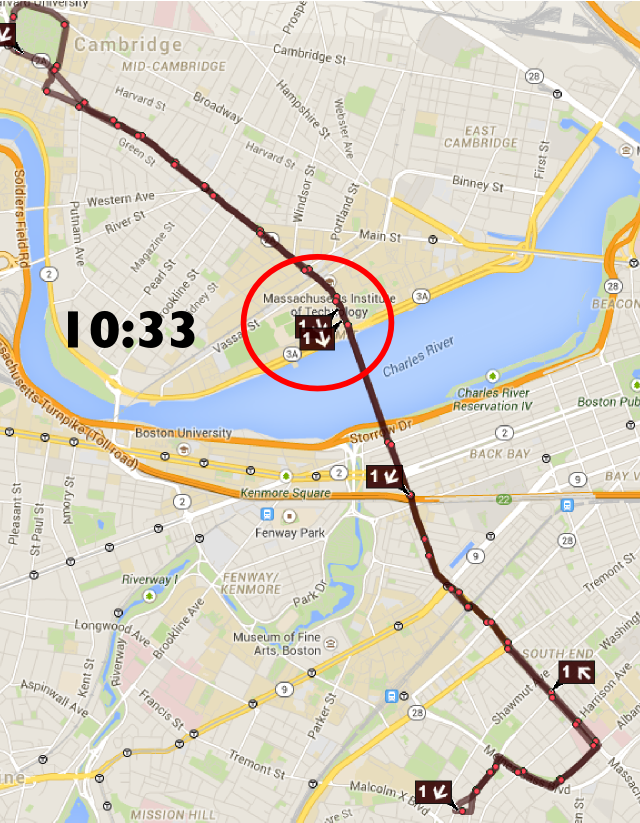

|

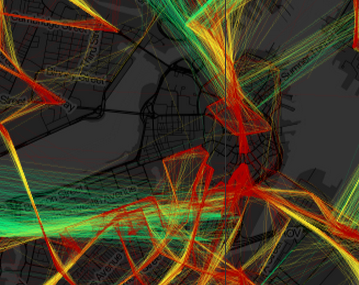

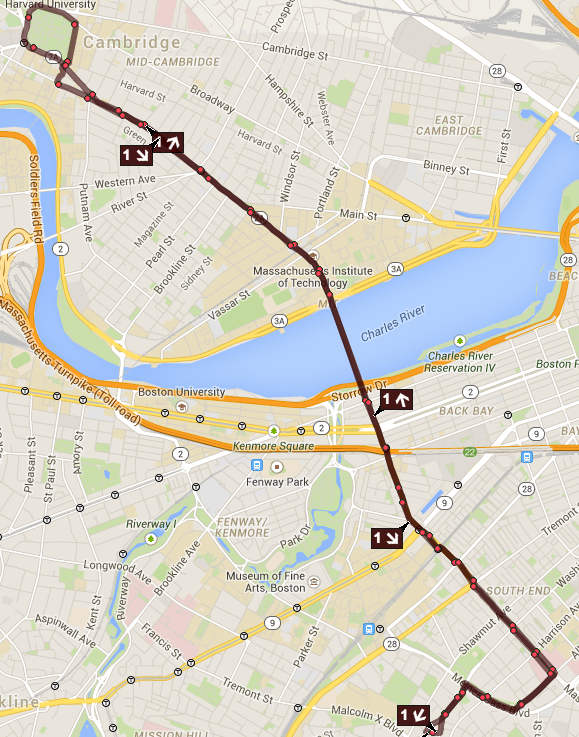

| This is what the 1 bus route should look like without any bunching. This is somewhat rare. |

And the loop is a particular problem since there is not time or space there for the route to have recovery time, so if a pair of buses enters bunched, they are likely to leave bunched as well. Instead of having proper recovery time at each end, only Dudley serves to even out headways. So bunches are much more likely on the inbound (Harvard-Dudley) having occurred going outbound. And given the traffic, passenger volume and number of lights on this route, bus bunching is likely.

But what if, magically, that bus could be going inbound? Well, it could, and it wouldn’t be magic. It would be a short turn. If a dispatcher were paying special attention to the route, the operators could consolidate all passengers on to one bus in Central Square. At this point, the empty bus could loop around and resume the trip inbound from Central (even waiting in the layover area for a minute or two if need be to maintain even headways), where the bulk of the passengers will be waiting. The bus with passengers will continue to Harvard. On the subsequent trip, every passenger’s experience will be improved. Anyone waiting for a bus inbound from Central will have service 10 minutes earlier—on a proper headway. And passengers between Harvard and Central will have a bus show up when it would have, except instead of quickly filling up as it reaches stops which have had no service for 22 minutes and subsequently slowing down, it will operate as scheduled.

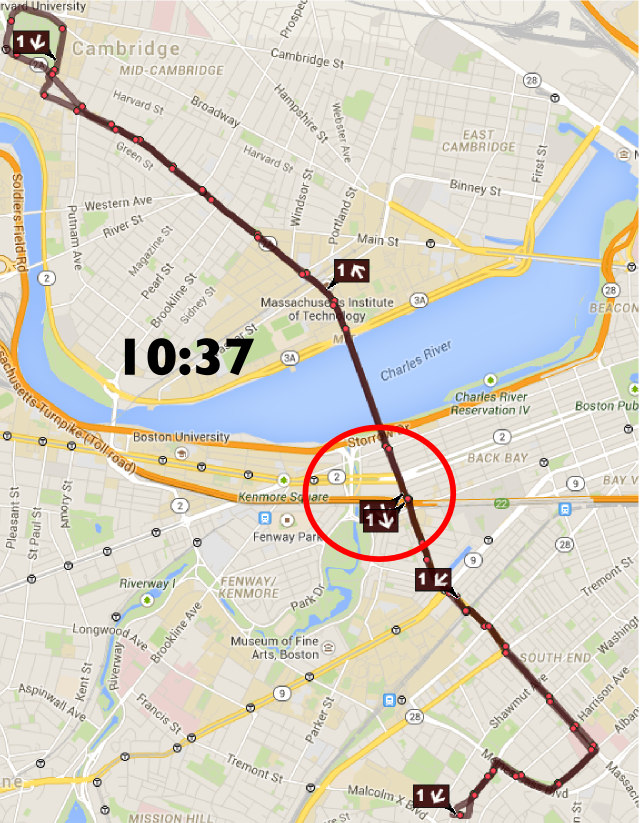

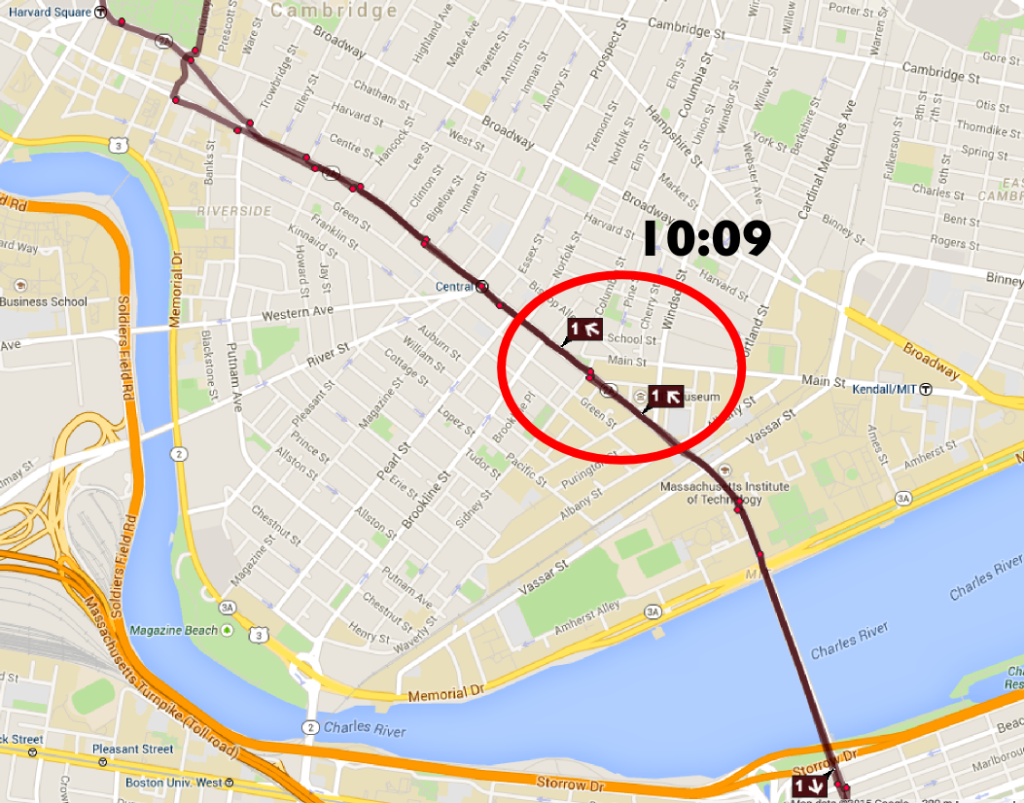

|

| Note that one bus is catching the other. This is the start of the bunch. 10:09 PM. It’s not too late to short turn! |

I watched the route for a while longer, and as predicted, the pair of buses looped through Harvard together, and then traversed the entire inbound route back-to-back, meaning that everyone there waited ten extra minutes, only to have two buses show up together. Every inbound passenger experienced the wonders of a 22 minute headway when the route is scheduled for 12. However, with one dispatch call and a transfer of a few passengers in Central, the headways could have been normalized, and the route could have been kept in order. An issue which was apparent at 10:09 (see the screen capture to the right) could have been fixed at 10:15; instead it lasted until nearly 11:00 (see below):

Now, is this easy? Hell, no, it’s not easy. First of all, the drivers have to know that it might happen. Then, they have to be able to clearly communicate it to the passengers. (If you focused on a couple of routes, you could have Frank Ogelsby, Jr. record some nice announcements. Imagine that deep baritone saying “In order to maintain even schedules, this bus is being taken out of service. Please exit here and board the next bus directly behind.” Oh, and of course, “we apologize for any inconvenience this may have caused.”) You’d have to be damn sure that there was another bus behind and its driver was instructed to pick up the waiting passengers. And a thank you Tweet (@MBTA: Thank you to the passengers of the 1 bus who switched buses so we could fill a service gap at Central) would be in order.

Would it be perfect? No. Sometimes you’d have an issue with a passenger who didn’t want to get kicked off the bus. If a bus had a disabled passenger on board, the driver could veto the short turn based on that fact, since the time and effort to raise and lower the lifts would eat in to the time saved by the turn. But most of the time, if executed well, the short turn would save time, money, and create better service for most every rider.

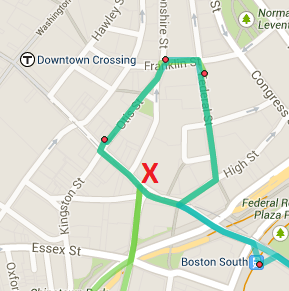

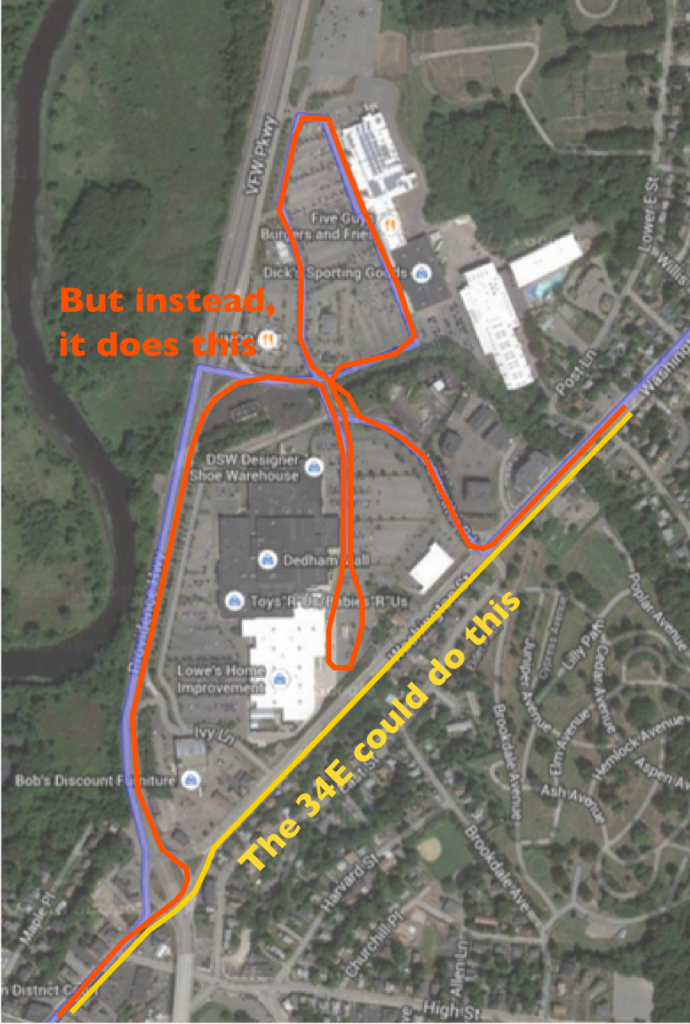

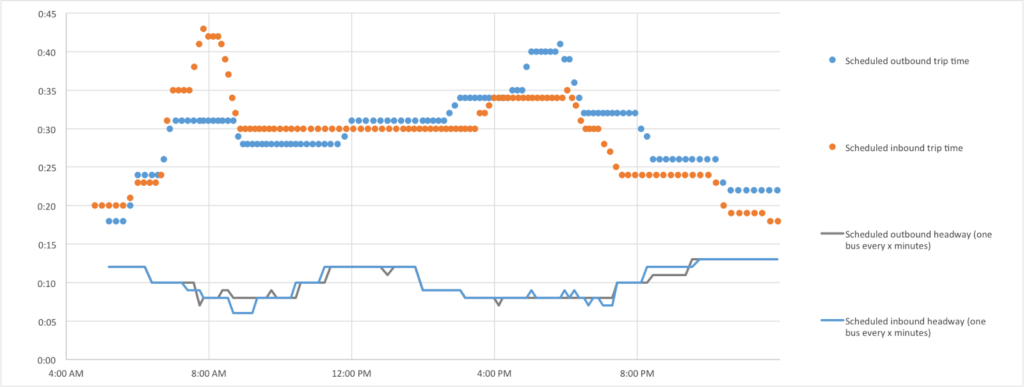

39. The 39 bus is similar. It is heavily used, and it bunches frequently. It also has its heaviest loads in the middle: the stretch between Back Bay Station and Copley is mostly a deadhead move, the bus only really fills up in the Longwood area, and the bus is mostly of empty of passengers along South Street from the Monument in JP to Forest Hills. So at either of these locations, a similar procedure could take place. If two buses were bunched going inbound, the first could drop off in Copley, take a right on to Clarendon, a right on to Saint James and begin the outbound route, rather than looping in to Back Bay and then out again to backtrack to Berkeley before beginning the route. Back Bay is necessary as a layover location when buses are on schedule, but there’s no reason to have a bus go through a convoluted loop when it could be short turned and fill a gap in service.

At the other end, two bunched buses could consolidate passengers on Centre Street in Jamaica Plain, at which point one could loop around the Monument (already the layover point for the 41) and begin a trip inbound, while the other would serve the rest of the route to Forest Hills.

So those are my two bus routes that could be short-turned and unbunched. Combined, they carry 28,000 passengers per day: the busiest routes in the system. I would propose a pilot study where the T figured out when these routes are most frequently bunched (they have these data) and then assign a dispatcher to watch only these two routes during these times and, when necessary, short-turn a bus to maintain headways, along with some driver training to ensure proper customer service and expedient routing. It could also record messages, put up some signs, and make sure to have some positive outreach to passengers. This could be done for a period of time, and the results analyzed to see the effect of actively dispatching such routes. If it were deemed a success—if there were fewer bunches and service gaps (data could show this)—the program could be expanded, and perhaps automated: any time buses were detected as being bunched, a dispatcher could be notified, and then make a decision on whether it would be appropriate to short-turn the bus, or not.

The passengers—well, we’d certainly appreciate it, too.