The MBTA’s Fiscal and Management Control Board, according to their slides, wants to “think big.”

Thinking big is a laudable goal. The only problem is that big thinking requires feasibility, and it is a waste of everyone’s time and energy if the big thinking is completely outside the realm of what can reasonably occur or be built.

Thinking big is a laudable goal. The only problem is that big thinking requires feasibility, and it is a waste of everyone’s time and energy if the big thinking is completely outside the realm of what can reasonably occur or be built.

Case in point: combining Park Street and Downtown Crossing into one “superstation.” The first reason this won’t happen is that it doesn’t need to happen: with the concourse above the Red Line between the two stations, they are already one complex. (#Protip: it’s faster to transfer between the Red Line at Park and the Winter Street platform on the Orange Line—trains towards Forest Hills for the less anachronistic among us—by walking swiftly down the concourse rather than getting on the train at Downtown Crossing.) But there are several other reasons why this is just not possible.

Tangent track

To build a new station between Park Street and Downtown Crossing would require tangent, or straight, track. If you stand at Park, however, you can’t see Downtown Crossing, because the tracks, which are separated for the center platform at Park, curve back together for the side platforms at Downtown Crossing. This curve is likely too severe to provide level boarding, so the track would have to be realigned through this segment. So even if it were easy to build a new complex here, the tracks would have to somehow be rebuilt without disrupting normal service. That’s not easy.

Winter Street is narrow. Really narrow.

The next, and related, point: Winter Street is very narrow: only about 35 feet between buildings. Park Street Station is located under the Common, and the Red Line station at Downtown Crossing is located under a much wider portion of Summer Street: those locations have room for platforms. Winter Street does not. Two Red Line tracks require about 24 feet of real estate: this would leave 5.5 feet for platforms on either side before accounting for any vertical circulation, utilities and the like. Any more than that and you’re digging underneath the century-old buildings which give the area its character. That’s not about to happen. And Winter Street would be the only logical location for the station; otherwise it would force long walks for transferring passengers.

|

Summer Street (foreground) is wide.

Winter Street (background) is narrow.

The fact that so many streets change names crossing Washington?

Well, that’s just confusing. |

Note the photograph to the right. The current Downtown Crossing station is located between Jordan Marsh on the left and Filene’s on the right (for newer arrivals: the Macy’s and the Millenium building), where Summer Street is about 60 feet wide, enough for two tracks and platforms, and it’s still constrained, with entrances in the Filene’s and Jordan Marsh buildings. Note in the background how much narrower Winter Street is. This isn’t an optical illusion: it’s only half as wide. The only feasible location for such a superstation would be between the Orange and Green lines, but the street there is far too narrow.

Passenger operations

The idea behind combining Downtown Crossing and Park Street is that it would simplify signaling and allow better throughput on the line operationally. But any savings from operations would likely be eaten by increased dwell times at these stations. At most stations, the T operations are abysmal regarding dwell times; Chicago L trains, for example, rarely spend as much time in stations as MBTA trains do, as the operator will engage the door close button as soon as the doors open. At Park and Downtown Crossing, however, this is not the case. Long dwell times there occur because of the crowding: at each station, hundreds of passengers have to exit the train, often onto a platform with as many waiting to board. This is rather unique to the T, and the Red Line in particular, which, between South Station and Kendall, is at capacity in both directions. Trying to unload and then load nearly an entire train worth of passengers at one station, even with more wider doors on new cars, just doesn’t make sense.

If Park and Downtown Crossing were little-used stations, it would make no sense to have two platforms 500 feet apart, and combining them, or just closing one, would be sensible. (Unlike New York and Chicago, the Boston Elevated Railway never built stations so close that consolidation was necessary.) But they are two of the busiest stations in the MBTA system, both for boardings and for transfers. Given the geometry of the area, both above and below ground, calling this a big idea is risible. Big ideas have to, at least, be somewhere in the realm of reality. Without a 1960s-style wholesale demolition of half of Downtown Boston, this is a distraction. The FMCB has a lot to do: they should not spend time chasing unicorns.

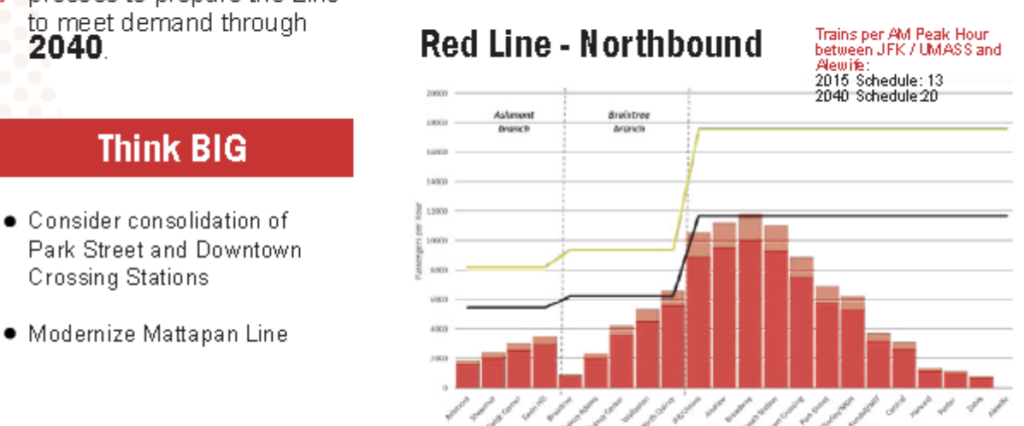

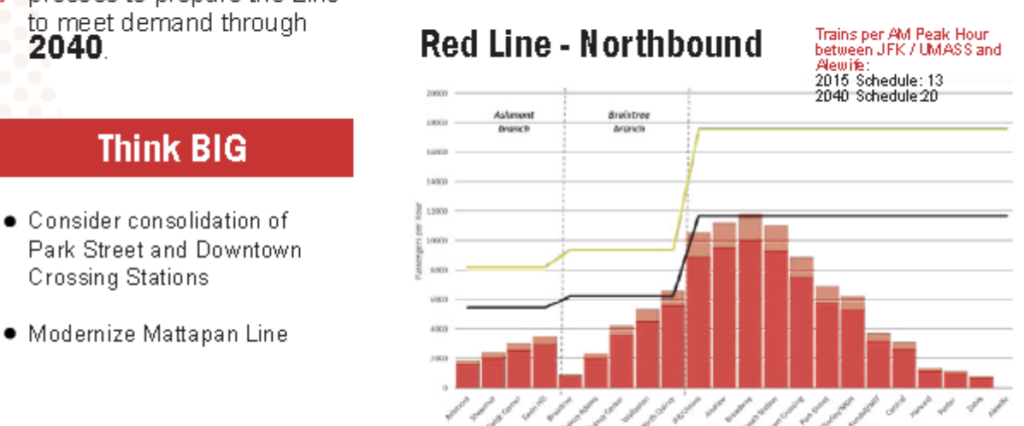

Better Headways? Geometry gets in the way, not just signals.

In addition to a spending time on infeasible ideas like combining Park and Downtown Crossing, the FMCB and T operations claims that it would only take a minor signal upgrade (well, okay, any signal upgrade wouldn’t be minor) to allow three minute headways on the Red Line. Right now, trains come every 4 to 4.5 minutes at rush hour (8 to 9 minutes each from Braintree and Ashmont); so this would be a 50% increase. Three minute headways are certainly a good idea, but the Red Line especially has several bottlenecks which would have to be significantly upgraded before headways can progress much below their current levels. New signals would certainly help operations, but they are not the current rate limiting factor for throughput on the line.

There are four site-specific major bottlenecks on the line beyond signaling: the interlocking north of JFK-UMass (a.k.a. Malfunction Junction), the Park-Downtown Crossing complex, the Harvard curve, and the Alewife terminal. (In addition, the line’s profile, which has a bi-directional peak along its busiest portion, results in long dwell times at many stations.) Each of these is it’s own flavor of bottleneck, and it may be informative to look at them as examples of how retrofitting a century-old railroad is easier said than done. This is not to say that a new signaling system shouldn’t be installed: it absolutely should! It just won’t allow for three minute headways without several other projects as well. From south to north:

JFK-UMass

This is likely the easiest of the bottlenecks to fix: it’s simply an interlocking which needs to be replaced. While the moniker Malfunction Junction may not be entirely deserved (the Red Line manages to break down for many other reasons), it is an inefficient network of special track work which dates to the early 1970s and could certainly use an upgrade. In fact, it probably would be replaced, or significantly improved, with the installation of a new signal system.

Park/Downtown

Right now, Park and Downtown Crossing cause delays because of both signaling and passenger loads. For instance, a train exchanging passengers at Downtown Crossing causes restricted signals back to Charles, so that it is not possible for trains to load and unload passengers simultaneously at Park and Downtown Crossing. Given the passenger loads at these stations and long dwell times at busy times of day, it takes three or four minutes for a train to traverse the segment between the tunnel portal at Charles and the departure from Downtown Crossing, which is the current rate-limiting factor for the line. If you ever watch trains on the Longfellow from above (and my new office allows for that, so, yeah, I’m real productive at work), you can watch the signal system in action: trains are frequently bogged down on the bridge by signals at Park.

A new signal system with shorter blocks or, more likely, moving blocks would solve some of this problem. A good moving block system would have to allow three trains to simultaneously stop at Park, Downtown Crossing and South Station. So this would be solved, right? Well, not exactly. Dwell times are still long at all three of these stations: as they are among the most heavily-used in the system. Delivering reliable three-minute headways would help with capacity, but longer headways would lead to cascading delays if trains were overcrowded. There’s not much margin for error when trains are this close together. Given the narrow, crowded stairs and platforms at Park and Downtown crossing, the limiting factor here is probably passenger flow: it might be hard to clear everyone from the platforms in the time between dwells. And it is not cheap to try to widen platforms and egress. A new signaling system would help, but this still may be a factor in delivering three minute headways.

The Harvard Curve and dwell times

Moving north, the situation doesn’t get any easier to remedy. When the Red Line was extended past Harvard, the President and Fellows of Harvard College would not allow the T to tunnel under the Yard, so the T was forced to stay in the alignment of Mass Ave. This required the curve just south of the station, which is limited (and will always be limited) to 10 miles per hour. The curve itself is about 400 feet long, but if any portion of the train (also about 400 feet long) is in the curve, it is required to remain at this restricted speed. So the train has to operate for 800 feet at 10 mph, which takes about 55 seconds to operate this segment alone. Given that with Harvard’s crowds, it has longer dwell times due to passenger flow, traversing the 800 feet of track within the station and tunnel beyond takes more than two minutes under the best of circumstances.

Would signaling help? Maybe somewhat, but not much. Even a moving block signal system would not likely allow a train to occupy the Harvard Platform with another train still in the curve. Chicago has 25 mph curves on the Blue Line approaching Clark/Lake and operates three minute headways, but they also frequently bypass signals to pull trains within feet of each other to stage them, something the T would likely be reticent to do. It may be possible to operate these headways but with basically zero margin for error. Any delay, even small issues beyond the control of the agency, would quickly cascade, eating up any gains made from running trains more frequently. This is a question of geometry more than anything else: if trains could arrive and leave Harvard at speed, it wouldn’t be an issue. But combining the dwell time and the curve, nearly the entire headway is used up just getting through the station.

Alewife

The three issues above? They pale in comparison to Alewife. Why? Because Alewife was never designed to be a terminal station. (Thanks, Arlington.) The original plan was to extend the Red Line to 128, with a later plan to bring it to Arlington Heights. But these plans were opposed by the good people of Arlington, and the terminal wound up at Alewife. The issues is that the crossover, which allows trains to switch tracks at the end of the line, didn’t. It wound up north of Russell Field, along a short portion of tangent track between the Fitchburg Cutoff right-of-way and the Alewife station, and about 900 feet from the end of the platform. If a train uses the northbound platform, it can run in to the station at track speed (25 mph, taking 50 seconds), unload and load at the platform, and allow operators to change ends (with drop back crews, this can take 60 seconds), and then pull out 900 feet (25 mph, taking 30 seconds) and run through the crossover at 10 mph (45 seconds). That cycle takes 185 seconds, or just about three minutes, of which about a minute is spent traversing the extra distance in and out of the station. If the train is crossing over from one track to the other would foul the interlocking, causing approaching trains to back up. And since this is at the end of the line, there’s significant variability to headways coming in to the station, so trains are frequently delayed between Alewife and Davis waiting for tracks to clear.

Without going in to too much detail, the MBTA currently has a minimum target of about 4 minute headways coming out of Alewife. Without rebuilding the interlocking—and there’s nowhere to do this, because it’s the only tangent portion of track, and interlockings basically have to be built on tangent track—there’s no way to get to three minute headways. In addition, the T is in the enviable position of having strong bidirectional ridership on the Red Line. In many cities, ridership is unbalanced: Chicago, for example, runs three minute headways on their Red Line from Howard at peak, but six minutes in the opposite direction from 95th (this results in a lot of “deadheading” where operators are paid to ride back on trains to get back to where they came from). The T needs as many trains as it can run in both directions, so it has to turn everything at Alewife (never mind the fact that there’s no yard beyond; we’ll get to that). This also means that T has to run better-than-5-minute headways until 10 a.m. and 8 p.m. to accommodate both directions of ridership. While this means short wait times for customers, it incurs extra operational costs, since these trains provide more service than capacity likely requires and, for instance, we don’t need a train leaving Alewife every four minutes at 9:30, except we have to put the trains somewhere back south.

In the long run, to add service, Alewife is probably unworkable. But there is a solution, I think. The tail tracks extend out under Route 2 and to Thorndike Field in Arlington. The field itself is almost exactly the size of Codman Yard in Dorchester. Assuming there aren’t any major utilities, the field could be dug up, an underground yard could be built with a new three-track, two-platform station adjacent to the field (providing better access for the many pedestrians who walk from Arlington, with Alewife still serving as the bus transfer and park-and-ride), a run-through loop track, and a storage yard. I have a very rough sketch of this in Google Maps here.

Assuming you could appease local population and 4(f) park regulations, the main issue is that field itself is quite low in elevation—any facility would be below sea level and certainly below the water table. But if this could be mitigated, it would be perhaps the only feasible way to add a yard to the north end of the Red Line. And it is possible that a yard in Arlington, coupled with some expansion of Codman (which has room for several more tracks) could eliminate the need for the yard facility at Cabot Yard in Boston, which is a long deadhead move from JFK/UMass station. While the shops would still be needed the yard, which sits on six acres of real estate a ten minute walk on Dot Ave from Broadway and South Station, could fetch a premium on the current real estate market.

This wouldn’t be free, and would take some convincing for those same folks in Arlington, but operationally, it would certainly make the Red Line easier to run. Upgrades to signals and equipment will help, but if you don’t fix Alewife, you have no chance of running more trains.

Overall, I’m not trying to be negative here, I’m just trying to ground ideas in realism. It’s fun to think of ways to improve the transit system, but far too often it seems that both advocates and agencies go too far down the road looking in to ideas which have no chance of actually happening. We have an old system with good bones, but those bones are sometimes crooked. When we come up with new ideas for transit and mobility, we need to take a step back and make sure they’ll work before we go too much further.

Today’s glossary:

- Deadhead: running out of service without passengers. All the cost of running a train (or, if an operator is riding an in-service train, all the costs of paying them), none of the benefits.

- Headway: the time between train arrivals

- Tangent track: straight track

Editor’s note: after a busy first half of the semester, I have some more time on my hands and should be posting more than once every two months!