Gas prices are low.

Really, really low.

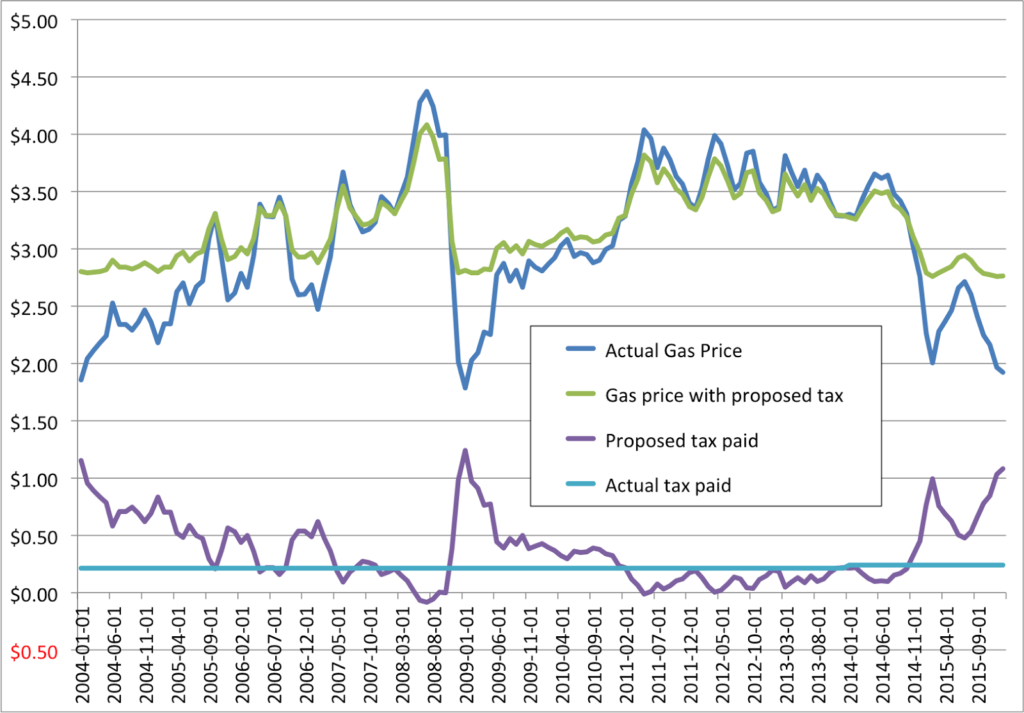

But gas prices are also volatile. They can swing—and have swung—by 200% in a few months. What other such omnipresent commodity has such wild price swings? Eggs? Maybe. Gas prices were low in the early 2000s, rose mid-decade and then spiked after Katrina, rose further in 2008 to more than $4 per gallon, plummeted with the economy and bottomed out below $2 in 2009, rose back to $4 by 2011 and have since dropped back under $2.

This is all related to the base cost of oil, variable global demand and long lead times for production. But one thing that doesn’t change with gas prices are gas taxes. If gas is cheap, the tax is the same per gallon. Expensive? Same tax. There’s a pretty good reason that gas is not taxed as a percentage: it would be punitive when prices were high (which can be harmful to the economy) and wouldn’t raise enough money when prices are low. So we have a set tax per gallon.

But it’s not enough. In Massachusetts, the economy is doing well, but is held back by pesky infrastructure. We can’t rest on our laurels, but we seem unwilling to pay for what we need.

The problem is that—especially given the recent volatility in prices—raising the gas tax makes people worry, somewhat rightfully, that the tax will cause high gas prices to go even higher. Sure, gas might only be $1.79 today, but if there were another oil crisis and gas spiked to $4.25, would we really want to tack on another ten or fifteen cents? There’s a very cogent response that, no, we would not: gasoline usage is very inelastic as most travel is non-discretionary. Sure, some people will switch to other modes, and some won’t make trips, but higher gas prices mean that middle-class consumers have less money to spend on other goods. Raising the gas tax when the price is high is akin to hitting consumers while they’re down.

But low prices are just as perverse, for the external effects of gasoline usage. Low gas prices provide little incentive to purchase fuel efficient vehicles, so more consumers buy gas guzzling vehicles, which lead to more pollution, climate change issues, and boneheaded government programs when gas prices rise and everyone cries poor. Gas price volatility is a problem for pretty much everyone.

The gas tax is really different from every other tax. Few other taxes are on a good with a price as volatile as gasoline. Other taxes which we use, in theory, to reduce the consumption of a good (“sin taxes” on cigarettes, for example) can stay high even if prices rise, since there is no economic benefit to easy access to them. Many other taxes are collected as a percentage, but that is anathema for gas taxes as it would only serve to exaggerate price changes. What we really need is a tax that is high when gas prices are low, and low when gas prices are high.

Paul Krugman has cogently argued for a price floor for gas, but this has a couple of issues. It completely disrupts the supply and demand curves with a flat floor, so there is no natural variability in the gasoline markets. Second, if the price of gas rises above the “floor”, gas tax revenues cease; it it rises high enough, a major funding source for transportation dries up. (But, I must point out, one that does not come close to covering the full cost of our roadways; in fact, roadways in most states, including Massachusetts, have a “gas tax recovery” ratio of about 40%, similar to the MBTA’s farebox recovery, so subsidies are about the same.)

Another issue with a floor is that with volatile gas prices, it would mean that the floor price and the actual price would often be quite disparate, and it would have to be implemented on a national scale to keep motorists from having a high incentive to cross state lines. There’s no incentive built in, so it’s harder to sell as having any benefit when prices are high. It also requires all gas stations to charge the same price even though non-gas expenses—real estate, operations—often result in prices which differ by area and business. It’s a blunt instrument.

But what if you split the difference and had a gas tax which rose and fell inversely to the price of gas. When gas is cheap, the tax would be high, providing a sort of moving floor. When gas prices spike, some of the tax revenues could be saved and actually help to mute some of the spike with a rebate: so if the base price of a gallon of gas climbed to $4.50, consumers might only pay $4. I would contend that there is not much difference between gas prices of $1.75 and $2.50—both are considered cheap. Cheap gas is bad, and expensive gas is bad, and volatility is worse. With this sort of plan, when gas prices are low—which often correlate to a more sluggish economy—you get extra money for infrastructure improvements which provide jobs and economic stimulus. When they are high, the effect of the high price is muted somewhat, dampening the effect on the economy of high prices.

Let me put it another way. In the 2015, gas prices ranged from $1.97 to $2.71. Was gas expensive in the last year? No, it was cheap. What if there had been a tax which meant that prices ranged from $2.66 to $2.98? Would gas have been expensive? No, because under-$3 gas is still cheaper than any time since 2011. $3 gas doesn’t kill the economy. $5 might.

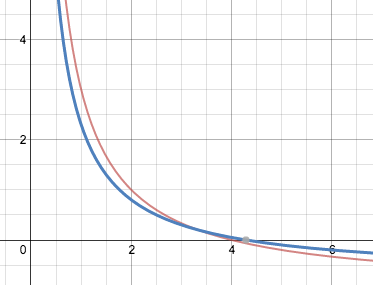

Looking back at the last twelve years of gas price data, I’ve come up with an idea which would raise the average gas tax—thus raising revenues for road and transit projects—but would also reduce the volatility of gas prices and, when prices are very high, actually reduce prices at the pump. Note that this is in relation to the Massachusetts state tax of 24¢, but would be just as applicable to the federal 18.4¢ per gallon tax. If the price of gas per gallon is G, then the tax would be:

4/G-$1

Note that these numbers can be moved around to increase or decrease the taxes paid, or to change the variability of the tax. For instance, $3/G-$0.70 would yield a tax with more variability; a lower floor but fewer savings when prices are high. But this seems to be a happy medium which matches the experience of the past 12 years well.

As for the costs—going off a baseline of the before-state tax price of gas (take the current price at the pump and subtract 24¢ in Massachusetts):

At $2, this would yield a tax of $1 per gallon and a price of $3

At $3, the tax would be 33¢ per gallon, for a price of $3.33

At $4, the tax would be 0¢ per gallon—a savings of 24¢ per gallon compared to the current tax rate—and the price would be just $4.00

At $5, the tax would be -20¢ per gallon, meaning that the price would be a quarter lower than it otherwise would have been; the price would be $4.80

If gas prices were to drop to $1—and this is unlikely, as it would equate to basically free oil—the system would break down a bit, as the tax would be $3.00 and the price $4.00, so some baseline could be built in (maybe a maximum tax of $1.25). If gas were to spike to $6, the tax would fall to -33¢, so the rainy day fund would be able to pay in to that for a while before becoming exhausted (and the tax could have a provision to readjust when a certain portion of the rainy day fund was paid out).

Had this sort of tax been in place since 2004, prices would have ranged from $2.76 to $4.01 over that time, rather than the actual range from $1.82 to $4.38. (The 3G-$0.70 would yield a slightly larger range of $2.55 to $4.15.) It would mean a goodbye to very, very cheap gas. But we seem to have survived somewhat higher prices. We even celebrated when gas prices dropped below $3 for “the first time in, like, forever” back in the heady days of—let me check the dateline—October 2014. Having gas prices stay in the $2.50 range, even when the price of a barrel of oil plummets, is not necessarily a bad thing.

There would be plenty of benefits. One would be predictability for auto purchasers. Cars are durable goods, and a single vehicle can last through several oil price cycles. Consumers buying less-efficient cars would have a better idea of what gas prices would be, and they would no longer drop so low that inefficient cars would become (relatively) cheap to operate. And when prices spiked, it would be less of an impact for these consumers. High efficiency buyers would be incentivized to buy cars without the worry that recouping the extra cost for a hybrid or alternate fuel vehicle would be negated by a drop in prices. It would even benefit automakers, who would be able to better plan vehicle models and production schedules knowing that the volatility of gas prices would have less of an effect on consumer choice.

While this tax could be implemented as a revenue-neutral scheme, it would also make a revenue-positive gas tax more palatable. For instance, the tax described above would have averaged 37¢ from 2004 to 2015, during which time the gas tax in the Commonwealth was 21.5¢ (21¢ for 10 years, 22¢ for two). The gas tax in Massachusetts raises about 38 million dollars for every penny it goes up (and an average increase of 10¢—just 5% of the volatility in prices in the past decade—would be very unlikely to bend the demand curve significantly) so raising the tax from 21.5¢ to 37¢ would have raised a net of $7 billion dollars. That includes money for the rebate drivers would have received in 2008, when the tax would have been -9¢. That certainly would have been beneficial to the economy, which was already teetering on the brink for a variety of reasons, and certainly wasn’t helped by $4.50 gas.

There are some issues to this scheme, but they would be surmountable. First is that if the price of gas was consistently high, the tax—and the necessary revenue—would disappear. So any such tax would need a set amount that the rainy day fund would pay out and a specific criteria to recalibrate the tax towards a new baseline. If there were a few years of cheap gas, a months-long spike wouldn’t be an issue. If gas prices spiked for a long time, the tax would have to rise, but could keep the same adjustability provisions. (Why not set it to inflation? There are two issues. The first is that gas and inflation correlate very little. The second is that gas prices are part of the inflation, so if gas prices go up, inflation goes up, and this, if anything, causes a feedback loop.)

Another issue is that if prices are a lot higher in one state than in another, people are going to cross borders to buy cheaper gas. This would be an issue, but not a huge one. There are already disparities in gas taxes between states, although Massachuetts’ population is generally concentrated away from borders, and the distance that it’s worth traveling to save money on gas is relatively small. People are also more likely to feel the pinch of prices and try to avoid them when overall prices are high, and when prices are relatively high—above $3—the price disparity would be relatively small. And when gas prices are high, this gives the state an economic advantage, as residents would have more disposable income for other purchases. (You could even allow some gas stations very near the border to opt out of some of the increase in the tax when the prices were low, but they’d also have to give up the tax rebates when prices were high.)

Why not use a Vehicle Miles Traveled tax, or a VMT? There are variety of reasons. First of all, a VMT does not have the benefit of encouraging people who do need to drive to drive smaller cars, which this would. Second, it would be harder to sell a VMT than a gas tax, as there is a vocal minority of citizens very worried about the government tracking their movements (note to the tin foil hat crowd: that ship sailed a long time ago). The gas tax works. The main issue is that since it is so rarely raised, it has lost the purchasing power it needs

The idea of this plan is to pair a gas tax increase with the sweetener that, when the gas tax is most perverse and regressive, the pain would be muted. This has the potential to appeal to a wider portion of the population, because everyone remembers high gas prices, and it would actually help to reduce those spikes. We certainly need to increase transportation funding. The gas tax is a good tool, but we need to think outside the box and figure out how to make it work better, no matter the price of gas.

Would this work politically? There’s no way to know. But it would diffuse the argument that if we raise gas taxes and then prices go up, it hits low- and middle-income families hardest. This would actually give a tax break to motorists at times of high taxes. Maybe that would be a rallying point and a compromise to get the funding that we need while reducing the adverse impacts of the volatility of gas prices.