When a teenager borrows his parent’s car for a cruise around town, he assumes that driving is cheap. He drives 20 miles, put a dollar’s worth of gas in the tank, and voila, it only costs 5¢ per mile. Never mind that mom and dad plunked down $20,000 for the car, paid sales and excise taxes, and take it in for maintenance (and probably pay for the increased insurance cost that come from having an inexperienced driver as well). Those are all fixed costs, whether Junior drives it or not. Junior only pays the marginal cost of driving—a few cents per mile—which is a small percent of the actual cost of owning and operating a car, so to him, it seems pretty cheap.

The Frontier Institute makes exactly this point in a recent blog post (I even get a mention!). Now lets extend this logic to the recent, inaccurate report that the CapeFlyer train makes a “profit”, while weekend Commuter Rail service operates at such a loss that the MBTA Fiscal Control Board wants to cut it. The Control Board unfairly compares the two services, using the same “logic” that makes Junior think that driving is a great bargain.

If someone else pays for every aspect of driving except for the gas, then, yes, driving seems cheap. If someone else pays for the all of the fixed costs of operating a passenger rail service except for the crew and the fuel—as is the case with CapeFlyer—it seems cheap as well. Comparing CapeFlyer’s marginal costs against the overall cost of Commuter Rail is as silly as saying that a teenager’s topping up the tank of their parents’ car pays the entire cost of car ownership.Yet that’s exactly what the MBTA Control Board does in claiming that the “innovative” CapeFlyer is a model for weekend Commuter Rail funding. It’s not.

A bit of background: in 2013 MassDOT and the MBTA started running the long-overdue CapeFlyer service from Boston to Hyannis (in about 2:20, just 35 minutes slower than 1952!). The train makes three round trips per week, one each on Friday, Saturday and Sunday, from Memorial Day to Labor Day. It has decent ridership—nearly 1000 per weekend—which is not bad given its limited schedule. And according to every published report, it turns a profit.

Wait, what? A train turns a profit three years in a row? If it’s that easy to turn a profit, then we should have Commuter Rail popping up all over the place, right? Private companies should be clamoring to run trains every which way. If it is profitable to run a few round trips a week to the Cape (with mostly-empty trains back; I can’t imagine there are a lot of Cape Codders coming back to Boston on a Friday evening), then surely full rush hour trains—some carrying upwards of 1000 passengers—must make a mint for the MBTA.

Of course, the reason the CapeFlyer makes a profit is because its finances are accounted for very differently than the rest of the MBTA: it makes a profit against its marginal operating costs, but this misleading calculation does not account for the significant fixed costs that come from running a railroad. There’s nothing wrong with this – the CapeFlyer runs on the weekend and uses equipment, crews and trackage which would otherwise sit idle. It’s a good idea to offer people more rail options. That’s not the issue.

The issue is that when the MBTA Control Board proposes cutting Commuter Rail weekend service, they compare that service against the CapeFlyer, without accounting for the fixed costs that CapeFlyer doesn’t have to worry about. If we analyze the cost of weekend Commuter Rail service the same way we analyze the cost of CapeFlyer service, the Commuter Rail service would look a whole lot cheaper than the T’s Control Board makes it out to be. But when the preconceived agenda is to cut service, a fair comparison quickly becomes an inconvenient comparison, and therefore they resort to the accounting equivalent of comparing apples with oranges.

Let’s do some math.

The CapeFlyer runs 15 to 16 (16 in 2015) weekends a year, plus extra runs on Memorial Day, July 4 (sometimes) and Labor Day. That’s a total of 47 to 51 days—let’s say 50 for the roundness of the number. The distance from Boston to Hyannis is 79.2 miles (about 80), and it makes a round trip each day, so the total distance traveled is about 8000 miles. The operating costs are about $180,000, yielding an overall operating cost of $22.50 per train mile (or about $750 per train hour; note also that a Northern New England Intercity Rail Initiative report had very similar operating costs for a five-car Commuter Rail consist: $22.97 per train mile or $793 per train hour). Just the cost of the crew’s hourly wages and fuel adds up to about $150,000 [1]. If you ignore all the other costs of running the railroad (capital costs and depreciation, vehicle maintenance, maintenance facilities, stations, signals, crew benefits, maintenance of way, overhead costs, etc.) then, yes, the CapeFlyer makes a profit.

But what are the actual costs? According to the National Transit Database, in 2013, the T’s commuter rail operated at a cost of $15.92 per vehicle revenue mile. Not train revenue mile. Vehicle revenue mile. The Cape Flyer is generally made up of nine vehicles: eight coaches and an engine (often two for redundancy; a rescue train would be hours away from Hyannis). So the actual cost of the CapeFlyer is $15.92 times 9: $143 per mile. That’s more than six times the direct marginal operational costs which are used to show the “profit” that the train apparently turns.

If the CapeFlyer had to cover all of the fixed costs as well as the marginal ones, it would be bleeding red ink, just like weekend Commuter Rail service.

And there’s the rub. The MBTA Control Board wants to nix MBTA Commuter Rail service, because they ascribe to that service the full costs of running the trains, while pointing to the CapeFlyer as an example of a “profitable” service when it comes nowhere near to covering the costs that weekend Commuter Rail is asked to cover. It is not a fair or principled comparison.

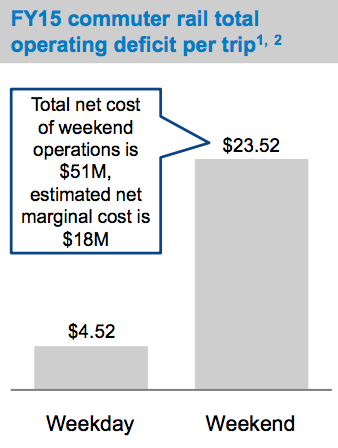

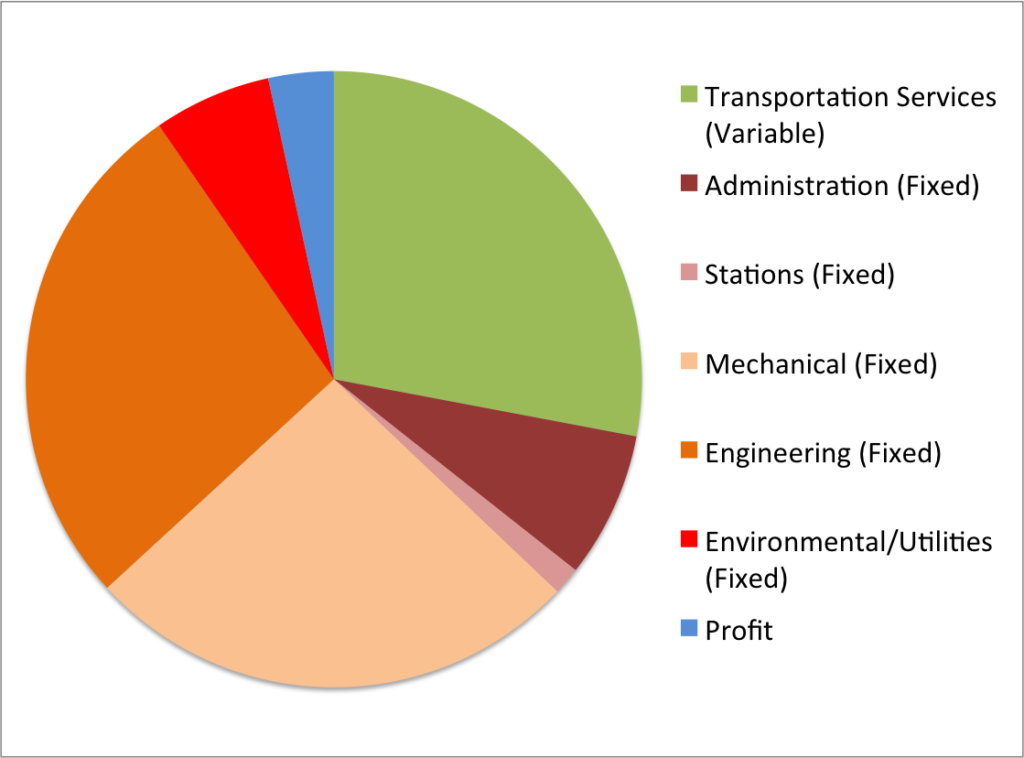

Most of the costs in running weekend Commuter Rail are fixed. The Control Board even admits this (see the screenshot from their report to the right). We already have the trains. We already have the stations. And the track, and the signals, and the crew benefits and all else. According to the Control Board documents, the average weekend subsidy per ride is $23.52. Assuming the average fare paid is in the $6 range, fares cover only 20% of the costs of running the trains on the weekends (overall, fares pay about 50% of the cost of Commuter Rail). But let’s assume that weekend Commuter Rail trains are accounted for at the rate of the CapeFlyer: $22.50 per train mile [2]. If we only count those costs, the total cost per passenger drops from $29.52 to between $4.52 and $10.33 [3]. That’s a lot less than $30, and in some cases, less then the average fare. So, using the same “innovations” that the CapeFlyer uses to turn a profit, weekend Commuter Rail service might well be able to turn a profit, too. Even if you assume that weekend service would use shorter trains (and therefore cost less) it would certainly require less than a $30 subsidy for each passenger. [4]

By not accounting for the fixed costs, CapeFlyer appears three to seven times cheaper to operate than regular Commuter Rail service. But perhaps instead of using these numbers to kill weekend Commuter Rail, we should use them to enhance it. If the CapeFlyer can show a profit at an operating cost of $22.50 per train mile, better Commuter Rail service on other lines likely could as well. Right now, with high fares and infrequent, inconvenient service (on some lines, only once every three hours!), weekend Commuter Rail ridership is low. What if we had hourly service (and perhaps lower off-peak fares) to and from Gateway Cities like Lowell, Worcester, Lawrence and Brockton? What about convenient, hourly service from Providence to Boston (which is generally faster than driving), with tourist attractions at either end of the line. And certainly hourly service to the beaches on the Newburyport and Rockport lines; lines which often fill trains in the summertime, despite the anemic current schedule.

We already pay for the track, the stations, the signals and myriad fixed overhead costs. The marginal cost of running the trains themselves—as the CapeFlyer shows—is relatively low. If we apply the accounting “innovation” of the CapeFlyer to weekend Commuter Rail service, it would be an argument to run more service, not less. If we’re going to uphold the costs of Commuter Rail with the CapeFlyer, perhaps we should try that.

A note before the footnote calculations:

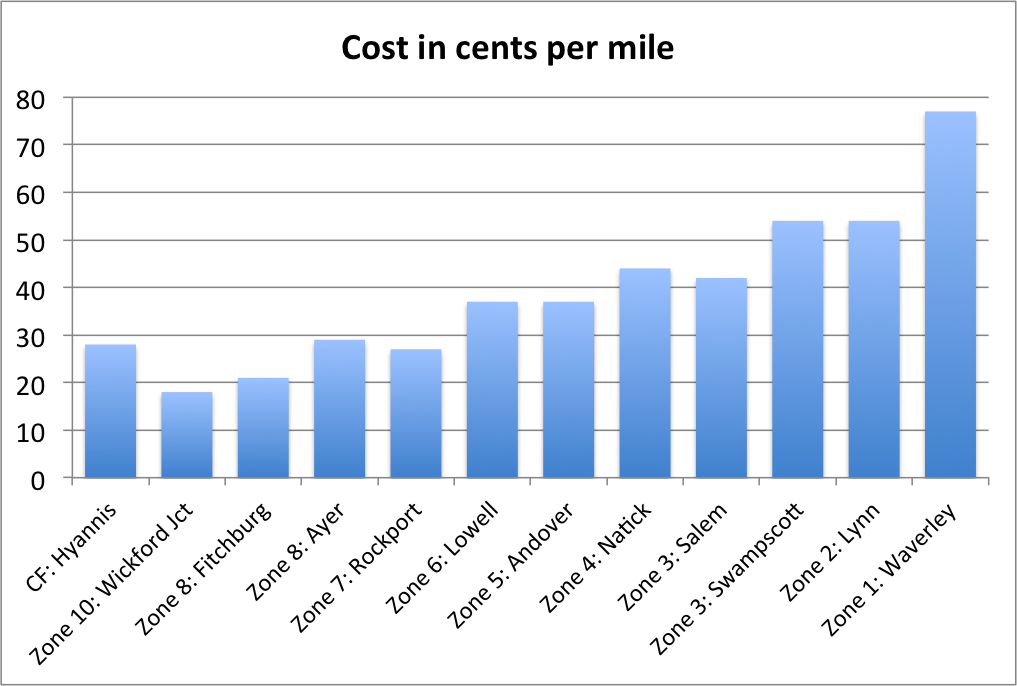

While CapeFlyer has a higher fare than any other Commuter Rail service, it is not really a “premium service.” The $22 fare for 79.2 miles works out to 28¢ per mile (cpm). For comparison, the 49.5 mile trip from Fitchburg to Boston costs 10.50 (21 cpm), but shorter trips cost a lot more—some coming in at double the cost per mile of the Cape Flyer. So higher fares do not come anywhere close to account for the difference between the “profitable” CapeFlyer and other services. There are savings available for monthly pass-holders, but this is only in the range of about 20%. Even with these discounts, any trip inside Zone 6—approximately I-495—is more expensive than the CapeFlyer.

|

|

|

| From Keolis bid documents. 3/4 of the cost categories are fixed costs. As is some of the fourth. |

[1] This assumes 4 crew members for 8 hours including report time and layover time per day, 50 days of operation. $43/hr for an engineer, $35 for a conductor, $34 for each of two Assistant Conductors. Total direct wages of $58,476. See page 10 here for exact numbers, and note that there are a lot of other staff listed there beyond these which are not included in the calculation (nor are benefits, which account for an additional 40% of pay, but are fixed costs). A Commuter Rail train uses approximately 3 gallons of diesel per mile of operation, so 8000 train miles per year use about 24,000 gallons of diesel. Diesel prices have ranged in the past three years from $2.50 to $4 per gallon, for a cost of $60,000 to $96,000. Thus, the total crew and fuel costs range from about $120,000 to about $160,000.

[2] And, no, comparing hourly costs does not make this any different: the CapeFlyer and regular weekend Commuter Rail service both average about 35 mph.

[3] $4.52 if you compare a nine-car train like the CapeFlyer, $7.67 for a five-car train, and $10.33 according to the Control Boards own documents comparing the net marginal costs and the total costs. In theory the T should only be reporting costs for open cars during operation, but that doesn’t seem to be the case.

[4] Let’s look at this another way. A train from Boston to Worcester runs 44.5 miles. At $22.50 per hour, that means it’s direct CapeFlyer-accounting costs is almost exactly $1000. If the cost per passenger is actually $30, it would mean that only 33 people were on the average weekend train. I have taken the Worcester weekend service many times, including the (at the time) 7:00 a.m. outbound train. And there were quite a few more than 33 people on the early train outbound from Boston (more than I expected). The average weekend train carries about 100 passengers per train according to the report’s numbers, closer to 150 per train according to the T’s data (although ridership has dropped in recent years, perhaps owing to more elasticity on weekends when the train is less convenient and parking costs are lower). For what it’s worth, a CapeFlyer train only carries, on average, 130 passengers.

Finally, the T pays Keolis $337 million each year to run Commuter Rail on average—$308 million in 2015—and trains run approximately 4 million miles per year and 22 million coach miles per year. This works out to an average train length of 5.5 cars (about right), a cost per coach mile of $15 (about right) and a total cost of $84 per train mile—about four times what the “profitable” CapeFlyer costs, and that’s at the low end of the estimates.