I’m digesting the study from Boston BRT from the ITDP group (second installment on the actual capacity of BRT here) and while I certainly appreciate forward-thinking planning in transit, I feel that they are selling us a bill of goods in several respects. One is promising that Boston can cheaply and easily have a “Gold Level” bus rapid transit, a level attained only by a handful of South American cities. The problem is that Boston’s street geometry and grid does not allow for that level of service, even by the ITDP’s own scorecard. We shouldn’t marry ourselves to an artificial and unattainable standard, but we should build the transit system that we need.

The scorecard is out of 100 points, and you need 85 to meet the gold standard.

Here are the Boston BRT’s routes, and their highest possible scores (within reason, anyway) based on the detailed ITDP scorecard (sorry for the janky Blogspot table format):

| Criteria | Points | Blue Hill Ave | Dudley-Downtown | Hyde Park Ave | Dudley-Harvard | Dudley-Sullivan | Notes |

| Dedicated Busway | 8 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | Assumes separated lanes for 75% of BHA, and colorized/exclusive lanes for 75% of other corridors. |

| Busway Alignment | 8 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | Assumes an average of 5 points for corridors other than BHA. |

| Intersection treatments | 7 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Will be hard to ban turns across busway outside of Blue Hill Ave corridor. Assume some turns prohibited and signal priority. |

| Multiple Routes | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 | No other buses use Hyde Park Ave |

| Demand Profile | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | Highly dependent on high-demand areas, which are often the most space-constrained. |

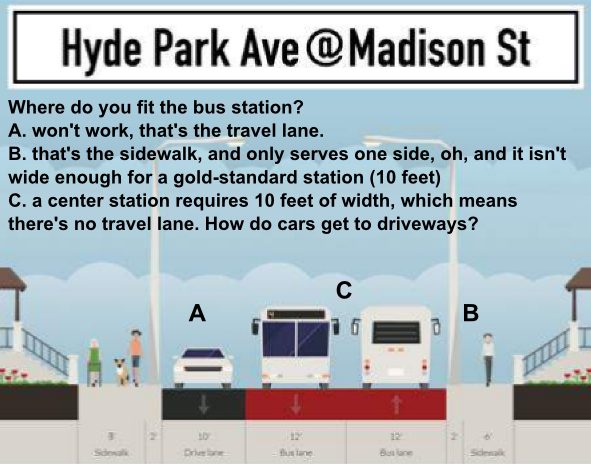

| Center Stations | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Center stations + lanes require 32 feet of width. |

| Station Quality | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 foot required width unlikely at all stations in narrower corridors. |

| Pedestrian Access | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Requirement of 10 foot sidewalks rare in Boston. |

| Bicycle Parking | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Standard of bike racks in most stations unlikely. |

| Bicycle Lanes | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Some bike lanes qualify for one point. |

| Bicycle Sharing | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Requires bike sharing at 50% of stations. |

| Systemwide | 55 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | See Below |

| Total | 8 | 82 | 73 | 65 | 70 | 70 |

Systemwide points assumes that Boston could qualify for full marks in a variety of categories, i.e. there are no physical constraints: operating hours (2), comtrol center (3), platform level boarding (7, although this may be difficult on downtown corridors), top-ten corridors (2), multiple corridors (2), emissions (3), intersection setback (3, assuming exceptions for frequent short blocks), pavement quality (2, although whether a 30-year pavement is attainable in New England’s climate is unknown), station distance (2), 2+ doors (3), branding (3), passenger information (2), accessibility (3), system integration (3).

Systemwide points where Boston would not qualify for full marks: fare collection (7/8, assumes full proof-of-payment system; otherwise it requires turnstiles at each station), express-local service (0/3, requires passing lanes), passing lanes (0/4, requires wider streets), docking bays (0/1, requires passing lanes).

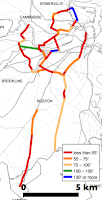

- 130 feet or wider. This is the majority of street widths in Bogotá.

- 100 – 130 feet. This is the minimum width in Bogotá except for two short portions: a narrow portion to a terminal downtown on a bus-only street (which is still 50 feet wide at its narrowest) and the southern portion, which runs non-stop through an undeveloped area to a terminal station. This is generally the minimum for passing lanes at stations.

- 75 – 100 feet. This is the minimum width of most streets in the Mexico City network. Few Boston streets are even this wide. This generally permits single-lane stations, but not stations with passing lanes. This is the bare minimum width for a “Gold Level” BRT (although Mexico’s system is rated “silver”.

- 55 – 75 feet. This is the minimum width of any BRT line in Mexico City. This is the minimum width for a complete street with two lanes of BRT, a station and either two lanes of traffic or one lane of traffic and bicycling facilities.

- Less than 55 feet. There is no way to fit BRT on a street this wide without removing all but one lane of traffic. While BRT can run on streets of this width, they have to be in areas which do not require any auto access, and nearby streets need to be able to host adequate bicycling facilities. In a city like Boston without any street grid, this is impossible to provide. There might be a it of fungibility at the high end of this scale—something like the 53-foot-wide Harvard Bridge which could have a bus lane, a travel lane and a bike lane on each side, barely—but only in areas that don’t require any stations, at which point it’s just too narrow.

In the ITDP’s 25 page report, here’s what they say about street geometry:

Boston has a unique cityscape, and while the ITDP analysis shows that

Gold Standard is possible, there are stretches where routing would pose a challenge. For

example, tight passages can still accommodate BRT, but in some cases a street may need

to be made BRT-only, or converted to one-way traffic.

They also admit that it might be a wee bit harder to fit “gold standard” in Boston:

It’s important to note that all of these travel time projections

are based on implementing BRT at the gold standard throughout the entire length of the corridor. This study acknowledges that achieving every

element of Gold Standard in a few portions of some of the

corridors would require some bold steps. The exact corridor

routing and any associated trade-offs will have to be explored in

more detailed analyses in the future.

Yet their travel time savings analyses (appendix C, here) assume median bus lanes, which they state aren’t possible. This is—ahem—a lie. From Dudley to Harvard most of their savings come from congestion reduction:

Median-aligned dedicated BRT infrastructure

will greatly reduce the 20.6 minute delay associated

with congestion.

Yet most of this corridor is too narrow to support median bus lanes and stations. (Not to mention that by analyzing the 66 they choose the longest possible Dudley-to-Harvard route—the 1, CT1 or Silver-to-Red Lines are all faster—and 66 bus schedules to Harvard include schedule padding for the loop through Harvard Square.) Yes, in theory, most of the corridor could have such lanes, but only if a single lane were left for vehicles, driveway access and loading, to say nothing of bicyclists. That’s just not going to happen, especially on that route through Brookline.

So, they acknowledge that street width might be an issue (read: probably impossible), but that’s something to be studied in the future, but the numbers assume that it’s a done deal. (More studies! More money for the ITDP!) This is intellectually dishonest. If something isn’t going to work, it should probably inform your study. This would be be like if someone studied a high speed rail line and said “do note that because we can’t plow straight through a major metropolis, the exact corridor routing might be slightly longer than analyzed” but then analyzed the straight line distance anyway.

Look at the maps above. Street width is a slightly bigger problem than they make it out to be. It comes down to the fact that the highest performing bus rapid transit lines are built in cities which already have a lot of room to work with. Boston is much less like South America or Asia (newer cities with wide roads) and much more like Europe (older cities with more constrained rights of way). There are not many ITDP busways in Europe.

More to come on such topics as where we should have BRT in Boston, how we should go about implementing it, and what we should implement in corridors where BRT is not workable. But suffice to say, we should not paint ourselves in to a corner by adhering to an arbitrary standard like the one from the ITDP.

I don't like the ITDP standards sometimes because a lot of what they think is "Gold Standard" is also anti-urban. Bogota's BRT line might as well be a freeway in some parts with how it integrates into the urban environment.

Very good point. A 110 foot wide street takes more than 30 seconds to cross for an average walker, to say nothing of an elderly or mobility-impared person. A 150 foot wide street takes nearly a minute. This sort of BRT only works when you have barriers in the middle of wide streets, making pedestrian travel much harder. Light rail can attain the same capacity with a much narrower, more walkable street (see my next post, or Calgary: 20,000 passengers per hour in a <40-foot-wide street). Bogota's BRT line is basically in a freeway. Light rail can interact with the urban environment while still having high throughput, as can anything underground (and at some point, it makes sense to bite the bullet and put transit underground). Bogotá happened to have a bunch of very, very wide roads for their transit system. Without those, you never get the capacity. But with them, you have a fragmented urban fabric.

The thing is, we've already built the most important, tricky, and expensive parts, on the narrowest and most congested streets. In fact, Boston has the foresight to do that almost 120 years ago with the Tremont St Subway, which still has spare capacity for services coming from the direction of the old Pleasant St. Portal.

Also, light rail has some hard geometric advantages on narrow streets, even disregarding the issue of capacity: the trains don't need to steer, so tracks can be spaces somewhat closer than lanes. And since trains are on rails, the back of the train follows the same curve radius as the front, unlike buses where the rear wheels follow a smaller turn than the front, and so require big sweeping spaces to make sharp turns, which results in 20 foot wide slip ramps that are annoying and dangerous for pedestrians (just look at the geometry around Silver Line Way).