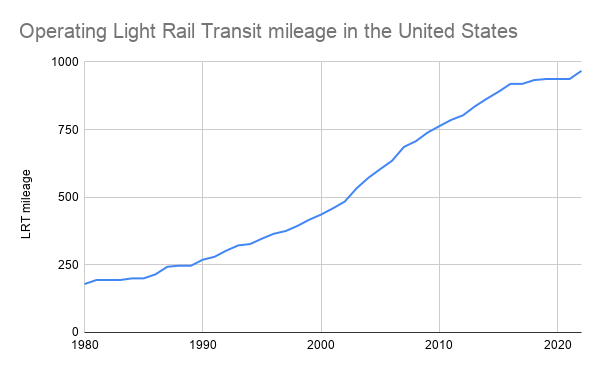

In 1980, there were about 175 miles of what could be considered streetcar or light rail operating in the United States. This was based entirely in about half a dozen “legacy” systems which were never converted to buses (a few miles have been converted to buses since then, this figure does not include streetcars abandoned after 1980), in general because they used private rights-of-way and, in most cases, tunnels in:

- Boston

- San Francisco

- Philadelphia

- Pittsburgh

- New Orleans

- Cleveland

- Newark

There had been minimal expansion since the 1930s (most notable: the MBTA’s 1959 Highland Branch) and the systems mostly used PCC cars (or older streetcars in the case of New Orleans). The ill-fated Boeing LRV cars were only first being introduced in the late-1970s.

Over the next 35 years, light rail and streetcar mileage increased by a factor of five. This began with 100 miles in the 1980s, accelerated further in the 1990s, and further more from 2002 to 2016, with 30 miles per year being added per year from 2002 to 2012, and additional increases through 2016.

In 2016, however, LRT implementations stalled out. Funding protocols had changed, and in several cases, expensive light rail systems had been built in areas with marginal supporting land use, leading to stagnant or declining ridership in some areas. “Modern streetcars”, which do not add up to much mileage but had been some of the least cost-effective projects, had mostly fallen out of favor. 2017 marked the first year since 1989 with no new LRT mileage opening, and only 18 miles of new light rail have opened since (2020 was another year without any new mileage).

This will change in 2021 and 2022, when, over the course of a few months, five large light rail projects set to come online:

- LA’s K Line (Crenshaw)

- San Francisco’s Central Subway

- Boston’s Green Line Extension (in Cambridge, Somerville and Medford)

- San Diego’s Midcoast Trolley

- Seattle’s Northgate Link

What is notable is that these are already some of the largest and most effective light rail systems. By total ridership, they rank, respectively, 1, 2, 3, 5, and 10, and by ridership per mile, they rank (again, respectively) 10, 2, 1, 12, and 3. Together, these projects will add 30 miles of light rail service, but they are not what we saw a lot of in the 2000s, with often suburban extensions with low ridership. In each case, the new portion will have a higher ridership density than the existing system did pre-pandemic)

- K Line: 4050 (system: 2517)

- Central Subway: 42941 (4479)

- GLX: 10465 (system 7846)

- Midcoast Trolley: 3154 (system 2157)

- Northgate 5116 (system 3728)

These are really LINO projects, or LRT-in-name-only. (Or maybe LIVO; LRT in vehicle only.) The projected ridership would fall in the range of many existing heavy rail systems, and with the exception of the K Line in LA and the first few hundred yards of the Central Subway before the portal, there are no street grade crossings for any of these projects. They will all use two- three- or four-car trains to provide as much capacity as subway systems, just with light rail cars, providing travelers with frequent service at speeds which, during peak hours, are faster than driving.

If LIVO is the direction that light rail is headed, it is indeed a good one. Some earlier light rail systems are streetcar-light rail hybrid systems which can be stymied by surface congestion, or followed highway rights-of-way or relatively remote rail line corridors which reduced ridership potential. These decisions are often made in the name of reducing capital costs, but result in increased operating cost per rider. No one would accuse any of these five new projects of being built on the cheap: each checks in at well over $1 billion, with several miles of tunnel (in the case of Seattle and San Francisco, most of the project is tunneled) or viaduct. All should probably be less expensive per mile, but assuming travel patterns return to near some pre-covid normal, all should have high ridership.

In essence, they do what light rail can do best: fit a high-capacity transit system into an urban ecosystem where it something beyond the capacity of a busway is needed*, but where heavy rail or commuter rail would not be feasible. San Francisco’s Central Subway is a subway with a surface station and connection to existing transit lines. Seattle’s Link system is a mostly-elevated, sometimes-tunneled, and sometimes at-grade system (although after the initial segment, they seem to be moving away from at-grade portions). Los Angeles combines tunnels and at-grade segments, and San Diego’s is an extension of an at-grade system with grade crossings. Boston’s system mostly follows existing Commuter Rail lines and could have been built on those lines’ existing alignments, however to do so would have required completion of the North South Rail Link. Light rail, on the other hand, can allow existing vehicles to run through the city, rather than terminating and turning back at several congested 19th- and early 20th-Century Downtown terminals, which will serve to improve service across the entire line.

(* A note on busways: while most any of these projects could have been built as a BRT, all would have significant downsides. Once a project is nearly entirely grade-separated, the construction cost differential for BRT dissipates. BRT also has two major issues operating in tunnels. One is ventilation: without full electrification, buses require exhaust for diesel power. Buses also need more roadway width to operate, while rail can be fit into a more constrained environment. Buses also have lower per-vehicle capacity than rail, leading to higher labor and operating costs per passenger. Given the high ridership density for these routes, BRT would not likely be the appropriate mode.)

Light rail will probably not again see the kind of growth it did from 1990 to 2016. Some of these systems which are mostly at-grade and have lower ridership potential would have done better as bus rapid transit, such as Sacramento, San Jose, or Houston. Others, like Denver and Dallas’s sprawling systems mostly along rail rights-of-way, would be better suited for Commuter or Regional Rail, and indeed both these cities have shifted towards this mode. With the promise of new funding, light rail implementations will hopefully hew closer to the recent implementations than the “every city gets a light rail whether they need it or not” service of the 1990s and early 2000s.

Light rail is a bit of a chameleon. Depending on its situation, it can act as a streetcar, heavy rail, commuter rail or even something akin to a BRT, and can take on both the positive and negative qualities of each of these modes. It does best when it serves a corridor which would otherwise not be well-serviced by any single mode, and where it can provide high-speed, high-capacity, high-frequency service while shape-shifting as it moves through the urban environment.