I’m tired of going to public meetings. Especially meetings organized by businesses in Cambridge where they accuse bicycle advocates of top-down planning which is making the roads unsafe, open the meeting by saying they don’t care about data (“then why are we here?”) and close by saying the want to collect anecdotes. They go on to complain that there has been no public process (which is interesting, given I’ve been part of a lot of this process) and say that the facilities are unsafe because they think they look unsafe. Let’s look at some of their “arguments” and break them down, and then let’s give the public some talking points for pushing back at subsequent meetings.

1. Don’t let “them” set the meeting agenda. If a meeting is billed as a “community” meeting, it should be led by the community. If the businesses are taking charge, before the start the meeting, go up to the dais and propose the following: that the meeting be led by a combination of the community members and the business association. Have a volunteer ready to go. If they refuse, propose a vote: let the people in attendance vote on the moderator. If they still refuse, walk out. (This obviously doesn’t go for city-led meetings, but for these sham public meetings put on by the business community which are only attended by cyclists if we catch it.)

2. Ask them about business decline data. I don’t believe they have it. They claim that business is down because of the bike lanes, but ask by how much, and how many businesses. There is very likely a response bias here. Which businesses are going to complain to the business community about sales being down? The ones with sales which have gone down. Better yet, come armed with data, or at least anecdotes. Go and ask some businesses if their sales have been harmed by the bike lanes. Find ones which have not. Cite those.

3. There has been plenty of public process. The anti-bike people claim that there has been no public process, and that the bike lanes have been a “top-down” process. These arguments are disingenuous, at best. The Cambridge Bicycle Plan was the subject of dozens of meetings and thousands of comments. If residents and businesses didn’t know it was occurring, they weren’t paying attention. It would also do them some good to come to the monthly Bicycle Advisory Committee meetings, where much of this is discussed (they’re open to the public; and committee members take a training on public meeting law to make sure procedures are carried out correctly). These are monthly, advertised meetings. If you don’t show up, don’t complain about the outcome.

Then there’s participatory budgeting. The bike lanes on Cambridge and Brattle streets rose directly from participatory budgeting. This was proposed by a citizen, promoted by citizens, vetted by a citizen committee and voted on by citizens. Yet because the Harvard Square Business Association didn’t get a voice (or a veto), it was “top down.” They’d propose a process where they dictate the process, which is somehow “grassroots.” This is untrue. Don’t let them get away with this nonsense. The bike lanes are there because of grassroots community activism. If they don’t like them, they had their chance to vote. They lost.

4. Bike lanes cause accidents. After the meeting, a concerned citizen (a.k.a. Skendarian plant) took me aside to tell me a story about how the bike lanes caused an accident. I didn’t know what to expect, but they told me that the heard from Skendarian that a person parked their car and opened their door and a passing car hit the door. I was dumbfounded. I asked how the bike lane caused the accident and was told the bike lane made the road too narrow. He liked the old bike lanes, so he could open his door in to the bike lane. So if you hear this story, remember, this was caused by a car hitting a car. And if someone says that bike lanes require them to jaywalk to reach the sidewalk, remind them that 720 CMR 9.09(4)(e) says that a person exiting a car should move to the nearest curb, so crossing the bike lane would be allowable.

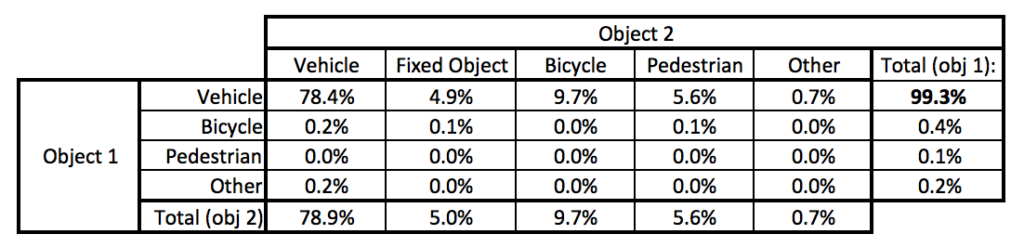

5. Data. The anti-bike forces will claim they don’t want to use data. There’s a reason: the data do not work in their favor. They may claim that the data don’t exist. This is wrong. The Cambridge Police Department has more than six years of crash data available for download, coded by location and causation; the Bicycle Master Plan has analyzed his to find the most dangerous locations. Who causes crashes? More than 99 times out of 100: cars. (Note: object 1 is generally the object assumed to be at fault.)

When I dowloaded these data last year, there were 9178 crashes in the database. If someone mentions how dangerous bicyclists hitting pedestrians is, note that in six years, there have been five instances where a cyclist caused a crash with a pedestrian. (This shows up as 0.1% here, it’s rounded up from 0.05%. Should this number be less? Certainly. But let’s focus on the problem.). There have been 100 times as many vehicles driving in to fixed objects as there have been cyclists hitting pedestrians. Maybe we should ban sign posts and telephone poles.

—

I’ve written before about rhetoric, and it’s important to think before you speak at these sorts of meetings (and, no, I’m not great about this). Stay calm. State your points. No ad hominem (unless someone is really asking for it, i.e. if you’re going after the person who says they don’t care about bicycle deaths, yeah, mention that). Also, don’t clap. Don’t boo. Be quiet and respectful, and respect that other people may have opinions, however wrong they may be. When it comes your turn, state who you are and where you live, but not how long you have or haven’t lived there. When they go low, go high. We’re winning. We can afford to.

Ari, don't sell yourself short in thinking before speaking. I wish you would have spoken up more at public meetings that I attended.

Also, awesome post.

Better to be thought a fool …

But more to the point: Never write if you can speak; never speak if you can nod; never nod if you can wink.

Did you try adjusting those stats per capita? It's very easy to dismiss that data by saying "well of course cars cause more crashes there are more of them on the road!"

Per capita or per mile traveled stats might be useful in deciding whether to encourage switching from one mode to another but not if your goal is to implement safety improvements to reduce the overall rate of traffic incidents, in which case you'd definitely want to focus on the actual overall rate. Besides, even if you do get the rates per-capita (or per-mile) I don't think there are actually 100 times more cars in Cambridge than bikes. Well, maybe by cubic feet of space taken up but not otherwise.